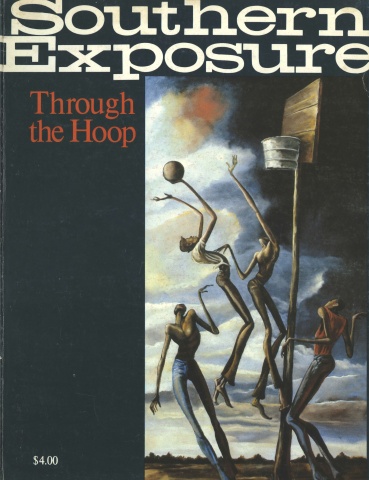

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

The tarnished trophies, proudly hung photographs and sparkling eyes — still excited more than 25 years later — all tell the same story.

“Eckie and I would have gone to the moon to play in a basketball game.”

“Sure we would.”

As it happened, Eunies “Eunie” Futch and Evelyn “Eckie” Jordan went to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in the late 1940s to play basketball for the Hanes “Hosiery Girls.” Before they were through, Jordan had become a five-time All-American and Futch had won the same honor three times. The rules, and the rewards, have changed since Hanes Hosiery, the last of the great industrial women’s basketball teams, won three straight national championships and ran up an incredible 102-game winning streak. Women are allowed to dribble more than once now, to win scholarships and to play in the Olympics. But few have ever wanted to play more, or been better at it, than the women who “ate, slept and drank” basketball while working for Hanes Mills after World War II.

High caliber women’s basketball in the South wasn’t born in the 1970s; it merely got its second wind.

Eckie Jordan grew up in Pelzer, South Carolina, during the Depression and learned to play basketball because her father and brothers and sisters played. Pelzer was a cotton mill town, which like many other mill towns in North and South Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee, boasted outstanding men’s and women’s basketball teams competing in the Southern Textile League.

“You were bred and grew up teething a basketball in that area back then,” she says. “We lived at the gym.” Eckie remembers clearly that girls received the same encouragement, and financial support, as boys did.

After helping her high school team win the state championship, Eckie went to work in the local mill, playing basketball intermittently during the war years. After World War II, she was recruited by the Chatham Blanketeers of Elkin, North Carolina, a leading textile team. But Eckie had seen Hanes play at cavernous Textile Hall in Greenville, South Carolina, the site of yearly tournaments for both sexes, and went to try out for Hanes instead in 1948. She had been engaged to a sailor who had “jilted” her after the war, and she was ready to go on to “bigger things.”

At 5’2 1/2”, Eckie is short for a basketball player. So the Hanes coach, Virgil Yow, told her that there was no way she could make the team. She would, of course, prove him wrong. She became his quarterback, his playmaker, controlling the tempo of the Hanes women’s team on the way to their championships. “He lived to eat his words,” Eckie says.

When Eckie walked into the Hanes gym intent on proving herself, the First person she saw was Eunie Futch, who at 6’2 1/2” tall — exactly a foot taller than she — stopped her dead in her tracks. She recalls saying to herself, “Lord have mercy on my soul, that’s the tallest girl I’ve seen in my life.”

Eunie had come to Winston-Salem from Florida, where she grew up playing basketball on Jacksonville’s playgrounds. “Basketball was just with me from the beginning,” she says. “I can remember going to that playground when I was in elementary school and could not get the basketball in the goal. That was my life’s ambition.”

Always the tallest in her class, Eunie played mostly with the boys and found herself wishing she were a boy so she could compete with them on organized teams. There were no basketball teams for women in Florida’s high schools. After seeing her play for an independent team in Florida, however, Coach Yow asked her to come play for the Hosiery Girls after she graduated from high school in 1947.

The offer allowed her to play basketball and work steadily, so she accepted. “Back then you just jumped at a job,” she recalls, “and not too many women went to college. To play basketball and work was the treat of all treats.”

Duties at the mill were combined with a rigorous- practice and game schedule for the dozen team members. They played about 30 games between Thanksgiving and the end of March. The women worked regular shifts except when traveling for games and were paid straight time for the work days they missed. The company assigned them to different areas of the plant so that no one function would be affected too greatly during their absence. Coach Yow insisted that they were not to miss their regular shifts at any other times, even if the team had returned from a trip at three a.m. the previous morning.

Practices were tough. Yow coached the Hanes men’s team as well as the women’s, and Eckie recalls that he “wanted us to be as tough as the boys.” The women would get off work about five p.m. and sometimes practice until nine p.m. “It didn’t bother us,” says Eunie. “It was what we came for.” Back then, she recalls, “Basketball was my life.”

Yow’s persistence, and the women’s desire, paid off in the team’s performance, especially at the free-throw line. His method for teaching shooting included an adjustable basket, which he would set up first at six feet and then move gradually up to 10 feet. His players would shoot at each level until they hit 1,000 shots, while Yow checked for form, spin and follow-through. The players kept records of 50-shot sequences, shooting as many as 10,000 times.

As a result, Hanes dominated the yearly national free-throw shooting contest, winning the title four straight years between 1948 and 1952. The 1952 champion, Hazel Starrett Phillips, won by making 47 of 50 attempts at the line. Unfortunately, no records of game percentages were kept, but it is noteworthy that in the newspaper box scores of Hanes’ games, the only other statistic kept besides points scored was free throws missed.

The game the Hanes women played, Eckie says, can’t be compared to the game women play today, which is virtually the same as the men’s game. The basic concepts of basketball have not changed since James Naismith first threw a soccer ball into a peach basket in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891, but basketball has taken many different forms, including the six-player version Eckie and Eunie played.

Scores were low compared to today, in part because the teams played only four eight-minute quarters (as opposed to two 20-minute halves now), and in part because the players’ mobility was quite limited. “It took forever to get the ball down the court,” Eunie explains, because players could dribble only once. Occasionally the women were allowed to let loose and play boy’s rules. “We went wild,” says Eunie.

“I would have given anything to play men’s rules. But the people over in Greensboro (professional educators) said it was too hard on us.”

Despite the handicaps women played under, their brand of basketball was very popular among the mill’s employees and the residents of Winston-Salem. The Hanes gym’s 2,000 seats were sold out each time they played, with employees paying 25 cents and outsiders 75 cents. When the team won its first national championship in the Midwest, the players received more than 300 telegrams from plant employees.

At Hanes, just as in Eckie’s hometown, basketball was “a community project.” Eunie believes, “It was good for morale. It gave everybody in the company something to talk about and look forward to. . . . Back then, that was the thing to do — to go watch the Hanes Hosiery boys and girls play.” Eunie also reasons that the timing was right for basketball to be a popular leisure activity; television sets and cars were not widely owned among mill employees.

It goes without saying that the Hosiery Girls also received the unqualified support of the Hanes management during their heyday. The company built a new gym in 1940, paid all the team’s expenses, and provided a chaperone, a business manager and a nurse (often Mrs. J. N. Weeks, wife of the company president) to assist with the women’s program. “Mr. Hanes and Mr. Weeks,” says Eckie, “did it because they loved the sport and the people.”

The team brought favorable press attention to Hanes Industries, receiving praise from both the local press and industrial publications. A column in the loyal local paper referred to President Weeks by saying, “Every community needs more men like Jim Weeks and his associates at Hanes to make it a worthwhile place in which to live.” Thus, whether intended or not, industrial sports in Winston-Salem, as in countless other factory towns, became a crucial bridge between workers and management, between company and community.

By 1947, after competing for many years in the Southern Textile League, the Hanes women’s team was testing itself against national competition regularly and taking part in the only annual national playoff for women, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) tournament. The AAU had held a title tournament for women every year since 1926, with independent, industrial and college teams participating. (Not until 1972, when the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women [AIAW] organized a second championship for women, would the colleges have a national playoff of their own.)

The Hosiery Girls did not “fast break” their way to the top of the women’s basketball world; it was a slow process as they inched their way closer to the time when the Winston-Salem newspapers would call their city the “New Women’s Cage Capitol.” The team improved its showing in the AAU tournament gradually from 1947 to 1950. At first, they came away empty-handed, unless you count the bouquet of roses presented to Cornelia Lineberry when she was named Tournament Queen in 1947. A year later in St. Joseph, Missouri, with Lineberry’s picture featured prominently in the red, white and blue official program, the Winston-Salem club did better, losing in the quarter-finals to a team representing Nashville Business College (see sidebar). It is notable that while the 32 competing teams in 1948 were from all parts of the country (including Milwaukee, Wisconsin, East Chicago, Indiana, and Acworth, New Hampshire) six of the eight quarter-finalists were teams from North Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee — signaling the dominance by Southern teams which would continue through the 1950s and ’60s.

At the 1949 and 1950 tournaments, the Hanes women’s confidence and reputation grew, despite consecutive losses to Nashville Business College. They moved into the semi-finals each year, losing by a score of 29-21 to their nemesis from Nashville in 1949 and then only by a single point, 32-31, in 1950. The Hanes women, who were by then called the “Masked Marvels” (an AAU official had required the players to cover up the word hosiery on their uniforms to avoid the “practice of seeking cheap advertising”) won the consolation game both years, finishing third. Coaches and AAU officials made Jackie Swaim, a 6’ forward, Hanes’ first All-American in 1949, and in 1950, Eckie and Jimmie Maxine Vaughn received the same honor.

The next year, Eckie says, “we knew was our year.” And when the team beat the Bomberettes from Martin Aircraft in Baltimore, 42-31, to move into the semi-finals against Cook’s Beer’s Goldblumes of Nashville, Eckie recalls, “We were ready to make our charge.” For Eckie and Eunie, the game was the most memorable one in their entire basketball careers; they say they can still remember every minute of the excitement. “It was anybody’s ballgame,” Eckie says, but after a controversial play went Hanes’ way and the best player on Cook’s fouled out, the Hosiery Girls prevailed, 41-38.

For the First time ever, the Hanes women moved into the finals. Their opponents were the Flying Queens of Waylands College, one of the few schools which had already begun to stress women’s basketball and offer athletic scholarships, under the sponsorship of a wealthy Texas rancher named Claude Hutcherson. Wayland’s day, however, would come later; 1951 belonged soundly to Hanes by a score of 50-34. As usual, Eunie dominated with her defense and rebounding, assuring victory by holding Wayland star Marie Wales to only nine points.

Before the 1952 season, Hanes lost eight players, according to Mary Garber of the Winston-Salem Sentinel, because “they either got married or were already married and their husbands didn’t want them playing ball.” However, Coach Yow added several players, including five-time All-American Lurlyne Greer, formerly with Cook’s Goldblumes. The Arkansas native had starred for the Nashville team, which was losing its sponsorship, so she applied for a job at Hanes and, to no one’s surprise, was accepted.

In an item fit for the sports page or the business page, the local press reported triumphantly, “Greer has a deadly hook shot and a jumpshot that is hard to stop. So far she likes her job fine. She has a lot of nice things to say about the people in the mill. Says they are friendly, and have been mighty nice to her. Seems like it’s both ways because her foreman has told B. C. Hall, Hosiery athletic business manager, that he’ll take all the girls like Greer he can provide.”

The 1952 tournament was held in Wichita, Kansas, and the rebuilt Hanes team proved mightier than ever. They moved into the semi-finals with a 57-30 win over the Jackson, Mississippi, Magnolia Whips. Greer scored 35 points, a tournament record. (Her season high had been 41 points — on 16 of 22 field goals and nine for nine at the free-throw line.) The Hosiery women were too much for perennial powers from the corn belt; they rolled over Iowa Wesleyan, 61-25, and then coasted through the championship game against Davenport, Iowa, American Institute of Commerce, 49-23. Jordan, Futch, Greer and Sarah Parker of Hanes won All-American honors.

During the 1953 season, the Hanes women broke the AAU record for most consecutive wins by taking their 60th triumph in a row in February against the Kansas City Dons. A month later, at the AAU tourney, they won their third straight national title by beating Wayland once again, 36-28. Not since Tulsa Business College triumphed in 1934, 1935 and 1936 had a team won the championships three straight years. Eckie, Eunie and Lurlyne were again named All-Americans.

The 1953 victory marked a high point the Hanes women would not reach again. Coach Yow retired after the 1953 season, and though the new coach, Hugh Hampton, led the team to a successful 1954 season, the unbeaten string could not go on forever. The team lost to the Kansas City Dons by three points in the semi-finals of the 1954 tournament, breaking their remarkable streak at 102 games. Hanes held onto third place by beating the Denver Viners, and in a victory which augured the later rise of intercollegiate over industrial women’s basketball, Wayland College took the national title. Never again would the AAU champion be a team which required all the players to work for the sponsoring company.

The Wayland victory also intensified the team’s rivalry with Hanes. Wayland teams went on to win four national titles and to claim a 131-game winning streak. But later in 1954, playing men’s rules during the tryouts for the Pan-American Games, the Hanes women beat Wayland, 46-39. Since the loss was not counted in Wayland’s streak, any true Hanes fan still claims the longest win streak in women’s basketball for the Hosiery women. “We whipped em good, boy’s rules,” Eckie says.

Eckie, Eunie and Lurlyne Greer Mealhouse went on to play in the Pan-American Games in Mexico City that year, the first time women’s basketball was included in the international competition. Despite the fact that the South American teams played with a soccer-type ball, the U.S. team swept the Games undefeated.

For Eckie and Eunie, the sweet victory over Wayland and the trip to Mexico City marked the end of an era. The Hanes team disbanded after the 1954 season. Eunie had seen the end coming; she had taken a long look around at the AAU tournament, she remembers now, knowing it would probably be her last. “I could have bawled a river.”

Eckie, Eunie and other observers can only speculate about the reasons industrial basketball faded out. Hanes had dropped its men’s program in 1952, saying “the practice and travel required of players during the regular season interferes with the work schedule of those players holding supervisory positions with the company.” Eckie recalls that the women too had begun to catch some flak from other employees for missing work. The company was growing, and there were more workers who were not followers of the team. In addition, their principal booster, Mr. Weeks, had retired.

The Hanes women were the last of the area’s textile teams to throw in the towel. Mary Garber, a local sportswriter, argued that fan support had fallen off due to the disappearance of local rivals, such as perennial textile champions, the Chatham Blanketeers, who dropped their women’s program in 1949. “Several years ago,” she pointed out, “the balance of AAU basketball power was in the East. There were a number of fine teams in this section, the Atlanta Blues, Nashville, Chatham and others. But now the basketball interest has moved West.”

Changing attitudes likely played an equally important role in the shrinking opportunities for women. In 1953, when the Hanes team was at the peak of its reign, the North Carolina state legislature took action to stop the increasingly popular state high school tournament for girls. Responding to pressure from educators, and ignoring the pleas from the tournament’s organizer for “equal privileges for girls under their own rules,” the legislature restricted the girls’ teams to one playoff each year. The bill effectively eliminated the state tournament, since most high school teams played a local or county-level tournament. The loss of the state playoff as a proving ground for the best players affected not only the feeder system which had benefited Hanes and other industrial teams, but also affected the level of girls’ and women’s programs for years. Not until 1972 did North Carolina again start up its girls’ high school tournament.

As Rosie the Riveter of World War II and Korean War years returned to the kitchen during the mid-’50s, the prevailing philosophy of women’s physical education was again coming to stress, as it had in times past, the virtues of widespread participation over high-level skilled competition. This attitude usually was defended in professional journals with a combination of arguments regarding proper female conduct and the possible threat posed by competitive sports to a young woman’s physical and psychological health. Actually, it was based as much on the assumption that “ladies don’t sweat” as on genuine professional concerns about what would benefit the many, rather than the few talented competitors.

Eckie had played for Hanes for seven years, Eunie for eight, and along the way, Winston-Salem had come to seem like home to them. Like some of Yow’s other championship players, they stayed on at the mill, and at least four of them still work for Hanes. Eckie, now 53, works in distribution, and Eunie, 50, works in the corporate tax office. Though many of them married, or moved away, Eunie and Eckie never did and have shared an apartment for the last 25 years. People still walk up to them on the street and talk to them about the days when industrial basketball, as opposed to the Atlantic Coast Conference college ball, reigned in Winston-Salem.

Several Hanes players were able to take advantage of the gradual shift of women’s basketball away from Southern industries and into the colleges, using the transition to further their own educations. Lu Nell “Tex” Selle went to Wayland College in Plainview, Texas, and is now a missionary. Hazel Starrett Phillips attended nearby High Point College and presently coaches in Winston-Salem. At least one player — Lurlyne Greer Mealhouse — played professionally. Mealhouse moved back to her native Arkansas after the team disbanded, where she played for at least a year for Hazel Walker’s touring professional team, the Arkansas Travellers.

Coach Virgil Yow also continued to play a role in encouraging and improving women’s basketball throughout the region. He instituted a number of rules changes that were accepted by the AAU rules committee, making the women’s game faster. His camp, PLA-MOR in Windy Hill Beach, South Carolina, begun in 1951, was the first sports camp in the South or anywhere else to include women’s basketball. Yow is the only living person to be selected to the Helms Sports Hall of Fame for contributions to both men’s and women’s basketball.

Eckie and Eunie coached basketball for a couple of years in Winston-Salem’s recreational league, and both play other sports, such as golf and tennis. However, neither has played basketball on a competitive basis since the Hanes team disbanded. Now the recent revival of high-quality women’s basketball has awakened old memories and rekindled the desire to play once more. “I’m not a good spectator,” Eunie says. “I’d rather be playing.”

The two say that today’s young women are no better than they were 25 years ago, though the playing style is very different. They contend that previous rules forced more finesse and better passing. What has not changed is the dominance of the Southern teams. In the first eight years of the AIAW championship, Southern teams have taken the title four years and grabbed more than their share of the other spots in the tournament. In a move that knits together the distant but related parts of women’s basketball history, Hanes now sponsors a special game for All-Americans called the Hanes Underalls Classic. Hanes officials enlisted Eunie’s and Eckie’s help to promote and organize the game, and the two women have been involved with the undertaking since it was conceived three years ago.

Eckie and Eunie stopped playing before many of today’s generation of players were born, so it is only natural that the new stars like to refer to themselves as the generation who broke the ice for women’s basketball. They are often surprised to meet and to talk to Eckie and Eunie, who by all rights should have been their role models. “I didn’t know they grew em that tall back then,” one young player recently said to Eunie.

That tall, or that good.

Tags

Elva Bishop

Elva Bishop is an alumna of Camp PLA-MOR and competes today in the Carrboro, NC, basketball and softball city leagues. She is finishing a masters in Physical Education at the University of North Carolina. (1979)

Katherine Fulton

Katherine Fulton, now a reporter with the Greensboro Record, is the former captain of the Harvard University women’s basketball team. (1979)