This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 2, "Just Schools: A Special Report Commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the Brown Decision." Find more from that issue here.

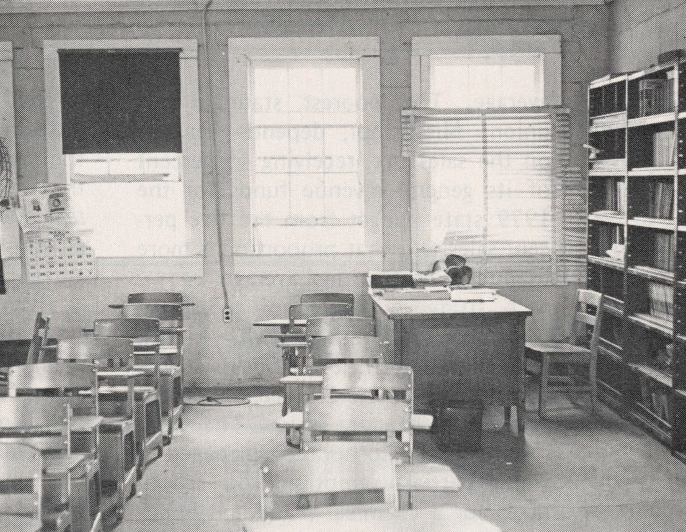

School children, teachers and administrators in the Maxton, North Carolina school district are demoralized by low achievement test scores. The district cannot afford to supplement the state salaries of its teachers, and the superintendent is desperately seeking funds to keep the school buildings from falling apart.

A South Carolina superintendent tries to repair the school buildings with his own hands. There is no money for buildings maintenance in the district’s coffers.

A Florida parent complains about the $8 she has to provide each year for her daughter’s school supplies. Out of their own salaries, teachers come up with supplies for children who cannot pay the fee.

In Noxubee County, Mississippi, teachers wait all year for requisitioned equipment that never arrives.

These people—and dozens like them in other Southern school districts—live daily with the inadequacies of school finance systems in the South. Evidence abounds that the education of blacks and other minorities is suffering from what is, in many cases, a deliberate scheme of under-funding in school districts where whites are in the minority. The inequities of these finance systems are receiving increasingly wide attention, stemming in part from the publicity generated by two lawsuits: Serrano in California and Rodriguez in Texas. Both suits challenged the idea that the quality of a child’s education should depend on the wealth of his community.

In the Rodriguez case, the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly (5-4) upheld the constitutionality of the Texas school finance system, but suggested that reforms were in order regardless of the constitutional questions. The poor Mexican-Americans who filed the suit charged that the state denied them equal protection because the school finance system depended too much on the ability of the school districts to raise money from local property taxes. According to the complaint, residents of poor districts were forced to tax themselves at higher rates than residents of rich districts, yet they had little hope of raising as much money for quality programs.

The Supreme Court made its decision in the Rodriguez case in 1973; since then, the Texas legislature has chosen to appropriate millions of extra dollars for schools in 1975 and 1977, but without significantly changing the distribution patterns. The net effect of the legislature’s largesse has been that the rich are richer and the poor a little less poor. A few state legislatures in the South are beginning to enact measures to correct the inequitable distribution of funds, but those hoping for finance reform in many other Southern states, including Texas, are still waiting.

Under-funding of minority schools is by no means a new phenomenon. It was a central issue in the 1954 Brown desegregation suit, and in the South the problem has been especially acute. The concept of free public education did not catch on in the South until after the Civil War, when it appeared likely that Northern philanthropists would provide free public schools for the emancipated blacks. Even today, there are two Deep South states—Alabama and Mississippi—not under any constitutional mandate to provide free schools. (Both states introduced amendments soon after the Brown decision to free the state from any legal obligation to public schools.) In the quality of its public education, the South still lags behind the rest of the country, and minorities still suffer unduly from the reluctance of most states to ensure a just and uniform financial investment in the schools. Southerners still spend a smaller portion of their incomes on schools than other Americans.

As a result of this reluctance, the federal government today funds a greater share of school costs in the South than anywhere else in the nation—in some states two or three times the national average of federal aid, which is about eight percent. Some of this difference is due to the high number of military installations in the South, and also to federal programs based on poverty levels, which also favor the South. The ratio of state to local funding is also greater in the South than anywhere else. The combination of relatively high state and federal funding has kept the gap between the per capita budgets of various school districts in the South narrower than it otherwise would have been if they depended more on locally raised funds. Nevertheless, a serious gap does exist.

The problem of what to do about school districts which either cannot or will not come up with enough money to support their schools has been a constant source of concern to some state finance administrators. The first state contributions to school costs, in the early twentieth century, were in the form of flat grants: a certain number of dollars for each child or each teacher in a state system. The disadvantages of this system soon became apparent: certain schools needed more state aid than others, become some communities are obviously poorer than others. Some states, including North Carolina, still use the flat grant system, but most have gradually switched to an equalizing system known as a minimum foundation plan, which was developed in 1922 by George Strayer and Robert Haig.

The Strayer/Haig formula, as adopted by most states, has several basic elements. Each school district is required to tax at a certain rate; each district is entitled to a certain total amount of money for each student; if the local tax revenue cannot provide this amount, the state makes up the difference. The scheme sounds pretty good on paper. The hitch comes in the so-called “local leeway” option. Most minimum foundation plans allow districts to spend extra money, above and beyond the basic required amount, and naturally some districts have this extra money while others do not.

In addition to this built-in inequity in the minimum foundation system, local officials can tax at the required rate while at the same time making low assessments of property values; the local school revenue remains low regardless of the community’s real wealth, and more state money can be earned. As a result, a hodgepodge of assessment practices—some outrageously inaccurate—have arisen within different states. Correspondingly, a number of schemes to counteract these shady practices have also been developed, including economic indexes to measure wealth other than property. Not surprisingly, minimum foundation plans in the South have become patchworks of amendments and exceptions—difficult either to understand or administer.

The picture becomes even more complicated when you look at what happened to tax rates and assessment practices in Southern school districts after widespread desegregation began in the early 1970s, with its accompanying patterns of white flight and all-black school districts. Tax rates and school spending levels in many communities were either cut or allowed to stagnate, so that white parents would have money left over from taxes to send their children to private segregated academies. Many a school system which had previously operated on a blatantly “separate and unequal” basis, with poorly funded black public schools and richer white ones, now shifted its strategy of discrimination, and began operating a system of poorly funded, nominally desegregated (mostly black) public schools while in fact indirectly supporting a parasitic chain of segregation academies.

In South Carolina, for example, a detailed 1977 report released by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law showed conclusively that the tax rates in predominantly black districts were much lower than in mostly white districts. Furthermore, the situation in some historically black districts—which have never had much money for education—was getting worse. In Williamsburg County, where the white public school population has seldom been more than 28 percent, the tax rate was allowed to stagnate completely during the desegregation years, so that in 1974-75 the rate in that county was only 47 mills (or 47 cents per $100 of taxable property value)—compared with a state average of 82 mills per district.

Two school districts in Mississippi dramatize the situation in that state. The Anguilla district in the predominantly black Delta had a white enrollment of only 24.7 percent prior to desegregation in 1968, according to records of the Mississippi Department of Education. The tax rate was 25 mills. By 1975, the white enrollment dropped to 2.3 percent and the tax rate fell to 14 mills. And while property wealth in the state grew by 63 percent in the period, in Anguilla it grew by only 24 percent, giving rise to suspicions that, in addition to the substantial cut in the tax rate, property assessments were kept low. The result was that the local school revenue per pupil grew by only $26, compared to a state average of $85 per pupil.

Amite County, in the southwestern part of Mississippi, desegregated its schools in 1970 under a “voluntary” plan that resegregated its schools by sex. The plan was apparently designed to maintain the separation of white females from black males, but whites boycotted the public schools anyway. In 1968, enrollment in the county’s schools was 36 percent white and the tax rate was 25 mills. After the initial boycott, whites gradually returned until the percentage grew to 20 percent in 1975. The tax rate, which had been cut, climbed back to 17 mills where it remained in 1977.

In the fall of 1977, black students in Amite County refused to continue attending schools resegregated by sex. Blacks in the Anguilla Line School District also boycotted schools that year. Their protest started over the distances elementary students had to travel to school and soon broadened to a variety of issues, including the availability of school equipment and supplies, and the fact that the white superintendent—like all but a handful of white parents in the district—sent his children to a private, segregated school.

In both protests, the issue of inequitable financing of public education quickly came to the forefront. The controversy took on statewide implications in 1978 when a special study committee of the legislature recommended a complete overhaul of Mississippi’s 25-year-old school finance system. The proposals require that local school districts increase funding for public schools, and include a provision for the state to help school districts that can’t raise as much money with the same tax rate as others. The plan would also distribute state-collected school funds under a new formula based on student needs.

But before the plan can be implemented, the legislature must resolve the inequities in the taxation of property across the state. In January, 1979, a state court agreed with a lawsuit filed by a coalition of business, labor and education groups which charged that the lack of statewide assessment standards and the absence of a periodic reappraisal law has led to inequities in taxation among and within the state's 82 counties. The court ordered the State Tax Commission to ensure that state constitutional requirements for equal taxation be carried out.

Tax equalization is considered an important step in any statewide school finance reform. Low property assessments were among the chief reasons local school revenues remain low in the state, the school finance study committee concluded. But concerned public officials predict a rocky road ahead for school finance reform in Mississippi. The influence of private, segregated schools on certain key legislators is powerful, and the Mississippi legislature is not expected to address school finance issues in 1979. As the session opened in January, tax relief, rather than equitable financing and distribution issues, headed its agenda.

A number of other states, including Florida, Tennessee and Virginia, have been more successful in passing school finance reform bills. The most impressive victory came in South Carolina where a broad-based coalition of citizens overcame the power of private school interests to get a progressive finance bill for public schools approved in 1977. The League of Women Voters, which was among the leaders in the reform movement, counts the South Carolina bill as one of its special victories for public education because of the strong private school lobby. But the coalition's work is not done, says state League president Joy Sovde of Columbia. It must see to it that the legislature provides the funds to implement the plan, which commits the state to spend at least an additional $100 million for schools over the next five years. However, a controversial two percent ceiling was placed on the amount of increased funding from year to year in any category under the state minimum foundation program - a move apparently designed to contain educational costs.

A "pupil weight" system was also adopted; this is an innovative scheme (also now used in Florida and Tennessee) for distributing state money to the schools on the basis of which kinds of students take the most money to educate. In a pupil weight system, a base category of students is defined - having supposedly average educational needs - and is assigned a weight of "1." Other categories of students are then defined in relation to the base, and are assigned weights greater or lesser than "1" according to their various needs. Students in remedial programs, for instance, are generally assigned heavy weights because these programs require costly high teacher-pupil ratios. Money is then appropriated according to the assigned weights.

The states which have revised their school finance systems have consequently encountered some major obstacles in trying to implement the changes. For one thing, the pupil weight system - like any other funding scheme - is vulnerable to political manipulation. Florida has had to put a cap on the number of pupils it will fund in each category to discourage school officials from channeling students into heavily weighted programs simply to get more state money.

But the primary obstacle to finance reform has been the pressure from taxpayers on state legislatures to renege on their new, increased financial commitments to the schools. (Almost every reform package calls for the state to increase its share of the total education budget.) In Florida, state education officials say the school finance system is now "equalized but under-financed"; the state, they say, has not made up for the decrease in local funds. Officials in Tennessee, South Carolina and Virginia make the same complaint. The state legislatures, these officials conclude, have enacted some much-needed reforms, but the states' real financial commitment to those reforms has yet to be proven.

Those Southern states which have made any efforts at school finance reform - however incomplete – are still in the minority, despite the fact that this decade has seen unprecedented economic and population growth in the South. Because the 1970s should have been a prime era for school improvement and school finance reform, grave questions have now arisen as to how well the South is controlling - and distributing - its new wealth. Southern states still depend heavily on the sales taxes - which disproportionately hurt poor people - to fund state budgets. School revenue leans especially hard on the sales taxes. At the same time, many Southern states tax property value, intangible wealth, personal income and business income at a far lower rate than the national average. The poorest state in the union, Mississippi, depends heaviest on the sales tax, receiving 45 percent of its general revenue funds for the 1979 state budget from the five percent sales tax; that proportion is more than twice the national average.

A study in Mississippi concluded that the recently outlawed 10-year tax exemption for new industry was in part responsible for keeping school revenue in the state so low. The mammoth DuPont Corporation managed to win a partial exemption from school taxes for a chemical plant it is building in the Pass Christian, Mississippi, school district. The exemption was granted in December, 1978, just days before such exemptions were outlawed in the state. South Carolina has now outlawed these exemptions too, but many other states have not.

Ironically, the South may be selling its schools short for no real purpose. Educational consultants Jack Leppert and Dorothy Routh reported on a number of studies of how industries pick the South to build in. The most important factors were access to markets, labor costs, availability and skill of workers, and supplies and resources. Tax concessions were not among the major considerations. "This unnecessary catering to industry," noted Routh and Leppert, "may have lost us many valuable tax dollars that could have been utilized in developing human resources which ultimately make the area more attractive." In other words, how many rich Northerners are willing to move to a community when their children will have to attend poorly funded, inadequately staffed, underachieving schools?

Many prominent Southerners are defensive about the low level of school spending in the region. They cite differences in the cost of operating schools, and point also to low per capita income. Besides, they say, there isn't necessarily a vital link between high spending and good education.

Some of these points are well taken. To put the argument in its proper perspective, however, one must take a hard look at what the South has gotten for its money over the years. One stark set of statistics, for example, is the 1974 results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress: the South’s 17-year olds scored below the national average in every area tested, which included science, writing, citizenship, reading, literature, music, and social studies.

Even the most recalcitrant Southern state legislatures are beginning to realize that something must be done about the inequitable and unwieldy condition of school finance. But few have taken any real action. Property tax revision, in the experience of several states, is a prerequisite for school finance reform, and heavier personal income taxes also appear necessary if poor people are not to continue carrying the greatest burden of school funding through sales taxes. A high level of state funding for education seems to offer the best hope for equalizing spending in each state’s districts; however, local funding will always be important, if only to maintain community interest in the schools. Important in any good finance reform package will be a provision to ensure that local participation in school funding is accurately related to the local ability to pay, so that state money will go where it is most needed. The new “pupil weight” schemes appear to be the best method now available for distributing money to the schools, though much more work needs to be done on developing fair weights.

The case for better financing of Southern schools is clear. Yet, as state legislatures consider proposals for school finance reform, pressure mounts from the electorate for tax relief. “Proposition 13” is a popular rallying cry. For school systems already in dire need of basic equipment and services, nothing could sound more ominous.

Tags

Linda Wiliams

Linda Williams has reported on education topics for the Raleigh News and Observer, the Delta Democrat-Times in Greenville, Mississippi, and the South Mississippi Sun in Biloxi. In 1978, she conducted a study of school finance patterns in the South as a Ford Foundation Fellow in Educational Journalism. She is now a staff writer for the Portland Oregonian. (1979)