This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

“DON’T LET TENNESSEE STINK’’ reads the caption on the child’s poster hanging in the office of Dr. Joseph Smiddy in Kingsport. Belching smokestacks tell the rest of the tale. Dr. Smiddy is the only lung specialist in Kingsport, and for several years he has tried to alert the people of the area to what he terms a “continuing, permanent epidemic of respiratory disease.”

No visitor to Kingsport can miss the fact that the town smells. But industrial pollution is more than an aesthetic problem, more than a problem for plants and animals, birds and fish. In Kingsport, some people are concerned that the air they breathe and the water they drink may seriously affect their health.

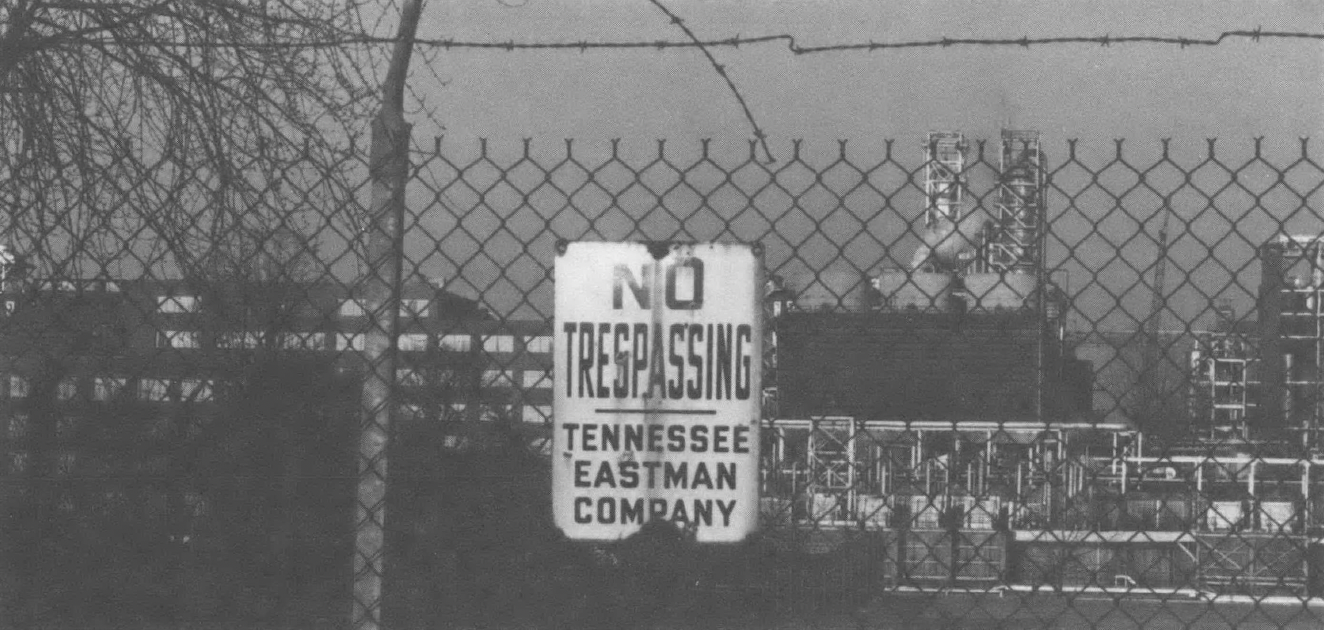

Tennessee Eastman Company — the largest employer in Tennessee, and part of Eastman Kodak — dominates Kingsport. The town began as a port on the Holston River, an important transportation link for settlers heading west through the Cumberland Gap. In the early twentieth century, a small band of entrepreneurs decided that the Holston River site would be ideal for a manufacturing city. It had raw materials, good communications with the rest of the country, an adequate supply of water, and good country people to provide a compliant workforce. In 1920, Eastman arrived and transformed a wood alcohol plant into what is now a huge chemical complex. With it, the character of the town was transformed. Today, with a population of 33,000, Kingsport is the industrial center of a mainly rural and agricultural upper east Tennessee. Communications are still good, the workforce is still compliant — the major industries in the town have no union. But in the course of its development, the natural environment of the town and its surroundings have been damaged, and with it the health of its people.

Dr. Smiddy says that many people, on moving to Kingsport, develop bronchial problems, and loss of their full breathing capacity. Like Kingsport natives, new residents are likely to suffer continuing sinus problems and coughs. People in Kingsport got very excited last year by an outbreak of Legionnaires’ Disease — there were sixty-six cases in Kingsport. But Dr. Smiddy expresses as much concern about the year-round epidemic of respiratory disease.

Perhaps the worst health problems exist for the 14,000 employees of Tennessee Eastman and the 2,000 of the Holston Army Ammunition Plant, run by Eastman for the federal government. In its Kingsport plant, Eastman manufactures fibers (acetate, modacrylic and polyester), plastics (cellulosics), dyes and industrial chemicals. Tennessee Eastman is a division of Kodak, the second largest chemical company in the US and among the largest in the world. Behind the familiar image of every kid’s first Brownie camera lies another reality for workers.

A growing recognition of the dangers of such workplaces led Congress to pass the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 and set up an agency, OSHA, to enforce its provisions. But according to TOSHA, the Tennessee office of this agency, no inspections have been conducted at Tennessee Eastman. Don Witt, head of the Tennessee office, said, “One of the reasons why we never inspect the big companies is because the companies have excellent programs themselves. We don’t go in because we know we probably won’t find any violations.” A former OSHA employee told a different story, however: “They (OSHA) really try to skirt the problem and Tennessee Eastman is too big for TOSHA to handle.”

Since OSHA began, it has been increasingly apparent that the dangers of the workplace extend beyond the plant to the community into whose air and water it discharges its wastes. In 1976, Congress passed the Toxic Substances Control Act, which theoretically enables the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to control harmful substances manufactured and used by large companies. It is a weaker version of a bill proposed in the Senate two years before and vigorously opposed by the biggest chemical companies — Eastman Kodak, Dow, DuPont and Union Carbide. The new bill is limited to substances known to be dangerous — it does not allow for control of potentially harmful or suspected substances currently being made.

These acts of Congress follow increased national and international discussion about environmental health hazards. The National Cancer Institute recently suggested that eighty to ninety percent of all cancer results from environmental pollution. Out of the thousands of chemicals manufactured each year, only a handful have been studied sufficiently to determine their toxicity; many more are suspect. And because it may take decades for birth defects, cancers, and other diseases to become alarmingly apparent, concerned citizens must look for the early warning signs in places where population and industry are most dense. With its mix of paper, concrete and textile industries, plus Eastman Kodak’s chemical division and munitions plant, Kingsport is a prime case study.

PAYING THE COSTS

In spite of increased awareness of environmental health hazards, there is little public concern expressed in Kingsport. Residents are understandably reluctant to criticize the industries which put bread on their tables. As the local newspaper comments, Kingsport “smells like money.”

But there are hidden costs behind that smell. Workers and local residents have to pay their own doctor bills, and the neighboring rural counties, downwind and downstream, are also affected by the city’s pollution. In the surrounding area the rate of babies born with abnormalities is more than twice the state average.

In the chemical industry world, Tennessee Eastman ranks high in the amount spent on new control devices, but little is known about the actual harmful effects of the materials used. And Eastman employees are not told the real (generic) names of the chemicals they handle. The wife of one worker told how, even after a week’s holiday away from Kingsport and numerous baths and showers, her husband’s skin still smelled of acid — but neither she nor he know what kind of acid. The 1970 Occupational Health and Safety Act might have given employees the “right to know,” but it has not been interpreted in this way. Now a national campaign is being waged by public interest health groups to get this right recognized in OSHA regulations. Meanwhile, workers at Tennessee Eastman deal with “number 9123,” or with chemicals under their trade names.

Tennessee Eastman also tries to avoid paying compensation to workers who think their ill health is attributable to workplace hazards. Dr. Smiddy has experience of several such cases. He tells of one occasion when he was treating a Tennessee Eastman worker who was “gasping for breath.” He tried to get information from the company about the chemical the man was working with. “Sorry — trade secret,” replied the Tennessee Eastman doctors. Although the company has a large staff of physicians and extensive laboratory facilities, they share very little with the local physicians who treat their employees. However, local doctors know that Tennessee Eastman keeps check on employees who work in high-risk areas, and in some sections they carry out sputum cytologies every six months — the worker may not know the name of the chemical he handles, but he and his doctor can be fairly sure it is dangerous if he is one of those who “spit in the can.”

DON’T BREATHE THE AIR

“I’ve lived here five years and practiced medicine, and there’s never been any information printed in the newspapers that anybody was harmed, but patients can tell you that ‘my buddy who worked on the bench to my left is in Duke Hospital gasping for his breath, and my buddy who worked on the bench to my right is in the University of Virginia Hospital gasping for his breath. ’ But in addition to breathing problems and lung damage, a lot of other things have happened: blood disorders, and some people who’ve worked in the same division developed neurological disease. There was a group ofpeople working together on a chemical product who developed a form of paralysis. But you never read about this in the paper. The only way you get it is through the grapevine. Some of the grapevine is probably inaccurate, but i have the feeling as a physician that I’m seeing the tip of an iceberg. ” — Dr. Joseph Smiddy

“Disability is a dirty word” in Kingsport, says Dr. Smiddy. “Even to talk about disease, disability or pollution is considered a criticism of industry.” Many local physicians regard Dr. Smiddy as an object of amusement for his strong protagonist role; they themselves do not seek to change the unchangeable. But an examination of the history of Kingsport reveals how local industry has defined what is unchangeable. The transformation from sleepy river port to industrial complex was planned carefully from the top. With the aid and advice of outside industrial planners and the Rockefeller Foundation, the town fathers imposed the city manager form of government on Kingsport in 1917. An efficient governing force from the point of view of industry, it takes the important local offices out of the hands of voters. In recent history, workers in Kingsport have been paid more than the average wage for workers in the surrounding rural counties; the price they are expected to pay is silence.

Not all residents accept the promoted silence. Especially in those aspects of the industries which affect the community, there have been protests. Air pollution particularly has caused a flurry of interest and criticism in the last couple of years. The Kingsport Times-News carried a frontpage report on February 5, 1978, of a survey among residents of the Kingsport area. Thirty-nine percent of city residents placed air pollution at the top of their list of “most severe problems.” The figure rose to forty-six percent among those city residents who are also members of civic clubs, and fifty percent among residents outside the city. No other problem came near the agreement about dirty air.

West Kingsport has long received the bulk of the fall-out of dirt, dust and industrial wastes in the air. During 1976 and 1977, fifty-three residents signed a petition to get a study of the air pollution of Kingsport industries, and twenty-three of them blamed the bad air for their own health problems — asthma, bronchitis, allergies, lung troubles, chest pains. Others cited physical discomfort, itching and rash. After pressuring the Air Pollution Control Division of the state of Tennessee for a year, the residents met with its director, Harold Hodges.

They told him that the fall-out was always worse at night; they suspected that the incineration of wastes was increased by the companies when it was less visible. Because residents could see the silos at the Penn-Dixie concrete works “bubbling over” with dust, they suggested it was cement dust in the air. The Division of Air Pollution Control made a year-long study of the problem, at the end of which a spokesman said they were “developing a body of circumstantial evidence that would suggest cement and masonry products are the primary problems in Kingsport.”

While residents were pleased that at long last the inspectors had made a study of the problems they had been living with for years, many also felt that it was too little and too late. The study dealt only with particulates, and only with six firms in the city. Tennessee Eastman was notably absent from the study, as are the substances in the air which have the greatest long-term health effects. In the words of a local pediatrician, William Griffin, “The problem here is what we smell, what we can’t see, and what we don’t monitor and don’t know what it is.”

An interviewed spokesman for the Air Pollution Control Division admitted the need for an in-depth study of Tennessee Eastman’s emissions of organic chemicals into the air. He said that no studies have been conducted on gaseous emissions, and that much more sophisticated equipment would be needed in Kingsport to study such problems. “Tennessee Eastman is burning off chemicals and getting all kinds of exotic combinations; no one knows what effect they will have. Rarely do they get complete combustion from incinerators, and they are burning off chemicals we don’t know anything about.”

In response to federal and state environmental controls on their waste disposal into the Holston River, Tennessee Eastman says that their “incineration operations have become more complex in recent years, as the program to protect water quality has necessitated the incineration of solid wastes.” In reply, Dr. Griffin says, “I’m breathing what the fishes used to breathe, and not only am I breathing what they used to breathe but (in) burning the stuff, they’re making all kinds of mixtures; they don’t even know what they’re creating in the air. I think we have to be defensive about our health. It’s foolish to ignore. If your lungs tell you there’s something there and you start coughing and hacking and your sinuses get congested, your body is trying to tell you there’s a problem — you know there’s a problem.”

DON’T DRINK THE WATER

Through wind and water, the legacy of Kingsport spreads across the surrounding areas. About 350,000 people live in the Holston River Basin; even miles from Kingsport, they still bear some of the costs of that industrial complex. Day in, day out, Tennessee Eastman releases 350 million gallons of waste water into the Holston River, sixty-five percent of the total daily discharges of all industries into the river. At times of low flow, in the summer months, all of the Holston River has to be diverted into the Eastman plant. Don Owens, biologist with the state of Tennessee Water Quality Control Division, says of Eastman, "It is too big an industry for the size of the river.” The only way Eastman can get enough water from the river for its needs is through the cooperation of the Tennessee Valley Authority. TVA has agreed with Eastman to release extra water from its upstream Fort Patrick Henry Dam to meet Eastman’s requirements of a minimum of 750 cubic feet per second.

A classic example of what happens when a polluting industry cleans up just the minimum required by regulatory agencies, and no more, is seen today in Kingsport’s plague — black flies. To an outsider, the clouds of tiny insects in the city and surrounding Sullivan County, and in neighboring Hawkins County, may not seem a problem for concern. To the people of these areas, however, they are a scourge, making life outdoors miserable from April through the summer. An army environmentalist team told the local newspaper that Kingsport had the worst black fly problem they had seen. Dr. Ed Snoddy, an authority on the black fly, now works with TVA’s Water Quality Branch, and says that black flies are “pollution followers — to a point.” In days past, when the Holston River was so heavily polluted that nothing could live in it for miles downstream from Kingsport, there was no habitat for black flies either. Now the water quality has improved slightly, “into a regime within the life zone frame of this species of black fly,” says Dr. Snoddy, but not to the point where “normal predators and natural control mechanisms” might prevail.

As a result, the insects thrive. They swarm around animals and humans, attracted by the carbon dioxide in breath. Their bite leaves a large, angry welt, and some people are even more sensitive to them. One hundred cases of bad reactions (severe itching, swelling, pain) to these bites were reported in Kingsport in 1976. The females are blood suckers and carry disease among wildlife and animals. Dr. Snoddy says that there is little evidence that they transmit disease to humans, “but there may be some things we don’t know about .... there are many obscure viruses which may be associated with them.”

Treatment of the black fly problem is by yet another chemical, ABATE, which has itself caused some controversy. EPA has registered its use as safe only in the concentrations used for midges and mosquitos, not the greater concentrations necessary for black fly control. A special exemption allows its use in Kingsport. It is ironic that a problem caused at least in part by chemical pollution should have to be treated with more chemicals whose long-term effects on human health are also unknown. Again, the costs of pollution are met by the community. Spraying the chemical onto the water helps control the black fly problem; its cure can come only with the return of the river to a healthy balance.

If Dr. Griffin thought that the fishes in Kingsport’s water are getting a good deal compared to the humans in its air, water quality specialists would disagree. The river flows on, many miles downstream of Kingsport, through rich farmland and rural populations, carrying the wastes from the city of Kingsport down to TVA’s Cherokee Lake and Morristown, and perhaps beyond, through the city of Knoxville into the Tennessee River, 140 miles downstream of Kingsport. According to the state Water Quality Control Division, “the most extensive degradation of water quality in the (Holston) basin exists in the Kingsport area.” It identified the major polluters as Tennessee Eastman and its Holston Army Ammunition Plant, and the Mead Paper Mill. State biologist Don Owens says, “Eastman is probably the most difficult chemical problem in the state right now.” Downstream of these discharges, as far as Knoxville, the state says, “water quality presently violates applicable standards. It is not expected to meet the standards even after the application of best practicable control technology for industry and secondary treatment for municipalities.”

Several agencies — EPA, the state, TVA — monitor and report on water conditions in the Holston River and Cherokee Lake on an occasional or regular basis. Yet to the concerned layperson, study of such reports indicates one factor of overriding importance: we know very little about the extent of the damage being done. True, samples are taken; true, they are analyzed. But the standard water quality tests are for characteristics of the water like oxygen level and temperature, factors more important to fish than to human health. The organic chemicals and metals which are discharged into the river by the chemical companies upstream are seldom monitored. Yet it is just these substances which are currently causing scientists more concern for their possible effects on human health.

To analyze even a single sample of water for these substances is a very expensive process — it may take thousands of dollars for a single sample, especially if the combinations of chemicals involved are as complex and little known as those dealt with at Tennessee Eastman. In a recently published analysis, EPA found at least two chemicals that are known to be toxic. Others in the sample are known to be health hazards in the workplace, but their effects in drinking water are generally unresearched. The box “Chemicals in the Water” lists a few of the chemicals found.

In addition to the organic chemicals, there are metals in the discharges that also may affect human health. Tennessee Eastman’s discharge of manganese at 9,500 pounds a day is well above the recommended limit for public health. Copper, lead, zinc and chromium are also known to have deleterious effects on human and animal health in some circumstances; these, too, are found in the Holston River below Kingsport.

But the biggest publicly recognized health problem in the Holston River right now is mercury, and its source is even more difficult to regulate than Tennessee Eastman. The Olin Matthieson chloralkali plant at Saltville, Virginia, used mercury for many years. When it closed in 1972, unable to meet environmental regulations, it left its legacy in the muck ponds of the old industrial site. From them the heavy metal seeps out, day by day, into the North Fork of the Holston River. It drops into the sediments of the riverbed, there to be converted by bacterial action into a highly volatile and toxic form, methylated mercury. It is released into the water and the air, but more importantly, is easily absorbed by fish. A community in Japan was poisoned by eating shellfish contaminated with mercury, and gave its name to the resulting disease, Minimata Disease. This is a severe disorder of the nervous system which can be fatal. There have been no recorded cases of Minimata Disease among the popula- tions which have been eating fish from the North Fork of the Holston River as long as the plant has been in existence. But TVA’s own expert on mercury suggested that its symptoms are like those of other neurological disorders, and doubted whether any cases that might have occurred would have been diagnosed as such by local physicians. The Virginia Public Health Department became so concerned by reports of fish with mercury levels above FDA limits that it closed the North Fork to fishing, subsequently allowing fishing for sport only. But who can police the miles of riverbank to ensure that no fisherman, catching an apparently healthy fish, takes it home to eat?

The mercury pollution extends well beyond the neighborhood of Saltville. Mercury in the sediments of the river apparently passes downstream, beyond Kingsport, to Cherokee Lake where the metal is found in some fish at levels above FDA limits. But the state of Tennessee has not yet decided to ban fishing in the lake.

Obviously, water can carry substances a long way. When the Olin plant was operating, its massive discharges of calcium carbonate made the water “hard” as far downstream as Lenoir City, 275 miles away.

“Cherokee Lake is dying,” says Pat Card, who, with her husband, runs a boat dock on the lake, and, like other operators, depends on the lake and the fish for her livelihood. The boat dock operators present a grim picture of fish kills, stunted growth among game species, and fish with open sores. Dewey Smith has been on the lake five years, and thinks that 1977 was the worst for pollution. His boat dock operation lost $15,000 to $18,000 in income last year. “No one wants to put a $7,000 boat in water that looks like coffee grounds.” Pat Card says also that people around the lake who suffer scratches often develop infections. She wants to know what chemicals are going into the lake, and what effects they have, but no one will — or can — tell her.

What can people do when faced with these kinds of threats to their livelihoods? There have been hearings and meetings about the state of the river and lake, but they do not offer much help to ordinary people who, when faced with the “experts,” are often silent. Dewey Smith went to one hearing on the state’s water quality plan, but “I didn’t say a word during the meeting . . . Eastman had fifteen lawyers; what’s a man with a high school education going to say to a bunch of college professors?”

Tennessee takes the view that the waters of the state are the property of the state, held in public trust for its people. In 1975, the state Water Quality Control Division made an extensive survey of the whole Holston River basin, listing all discharges into the river from industries, municipalities and other sources, and making proposals for the control of pollution from these sources. The report stated that “the people of Tennessee, as beneficiaries of the [public] trust, have a right to unpolluted waters.” Tennessee Eastman objected to the water quality control plans, however, and sued the state in November, 1975.

This suit was dismissed after the state agreed to some concessions. As Tennessee Environmental Council’s Jonathan Gibson said of the weakened standards in the new plan, “The people lost.” Gibson spoke at public hearings on the revised water quality control plan, held in Morristown in November, 1976. “It does not take an attorney to be appalled at the way the Tennessee Eastman Company has used legal, political and economic threats to escape full and equitable compliance to the water quality laws of our state.”

Constant daily pollution of the waters of the Holston River by industrial users, past and present, is one form of environmental health hazard. Another, sometimes more dramatically visible to people in the river basin, lies in the “spills,” accidental or otherwise, from those same industries. Says biologist Don Owens, “It used to be that they would dump everything into the river without telling anyone .... Eastman has got a lot better at reporting spills.” Today, the list of chemicals reported by Eastman to have been spilled into the Holston River is alarming enough; there is no speculating on the proportion of unreported spills. The box, “Chemicals Spilt by Tennessee Eastman,” shows just a few from the long list reported by the company in recent years.

“Eastman’s chemicals foul Morristown’s water supplies”; "Morristown hauls water for drinking”; “It should not happen again!” — so was the dramatic news broken to Holston Valley people of a spill from Tennessee Eastman that could not be ignored. On February 4, 1977, Eastman employees washed approximately 7,000 gallons of ethyl pivalate into the storm drains leading to the Holston River. A report to EPA stated that the chemical was nontoxic, and that it would be dispersed by the time it reached Morristown, the first intake for drinking water downstream of Kingsport. The weather was against Tennessee Eastman, however; the river was very low and very cold. The chemical stayed in a mass, and a week later, citizens in Morristown began besieging their utility commission with reports of a foul taste and smell in the water coming out of their taps. Reports compared the smell with walnuts, cherries, sewage and rotten eggs.

Morristown’s residents must have empathized with Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner — “Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink.” Drinking water was supplied to the 75,000 people deprived of clean water through two tankers parked at shopping centers. Water was brought to the elderly and infirm in their homes. Beauty salon operators had to rinse their clients’ hair in vinegar to get rid of the grease left by the water. Plants died when watered with it; pets refused to look at it; the FDA ordered a Royal Cola bottling plant to cease operations. But everyone’s main question was, “Is it toxic?” The answers they received were various; they are set out in the margin.

At least one local doctor was sure that the chemical was having ill effects on his patients. At a public meeting, Dr. Donald Thompson said that he had “several patients exhibiting an allergic reaction to the chemical and has had several reports of children suffering from severe diarrhea.” Tennessee Eastman’s officials claimed the chemical was nontoxic, but under questioning it became apparent that they really knew very little about the effects of ethyl pivalate on people.

Local feelings ran high. A $37.5 million class action law suit was taken out against the utility commission and Tennessee Eastman by two local businessmen. The chairman of the utility commission said that the Holston River “was created by God for His people and His creatures, and it must be cleaned up.’’ As Dr. Thompson wrote to the local paper, “There’s too great a risk from those chemicals which we can’t see, feel, smell or taste — after all, we don’t know what the long-term ingestion of such chemicals as those used by Eastman do to our bodies, but we can safely predict that it is not GOOD for us.’’ The Morristown Citizen-Tribune voiced the fears of many of its readers when it asked in an editorial, “What if ethyl pivalate had been odorless and tasteless? Would we, the water customers, even have known anything about the spill? . . . What if it had been odorless, tasteless and toxic?”

In December, 1977, Morristown lost its “approved” water status. Michael Stanley of the state Water Quality Control Division said that Morristown’s water supply is “the worst in the state,” and “the water being pumped into their water filter plant compares with water going out a secondary treatment plant. It’s unreal the kind of water they are pumping into their plant.” Morristown residents recognise only too well the jobsversus- environment arguments, but as Dr. Thompson wrote, “an industry that poisons the people and its own workers is certainly NOT needed by ANY community, lest Morristown ends as did Seveso, Italy.”

Tennessee Eastman declined to participate in our investigation. The company said they were too busy preparing the list of chemicals they manufacture and use which EPA requires under the new Toxic Substances Control Act. The puzzled layperson might well suppose that a company would already know what it manufactures. And whether or not this list will be publicly available in the next few years is uncertain. When asked about this, an EPA official replied, “You better get yourself a good environmental lawyer,” and he cited the company’s right to “trade secrets.” Tennessee Eastman’s employees, lacking a union, have no place to turn when they are worried about the hazards of their workplace. Citizens’ groups haven’t the resources to analyze a company’s products and emissions either. Employees do not know what chemical they are working with, and know it is dangerous only by the fact that they are tested, but they are not given the results of those tests. Doctors are not told what chemical makes a patient sick, so that he or she can be treated; the community is not told what is in the air it breathes and the water it drinks — “trade secrets” have been taken too far.

Why are we concerned about the chemicals Tennessee Eastman produces? A good part of the answer lies in an exchange reported in the American Public Health Association journal, The Nation’s Health. At a meeting on toxic substances, a chemical company attorney was heard to wonder aloud, “Why do people ask one particular industry (chemical) to create a risk-free environment? No other industries are required to do that.” The answer came back quickly: “Because those substances kill people, that’s why.”

Tags

The Kingsport Study Group

We are teachers and students in the Kingsport and Holston River area, who have an interest in health and environment and a concern for the people of the area. We continue our interest and our concern beyond this article, and invite the participation of others. Beth Bingman, Jamie Cohen, Steve Conley, Maxine Kenny, Helen Lewis, Juliet Merrifieid. (1978)