This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 1, "Building South." Find more from that issue here.

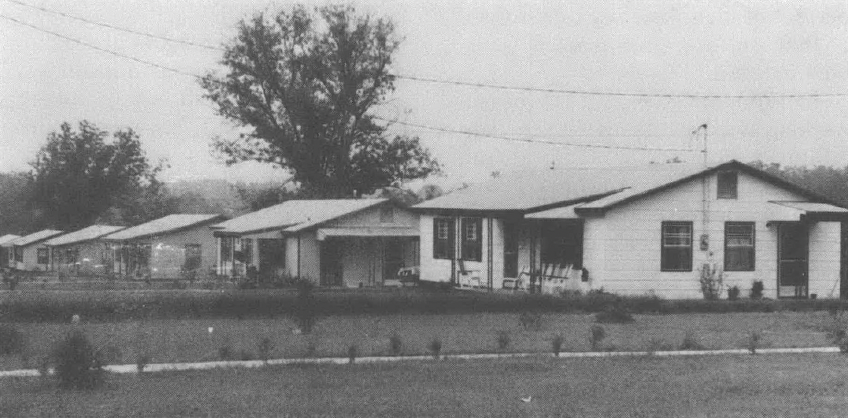

When Clarence Jordan and his followers announced a new direction for Koinonia Farm in 1968, one of the stated goals of the Christian community near Americus, Georgia, was to build low-cost housing for poor families. Now, 11 years and 85 houses later — and 10 years after Jordan’s death — housing for the poor is both an accomplishment and a continuing challenge for Koinonia Partners.

Jordan, his wife Florence and the others who started Koinonia in 1942 endured years of hostility and isolation for daring to create an interracial agricultural community in the midst of rigidly segregated south Georgia. Their widely publicized ordeals brought them considerable moral and financial support from safe distances — but precious little from close at hand. The Koinonia residents held on against persistent white opposition, and by the time a white farmer from nearby Plains had been elected president of the United States, the community had become a permanent fixture on the red clay soil — a presence tolerated if still not fully accepted.

By raising pecans, peanuts, cattle and row crops on 1,400 acres of land, and by marketing handcrafts, fruit cakes, candy and other cottage-industry items through mail-order sales, the people in the Koinonia partnership have kept their continuing experiment in communal sharing alive for 37 years. Their housing enterprise, financed chiefly by tax-deductible gifts and interest-free loans, has extended the principle of self-sufficiency beyond the Koinonia community itself to make it possible for at least a few of their Sumter County neighbors to afford decent housing for the first time.

The Fund for Humanity — Koinonia’s repository for gifts, loans and the profits from farming and mail-order sales — disburses money for the construction of homes, which in turn are sold at cost to poor families. The first houses, built a decade ago on Koinonia land, cost just $6,500 each. Currently, houses being built on land purchased in Americus cost $20,000 each; for these, residents make a $700 down payment and pay about $80 a month on interest-free 20-year loans.

Experience and necessity have caused the Koinonia builders to make numerous changes in their construction program over the years. For one thing, they have shifted their focus from the rural countryside to the city of Americus, where 20 percent of the existing housing is said to be substandard. For another, they have given families a wider choice of floor plans, siding, roofing and interior design. The newer houses are also somewhat larger — 1,100 square feet, on the average — with improved insulation and other energy-conserving features.

The Koinonia housing program is primarily in the hands of Arthur Pless, a Sumter Countian for most of his life, and 27-year-old John Dorean, a native Pennsylvanian who first came to the community as a volunteer worker in 1974 and returned to stay in 1976. Pless is the coordinator of the crew of six to eight men who build the houses; Dorean is the materials and supplies coordinator.

“We’re completing 12 houses a year, one a month,” Dorean says. “The plumbing, wiring, heating and rock work is subcontracted, and our crew does the rest. We’re getting the best possible quality for the least possible cost. Right now, the cost works out to about $18 or $19 a square foot — and that includes the land, the labor and all materials.”

Adds Pless: “We don’t waste anything, not even scrap lumber. We’ve got about 10 house plans for families to choose from, and through trial and error we’ve learned to conserve space and improve insulation. Little things, like putting closets on the north wall and windows on the south, have helped a lot. We’re also beginning to use some solar techniques for such things as water heaters. There’s no doubt that the houses we’re building now are of a better quality and more energy-efficient than the first Koinonia houses.”

A special committee of the Fund for Humanity reviews applications for the housing and approves the loans. “The people who live in these houses are not the poorest of the poor,” Dorean says. “They have to be able to come up with the down payment and the monthly payments. The need for housing is so great that there’s no way to help everybody.” The average income of families living in Koinonia housing is about $400 a month, which classifies them as “working poor.”

Of the 85 families to receive housing so far, only three have subsequently sold them to other families — and not a single one has defaulted on the loan. Koinonia retains ownership of the land on which the houses are built, and has first option on purchase of the houses — when and if they go on the market. The need for decent housing is so great and the interest-free loans are so attractive that turnover of the properties has simply not occurred.

“What we’re doing is just a drop in the bucket,” says Pless, “but for me, the results are very satisfying. I’ve spent a lot of time working in the area of civil rights and voter registration. But now my productivity is direct; my work results in houses, something I can see. I used to be in the moneymaking business and I’d just spend the money I made on myself. Now I’m building houses for people who need them. I’m doing more than making money - I’m doing service to my fellow men and women.”

Dorean agrees. “This is a positive way of expressing your feelings about society,” he says. “When you liberate people physically, you help to liberate them spiritually.”

Given the modest and conventional nature of the Koinonia construction program — the standard designs, the meticulous conservation of materials, the comparatively low labor costs — the $20,000 price tag on the houses can only be seen as a sobering sign of the inflation-plagued times. Without benefit of government aid, Koinonia raised a million dollars in a decade and used it to free 85 families from slum dwellings. But even if it raises another million dollars in the 1980s and adds to it the funds received from repaid loans, continued inflation will inevitably reduce — not expand — the number of new houses that can be built. At current prices, a million dollars would build only 50 Koinonia houses; by 1990, it might not produce Steve Clemens and William Thomas even half that many.

“Ten years of concentrated work have hardly begun to make a dent in the housing needs of one county, in one state, in one country,” John Dorean says. But in the Koinonia spirit, he and Arthur Pless and their companions labor on, undiscouraged. And for 85 Sumter County families, the dent Koinonia has made is not so small.

Tags

John Egerton

John Egerton is a Nashville-based freelance writer. His fifth book, Generations: An American Family, will be published in 1983 by the University Press of Kentucky, after being turned down by more than a dozen commercial publishers.(1983)

John Egerton’s latest book is Nashville: The Faces of Two Centuries. (1980)

Tennessee free-lance writer John Egerton is teaching magazine journalism at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg this year. (1978)