This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 1, "Behind Closed Doors." Find more from that issue here.

We lived for 10 weeks with a working-class family and their nine children in Cuernevaca — the land of “eternal springtime.” Cuernevaca is wedged into a valley at the foothills of mountains that lead up to Mexico City. Here, nine centuries ago, lived the Aztec people; here was the summer home of Montezuma and later the victorious “conquistador” Cortez. Just to the south of Cuernevaca lie some of the richest sugar cane fields in the state of Morelos — and all of Mexico.

Today, Cuernevaca is the home of another invader — Burlington Industries, the multinational textile company based in North Carolina. As with previous conquerors and oppressive regimes, the presence of Burlington and its harsh treatment of the 1,500 employees in the area’s four mills has brought considerable conflict to the town. This is a region with a long history of struggle.

In the sugar refineries, the blackened bodies of the “caneros” covered with dust evoke memories of the revolution. Sixty years ago, Emiliano Zapata marched at the head of thousands of “campesinos” under the banner Tierra y Libertad: Land and Freedom. On these same communal lands, or “ejidos,” the father of the family with which we were living was born. And his father still works the same sugar fields, still plows the land with horses, still remembers the revolution in which more than one million people — out of a population of 15 million — perished. When the revolution began in 1910, 97 percent of the land was owned by 830 people or corporations, two percent was held by 500,000 small and medium scale farmers and the balance by municipalities. Today, the state of Morelos has usurped the cry of the campesinos: “The land will return to those who work it with their hands.” But the reality is otherwise: 78 percent of the land in Mexico remains in the hands of 1.5 percent of the people.

The “colonia” (neighborhood) we lived in is called Teopanzolco, which, in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs, means “the place of the gods.” Just beyond the colonia, across the railroad tracks, lies one of the many pyramids built by the original inhabitants. The modern colonia was built with the help of Burlington Industries’ subsidiary, Textiles Morelos. And as in the milltowns of the southern United States, the lives of the mill workers are largely determined by the company.

The father of our family was fired from the mill nine years ago for his union activities, and blacklisted. In order to support his family and his six children, he moved with them into a “casa de carton” — a cardboard shack — and rented their first house to other families. Unable to find steady employment, and with some skill as a plumber, he goes out each day to contract work — for a day, three days, however long he is needed. A plumber, like a carpenter or painter, must work 10 hours a day to earn 65 pesos (sometimes 90) — about S3.00 a day, or 30 cents an hour. More often than not he does not find work. But he is not alone: one out of every two workers is underemployed. More than 10.5 million — in an economically active population of 17.5 million — are without full employment in Mexico.

In the kitchen, the mother of our family is stirring a pot of “frijoles,” or beans, our staple diet. She does not count among the 3.5 million women who make up part of the “economically active population” although her work is just as long and just as tedious. On the table is a stack of tortillas. These two — beans and tortillas — must suffice to feed the nine children she has borne into this world. She does not usually make the tortillas, for they can be more readily purchased from one of the many “tortillerias” in our neighborhood, now a multinational business in the larger cities of Mexico. Even the yellow com from which they are made is not from Mexico but is imported as field com from the US, where it is fed to livestock. Mexico, in turn, exports its white com to the tables of North America. The volume of trade between the two countries accounts for more than half of Mexico’s trade. And the majority of winter vegetables in the United States comes from the fields of Mexico’s northern states. In our family we do not buy milk from the stores because we cannot afford it: an hour’s wage in Mexico will not buy a liter of milk — eight pesos or 35 cents. Sometimes we purchase milk from the “lechero” who comes by on his burro in the afternoon to dip out fresh milk into our pot. Once in a while we slaughter one of the chickens we raise in the back. But as for the majority of the Mexican people, bread, meat, fish, milk and eggs are a luxury.

Since 1975, the price of beans has risen 300 percent and that of tortillas 400 percent. Only the very privileged escape the gnawing hunger of malnutrition.

When we arrived in Cuernevaca in October, 1977, 1500 “textilleros” from four different mills had been on strike for more than a month against Burlington Mills. Their demands were traditional union demands: a minimum wage, reinstatement of workers who had been fired, retirement pensions, back-pay for days during the strike when there was no work. There were many problems with the strike, including a struggle against the leadership of the government-controlled union, the CTM (Mexican Confederation of Workers), who were more acquiescent to the desires of the company and the ruling government party, the PRI (Party of the Institutionalized Revolution). The only real hope of a truly democratic union is to form an independent union, a move which the Catholic Church, under the leadership of the Bishop of Cuernevaca, Mendez Arceo, solidly supports. After 102 days — betrayed by the union leadership and exhausted with hunger — the strikers went back to work. One week later the company fired 100 of the most “conscientized” leaders of the strike. With no recourse to gain back their jobs — no system of arbitration, unemployment compensation or welfare — these people face the same struggle to survive and support their families as the father in our family faced nine years ago.

Jose Obrero (a pseudonym), a friend of our father, was also fired by Burlington nine years ago. He told us about life in Mexico’s mills and the intricate web of control and dependence which the American companies have spun through the courts, police, political parties, unions and most of the church:

JOSE OBRERO: I’ve been a textile worker since I was 14 years old. When I began work, I had lots of hopes and ambitions. I started work because I had a friend who was able to get me a job. Naturally, I felt indebted to those who were good enough to give me work. But later I began to understand that it was part of the system that a person had to be thankful and grateful to the one who had given him work. The union leader was the one who gave us our jobs, and we had to support him when a labor election came up. But he was in cahoots with the company, since he was passing cut favors and giving people jobs only as the company allowed him to. When a union election was near, the factory would organize outings and suppers and drinking fests and would tell us who the people were who were best equipped to be labor union leaders. The leaders would call us and say, “Remember when I gave you that tarpaper so you could put it over your roof so it wouldn’t rain in? Well, now you have to give me a favor: work for the person the company designates as the new labor union leader and denounce anyone you hear opposes him.” So you see that the person who is elected as our leader is really in debt to the company. We wind up with two bosses, the owner of the factory and the labor union leader, if we complain to the union, they say, “If you don’t like the situation, you can leave. ”

The companies also have a grip on the churches. Where I began working outside Mexico City, all the factories had the names of saints. Every year on the Saint’s Day of the factory, there would be a big party, and there would be a Mass and the priest would give a very pretty sermon. The sermon basically said we should give thanks to the Lord because we had such a very good owner of the factory. We should be concerned with keeping the good relations between the workers and the owner. And we should renounce the Devil which came to the factories in the form of labor agitators and communists.

About nine years ago, some 70 of us began to meet together and discuss our situation and try to organize to change the system we were beginning to become aware of. We managed to get a lot of other workers thinking about what was going on, but because of this all 70 of us were fired and blacklisted so we couldn’t get work anywhere else in this _ city. We faced the alternative of either dying of hunger or leaving. The saddest thing for us was that the church organized a Mass of Thanksgiving to celebrate the fact that the so-called plot between the communists and the labor agitators had been broken.

I moved here to Cuernevaca and got a job working for Burlington Industries. But I found that here there was an even more refined system than in my hometown. To get a job here, you could not admit to having any previous contact with a labor union. They would hire you only if you were a campesino, a peasant or small artisan. So I told a white lie and said I had been an artisan.

Here I began to understand that it was considered a crime to speak about the rights that the law gives us. If there were any fringe benefits that we received it was because of the goodness and loyalty of the owner, not because of the rights the law gave us. For example, there were times when they would give us, free, a Coca-Cola or some old cardboard they had or some rags they didn’t need anymore. To show our appreciation for that we had to work a couple of hours a day extra without any pay.

Each year they celebrated the formation of the Labor Union. At the same time they would give us certificates in which they would show us their appreciation for our punctuality and our efforts at production. And with that we felt very happy. There were about 1,500 workers who were in the labor union, not counting the workers at the management level. Of the 1,500, only about 320 were considered permanent workers and accrued seniority. The others would work for six months or so and then Burlington would lay them off. Then they would be rehired, but only as new workers. So they might be working for 15 years, but never get past six months as a permanent worker; they would never accrue any seniority or any rights.

Burlington also used a system called variable workload. They took the workload set by the younger, stronger worker and placed it on the older worker, saying, “If you can produce this amount, then you can stay on as a permanent worker.” The young worker would work at a breakneck speed in order to be considered for permanent worker’s status. Everyone else would try to follow that rate, but naturally, after three or four years, a person would develop some difficulties with his health and begin to slow down from the strain. Then the owners would say, “Well, before you were a good worker, but now you’re beginning to get lazy. If you can’t work any faster, we’ll have to dismiss you and get a new person.”

Normally we had a half-hour lunch period in our eight-hour work shift. But then the company said they were in a crisis, so we had to give up our lunch period. We’d take our lunch in a brown bag and have to eat our sandwich or taco amidst all the dust and thread. Some people just stopped eating lunch at all, just kept working straight through without any food.

Because of my experience in my hometown, I started talking with the other workers about these conditions. We began to educate each other about what was going on through our underground papers and circulars, making them see the injustices we were suffering. The company became very concerned about what we were doing. They started investigating and identifying who we were. When they located me as being one of the key people of this group, they hired another person to provoke a fight with me in order to have a justification to fire me. The person who was supposed to provoke the fight with me was unsuccessful because I wouldn’t allow myself to be provoked. But since they had this all set up anyway, they just went ahead and wrote out the facts that I had been involved in a fight and fired me anyway. They started a petition among the workers asking that I be fired because I was a dangerous person, with a threat that anyone who refused to sign the petition would be dismissed from their work. The more permanent workers, as a fringe benefit, had the advantage of being able to purchase their home through an arrangement with the factory for financing. If they didn’t support the company, they could lose their work and if they lost their work, they would also lose their homes. Despite all this pressure, 42 workers were dismissed because they still refused to sign the petition.

The six of us who were the leaders were dismissed without any sort of compensation. We lost the savings we had within the company programs. We even lost our last week of salary. They blackballed us so we couldn’t get work in any other factory. They even arranged, through the government, to cut off any health services that, by law, we were entitled to.

The six of us felt that one of the major problems is the fact that the workers are especially ignorant of the law. If the worker knows enough to be able to apply the law in his favor, well then he is able to defend himself. But, sadly, in our own cases, we found that when we knocked on the door of the labor courts, the doors were all closed and there was no way of getting justice. Some of the workers in the union who came to my defense demanded that there should be an investigation of whether or not there really was a fight, and whether there was any basis for dismissing me. But the company told the court that the workers who testified on my behalf were all troublemakers, and the company had enough money to buy the justice it wanted from the government courts.

Everything was going against us: the government, the labor courts, the owners, the labor union, and the fear of our fellow workers. Fortunately, there was still one ally: the bishop here in Cuernevaca. Father Sergio and other priests here are very different from the priests in my hometown. He helped us economically and also morally, because he told us we weren’t alone. He said, “Don’t become demoralized in the experiences that you’ve had. Don’t just look at them and feel sorry for yourselves, but communicate them to others. ”

With that support, we organized here in Cuernevaca a school for labor union education. And now we’ve been working for nine years. The reaction of the owners has been very strong. They have put many workers on the blacklist. Some are in prison, accused of being guerrilla fighters, but really because they try to organize independent unions. There are now many small groups of workers studying, discussing issues and trying to organize. We continue to make progress and keep a strong spirit despite the extreme pressures from the company and the high sacrifice it demands from all of us. Nearly all the workers who have been dismissed have large families, so we have had to find ways to support ourselves as small artisans or small merchants or things like that. We try to help ourselves mutually and have tried to organize cooperatives. Unfortunately, what the cooperatives need is capital — and all we have are needs.

The tensions between workers and Burlington continued to intensify throughout the nine years after Jose Obrero was fired, culminating finally in the 102-day strike in late 1977, the first strike at the Burlington Mills since their opening. The official union continues to be a major obstacle for workers’ rights. In fact, for a year before the strike, the union leaders refused to hold an assembly of workers despite the constitutional requirement that meetings be held monthly. They were afraid they would be voted out and replaced by more militant workers. Only after pressure reached a breaking point did the union “tolerate” the demand for a strike, and then its official leaders quickly backed away, allowing the company to starve the workers into submission. Since the strike ended in December, 1977, over 400 activists have been fired by Burlington.

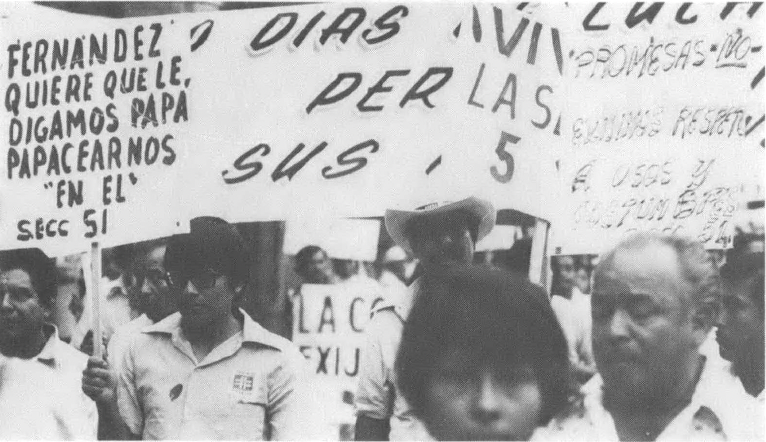

During the strike, workers and their families maintained a constant vigil in the central plaza of Cuernavaca, in front of the Governor’s palace. With banners and leaflets, they told bystanders and supporters of their struggle to break away from the government-regulated union and form their own syndicate. They collected money in cans at the plaza and canvassed neighborhoods to feed their families. The strikers also maintained around-the-clock picket lines at the four Burlington mills, prohibiting executives from entering the plants or hiring new workers. The story of their fight quickly spread throughout the state of Morelos as a constant stream of supporters from other factories and from various political groups joined them at the town square and then returned home to tell others. A people’s theatre group, Los Mascarones, toured from barrio to barrio with an entire repertoire of songs and skits portraying the oppression of Mexican “textilleros” (textile workers) by Burlington Industries.

The Church was the strongest and most unifying supporter of the strike. In his sermons at the Cathedral’s daily mass, the Bishop of Cuernavaca, Sergio Mendez Arceo, constantly advocated the liberation of the poor from their oppressors. He even called for a ban on all services usually held in the factories on the Day of the Virgin of Guadalupe (December 12). In their place, he held a special mass for the textilleros and their families in the famous Cathedral of Cuernavaca. Local priests also helped build solidarity among workers and conducted “reflection” groups on the Gospel of Liberation and the strike. Their leadership was instrumental in establishing the labor education school mentioned by Jose Obrero, which became a center of discussion and helped many workers understand their legal rights for the first time.

The two largest demonstrations of workers occurred in November, 1977, during the third month of the strike. The first was a combined protest by 3,000 workers and the staff of a government-sponsored hospital set up the previous year “for the people.” When the staff had tried to expand their services to establish neighborhood clinics and confront the housing, food, water and workplace conditions behind the medical problems of their patients, the government threatened to close the main hospital. At that point, striking workers joined the hospital staff in a huge march from the gates of one of the Burlington plants to the city’s main street and on to the Governor’s palace. A few days later, the “people’s” hospital was closed.

The second large demonstration occurred on November 20, the date set aside to commemorate the Mexican Revolution of 1910. As the date approached, Army officers told the workers in the central plaza to end their vigil and take down their banners so the Revolutionary Parade could pass by the Governor’s palace. The strikers refused to move. True, their numbers and militancy were dwindling as food grew scarce and “los charros” (betrayers) argued for a return to work. But for many textilleros, the fight against Burlington was the same as that of their revolutionary hero, Emiliano Zapata. They pledged to remain in the plaza as an expression of solidarity with their past. The evening after the Army ordered them to leave, more than 200 workers and their families and supporters camped in the plaza. Fear filled the air as people waited for the military action which inevitably follows such acts of rebellion. The theatre group, Los Mascarones, arrived with guitars and movement songs. People huddled together on the cold plaza ground, singing, keeping each other awake, laughing. Late in the evening, three truckloads of soldiers arrived at the central plaza. Unloading quickly, the unarmed men went through a series of exercises, marched around the singing crowd, loaded back into the trucks and departed. No one knew if the soldiers would return and move into action. The demonstrators waited through the next day and into the night, but there were no other signs of confrontation.

The day celebrating the Revolution arrived. Thousands of people filled the streets and central plaza to watch the Revolutionary Parade go by. In front of the Governor’s palace, unmoved, stood the textilleros with a huge new banner stretched in front of them. “VENCEREMOS,” it read. “We shall overcome.”

Burlington Industries is not an isolated example of foreign companies exploiting Mexican workers. Nearly 50 percent of the shares of the 290 largest corporations in Mexico are controlled by transnational companies; the percentage of the industrial workforce employed by the capital-intensive transnationals has doubled over a 10-year period to more than 16 percent. The increasing integration of the Mexican economy into the international capitalist system means that the bread and the labor of the Mexican people is more and more in the hands of foreign banks and corporations.

In August, 1976, under pressure from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Mexico devalued its peso for the first time in 22 years. With inflation running as high as 20 percent and unemployment approaching 60 percent, the bankers in New York, London and Paris were unhappy. Mexico was in debt $28 billion, half of this amount owed to private banks in the US such as Chase Manhattan, a prime lender to the World Bank.

In 1973 the president of Chase Manhattan Bank, David Rockefeller, had helped to found the Trilateral Commission, an organization of US, West European and Japanese capitalists united to manage “a single world economy in addition to managing international economic relations among countries.” President Carter, as well as his Vice-President, National Security Advisor, the Secretaries of State, Treasury and Defense, and the Ambassador to the UN, are all members of this elite monitor ofcapitalist interests. The Trilateral Commission is currently proposing that international public banks, such as the IMF, implement conditions of austerity in their loans to Latin American countries. This has been done in Chile, Argentina, Peru, Jamaica — and, most recently, in Mexico. According to David Rockefeller, the extension of credit to less developed countries should be “subject to rigorous conditions that assure domestic policies which promote efficient adjustment.”

The immediate effect of the devaluation of the peso in Mexico was a loss of 50 percent of its value: food prices doubled without a corresponding increase in wages. Four months later the former Governor of the World Bank and the IMF in Mexico, Jose Lopez Portillo, took office as President of Mexico and announced a new SI.2 billion loan from the IMF. The loan came with certain conditions of austerity: a cut in government spending in the public sector, a limit to the creation of new jobs, a 10 percent ceiling on wage increases, prices of basic commodities like food left free to rise. While real income for workers declines, the number of strikes — with or without official union sanction — continues to increase. In the first three months of 1978, there were 427 strikes, 47 percent more than in the same period in 1976.

The prospects for the future are not encouraging. The discovery of oil and natural gas deposits in the southeastern states of Mexico in 1973 will alleviate but not resolve the crisis. A fourth of the country’s $4 billion annual exports now comes from petroleum sales. The US, which imports 70 percent of this oil and gas and which looks to Mexico as an alternative to Arab dependence, is not likely to pressure the government to enact new measures to help the growing number of poor people. In the next 20 years, the population of Mexico will double to 120 million. Mexico City will shelter more than 32 million inhabitants — one-half the current population of Mexico — by the year 2000. During the years 1971-1974 the caloric consumption of the peasants declined by 20 percent, and they are getting hungrier; 5.5 million children are malnourished and 200,000 die each year from malnutrition and disease. For every 1,000 children born in Mexico this year, 65 will die before age one. The economics of austerity are in fact implementing a policy of starvation among the Mexican people.

Not far from our colonia there is a district called “La Estacion,” where more than 500 families have come to live as squatters over the past 30 years. Here, amidst the huge eucalyptus trees which overshadow the abandoned railroad station and the outlying area, the people have built “casas de carton” — cardboard shacks constructed from trees, old shipping crates, scrap metal, and sometimes stone gathered from the rocky soil. Here in these “casitas” one room often serves as dining room, bedroom and kitchen where parents and children alike eat, sleep and prepare their meals. Many of them have had electricity now for some years; all of them lack water and toilets.

Until a year ago, there was no water in the entire village. People either had to go to the market each day to buy water and carry it home, or else risk drinking contaminated water. Then, as people became more organized, a popular assembly was formed which meets every Sunday afternoon to discuss the problems of the community: water was a most immediate need. Within a matter of weeks the community began to construct its own system of water. Soon three outlets were established. Still, the water was rationed by the government and was available only at night. Long lines of barefoot children, grandmothers and mothers nursing their babies began to form during the night and the early morning hours, all of them laden with wooden poles slung across their shoulders. All variety of buckets and paint cans hang from ropes tied to their poles. From the outlets they must carry the water — sometimes more than 70 pounds — long distances to their shacks to use for cooking, washing and, of course, to drink.

Some years ago, not far from here, a man named Ruben Jaramillo attempted to lead his fellow squatters in just such a venture to build their own colonia, their own neighborhood. On March 31, 1973, more than 15,000 squatters occupied lands the government seized for tax delinquency and then left abandoned. They pooled their incomes — $1 to $3 a day — and built cooperative stores, bakeries and slaughterhouses, built schools, laid sewer pipes with volunteer labor, and banned alcohol from the colonia. On September 28, 1973 — less than six months later — 2,000 soldiers and 100 police attacked the settlement in the predawn hours, shooting Ruben Jaramillo, his pregnant wife and their two children. But the people continue.

The South Goes North

In 1923, the Burlington, North Carolina, Chamber of Commerce offered to underwrite the expense of a new factory if an aggressive young mill owner named J. Spencer Love would move his operations to their city. For forty years, until his death in 1962, Love acquired, merged, and built new mills—often with other people’s money—until he created the largest textile company in the world, Burlington Industries.

In the 1930s, he gained reknown for the “Wooden Walls of Burlington” because he left one temporary wall in new plants, making it easier to expand. In 1944, he opened his first mill outside the United States—the Textiles Morelos complex in Cuernavaca, Mexico. Following World War II, Burlington continued to expand, growing from 45 plants and $93 million in sales in 1944 to 119 plants and $1 billion in sales in 1962, with mills in Mexico, Canada, Germany, Colombia, South Africa, France, and England.

To build that fast required an immense influx of new capital. Love, the Harvard-educated son of a Gastonia, N.C. family, moved Burlington’s headquarters to New York to be closer to the money sources. He hired business school graduates and professional managers, and put a number of his Wall Street associates on his board of directors. The money rolled in, and Love dazzled brokers and bankers by getting a greater return on their investment than other textile companies could.

Since his death, Love’s company has continued to lead the industry in new management procedures, technological innovations, public relations techniques, and financial and inventory controls. It is the kind of company Wall Street loves. Unlike others in the field —including number 2 in the industry, J.P. Stevens & Co. — Burlington has little old-line family influence or ideological preoccupations to distract its succession of professional managers from squeezing the most from the least. It annually invests three times as much on modernization and expansion as Stevens does, and nets twice the profits as Stevens with only 50 percent more workers. With relentless precision, it has streamlined overhead costs, cut out less profitable product lines, diversified into furniture and other businesses, and modernized those plants with the brightest future. According to Horace Jones, former Burlington chairman, “The restructuring, although painful and difficult for the company, has resulted in opportunities for increases in productivity and the establishment of a keen and aggressive posture in our highly competitive industry.”

The restructuring has been most painful to the 20,000 Burlington workers who lost their jobs, most of them in North Carolina where half the company’s mills are still located. From 1973 to 1978, it increased its sales from $2.5 billion to $2.9 billion while closing 32 plants and reducing its work force from 88,000 to 66,000 people. Burlington often told its workers that they were losing their jobs because of the 1974- 75 recession or because of increases in foreign imports. “We are seeing the massive market disruption in the U.S. textile and apparel industries because of mushrooming growth of imports which has caused extensive damage to member companies and their employees,” Burlington explained in a full-page ad in Carolina newspapers. But foreign production is actually a growing part of Burlington’s own business. (In 1976, it admitted it had paid “about $300,000” in bribes to foreign officials in the previous five years “to continue normal operations.”) Sales from foreign plants contributed $282 million in 1978 and the company’s foreign work force of 8,000 has remained relatively stable while domestic employment declines. Last year, while Burlington closed seven plants in the South, it spent another $30 million to expand its new operations in wage-depressed Ireland. In the ten years from 1969 to 1978, Burlington closed more than 30 mills in the South and spent over $1 billion to further automate those remaining. People lose jobs not simply because of foreign production, but because of Burlington’s commitment to replace workers with machines. As company spokesman Dick Byrd says, “We’re using new technology and faster equipment to do the same volume of work with fewer people.”

Meanwhile, Burlington tries to preserve the paternalistic idea that its policies are in the best interests of its employees. “The Company that keeps ahead is the one that can predict with some degree of accuracy where . . . changes will occur, and swing quickly to meet them,” executive vice president Charles McLendon recently wrote in the Employees’ newsletter. “For us, in some instances, this has meant closing plants or cutting back certain operations. In others, it has meant expansion, or conversion of facilities from one product to another. . . . These are hard decisions, but they must be made to protect the best interests of the total Company, to strengthen our overall position, to fulfill our obligations to shareholders and to improve job security for the great bulk of our employees.”

Burlington can be expected to continue to use its sharp-pencil managers and computers to make its operations “fulfill our obligations to shareholders.” The profit margins are slim in textiles, and even though Burlington is number one, it does less than seven percent of the industry’s business. It can’t manipulate prices and profits like a General Motors or Kellogg or US Steel can in industries controlled by three or four producers. There are 5000 textile companies in the U.S., with 6000 plants. So Burlington tries to use its access to big money, its experience in ruthless inventory controls and highly automated facilities to overcome problems that might bankrupt others in the field. Some observers have suggested that Burlington might like to see some of its competitors driven out of business by such things as the cost of meeting EPA, OSHA or minimum wage standards. (Love took the unique position of favoring the rise in minimum wage to $1 in 1960, shocking many textile owners but further establishing his company’s “progressive” image. More recently, Burlington has not joined the rest of the industry in denying that OSHA’s new cotton dust standard can be met within four years, even though it will require substantial investments in new machinery.) With fewer, bigger competitors the industry could begin to operate more like those dominated by a handful of producers. Instead of small profit margins, it could boost profits artificially and make greater profits off fewer units sold. Such a trend would be consistent with Burlington’s reliance on faster machines and fewer workers.

Whatever the future holds for Burlington, it still has some of the most sophisticated corporate managers at its helm, men with extensive multinational financial and governmental experience who are far removed from the stereotypical Southern mill owner. Among Burlington’s board of directors are:

George W. Ball, senior partner of the Wall Street brokerage firm, Lehman Brothers; also a director of American Metal Climax (AMAX); former Under Secretary of State, 1961-66, US representative to UN, 1968, and international troubleshooter for Kennedy and Johnson.

Ernesta D. Ballard, pres, of Pennsylvania Historical Society.

Joseph W. Barr, partner of J & J Co., real estate developers; trustee, Committee for Econ. Development and Georgetown Univ.; dir., 3M Co., etc.; former Under Sec. of Treasury, 1965-68, Treasury Secretary, ’68-69, and pres./chrm., American Security & Trust Co., ’69-74.

William S. Boothby, Jr., chrm., Blythe Eastman Dillon & Co., Wail Street brokers; active Republican; dir. of ten corporations, including Getty Oil, Sperry Rand, Georgia-Pacific and Insurance Co. of No. Amer.

Alexander Calder, Jr., chrm. of Union Camp; dir. of Bank of New York, Seaboard Coastline, Tri-Continental Corp., and Ingersoll-Rand.

William T. French, retired chrm. of First National Stores; member, Foreign Policy Assoc.; dir., Pillsbury Co., Warnaco, Inc., SuCrest Corp.

Frank S. Jones, Ford Professor of Urban Affairs at M.I.T., Boston.

Horace C. Jones, Burlington’s finance comm, chrm.; dir., Union Carbide, Union Camp, Wachovia Corp, and Provident Mutual Life Ins.

Harry W. Knight, dir., Agricon, Inc., Insurance Co. of No. America, Waldorf-Astoria, Shearson-Hayden Mutual Funds, etc.; trustee, Comm. for Economic Development; mem., Foreign Policy Assoc., UN Assoc.

John W. McKinley, president of Texaco, Inc.

Hans Robert Schwarzenbach, Swiss textile owner and investor.

John W. Simmons, chrm., Morton-Norwich Products.

— Southern Exposure editors

Tags

Scott Wright

Scott Wright and Martha Clark spent several weeks in Mexico in late 1977 during the strike at Burlington Mills. They have written about their experiences in The Catholic Worker and are involved in other educational programs with the textile workers in Cuernevaca. (1979)

Martha Clark

Scott Wright and Martha Clark spent several weeks in Mexico in late 1977 during the strike at Burlington Mills. They have written about their experiences in The Catholic Worker and are involved in other educational programs with the textile workers in Cuernevaca. (1979)