This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 1, "America's Best Music and More..." Find more from that issue here.

It was only a few years ago that Rolling Stone, in what was doubtlessly conceived to be a benevolent gesture, alerted its readers to the existence of a band of “long-haired good old boys” called the Allman Brothers who could “play up a storm.” A week later a letter from Athens, Georgia, was published responding in effect, “Sho’ was nice of you San Francisco fellers to condescend to mention the Allman Brothers. Wonder how long it’ll take you to realize that the South is now producing the best damn rock and roll in the country?”

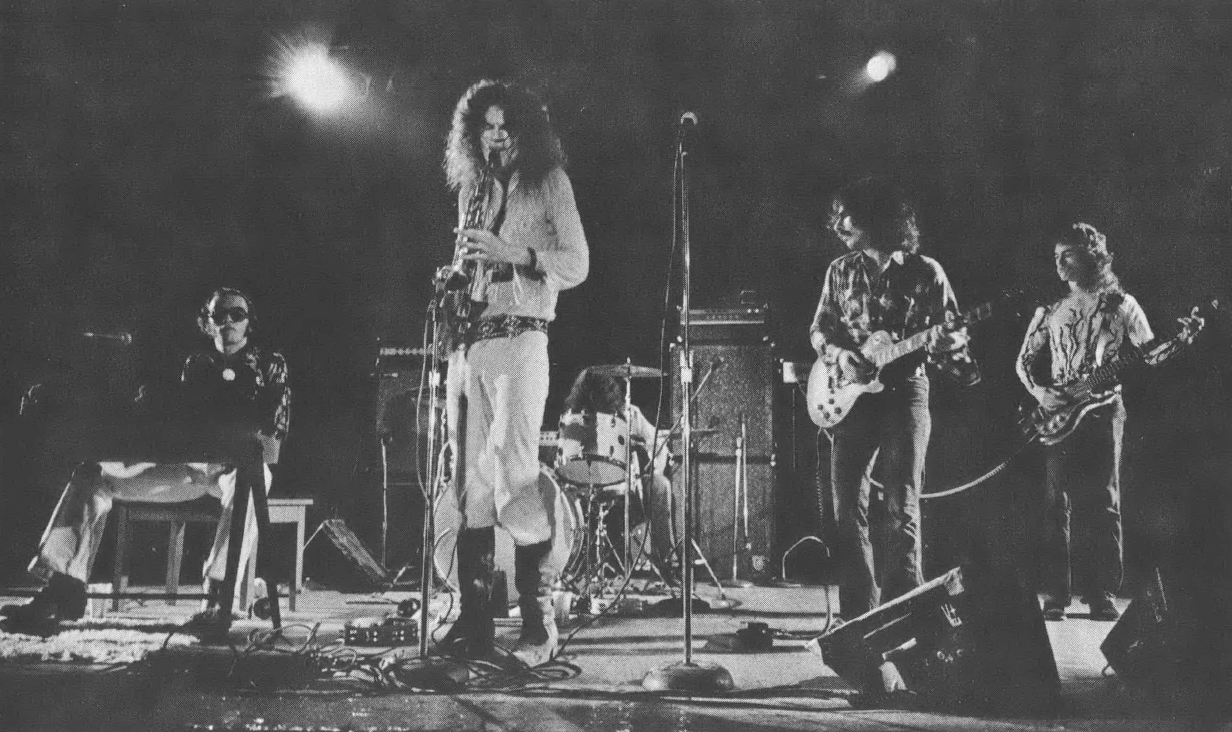

Seven o’clock on a Thursday night in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. College students stroll along the local main drag, Franklin Street, past picturesque restaurants, colonial-facade banks, and charming boutiques. For someone used to big-city drabness it’s all just a little too quaint. Still, it’s a relaxed, pleasant atmosphere. In Town Hall, the largest beer-and-boogie emporium in Chapel Hill, a dozen or so students and street people are eating sandwiches from the delicatessen and picking out good seats close to the stage. The Steve Ball Band is playing tonight.

The South never really left the mainstream of rock music, of course. From Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis to Janis Joplin, Southern musicians continually pumped infectious vitality into periodically dull popular music. Truly good musicians in England and in California recognized this and never ceased to pay verbal (though seldom financial) homage to the bluesmasters, country pickers, and early hard-rockers that had influenced them. But as rock entered the halcyon days of the mid-sixties, the South began to be ignored and even berated by the emerging hip-capitalist music hierarchy. It was hard even to arrange a concert in the South, much less convince smug long-haired executives that there were fine musicians putting together all the old elements of rock in new ways, and indeed, introducing material previously undreamt of.

The Steve Ball Band is beginning to set up their mountains of sound equipment. They sip beers and chat with “regulars”—the people who follow them from gig to gig. Like their friends, the band members are North Carolina Piedmont freaks. They wear work-shirts, old-jeans, and shitkicker boots while their hair has been studiously protected from the ravages of “stylists.” All told, they look pretty much like any road-crew you see working on the Interstate: mellow, down-home, and semi-wasted.

Southern rockers were building their music from two of the strongest American musical traditions: blues and country & western. From C&W they learned the use of the steel and slide guitars; from blues, they learned how to make old telecaster electric guitars sing and wail. Country music taught them sentiment (sometimes verging on sentimentality) and a longing for rural life. The blues balanced this with its urban realism and frank good humor. Both traditions supplied a strong spirituality that was reinforced by acid mysticism. The southern chauvinism that is up front in country music and sometimes apparent in the blues combined with a cynical sort of populism to give southern rock its ambivalent political tinge. Few songs are blatantly “revolutionary” or “protest” oriented, but almost all imply a bi-racial class consciousness both of oppression and immense inner strength.

Strange combinations these, and seemingly untenable. Yet through the lean years of the Sixties, the musicians and their constituency synthesized their forebearers’ experience and their own obscure visions into a music and a sense of community that provided alternatives to the middle-of-the-road drivel and Bold New South bullshit that were infiltrating and destroying the South’s identity.

By the time the equipment is set up and instruments are tuned, Town Hall is packed. Most of the audience are UNC students, talking about tomorrow’s exam and last week’s hashish with equal seriousness. A good many in the crowd are members of what might be called “the new working class’’—long-haired construction workers and stoned waitresses, the nearest rock-and-roll equivalent to the honky-tonk crowds of Nashville and the blues devotees of Chicago’s South Side. There are even a few glitter freaks, their cheesy decadence looked upon with aloof amusement by most of the crowd. David Bowie has a long way to go down here.

The club owner paces back and forth between the stage and bar, pausing occasionally to speak to an employee or regular customer. He looks like somebody who is very aware of the importance of his job. Approaching the band’s sound-man, he asks several questions and apparently gets the right response since he claps the man on the back and moves on. The sound-man looks over at the woman working with him and shakes his head. They both smile.

The fragile, tentative youth communities that sprang up in places like Tallahassee, Virginia Beach, New Orleans, and, of course, Atlanta, all revolved around the music. These were the days of free concerts in the park, hanging out on the street, and jamming all night. Journalist Hunter Thompson caught that strange exuberant magic when he wrote “In those days you could go in any direction at any hour of the day or night in perfect assurance of running into people just as crazy and twisted as you were.” It was a time of such boundless possibilities as seems almost incredible to us now, a scant five years later, but those times were real and the music caught it and pushed us further. The Allman Brothers, already emerging as the leader of the musical movement, opened their second album, Idlewild South, with the lines, “People, can you feel it, love is everywhere.”

But already there were tensions developing as inner contradictions surfaced and societal pressure intensified. In the community itself the use of hard drugs became a convenient way out of the dreary cycle of police harassment, roach-filled apartments, bad food, and general paranoia that increased as America began to change its view of freaks from harmless oddballs to dangerous menaces. Life’s emphasis slowly shifted from a loving celebration to a grim determination to survive. The Allman Brothers’ “Midnight Rider” became the Southern freak’s anthem.

“I got one more silver dollar. . .

And the road goes on forever.

But I’m not gonna let ’em catch me no,

Not gonna let ’em catch the Midnight Rider.”

A bearded guy in a lumberjack shirt is loudly demanding that the band, which hasn’t even tuned

up yet, play “Statesboro Blues.’’ When this fails to get a response he sings the opening lines himself. “Wake up, mama, turn your lamp down low!’’ Everybody ignores him, including his embarrassed woman friend. “Wake up, Mama!’’ He shouts and slowly slides from his chair to the floor, passed out. As he’s more or less dragged to the door, someone murmurs, “I wonder where he scored those downs.’’

At about the same time, success was finally beginning to dawn for the Allman Brothers. The seemingly endless round of touring was building an audience outside the South, both among promoters (Bill Graham said they were his favorite band) and the public at large. But there was a large price tag attached to national approval of their excellent music. It came in the form of frayed nerves, expensive cocaine habits, and deteriorating personal relationships. Finally, the long road

seemed to come to an abrupt end when the premier slide-guitar player and focal point of the band, Duane Allman, was killed in a motorcycle wreck in Macon, Georgia. His death was followed in less than a year by the loss of bassist Berry Oakley in a similar accident only a few blocks from the site of Duane’s crash. In a curious way, the low-point of southern freak culture paralleled the near shattering of its most articulate voice.

Both survived. They survived the same way the sharecroppers and the mountaineers had done it: by pulling back to the land and their extended families and holding on to what they needed. The visions of sweeping change and the joys of stardom were gone, but the community and music remained open to growth and development. Out of the increasingly stable, far-flung communities emerged bands that combined the soaring guitar lines and solid rhythms of the Allmans with their own distinctive styles. The Marshall Tucker Band brought their music out of the small club circuit around Spartanburg, South Carolina, and into national prominence with a fine debut album. Wet Willie, Hydra, Mose Jones, and Lynyrd Skynyrd had long been mainstays in Atlanta, polishing and refining their material, until they got their breaks. Cowboy sprang from the central Florida tourist boom towns, getting deserved acclaim as Gregg Allman’s back-up band on his solo tour. Commander Cody and his Lost Planet Airmen got their initial recognition in Berkeley and Ann Arbor, but they never forgot that their rockabilly music was as Southern as lead singer Billy C. Farlow’s Decatur, Alabama accent.

It became a truism that every milltown and university city had its own fine band, playing its heart out six nights a week in cramped dance clubs, dodging beer bottles and answering requests for old favorites, all the while dreaming of the day when they would be summoned by Phil Walden or Al Kooper to record their album in Macon or Atlanta.

The band has opened with an original song, then moved into an incredibly driving version of Aretha Franklin’s “Chain of Fools.’’ They receive scattered applause which the drummer acknowledges with a “thank you” and a nod. “That first song is gonna be on our album, which we’re gonna have to re-cut down in Atlanta soon’s we get a chance.’’ He looks tiredly at the bass player and organist, who laugh and light cigarettes. The initial excitement of a recording contract fades after long hours in the studio and the dawning realization that not all the petty rip-offs and two-faced bullshit are confined to local managers and club owners.

Southern musicians are presently receiving their greatest encouragement from Capricorn Records and Al Kooper’s Sound of the South. Kooper, a musician who won great acclaim for his mid-sixties work with Mike Bloomfield, Steve Stills, and Bob Dylan, now lives in Atlanta. A veteran of many artist-record company battles himself, he goes out of his way to give the artists on his label both musical freedom and financial stability. Phil Walden, the guiding light of the Allman’s label, Capricorn, is also generally known for his dedication to the southern sound. Of course, it is one thing to love the music and quite another to gain it popular acclaim through the devious, brutalizing world of media conglomerates. It’s doubtful if anyone can do it successfully and emerge with personal reputation unscathed. Yet there does seem to be a qualitative difference between the artist’s lot at Capricorn or Sounds of the South and the New York or Los Angeles studios.

The band is into an extended jam now, lead singer Steve Ball hunched over his harmonica taking the lead while the bassist rocks back and forth on his heels laying down a solid rhythm. A black couple is doing the Bump, a dance that entails partners, yes, bumping hips, knees, and butts. It's probably what the John Birch Society had in mind when they warned of the menace of Negro dancing. Integrated schooling is, of course, in dire straits. Mixed housing seems light years away. But as the band and the dancers respond to each other's energy, it’s plain to see that at least in its music, the South’s blacks and whites interact with respect, rather than fear and dislike.

Today, southern rock probably is, as the disgruntled Rolling Stone reader insisted, the most alive popular music being played. It needs neither ghoulish stage props nor a contrived decadence to be appealing. Southern musicians get on stage and give. They finally care little if “outsider” audiences understand. They have learned from vast, varied traditions that have little to do with the taste-maker’s analysis of what will be pop music’s very next phase. When Janis Joplin is singing or Richard Betts is picking they are in that timeless region where the past’s burdens are freed by the vision of freedom, now and forever. The South has learned from suffering, and through its music, is making a gift of its knowledge. It can be joyfully taken, or, as so many times in the past, rejected. No matter, in the steamy rock clubs and on sunny back porches, the music will go on.

A long night is nearly over. The people who came for sexual conquest have left, as have those who came to display their outre finery. The only ones left are those truly into the music or too drunk to walk. The band is cooking, as they are starting to say again, with gas. The organist is making his church-like chords act as a foundation for the guitarist’s leaping screaming notes. Ah, who can describe it? One need only look—the closed eyes and thrown-back heads, hands balled into fists, clutching at the music, never wanting it to stop. Finally it is over, and there comes that brief moment when the band and the audience gaze at each other in total communication. It only lasts a second, but that’s all that’s needed. The bass man says quietly, “Good night.’’ It’s the end of another gig for the Steve Ball Band and they and the audience walk out into the cool air of a pre-dawn North Carolina morning.

Tags

Steve Cummings

Steve Cummings, a native of Florida, is a cultural historian and a member of the staff of the Institute of Southern Studies. A former organizer of migrant farm workers in Florida, Mr. Cummings now lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he handles promotional chores for Southern Exposure. (1974)