This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

The history of Birmingham and its working people is unique to the South. Termed the “Magic City” for its miraculous growth in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, Birmingham underwent industrial development that sharply deviated from the South's agrarian norm. Yet its racial attitudes, its treatment of laborers and its corporate practices were distinctly Southern. Despite the injustice and suffering endured by the working people who came to Birmingham, the rise of heavy industry where once only pine trees and com fields stood is in many ways remarkable - and is worth recalling today, as the iron mines are sealed shut, the rolling mills quieted and most of the blast furnaces shut down.

A key turning point in the Birmingham District’s development was the advent of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) which, in the 1880s and 1890s, successfully merged several coal and iron companies. At three times the size of its largest competitor, the Sloss Iron Company, TCI produced half the District’s coal and iron. In 1907, United States Steel acquired TCI through a complicated series of stock manipulations that still raises suspicions of major antitrust violations. With this purchase, U.S. Steel eliminated its Southern competition and doubled its already vast supplies of raw materials. Pictured here are the owners and management of the Woodward Iron Company, a TCI competitor, at the groundbreaking of a new mine, c. 1910.

Many of the early skilled workers in Birmingham were immigrants — primarily from Great Britain, France and Germany — who were attracted by jobs for men who knew how to build furnaces, make iron and mine coal. Later they were joined by Poles, Prussians and Italians who, around the turn of the century, assumed somewhat less skilled jobs. Puddlers, such as those pictured here in Gate City, Alabama, in 1895, stirred molten iron in 500- to 600-pound lots. Skilled workers naturally led the way in wages. The few furnace masters received $4 to $5 per day, and some got bonuses for iron produced over a quota. Common laborers around the furnaces, including iron carriers, were paid $1.20 per day in 1900. Iron ore miners, the vast majority of whom were black, were paid about the same as common laborers, about $1 per day. As in Northern industries, workers put in 12-hour shifts, six days a week, with furnace men working a double shift of 24 straight hours every other Sunday. Wages in Birmingham, however, were 25 to 40 percent lower than in the North.

Counties in the Birmingham District leased their convicts to coal mines, and a fee system developed by many county sheriffs made justice impossible. Under this system, the sheriff derived his salary from fees charged to the prisoner upon his conviction. If convicted and unable to pay his fines, sheriffs fees and court costs, the prisoner was sentenced to hard labor to pay off the charges. Obviously, this system provided a powerful incentive to the sheriff and his deputies to arrest and convict men for any possible offenses. Consequently, stockades at coal mines and gangs of shackled prisoners working on Birmingham roads were a common sight.

Pratt Consolidated Coal Company’s Banner Shift prison epitomized the abuses of the convict lease system. Half the prisoners worked from five a.m. to eight p.m. in seams of coal 36 inches high. In 1911, 123 black convicts died in an explosion; 30 percent of those killed were serving sentences of 20 days or less. Others, burned or maimed in the disaster, received no medical attention. The usual punishment at Banner was a severe whipping; however, the “dog house,” a standing coffin-like box sealed except for a small hole at nose level was also used. Standing in the hot summer sun or the cold of winter, 400 prisoners spent 4,000 hours in this box in 1925. The 360 convicts at TCI’s Pratt No. 12 prison slept in six sleeping rooms, one of which is pictured here.

The leasing of state prisoners to private individuals began in 1846 when Alabama leased convicts to plantation owners in order to avoid the expense of operating a penitentiary. By 1872, railroads and coal mines in the District dominated the bidding for the prisoners. Coal mines paid $16 a month, plus room and board, in 1898 for the unrestrained use of convict labor. Over 80 percent of the prisoners were indigent, mostly illiterate, blacks charged with vagrancy or other Jim Crow-related offenses. As the price for convict labor climbed, these leases proved highly profitable to the state treasury. Between 1922 and 1926, 1,150 convict miners produced 1.5 million tons of coal at an estimated market value of $3.5 million. Despite scandals involving bribery, embezzlement and mistreatment of prisoners, the system was not abolished until 1926.

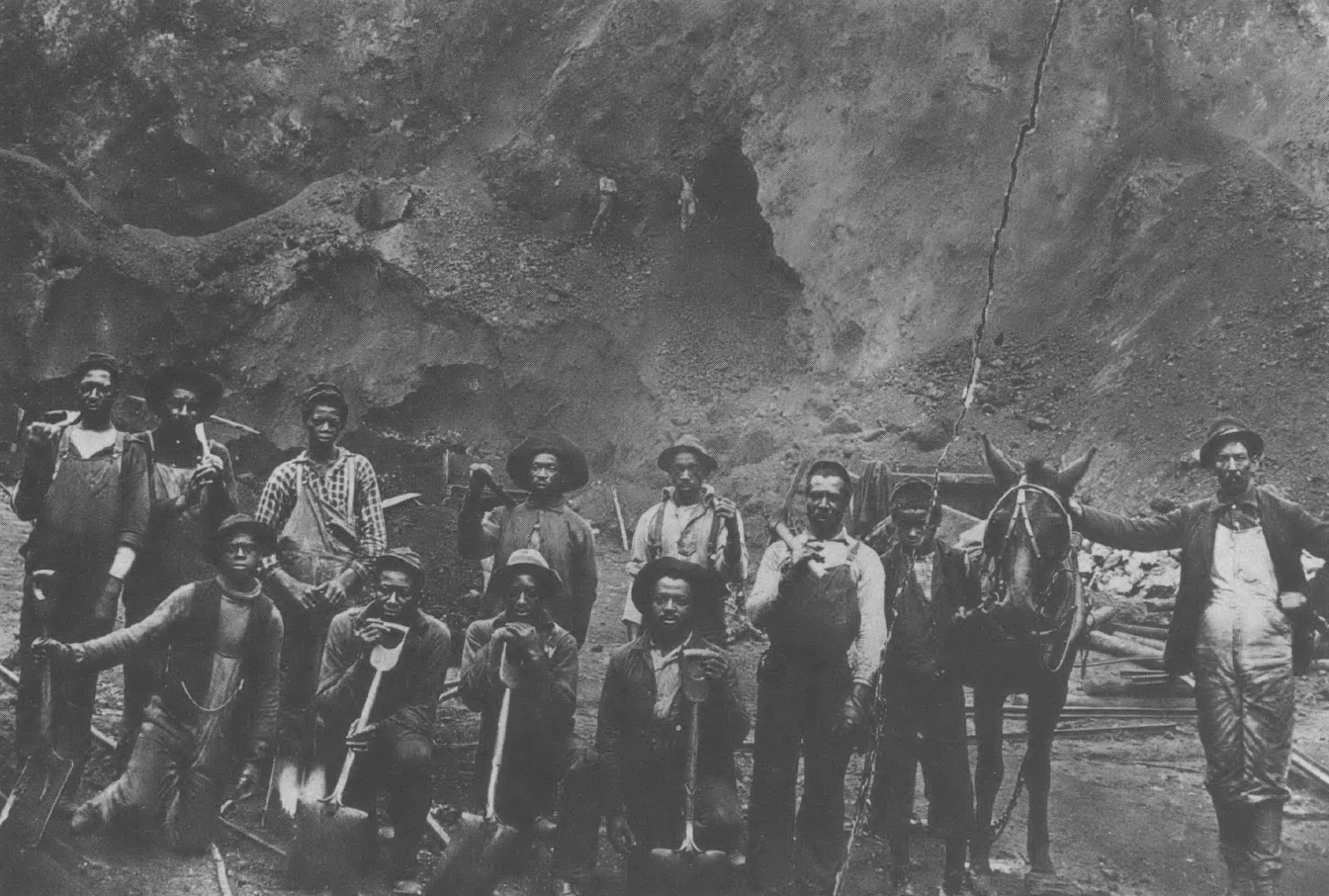

Approximately 60 percent of Birmingham’s work force was black. Blacks dominated iron ore mining, and about 65 percent of the District’s coal miners were black. Whether facing the intense heat and toxic gases of the coke ovens, loading coal and iron by hand, or digging foundations with picks and shovels, blacks were relegated to the bottom of the industrial hierarchy. Of all the jobs held by blacks, iron carriers had perhaps the most physically demanding and crucial job. After the iron cooled in long sand molds, it was broken apart and loaded into railroad cars. Breaking the separate molds with sledge hammers and crowbars, the iron carriers had to work quickly so the sand bed could be prepared for the next cast. In the Jim Crow days of early Birmingham’s industry, blacks rarely operated machinery and almost never filled supervisory positions. This group of black laborers stands at an iron ore outcrop owned by the TCI Company.

Coal mining was Birmingham’s most dangerous occupation. Roughly half of all mining fatalities were caused by roof cave-ins. In this photo of TCI’s Pratt No. 3, note the absence of any roof supports as well as the open flame miner’s lamp. Even as late as the 1950s, systems for supporting the roof consisted of nothing more than wooden posts, and often these were not used. One-third of all deaths resulted from sudden explosions of methane gas in mine shafts. Birmingham coal companies did little to prevent explosions; forced ventilation of the mines was minimal, and miners wore lamps with open flames as late as the 1930s.

From the time of Birmingham’s earliest industries in the 1870s, companies built tracts of houses which they rented to their workers. Along with these houses came a commissary where the company sold mining supplies, including dynamite, fuses, oil and tools, as well as food and household items. Company towns, originally intended to attract workers to remote sites, proved highly profitable; firms such as the Sloss Iron Company maintained large villages for workers adjacent to the furnaces near downtown Birmingham. During the Panic of 1893, as much as 40 percent of TCI’s profits came from house rents and store sales. TCI’s subsequent refusal to lower rents and prices angered many coal miners and helped precipitate the strike of 1894. Even during the relatively untroubled year of 1899, TCI’s mercantile sales of $2 million provided one-third of the company’s profits. The names of many of these company towns — Fairfield, Ensley, Muscoda, Ishkooda — still appear on Birmingham area maps. Here a TCI sheriff stands guard on Red Mountain, overlooking a company town in the 1930s — perhaps Muscoda or Ishkooda.

In 1894, over 80 percent of the non-convict miners formed the United Mineworkers of Alabama and struck rather than accept a 30 percent wage cut. The companies responded by stepping up production at convict mines; evicting the miners from company-owned houses; and importing strikebreakers, the vast majority of whom were black. After four months of guerrilla war, the strike was defeated. Most remarkable about the strike, however, was that blacks and whites, despite company efforts to divide them, remained cohesive and fought as they worked — side by side. Another organizing attempt was not made until 1908, when a strike was again defeated, this time when operators successfully aroused public sentiment against the strike by exploiting racial prejudice. Citing the danger of “8 or 9 thousand niggers idle in the State of Alabama,” Governor B.B. Comer ordered state troops to cut down the tents in which the striking miners were camped. The mines were not unionized until 1934, when the UMWA, riding a crest of pro-union fervor, organized almost every coal miner in the Birmingham District, while the Steel Workers Organizing Committee organized most of the steel works.

Tags

Mike Williams

Mike Williams and Mitch Menzer are graduates of Amherst College in American Studies. Williams, a native of Tuscaloosa, is currently a student at the University of Alabama. Their research into the history of Birmingham was supported by a Youthgrant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The photographs shown here are part of “Images of Work,” a larger exhibit of historic photographs of industrial Birmingham which will be shown in and around Birmingham. (1981)

Mitch Menzer

Mike Williams and Mitch Menzer are graduates of Amherst College in American Studies. Williams, a native of Tuscaloosa, is currently a student at the University of Alabama. Their research into the history of Birmingham was supported by a Youthgrant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The photographs shown here are part of “Images of Work,” a larger exhibit of historic photographs of industrial Birmingham which will be shown in and around Birmingham. (1981)