This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

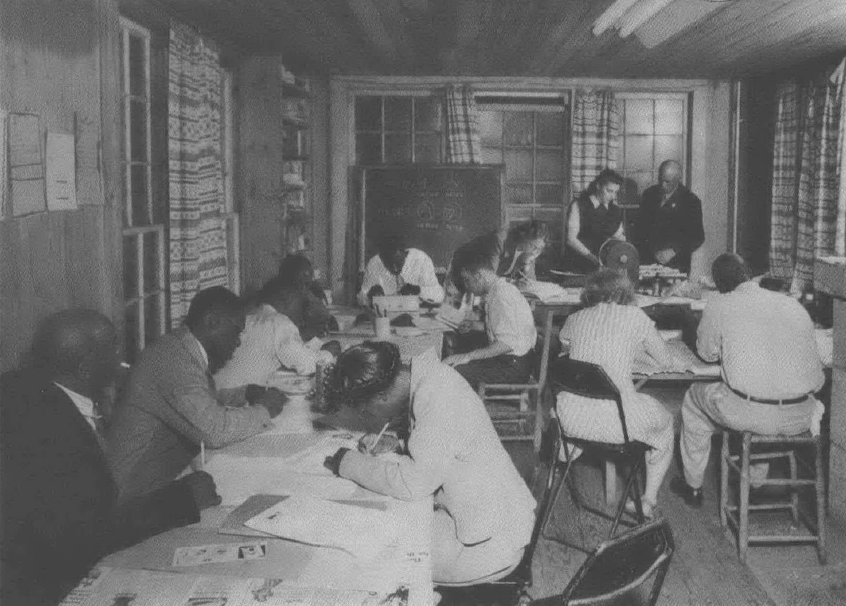

In the early 1930s, Myles Horton returned to his native Tennessee to begin an educational center that combined the folk school tradition of Europe with his own experience of community meetings in the South. With Don West, Jim Dombrowski and, subsequently, a host of other skilled organizers/teachers, Horton implemented a style of informal education that fostered growth and collective learning for generations of trade unionists, civil-rights activists and, more recently, Appalachians struggling to control the world pressing in upon them.

In 1972, the Highlander Folk School celebrated its fortieth year of service—and survival through bombings, inquisitions, forced closures and financial threats. For a new account of the center's remarkable history, see Frank Adams' Unearthing Seeds of Fire: The Idea of Highlander (John Blair Publisher, 1975).

In the following interview, Myles Horton, now retired as Highlander's director, describes the principles of labor education which let people gathered at the residential school learn from each other and connect new concepts to their own experience and to larger social issues. The selections here were excerpted from an interview conducted by Mary Frederickson, a graduate student in labor and women's history, for the Southern Oral History Program of the Univ. of North Carolina.

The only way that you can learn anything is to tie it onto something that you previously know. That's what learning is. That's what labor education has to be.

At Highlander, we took people who were already doing something in their own community, in their unions. They were emerging leaders, people who were just beginning to do something and have a leadership role. If we had our druthers, we would never have had anybody except shop stewards and the officers of small unions who had the full responsibility for running their unions and worked on the job and didn't get paid. They are the closest people to the rank and file.

When they came to the school they would bring specific problems with them, situations that they wanted to deal with.

We would take those students' problems and have them discuss them. They would talk about their situations and how they dealt with them and exchange ideas. It was peer learning; they would learn from each other. Then we'd learn from history and other things, but it was always related to that specific thing. It wasn't subject oriented like at most schools, it was situation oriented, problem oriented.

Professional teachers and speakers had great difficulty teaching this way, so we never had on our permanent staff anybody who had been a college professor, for example. We thought it was too difficult to get them to understand that workers weren't containers into which they poured their ideas.

We did have college people and writers come occasionally to speak. And some were good and knew how to do it and others didn't. Frank Porter Graham, the president of the University of North Carolina, came to Highlander and he was great. He would just sit down and talk. Then I remember we had Jim Warburg, who is one of the most brilliant people on international affairs and who has written books on international policy. He came down to talk with a group of CIO people. He talked for an hour and it wasn't going across, people didn't ask questions. So he said, "You know, I want to apologize to you people. Myles tried to tell me, he spent a whole two hours trying to help me understand how to do this thing. I wanted to do it so badly, but you will just have to undertand that last night I spoke at Harvard and the night before that I spoke at Yale and I don't have any experience talking to people like you. The reason that I came here is because I think that you are much more important than the other people I speak to. I think that this meeting here tonight is much more important than a dozen Harvards and Yales. So I want so much to talk to you."

He was just begging, you know. This guy had written books, he had been a professor and lectured. He said, "Will you help me talk to you? I think that what I've got to say, you are interested in. Will you help me do it so that you can understand it?"

Well, of course, that just won them all over and they couldn't resist a guy like that. Well, they responded. They sat up until three or four o'clock, they sat there and talked, they really tried to help him. They would say, "Now Jim I'm down there in a chemical plant outside of New Orleans and most of the people can't read or write and what has this foreign policy got to do with them? You tell me what I should tell them."

Then they would say, "Well, they won't understand that." So they kept pushing Jim and Jim was loving it because he was really getting somewhere. By midnight, they were really talking and by two o'clock, they had drawn up a two-page foreign policy statement that they understood, that Jim thought was important, that they could agree on and they could take back to the union. They not only took that back to their local unions, they took it to the national CIO convention and they knew it so well, they understood it so well, that they got it adopted as the platform of the national CIO and Jim about fainted when that happened.

He said, "Hell, Myles, I could have spent a week with all the top CIO officials and never got that thing looked at and yet here I am the author of their platform."

Some people won't do it like Graham and Warburg. Some people say, "Why can't I teach like I teach my captive audiences that come to get their degrees?" Well, you can't use people like that.

Union Support

You have to work with people, not use them. For instance, when we started working in our own community, we had mainly night classes and day classes. We had people studying co-ops for six weeks at night, two or three nights a week. Then we started working on a broader base out in the county. A little later on, the WPA started and NYA and CCC and those government agencies and we started working with them. So we worked with men and women in terms of whatever they were into and we got them from organizations that we worked with. Later on, we started working with the unions on a wider basis.

Labor people as a whole are not prone to understand labor education, but the CIO people in the new unions needed some training for leadership. They had these big locals and they needed people to learn to run them. I remember the president of the Rubber Workers was a Kentucky hillbilly, a man named Dalrymple. His people were all mountain people who went to the cities — Akron and places like that. All the local officials were mountain people. They were just like people down here. Dalrymple knew that he had to get some local people trained and we had a place down here that he could identify with, because we were in this mountain area like he came from. So he couldn't think of a better way to do it and he would send people down to get some training.

Then there were local directors that we knew. We finally started putting these local regional people on our board so they could work closely with Highlander in an official way, and we would say, "You've got to help with the teaching and the recruiting. You've got to help shape up the program because it is for you." So they were involved with Highlander; it was their school, you know. They weren't sending people to somebody else's school. They would keep saying, "Why can't you take more of our people? When can we have a workshop?"

If we wanted automobile workers, furniture or textile workers, rubber workers, hosiery workers, food, tobacco and agricultural workers, all we had to do was to tell the union how many people they could send and they would do the rest. We couldn't get the steel workers. John L. Lewis supported Highlander, he endorsed Highlander, he would do everything for Highlander except send miners. And the head of Steel Workers in the South, Bill Crawford, he believed in education and was finally the chairman of the board, but he couldn't get the Steel Workers Union in the South or the national Steel Workers to support Highlander.

Most of the people who came to Highlander learned a lot about how to run a union. But about 25 percent of the people were on committees who wanted to learn specific things: how to do political action and community action, how to put out a newspaper, start an educational program.

We felt to run the most useful program we could, we had to offer all of this and more. Unlike most schools, we had a full time relationship with people and we had a field staff that was out in the field. There were people like Zilla Hawes out organizing for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and sending people back to Highlander. If we weren't running a workshop at Highlander, we were running one out in the field. Maybe two different places at once.

Education has got to be a year-round job, you've got to relate to people on a year-round basis. You've got to be there when they need you, you've got to do other things than educational things. You've got to be known as somebody to have solidarity with, somebody who can be counted on, who will go out in a rainy night when somebody is in trouble.

And you've got to do it from the very beginning. The start is very important because people very seldom get away from their roots. It's hard to. You start the right way, or you don't end up the right way. You still do what you start with to a great extent. You know, this business of children growing up into older people and being like the ones before, you know, there's something to that.

Integration

We made a statement at the very beginning: "Highlander is open to blacks." The first announcement of Highlander said it. So we had a principle established.

Now, we had no takers. Neither blacks nor whites would come on that basis, but our position was clear. We were open. And then what we would do, we would bring black speakers in; the first year there was Charles Johnson from Fisk. We brought people in to establish the fact that we were serious about having blacks and if we couldn't get them to come as students, we would get them to come as speakers or teachers or something.

Now the fact that we couldn't get them to come bothered us because we wanted to get them there, but it didn't bother us as much as it would have if we hadn't established the principle, because we knew that eventually it would help us in working through it.

Then we started working with blacks. We would go to the Chattanooga Central Labor Union meetings and we affiliated with Chattanooga, that was back before the CIO and there were blacks and whites together in unions there. We helped organize a lime plant down in Sherwood, Tenn., blacks and whites together.

We would never do anything except with blacks and whites together. Even though we couldn't get them to come to Highlander together, when we set up a local union or co-op or got a group together, we would always have blacks as well as whites. Always see to it. So, we were beginning to build a little network of who we were in relation to that problem in the minds of people that we dealt with. That was a strategy. Then we started pushing, trying to get blacks as students. They didn't want to come and they wouldn't come because they were scared. It was a new thing and dangerous and there wasn't any reason for them sticking their necks out. So we finally maneuvered around until we got both blacks and whites there.

Once we got them, we made a big huff and puff about it publicly, and we got the state CIO to make a statement saying that this was an integrated workshop at Highlander and they advocated that all unions follow that pattern. Actually we just took one statement and parleyed that into a statewide mandate on it.

Then we would go on in and insist on it. We would almost say that you couldn't come if you didn't. We didn't go quite that far. We almost did, but we made it almost impossible for them not to bring blacks. Then we started getting one or two blacks and started a strategy of working through the blacks, saying to them, "Now, you go back and next year, the next time that you send students to Highlander, you have a moral obligation to see to it that blacks are included." So from then on, we had it made because we had our people in these locals, when it came to a question of sending students to Highlander, who would get up on the floor and insist on it.

Democracy

We believed that there should be real democracy in the unions and that should apply to women and blacks and young and old. I remember when we had some people from Memphis down there, young people, and they said, "Well, you know, the leadership is entrenched in our union. They want us to come down because they want us to be better shop stewards and run better committees, but they are never going to move over and let us have the offices."'

I said, "Well why do you want to move them over? They sent you here." "Yeah, but they are pretty conservative and we would like to have more militant unions."

"Figure out how you do it. Figure out where the power is. Who have they got on their side? What is their support? Which workers? Men, women, black, white?"

"Well, white."

I said, "Okay, get a black working with you. Blacks, women. They've got to have some opposition. Add them all up. Don't just play their game. There is another game that you can play — women, black people, people outside their group."

"Oh, they would work us over. Women? You couldn't have women on there. You couldn't have blacks."

"Okay, then leave things like they are because they've got it sewed up, but don't say that you can't do anything. Just say that you don't want to do it."

Well, before they left Highlander, they began to understand and they went back and did it. They went back and put the combination of women and blacks together and took over the union. It took them about six months, it wasn't hard. Well, there you find democratic principles and tactics that we were helping these people with, practically on a democratic basis. They couldn't have won it any other way because the others were taken up. So we always use these kinds of methods.

We Had a Movement

In this kind of situation, education can be a force, but education doesn't have a power base. It has an idea base, but not a power base. If you are going to be in education, you have to know that you are not running the show. We are here to render services. At times we are respected and loved and then we are courted when we can help union leadership. And when they don't need us, labor education can just be sloughed off.

We had a movement at one time in the CIO. We worked together. Highlander couldn't have functioned if there hadn't been the unions and the unions felt that they needed Highlander or they wouldn't have accepted us.

There was a social movement that was not just unions organizing for wages and better working conditions and security. It was people organizing to do things in their community, taking political action, learning about the world, carrying on educational programs to start cooperatives, to do a lot of things. Education was a part of that, it was kind of the spark that kept those things ignited. And the union was the thing that held it together, that would be the cement. Bbt it hardened pretty fast and we got so that we couldn't move.

We had literally hundreds of people running their own local education programs throughout the South, hundreds that we worked with at Highlander. We had a network of things going all over the South that involved thousands of people a day. Thousands of people a day were involved in those programs. So it had an element of a movement.

What happened to it is the sad story of institutions in this country. I guess in any country. You know, bureaucracies set in and they begin to ask experts to do things; they stop doing things at the bottom. The rank and file stopped being active, and the top people loved it because they got all the credit and glory, and the people at the bottom loved it because if somebody will do something for them, they won't have to do it themselves. They thought that it could be done better by having experts. And they finally delegated all the responsibility to the top officials. Just like we delegate things in government, you know, we don't do anything about government except every three or four years and we don't do much then. We don't have much voice unless we take it. Unions in general got top-downish and the rank and file lost its power to do anything and the muscles got flimsy, and people lost interest in everything except just the purest simple trade unionism. We got back to the kinds of things that they had in the AFL before the CIO, with the exception of a few unions which have maintained a little spirit, you know, because of a few people plugging along. Once in a while it gets so bad, like the United Mine Workers, that they have to have a reform movement, and then you get a new life and a new spark and new people and education going.

But if we could have kept control of the unions in the hands of the rank and file and kept people wanting to run their own unions, running their own affairs and insisting on doing it, and keeping an educational base so that they would continue to get new ideas and learn how to do things, then you could have kept the unions strong and fresh.

Tags

Myles Horton

Mary Frederickson

Mary Frederickson is a graduate student in history at the University of North Carolina. She is currently writing a doctoral dissertation on the Southern Summer School. (1977)