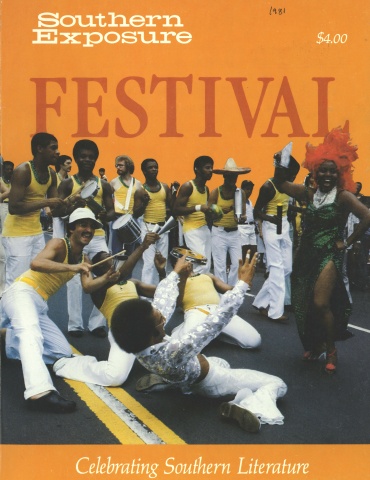

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

As far back as the birth of distinctively American literature — Washington Irving’s short story romances and James Fenimore Cooper’s novels — African slave women were the least identifiable human entities. Black men in contrast received a few “minor” roles: steady the plow, drive the coach and have supportive “yes sar massa”s readily available. But the ebon woman, always portrayed as stoutish, mute and stupid, was never allowed to venture beyond the back burner of the back stove of the back kitchen in the early American writer’s pen and, more pointedly, in his mind.

To say that pre-modern writers were more vulnerable to such neglect is no excuse. Even today, with few exceptions, the black woman is still the least developed character in national and regional literary culture. Nor is “prior” sexism an adequate explanation. Two hundred years after Irving and Cooper, when American art had progressed from European emulation and sputtering definitiveness to internationally acclaimed forms, American heroines such as Henry James’ Isabelle Archer, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne, Theodore Dreiser’s Carrie, Stephen Crane’s Maggie and Edgar Allan Poe’s Lenore were complex women who were influenced by multi-faceted forces and who acted from motivations which were always more compelling than their environs. Thus as individuals, and not stereotypes, they were free to develop beyond societal restraints or traditional literary molds.

As for black male characters, Mark Twain’s Huck has his “Jim Baby,” who, though appearing to be the typically depicted fawning slave, has so much ingenuity that he is able to hustle a white boy “massa” as a cover for escape. In William Faulkner’s works, Lucas Beauchamp and Sam Fathers are black men — even though much is made of their near-white black blood and, in Sam’s case, Indian heritage — who are respected as men, even creating acceptable arenas in which to challenge and usually dominate white men. Later, Richard Wright would conduct an entire symphony of the black man’s rage in Bigger Thomas, Ralph Ellison would set forth one black male character’s naivete and simultaneous intellectual capacity in The Invisible Man, and James Baldwin would command national praise in his many novel and essay definitions of black male selfhood. But the task of creating a black American heroine in depth, of detailing the anguish of her unique dilemma, of delving into the mystery behind her Herculean spiritual strength, has remained for that select group of black American women writers whose creative statements reveal that only in “speaking for ourselves” will the world ever begin to comprehend the infinite source and personal horizon of collective black American feminine experience.

If there are traditional ways of viewing black women in American and, more cogently, Southern literature, they can be arranged in three stereotypical groups: the ever-present Aunt Jemima image; the tragic mulatto fixation; and the sensual animal type. One does not have to look far to find the familiar and simplistic “Mammy” who is also usually shown as prayerful Mother Earth, ever full of mercy, love, sacrifice, seldom angry or vengeful toward her captors and above all never seeking a way of escape. She is Uncle Tom’s wife, Aunt Chloe, in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s cabin — an incredibly stoic woman who waits for him to endure all manner of “cheek-turning” and “back whipping” only to receive his dying spirit years later. She is Butterfly McQueen’s sweet voice calling, “Miz Scarlett, Miz Scarlett” through repetitive reels of movieland. And she is Faulkner’s Dilsey, expected to bring spiritual vision to the self-inflicted judgment of her psychotic white “family.” Filled with prophetic spirit, this pathetic “angel” of simplicity, whom they believed was sent by God to cradle white life in perpetuity, is shown rising above all Compson sins to view “de power and de glory.” “I seed de beginnin, and now I sees de endin,” she says wistfully, still in the enchantment of her vision — the “endin,” however, is not of her own self-effacement but, she hopes, of the Compson’s crucibles. The last we hear of Dilsey, it is again to comment about “them” and not “us”: “They endured.” Unfortunately — when one considers the works of such Southern authors as Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Allen Tate, Robert Penn Warren, et al — the Dilsey-type character is also most of what “endured” in American fiction as a united image of a black woman’s supposed total capacity and potential.

The problem with Aunt Jemimas, fair-skinned tragic pariahs and desirable sex objects, is that they prohibit authentic character development within a novelistic world in which an author professes to attain “truth.” These predictable models are also intended to prescribe all that the black woman is and should even hope to be in white society. The aesthetic standard of beauty in Western culture has always been white skin, blond hair and blue eyes. Thus the black woman was historically only seen fit to rear, scrub and make nations of masters and slaves. She moreover could be available when those masters tired of worshiping their self-made and fragile icons — white women — and reached for more “devilish” features, supposedly intrinsic to black skin, which better satisfied the lust of their hearts. Untouchable aesthetical perfection in the white woman was to be admired, but male physical needs demanded a dispensable body. The black woman, as her younger “Mammy” self, the willing waste receptacle for all excesses, could provide it. And in literature, as in life, she could be shuffled between white men and black men and their offspring; but the art form could never admit that perhaps, in the midst of existing for others, she was really someone else, carving a different image upon her own soul, even sculpting a superior scope for her own daughters.

Perhaps most devastating to the black feminine image in modern literature is the “star” role of this darker quasi-animal female: the sensual being. White Southern authors especially turned the black woman into a modern creation of the medieval misconception that darker-skinned persons were more passionate and that they could be fully understood in solely sexual terms. For instance the 1940s produced the unlikely love affair in Lillian Smith’s Strange Fruit and the absurdity of Roth McCaslin’s mulatto third cousin begging him to return her love and acknowledge their child in William Faulkner’s “Delta Autumn.” Earlier Northern white writers, Carl Van Vechten in Nigger Heaven and Gertrude Stein in Three Lives, had drawn the same sensual characters in mulatto women single-mindedly enthralled with men who not only looked white but who, more importantly, thought white in regards to black people. Mark Twain’s sex-wise Roxy in Pudd’nhead Wilson is yet another early version of a racially confused black woman who thinks only in sexual terms. Roxy, probably correctly, believed that her son, conceived from a secret liaison with her wealthy white owner, could not as a slave achieve the full potential of an aristocrat. So Twain had her switch him with the owner’s other son, whom brought up as her own. In 20 years, Roxy reaps the disaster when, after an easy life gained through various sexual favors with white men in the community, her own son sells her down the river — even after she tells him of his true identity.

The most blatant of these attempts to portray the black woman as sexual beast is Robert Penn Warren’s Amantha Starr in Band of Angels. Like most white writers who try to expand black female roles, Warren presents a black woman whose major goal and motivation is to be white. He draws upon the usual tragic mulatto theme of a child reared to believe that she is the favored offspring of rich plantation owners only to suffer the shock of recognition that she is not only black but also a slave. (Twain used this theme in Pudd’nhead Wilson as did Faulkner and Stowe; the nineteenth-century author William Wells Brown in Clotel: Or the President’s Daughter, 1853, the first novel written by a black American; and Frances E.W. Harper in Iola Leroy: or the Shadows Uplifted, 1892, the first novel written by a black woman in America.)

When, as a young woman who harbored benign disdain for her father’s African slave servants, Amantha discovered that she was one herself, she cried:

Listen - you’ve got to listen ... it’s all a mistake —

it isn’t right - and it can’t be true, it can’t happen

to me, not to me ... I wasn’t a nigger, I wasn’t a

slave, I was Amantha Starr - Little Manty - Little

Miss Sugar and Spice.

Her suspension between white race and black reality continues throughout the story. She is passionately attracted to at least four white men: one as his willing slave mistress; two as sensual temptress who taunts men to wild acts of murder and revenge; and one as a “passing-as-white” subdued, dutiful and utterly miserable wife. The reader is never sure why Amantha passes from one man to another. A craving for sexual relationships which provide a touching identity with whiteness is the only plausible reason. The only black man within her reach, Rau-Ru, is an overseer in her first lover’s plantation; but although she briefly escapes from the Civil War with him near the end of the novel, she never knows him as a human being, a fellow slave or a passionate lover. Ultimately any critical search for a realistic, complex black woman in Southern literature, would lead one to conclude that the answer is not Amantha Starr. Whatever causes lead to the character’s shallow development, it is clear that Warren did not just portray a black woman who wanted to be white; he created a white woman whom he was trying to make black.

The critical issue is a matter of perceived realities: few white writers have ever known who black people were nor what they wanted. To admit human possibilities such as equal intelligence, similar emotions, needs for love, a likewise capacity to hate and harbor revenge — was perhaps too unsettling to themselves or to their readers. Thus societal suppression of black humanness was mirrored even more violently as, through force of pen, Southern white writers continued to create worlds with insufficient atmosphere for black women to express more than stock sensuality or mammyism.

Tragically, the explosive rage of black male writers even forced them to embrace this suppression as a means of dramatically decoding glimmers of black consciousness. Once such men as Wright, Ellison, Baldwin and Baraka had unleashed centuries of rage against the dominant society, emotions were too spent to explore love, or beauty, or the aesthetics of femininity — subjects befitting relationships which unoppressed men would be free to cultivate in their literature. The black male writer had to reflect the realities of black life wherein the man’s first duty was just to keep himself and his woman alive and next to resist their sub-human placement in the world, and occasionally, where safety permitted, to demand from the white world more than just bread, but dignity, hope of graduation from a life of subjugating meniality for their children.

For the black male writer to show just how reprehensible black experience is, for him to force beauty from anger, art from violent imagination, drama from mutual frustration — he fell inevitably into the same trap as his white male counterparts. For instance, Richard Wright reached in the “stock” cabinet for the dependable, religious, unfeminine black grammie and turned her into the stifling, emasculating enemy. Wright’s women are either marshal mother figures who, as preparation for the white world, badger him to imitate their hysterical madness, or else they are mono-minded sexual beings who inhibit his aspirations.

James Baldwin tries harder. But even in his broader world, women are simply appreciated appurtenances to help a young man find his way. And this is also the function of black women in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Unlike the glamorous, wealthy white women who aid the ambitious hero in his move up within the Communist Party, Southern-style mammy figures like Mary Rambo are visible only long enough to feed, clothe and comment on the youth’s “superior” leadership qualities. In this regard Mary is no different from Faulkner’s Dilsey or Warren’s Aunt Sukie; these characters are simply non-persons, sort of mechanical comfort machines, indispensable to the hero’s existence but having no existence of their own. In his essays Baldwin suggests that the racial hell in American consciousness makes it impossible for a black man to function, in life or in art, toward a woman as he would. In fact Baldwin admitted that the task of presenting a total black woman would remain to the black woman author herself.

Other black men writing in the ’60s and beyond still did not find the times acceptable enough to leave the black nation’s oppressive condition as subject matter for their art. So heroes went off to fight wars at city hall, in picket trenches and in corporate worlds, but generally heroines remained in “stock”: unborn, aborted, minimized. When one considers female characters in some of these works — i.e., the hellish char woman in Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada; the sado-sensuous, pseudo-political object in John Wideman’s The Lynchers; and the strong, spiritually supportive women, like Miss Jane Pittman, in Ernest Gaines’ novels and short stories who continue to fulfill the black woman’s expected role as underpinning Southern society — it is apparent that their collective growth has not kept pace with the development of black men whom the writers have made more equal to themselves.

One cannot criticize Baldwin, Ellison, Wright or any other black male writer for first attacking apartheid’s moral corruption in American life. Nonetheless their efforts to grant literary emancipation to the black man leave readers uninformed about stunted black women characters who, left behind, metaphorically stare at the ubiquitous walls of a literary institution which has produced fully known, loved and often complex enough to be loathed white women, but has negated the possibilities of such images among black women in America.

But if the years of the ’60s and beyond opened doors of opportunity for ethnic writers in general, they were no less inviting to black women artists. After 300 years of being “wallpaper,” “mattress cover” and “pot holder” in American literature, the time has come for Dilsey to move over, for her great-great-granddaughters are now speaking, praying, being, not for any Compsons but for themselves. Black American women writers are moving collectively and, though largely unrecognized, have historically moved against the prevalent stereotypes of their literary legacy. They have refused to deploy the Aunt Jemima image; rather they have employed heroines who maneuver constantly to avoid being anyone’s lacky. If any feminine passion is displayed, it is directed toward black men, not white ones. And since Frances Harper’s First book, black women have written novels which more vividly illustrate the anguish of alienated mulatto women who either sacrifice themselves to better conditions for all black people or else portray the schizophrenic idiocy of attempting to conform to the white world by “being” white.

During the pre-depression Harlem Renaissance, several black women novelists emerged in segregated cultural circles who turned the mulatto motif upon its ear. In Passing and Quicksand, Nella Larsen showed that there can be no fulfilled feminine existence as long as a woman’s possibilities are confined to the lightness or darkness of her skin. In one Larsen plot, suicide or murder is inevitable for women who try to arrange their lives with these masks. And while the first three novels of Larsen’s contemporary, Jessie Fauset, may have been designed to authenticate the righteousness of what in the twentieth century had become respected middle-class mulatto lifestyle, Fauset’s last novel, Comedy: American Style, sets forth the tragic unraveling of such fairytale pretenses.

Today the novel of that period which scholars of black American literature most applaud is Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. That book, now back in print, is having a revival through the rediscovery work of novelist/poet Alice Walker and critic Robert Hemenway. Hurston’s heroine Janie Starkes refuses to inhabit the middle-class status of “light enough” mulattoes in the deep South. Janie posits that black women, regardless of their hue, owe their allegiance to black people because there is neither value nor future in attempting to be white. The one passionate love of her life is not an affair of lust but a warm, tender relationship with a black man named Teacake who takes her to the Florida bayous to experience authentic black life. After his death, Janie is contented because she knows the full liberation of being expressive, well-loved and complete — even without man or child in her life. Her artistic ability to command the folk art of this “real” black existence also makes her the second of many multi-faceted women characters to follow in novels by black American women — characters who find maturity and self-expression in some form of artistic creation. Frances Harper’s Iola Leroy was the first.

In 1966 Margaret Walker, in her prize-winning novel on the Civil War, Jubilee, makes a similar statement. Walker draws upon generations of family folklore to produce a woman who, though she is a slave, is able to identify herself as more than just someone’s maid and, when free, is able to establish a more acceptable world for herself, her husband and her children. Vyry, who lives to see the destructiveness that antebellum culture placed upon the “untouchable” white woman, endured and transcended the mold with which the same institution would inhibit her development as a spiritually resourceful and passionate woman. Throughout the work the reader marvels as Vyry makes choices which define and enlarge her own being, regardless of the most grueling circumstances typical of slavery and reconstruction.

Similarly Alice Walker’s Meridian, Gayle Jones’ Corridegora, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, Sarah E. Wright’s This Child’s Gonna Live and Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters, among others, are novelistic structures which allow Southern black women characters room to explore, to grow, to rise above convoluted, preconditioned paths which define who they are and what they should be. Autobiographically, writers like Ann Moody and Maya Angelou, in Coming of Age in Mississippi and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, exhibit what the Southern experience is actually like for black girls and women. They give testimony that the first thing a young black girl must overcome is the culturally imposed psychological longing to look like a white girl. Angelou opens her biography with memories of a young black girl who was typically caught in the schizophrenic horror:

Wouldn’t they be surprised when one day I woke

out of my black ugly dream, and my real hair, which

was long and blond, would take the place of the

kinky mass that Momma wouldn’t let me straighten?

My light-blue eyes were going to hypnotize them,

after all the things they said about my daddy must of

been a Chinaman (I thought they meant made out of

china, like a cup) because my eyes were so small and

squinty. Then they would understand why I had

never picked up a Southern accent, or spoke the

common slang, and why I had to be forced to eat

pigs’ tails and snouts. Because I was really white and

because a cruel fairy stepmother, who was understandably

jealous of my beauty, had turned me into

a too-big Negro girl, with nappy black hair, broad feet

and a space between her teeth that would hold a

number-two pencil.

And Moody explains that modern Southern black women, even in maturity, still cannot accept the same tenets of feminine definition, roles and fulfillments as white women. For black women characters and writers, the task is still primarily to free a race:

I sat there listening to “We Shall Overcome,” looking

out of the window at the passing Mississippi landscape.

Images of all that had happened kept crossing

my mind: the Taplin burning, the Birmingham church

bombing, Medgar Evers’ murder, the blood gushing

out of McKinley’s head, and all the other murders.

I saw the face of Mrs. Chinn as she said, “We ain’t

big enough to do it ourselves,” C.O. ’s face when he

gave me that pitiful wave from the chain gang. I

could feel the tears welling up in my eyes. ... “We

shall overcome some day.” I wonder. I really wonder.

With this same anguish and intuitive yearning for a higher calling than mammyism, skinism or sexism, Alice Walker’s heroine Meridian sacrifices herself entirely — her health, her “looks,” her lover, her children, any “normal” future of home, hearth and husband — to free black people in the South as a civil-rights volunteer. Her self-effacement is necessary for black liberation and has nothing to do with conforming to stereotypes traditionally drawn by an alien culture. Gayle Jones’ Ursula in the hidden ghetto of Lexington, Kentucky, also discovers her sexuality, not as an artificial character who knows nothing of a black woman’s struggle but as a formerly frigid wife who overcomes sexual inhibitions of her own volition. That the mulatto woman must also obtain sexual wholeness, regardless of the legacy of miscegenous white fathers who look upon black women as objects of sexual exploitation and who leave frigidity as one of the many psychic scars upon their daughters, is Jones’ bittersweet secret in Corridegora.

Today black American writers are even redeeming those images of slave women which have been allowed to remain despicable emblems of shame on the blotter of racial consciousness. One example is Sherley Anne Williams’ forthcoming novel, Meditations on History (a segment of which is collected in Doubleday’s Midnight Birds, edited by Mary Helen Washington). Odessa, one of the captured leaders of a slave rebellion in early nineteenth century Alabama, is allowed a stay of execution because she is pregnant. Williams uses exquisite imagination to portray what the black woman’s slave experience must have been like: a condescending white journalist who has just finished a volume, The Complete Guide for Competent Masters in Dealing with Slaves and Other Dependents, is trying to pick Odessa’s mind so that he can write another volume on how slaveowners can prevent insurrection. He learns that the massas must not only fear strong young bucks but also small “docile” women like the fierce Odessa; that she, aware of his sado-sexual attraction to her, has been psychologically manipulating him instead of the other way around; and that she has cleverly used his “childish,” erudite interviews, which assumed her ignorance, subservience and powerlessness, as a ruse to plan her escape. But his discovery comes too late. Odessa is rescued by the same community of escaped slaves which she risked her life to free. One empathizes with Odessa’s kinetic love for the sensuous Kaine, whom the massa kills, her insistence to have Kaine’s child despite the anti-life odds of slavery, and her will to triumph over the literal hell of plantation existence. Instinctively the reader knows that Williams has created a more authentic slave heroine of whom black readers can be proud and from whom white readers can gain insight.

Yes, the issue is perceived reality. Other segments of literary society attempt to perceive what the black feminine experience is like while black women authors write from knowledge and informed imagination. These writers speak for the modern, liberated black woman who refuses to fashion herself after shallow patterns or to offer misrepresentative art. Dilsey may have seen the beginning, but the new black women writers see the end — the end to all Dilseys and their passing white world — because the black woman has always known that women like Dilsey, Amantha and Roxy never really existed at all.

Tags

Sondra O’Neale

Dr. Sondra O’Neale is an assistant professor of English at Emory University and recently directed the Conference of Black South Literature and Art. This article is part of her forthcoming book on patterns of black feminine development in novels by black American women writers. Her review of Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters is found in the book review section of this issue. (1981)