This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

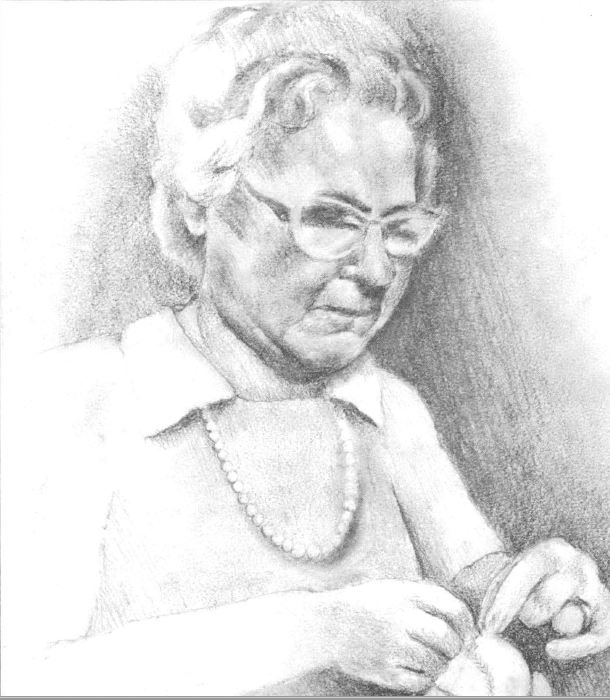

Baseball buffs don’t keep up with such statistical matters as balls per hour or stitches per minute, but Mrs. Stella McEwin does. To earn $2.30 an hour, she must sew the horsehide covers on at least six baseballs or seven softballs. The more she sews, the more she’s paid.

She’s been sewing up baseballs for the Worth Manufacturing Company of Tullahoma, Tennessee, for 32 years. They are now the nation’s largest producer of baseballs, softballs, bats, base bags and leather for other sporting goods. The company started out years ago making horse collars. A machine to stitch the balls has eluded the firm’s inventiveness.

So every ball is hand-sewn, and Mrs. McEwin is one of their premier sewers, doing many of the company’s special orders. When she’s finished with a ball, the hide is taut, the stitches even and the seam all but invisible beneath the cross-hatched pattern. She frets when a ball doesn’t look or feel just right.

Most of the company’s balls are sewn on a piece-work basis in private homes around Tullahoma. The sewers pick up canvas bags containing 10 dozen balls at the factory, then return the finished product later. Mrs. McEwin, however, sews in the factory.

“I was raised on a farm outside Lynchburg,” she said recently. “My aunt was living up here and I came up looking for a job. I was raised on a farm. My aunt called Mr. Parrish — Chuck Parrish. He hired me and sent me to learn how to sew with Mrs. Mollie Lynch. She was getting up in years.”

The thread-wound balls and white covers arrive at Mrs. McEwin’s bench in bags or piles. She dampens the backs of two pre-cut hides with water, then snaps and pulls the leather between her hands to soften it. She lets the hides sit a minute while she sets the ball in a clamp between her legs and cuts and waxes the thread. Two needles are used in the process.

Next she quickly daubs rubber cement on the backs of the hides and carefully places them on the clamped sphere. Staples hold the hides in place as she stitches, first running each thread through the ball’s windings, then into pre-punched holes in the hide.

Each hide has 92 holes, and the needles are cross- or double-stitched until all 184 holes are pulled together. Then the needles are carefully threaded back through the ball’s windings at the seams and tied off.

“I never was a fast sewer,” Mrs. McEwin declared, having finished the ball in less than three minutes.

“Back when I started, you only sewed four an hour. I can’t remember how much we were paid. I think it was 30 cents. But the NRA, or some government law, came in after I started working and that raised our wages.

“When the government would raise the minimum wages, they would increase the number of balls we had to sew up to where we are now. They gave us tests, you know. They used the tests to average out how many balls we had to sew.

“The most I ever sewed was 66 softballs in eight hours. That was some years ago.”

She starts work every morning at 6:30 a.m. The shift ends at 3 p.m. “Then I go home and start another shift,” she said with a soft laugh. Only one of her five children is at home now, but her husband is totally disabled with a back injury.

“I like to sew balls. I’d rather do this than anything else in the plant. I’ve heard ladies say they would sit down and crochet to relax their nerves. That’s the way I am sewing balls. I relax my nerves. But I just never could make much money at it.

“I work with em until I get each one the best I can. It gets pretty tiresome, especially when you stay with it a steady eight hours.”

Back in 1945 when she got the job, there were about 500 persons around Tullahoma stitching balls in their homes. Today the number is fewer than 100. The firm now has plants in Haiti, Nicaragua and Jamaica.

In those days, every ball had a leather cover. Today many are plastic. “The leather and everything is different today,” she explained. Back when baseball first became popular, horses were a central part of American life, city and country. Tanneries still use horse “butts” to make cordovan shoes, but most of the hides come from overseas. Not as many horses end up in the tannery upon death nowadays.

Does she ever wonder if a ball which leaves the plant to become a part of baseball lore is one she has stitched? “No, not really. I’ve never gotten interested. I’m not much of a ball fan. I should be, I guess, but I’m not. I don’t have the time, what with working and a family.”

Tags

Frank Adams

Frank Adams is author of Unearthing Seeds of Fire: The Idea of Highlander, a teacher and long-time friend of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is writing a biography of Jim Dombrowski. (1982)

Frank Adams interviewed Mrs. McEwin while traveling through the South for the Institute for Southern Studies’ syndicated column, Facing South. (1979)