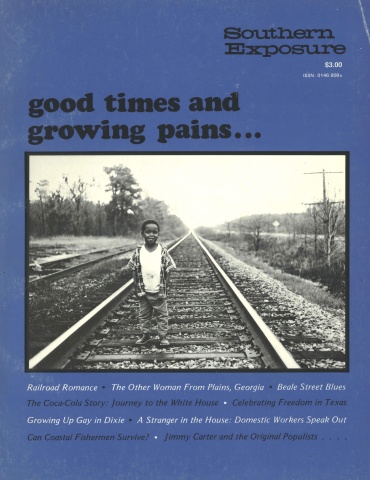

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 1 "Good Times and Growing Pains." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The black houseworkers’ narratives which follow are part of a book-inprogress, A Stranger in the House, which looks at how black women from the South have fared as domestic workers in the North. In the homes of the well-to-do, black women have lived, cooked, taken care of children, and become an important part of a family’s daily life. Employers of household workers are frequently the very people who can best afford to create homogeneous social environments which isolate them from racial, cultural and economic outsiders; yet they open their homes to women whose lives differ from their own in essential ways. This contact has often been debasing to black women; it has rarely been lucrative. Encounters with the white middle- and upper-class world have made these women expert participant-observers in the complex area of racial interaction. To live as a stranger in a strange and sometimes unfriendly environment is not easy, but the women interviewed have adjusted without submitting to despair.

The major historical event in any account of household workers is the great wave of immigration which has carried black women from the rural South to urban centers in the North for close to 100 years. When Reconstruction ended in 1877 and Jim Crow laws were passed throughout the South, the paternalistic mood of race relations was replaced by increasing violence and terror. To young blacks experiencing cruelty, poverty and the treadmill of agricultural labor, the North appeared to be something different. It promised greater racial tolerance, expanding industry with peripheral jobs for unskilled black workers, and a growing middle class which sought unskilled poor for domestic service.

In The Negro Peasant Turns Cityward, Louise Venable Kennedy1 describes this “push and pull” syndrome: Blacks felt themselves pushed out of the South by a sharecropping system which put little or no capital in the hands of black workers. They felt pulled North by more diversified employment opportunities and the possibility of better wages. As a result, disenchanted young blacks began heading North in the 1880s by the hundreds.

They were pioneers of sorts, ambitious people who were willing to leave a familiar world because they hungered for a better life. White Southerners looked upon this exodus with scorn. Many viewed the new generation as “restless, dissatisfied, and worthless” and they recalled somewhat wistfully “the faithful, courteous slave of other days, with his dignified . . . humility.”2 Of course, this was somewhat short of disinterested social observation. The Southern agrarian economy rested on the backs of poorly paid farm workers who were now departing in droves.

From 1880 to 1900, the black population of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Illinois nearly doubled from 235,000 to 411,000. This growth rate continued in the next 20 years, due largely to massive immigration from the South. Between 1910 and 1920, the percentage of blacks in Alabama, Louisiana, Delaware, Tennessee and Mississippi decreased, and the rate of increase in other Southern states was rarely higher than 15 percent. In contrast, the black population rose in New York by 47.9 percent and in Michigan by 251 percent. In that decade alone, the number of Southern-born blacks in the North jumped from 415,000 to 737,000.3 The economic and social significance of this movement was massive. Only in the last few years has the number of blacks leaving the South dipped below the number entering the region.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, black women came North in greater numbers than men — five women for every four men — and 59 percent found jobs. Often they were exploited by employment agents who traveled the South offering blacks transportation and a guaranteed job on their arrival in Northern cities. Naive young women became, in effect, indentured servants by accepting terms of service that gave them “Justice’s Tickets” to the North. They filed aboard steamships that took them up the Atlantic Coast, and were segregated uncomfortably in steerage quarters along with luggage and white travelers’ pets.

The vast majority of these women found employment as private household workers. By 1910, New York had one of the highest percentages of working black women in the nation (only five states in the agricultural South had a higher percentage); and four out of five of the women were involved in domestic service. The message was clear — if you want to work, and if you’re sick of rural life and the servitude of tenant farming, come to New York and become a domestic worker. Many women were happy to make the move, but to suddenly pass from a sharecropper’s cabin in the rural South to the homes of the white middle class in Northern cities was an enormous adjustment, to say the least.

There is no question that these black women were the most marginal group in America’s labor force. During World War I, America’s manufacturing and mechanical industries began employing black women to help meet Europe’s new demands for war materials. With this temporary opening for black women, the percentage employed as domestic workers in the North declined from 80 to 75 percent by 1920. But the pithy observation, “Last hired, first fired” surely applies to the history of black working women.

Not until after World War II did women begin to penetrate the industrial labor market and professional areas in significant numbers. To be sure, the percentage employed as domestic workers has declined steadily over the years, but the greatest changes did not come about until fairly recently. In 1965, there were still close to one million black household workers, about one third of all black working women. From 1965 to 1974, a dramatic change took place that saw close to a half million black women leave their jobs as household workers. The civil-rights movement, the War on Poverty and the expanding service-oriented economy combined to move black women into clerical and professional jobs for the first time. Young women who grew up during the years of civil-rights protest are usually loath to enter domestic service. And fair hiring practices and job training progams in the mid-1960s have made it possible for many to find work outside of white households.

Neither of the women interviewed here found it easy to make the transition from South to North. The rural South was the setting for childhood experience — a place of poverty and racial injustice, but also the scene of close family ties and cherished memories. These women turned North for much the same reason as their predecessors of almost a century ago. The Greyhound bus has replaced the Dominion steamships, but Rose Marie Hairston’s narrative reminds us that even recently there have been ruthless employment agents peddling dreams of travel, recruiting young women with promises that fall short of reality. Some of these women were lucky and found work with families that offered them material comfort and sincere friendship. For others domestic work has been a lonely, difficult experience. Fortunately, the women brought with them a warmth characteristic of their Southern roots, a keen sense of human behavior, and a stubborn belief in their right to be treated decently.

FOOTNOTES

1. Louise Venable Kennedy, The Negro Peasant Turns Cityward: Effects of Recent Migration to Northern Centers (New York, 1930), p. 44.

2. These remarks were made by Southern farmers who testified before the Industrial Commission in 1899-1901. They are cited in Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto (New York, 1971), pp. 25-26.

3. All statistical information in this essay comes from materials assembled by the Bureau of the Census. Negro Population in the United States, 1790-1915 and Negroes in the United States, 1920-1932 are both invaluable.

Roena Bethune

At one point in the following interview, Roena Bethune remarks, “They [the employers] don’t care anything about you. They don’t want to know nothing about your background; they don’t even want to know what’s going on in your home. All they want to know is what you are doingfor them.” Again and again, the women I talked with have told me that they shared more of themselves in our two-hour interview than in two years with a single employer.

As houseworkers they are rarely permitted to fully exist: it is not necessary that their full reality as human beings be taken into account in order for them to perform their tasks. As a result, these women spend much of their lives cut offfrom their own people and surrounded by people who rarely allow them to assert themselves as integral beings.

Never Discussed Hard Times

I was born the 14th of December, 1936, in a little small town called Fayetteville, North Carolina. Coming up as a child, I can remember us living in about a seven-room, white house on Merkson Road. My mother, she was a domestic worker. She worked in people’s homes taking care of children and housekeeping. She could only do so much for us because she had to take care of all the bills and everything because our father had separated from us. My mother, she never received welfare checks. She always believed in going out and working and trying to take care of us herself. And I remembered the time that she would often tell us, “I don’t know how I am going to make it, children, but by the help of the Lord we will make it.”

She would earn something like $10 to $12 weekly, and we had to live off of this. She had very bad days and she had some good days. As for raising us, a daughter and a son, she would have to go out to work and leave us — and as me being the oldest child at home, I had a lot of work to do in the house. My mother would always tell me that I had to clean, and I had to cook if necessary. I was only about the age of nine years old when I started to learn about housekeeping. My mother had nobody to help her take care of us, but only herself.

Ever since I can remember, my mother worked for white families, but she never discussed with me about the hard times or nothing going on with the jobs. I was only a little girl; I can’t remember so much about those times. The only thing that I know — she used to come in the house, and she’d be telling us, “Oh, my day was so hard. I had so much work to do, and I have to come home, and I have to do lots of things. You children have to help me out.” That’s about as much as I knew. I think my mother really didn’t want us to know how hard times was. But, you know, by looking on and observing you could see the expression on her face, you could tell when times come that wasn’t so good.

I never went on the job with my mother. She used to work for this family — they had children growing up like me and my brother — and they would give my mother shoes and clothing for me and such things as that. When I was quite small, I didn’t know no difference, but as I became to be a teenager I didn’t like it because I wanted new clothes. My mother would bring things home, and I knew that she’d gotten them from someplace that she was working. I didn’t want to wear them, cause in school the kids would laugh at you and say, “Ugh, your mother let you wear hand-me-down clothes.”

I remember my grandmother, when I was growing up like the age of 12 and 13, she wanted me to wear those long dresses, and I don’t want to wear those long dresses. I used to have to wear those stockings, like with the seams up the back of the legs. And I would go to school and pull the stockings off in the bathroom, and just before time to come home I would put them on. I knew I would get a whipping if I didn’t return home with things that I wore to school.

We was the type that had to go to church on Sunday, and through the week we went to school every day. And when we come back home we had an obligation in the house to do, so we did not have the time to be running around out there in the street to find out what was really going on out there. Our time was occupied in the home. We lived in a separate world. After I was 15, things was better. And at 16, going on close to the age of 17, I was married. So that’s about as much as I can say about coming up.

Started Moving Fast

I met my husband in Fayetteville. We had an army base there which is called Fort Bragg. A lot of GIs was there, and my husband was a serviceman. We met each other downtown and we started talking. I was walking down the street and he was standing with some GIs at the corner. Myself and a couple of girlfriends was walking, and so the guys started talking, and so we just made a conversation, and he asked me if he could make a date with me. I hesitated, and we gossiped for a while. So I told him he could come back at Saturday afternoon. My mother didn’t really approve of it. I started thinking about growing up and how you don’t get things that you want, and I said, “Well I met this boy, a GI, and I know he have money, and he can maybe give you money sometimes and help out with, you know, if it might be something I wanted, he would get it for me.” So we dated for about four months, and then we got married.

For five years we was very happy together, but then my husband — I really hate to say this — we started having trouble in the home. He started going outside, and he found something outside better than what he had in his home — or he thought he did. After that we separated and I came up to New York.

Believe me, I was here one week and I was ready to go back. I had heard a lot about the big city, and I had heard a lot about the bright lights. And when I came and I saw all the tall buildings and saw all the people moving in the streets, I said, “Who in the world could live in a place like this with the people in the street; they’s pushing each other, it’s overcrowded, and everybody’s in a hurry, nobody have time to even speak to each other. How in the world can people live in a place like this?” And I was ready to go back home.

I was living with my brother and his wife. They had been living here already, about five years before I came to New York. So, my sister-in-law, she used to tell me, “Roena, you realize you never been in the city before, and the city is much different from just where you come from. You come from the South and you never seen a lot of people all in one place together like this. But if you stay here a while, you will like it. And you will make some money, and you get your own little bank account started, and you find out that you don’t have to be in a distress for money. You’ll have money to spend, and you’ll have money to save, and you will like it then. The reason why people don’t speak to you when you walking — they don’t have time for talking with you the way people did at your home. Their work hours is different; some people be going to work at different times, and nobody don’t have time on the street to be speaking and stopping and holding conversation with each other. There is a lot of difference in this place than in the place where you just come from.”

I couldn’t understand that, so after two years, I told my sister-in-law, “I’m going back home.” I went back home and found I pretty much had gotten used to it here. It was just like a storm had passed over, and I could not get adjusted to living back there any more. So I told my mother, I said, “I am going back to New York.”

She said, “Well, you must be going to take the children.”

I said, “Yeah, when I go this time I’m taking my family because I won’t be coming back to the South to live anymore.”

When my kids came here, they got adjusted right away. They didn’t even have to go through no struggles or hard times. They started school the third day they was in New York. They caught on to everything much faster than I did. The way that the people lived here was altogether different from the way I was raised. Even in their houses, people were rushing around and I could not understand it. Like when they would get ready to cook a meal, they just get the food together and they put it on the stove, and they have this ready in five minutes, and they have that in five minutes — it was just a whole new life for me.

It was like everything was moving so fast. And I was never used to anything like that growing up in North Carolina. Then after I got adjusted to everything I came to know how everything was moving in the city, and I started moving fast like everything else.

My first job in New York, I was a chambermaid doing household work at the Saint George Hotel in Brooklyn. As long as I worked in the hotel, the management was great. Dealing with the guests, that’s where the little run-ins would come in. I would go in to make up the bed. As a routine, the customer occupying the room is supposed to be out of the room to let the maid make the room up. A couple of times when I’d go to the room the door would be unlocked — I’d go in the room and the man would be in the bathroom closed up, and he would say, “Come in, don’t you like to make some fast money?” He’d be nude. I got very angry, very angry, and I would run out of the room and go to the nearest telephone that was on the floor. I would call the desk and say, “The man in such-andsuch a room, he’s in the nude in the hotel, he’s giving me a hard time, and I refuse to make this room up because he’s not supposed to be in the room. He’s offering me money, and I don’t like to be going through stages like this because it’s very terrible and embarrassing.”

So the manager would say, “Well, just stand outside in the hallway, somebody’ll be up in a few minutes and we’ll get him out.” So they’d come up and they’d talk to the guy and they’d get him to leave the room. Then I’d go in and make it up. Several times this happened.

There is a lot of things you go through working in a hotel. It was a very terrible embarrassment — some of the things, you wouldn’t even want to approach nobody telling them about it. You try to get out of the room as fast as you can; you go down and make complaints. What can you do? These things happen living in a hotel.

I think it made a difference I was black — the way they would approach you, you know. You could read them, what they think, “Well, how much money can you be making for a job like this? I know that you will like to make extra money. You can’t be making but so much, and nobody would never know about this but me and you. I can get over fast with you.”

Now the way I feel about white people, I don’t hate them or nothing, but I do have a little discrimination against them because, you know, it seems like they only class all the black people as one way. As far as I’m concerned with the white man or the white woman, when I go out there and I do a day’s work for them, I just do my work. As far as I am concerned they don’t love me and I cannot love them because I know that there is a space difference in between; there is a racial gap, because that white woman or white man that you go and work for in their house, when the time comes for them to serve dinner, they will not let you sit down at that dinner table and eat with them. They will tell you, “Serve us Roena, and then after you serve us you can have your dinner in the kitchen” where you do the cooking, not in the dining room where they sit down and eat their dinner themselves. So you know when things like this happen, there is a complex racial gap somewhere.

Rose Marie Hairston

Rose Marie Hairston’s apartment was on 102nd Street, just a block west of Central Park. The shells of three abandoned cars gave the kids on the street a prop for their various games. None of the locks worked at the entrance of Rose’s fourth floor walk-up, and all of the mailboxes had been pried open. The entrance smelled of urine and garbage and decay — a depressing place. Before our interview began, she explained to me that there had been three fires in her building in the past month. The way she saw it, her landlord preferred to collect on fire insurance rather than throw away money on legally required maintenance and repairs. She would have to find a new place soon because the city was about to condemn the building. She laughed as she told me this, and her laughter puzzled me. Her efforts to get her landlord to provide her with a safe and decently maintained apartment seemed frustrating, infuriating and exhausting, but not at all funny.

Later, as Rose began to recount her personal history, Donna Jaykita, her 11-year-old daughter, came to the kitchen door and listened. She clearly enjoyed her mother’s stories, and Rose Marie seemed more comfortable delivering her narrative to a familiar face. For the most part, the daughter was perfectly quiet, but a few times she broke into laughter that illuminated the sources of her mother’s own laughter. She only laughed at stories in which her mother suffered or was momentarily helpless. Rose Marie’s stories informed her daughter of what she might expect as a black woman in America, and through her laughter Donna Jaykita acknowledged that her mother’s message had been received and understood. For both, laughter was a means of defiance; it stood as an assertion of freedom against adverse circumstances. No crisis could finally bring them down or break their spirit.

We Were Very Poor

I was born in Martinsville, Virginia, 38 years ago. There’s mostly furniture factories, farming, tobacco there. My family had their own house, but we didn’t live there all the time. My parents moved to West Virginia, and my father was a coal miner. He was a motorman in the coal mine and a brakeman. A motorman drives down in the mine to bring the coal out. Sometimes he was a brakeman, and he would ride on the back of the little car, which was very dangerous. I forget what it’s called, but from working in the mine he got fluid in his knees and elbows and up in his shoulder. And from getting his back hurt and his hip hurt six or seven times, it caused him to have a type of arthritis. My father started working at the coal mine at age 14, and he was retired about the time he got 40. He had been hurt a lot of times, you know; he was all broken up.

I was a good-sized girl when he retired. We wasn’t afraid because we used to go in the coal mine also. We couldn’t afford to buy coal, so we used to have to go in some of the strip mines and get the coal. Well, you know some people could afford it, but we were very poor; we couldn’t afford to buy the coal or the wood or anything like that. Sometimes we couldn’t get in the mines cause they had a watchman, so we would have to go over on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad and wait for the train car to come by.

The cars used to be loaded with coal, so my brother and I would jump the train and get on the car and throw off enough coal. Sometimes we would throw off the coal and ride the train a long ways, and then when we got back, somebody else had picked it up. So we would have to wait for another train to come by.

In West Virginia we never knew anything about racial prejudice. Really, we never heard anything about that until we went back to the state of Virginia. Where we lived around the coal mine there was Jews, Italians, Hungarians, Poles and just about any race you could name. Everybody mingled together. When I was about 10, my brother Maurice and me went back to Virginia on the farm for a summer. We didn’t know what they were talking about when they used to say “colored people.” In West Virginia we didn’t use the words. Everybody there was together. But when we were going to Virginia, we got off the bus to go to the bathroom, and we wanted something to eat, and we saw a sign said “Colored in the Rear.” We went in there — it was a little, dirty, greasy room about the size of a good chicken house. It was so dirty in there. And then we wondered why all the white people were sitting up in the best part of the bus. Even the bathrooms said “No Colored.” Even the telephones had big signs that said “No Colored.”

My grandfather who lived in Virginia was working for Judge Whittle, so we stayed there and worked for him awhile. We ran into trouble one day. We went to the Judge’s brother’s house to do some work. His brother had this little eight-yearold girl, and her name was Ruth. So we went around to speak to Ruth, and we said, “Hi Ruth, pleased to meet you.” And my oldest brother, Raymond, who lived there with my grandfather all the time said, “You have to call her Miss Ruth.”

I said, “We got to call her Miss Ruth?”

He said, “Yeah.”

I said, “Well, I ain’t gonna call her Miss Ruth.”

And Maurice said, “Well I ain’t gonna call her no Miss Ruth; that’s a little girl. Momma told us don’t call nobody no Mr. or Mrs. down here.”

Raymond said, “You have to call her Miss Ruth, cause if you don’t they’ll take you off and beat you.”

I said, “Well I don’t think they can beat us,” cause we thought we could beat anybody. My brother got a kerosene lamp one night, and we slipped into the dog house where my grandmother and grandfather couldn’t see us, and we wrote a letter to my mother. We told her that we had to say “yes sir” and “no sir” to children, and that the people down there called you “niggers,” and when they wanted you to do something they called you “boy” or “girl” or “nigger.” And we didn’t like it. My brother didn’t understand it, and he was always fighting with the kids.

The schools was all black. We would get up at four o’clock and have breakfast and do some chores like milk the cows and feed the dogs and different little things like that. Then we would walk seven miles to catch a bus, and the bus would take us into town, and then after we got into town we would have about another mile to walk to school. Sometimes in the evening if it was nice, we wouldn’t even catch a bus — we’d just keep walking and walking and walk all the way home. We got out of school about three o’clock and sometimes it’d be about five or six, sometimes seven o’clock, before we’d get home because we’d stop and fool around, and throw rocks at the white children. You know, we’d be walking in the country and sometimes they would say, “Niggers, you gonna spoil the walkway here.” And my brother would hit them with a rock or something. We’d throw rocks and hit them in the head. We would fight them. And then we would run and run. Sometimes they would chase us, and there would be a lot of them, there’d be grownups too. It was fun.

Bought and Sold

When I was a little girl, I always had hopes of being a nurse or a doctor. I always wanted my husband to look like my father. I wanted my husband to be his height, his complexion. My daddy was not a big guy, but he was a handsome guy. I said if I ever married I wanted a big farm and a lot of children. One of my sisters, she wanted to be a doctor. Another one wanted to be a nurse, and one wanted to be a schoolteacher. We’d say that one day we’d be the Hairston clinic. We always wanted something that would help others. One time we said we’d work and make a lot of money, and then we’d go back to West Virginia and have an orphanage. Unfortunately, it never happened.

I was about sixteen-and-a-half, and I was reading a newspaper. It said, “Ladies and Girls 18 and over: Jobs in New York.” And you didn’t even have to pay to come to New York. And this ad said it paid $125 a week. I said, “Oh boy, that’s good! I think I’ll go up there and talk to this man.” He was a preacher, too, and that’s what made me mad. It was just another old gimmick. Anyway, I went up there and he interviewed me. He said, “How old are you?” I told him I was 18, and he kept looking at me.

He said, “I don’t know, Rose, you look very young. Matter of fact, you look like you’re no more than 12.”

I said, “No, eighteen.” So he told me to bring him proof that I was 18, or bring my mother. I told him all right. I caught the bus and went back home and got my cousin to come back with me. She was a much older lady than I was. She told them that she was my mother. She gave her consent for me to come to New York. So he said all right. He told me to come the next day and that he would meet me at the bus station. Then he described the persons that were to meet me in New York on 50th Street. So I met him the next day, and he gave me the bus ticket and he said, “Good luck, Rose.” I said, “Yeah.”

And he said, “When you make all that money, put it in the bank.” I wasn’t scared, I was determined because I thought $125 a week was along ways from getting $7.50 a week.

I didn’t tell my mother I was going. She kept asking, “Where you going?”

I said, “I’m going over to visit somebody for a little while.” S

he said, “I think the right thing for you to do is ask me to give you permission to go. You don’t just get ready and go.”

I said, “I want to go visit a friend over in Lewisburg.”

“Well, all right. But you don’t need a suitcase just to take two or three dresses, do you?”

I said, “No.”

She give me this brown shopping bag to put the three dresses in and some underpants and bras. She asked me, “You want me to go to the station with you.”

I said, “No, I’m a big girl; I can catch a bus.”

She said, “When you get there, you call back.” There wasn’t but one telephone in the neighborhood, so everybody knew your business. She told me to call back Miss Wilson and tell Miss Wilson that I had got there all right.

I went over to the bus station and met the preacher, Brother Plow. He was there with my bus ticket. I jumped on the bus. I was so excited. I was looking out the window, and I was listening good for the man to say New York. I was so excited. I said to myself, “Oooh, now I get to see the movie stars.” I thought you’d probably see them on the streets. I had read a book about Harlem, and I was dying to see Harlem — 125th Street, the Apollo Theater, and I was dying to see 42nd Street. I didn’t understand what Wall Street was, you know. I thought it was somewhere all the rich people and celebrities be — that they’d be there just for you to look at.

When I got off in New York, I saw the people walking — it looked like everybody was walking fast and the cars was whizzing. I said, “Golly, if I get out there on this street, I’m gonna get hit by one of them cars. It’s too crowded in New York.” Then I saw there was two fellas, two Jewish fellas, there to meet me. I had a photograph of them. They told me that I should come with them, that they were there to meet me. While we were walking down the street, I would look up at the buildings and I ran into a stop-sign. After that I had a stiff neck from looking up at the buildings.

I got in their car and went out to the agency in Long Island. Leaving the city, I got disappointed. I said, “Oh my god, I just left the country and thought I was coming to the big city, and the man was trying to send me back to the country.” The man in the agency would tell the people, “I have this nice girl here, she’s very attractive, she’s 18, and she’s good with children.” You know, they didn’t know a thing about you. So they would say, “We’ll bring her over in an hour, and when we get there, you have to give us $150.” I said to myself, “He’s selling the girls. I come all this way just to be bought and sold.”

They took me out to this lady. I remember her well — Mrs. Burke at 250 Central Avenue in Cedarhurst. I got there and looked at this big old apartment building and I said, “It sure is a big old place.” I had the idea that she lived there in that big old building all alone, and and she expected me to clean it all by myself. I got in there in this little apartment, and she showed me through the rooms. I asked her, “Where do your children live?”

She said, “Here with me.”

“Where would I live?”

“Here with me.”

“Well, where?”

“You will live and sleep in this room with my children.”

“I have to share this room with your children?”

I didn’t like it because the little girl slept in a cradle and I slept in one bed and the little boy slept in one bed with me. I never liked to sleep with anybody. Then I had to get used to when the lady would get up early and leave, and you didn’t see them no more til five or six or seven o’clock. Then she would come in and have something to eat. She didn’t spend time with the children. I would think she don’t love her children; she don’t stay home. I wondered why.

Somebody I Work For

I worked there about a month, and I kept asking her, “When is payday, when you going to pay me?” She said, “Oh, you’ll get paid. Do you want me to give you money until you get paid?” So I said, “Yeah.” So she gave me money. Her husband took me to Robert Hall’s, and I think I bought a coat and two dresses and shoes. Anyway, I ran out of money, and he came over to the counter, and he asked me did I get everything I wanted, did I have enough money, and did I want anything else. I said no. The lady behind the counter said, “Gee, you have a good boss.”

I said, “Boss?”

And she said, “Do you work for him? Is that your husband?”

“No, I work for him.”

“Well, that’s your boss.”

I said, “Well, I just say it’s somebody I work for.”

When it came time to get paid, they didn’t owe me, I owed them. It came up a big argument. I told her I was supposed to get $125 a week. She said, “No, I’ll show you on the contract.” So she went and got this contract, and she showed it to me. We was only supposed to get $100 a month.

I told her to get in touch with this agency. I told her, “I’m from the country, but I got sense enough not to work for $100 a month. I could stay at home and work for $100 a month.” We called the agency, and the agency had went out of business.

She told me that she couldn’t afford to pay $125 a week. She said, “You don’t do a lot of cooking.” I said, “Yeah, I understand that, but I sits here day and night taking care of your children, taking them to parks. I had to spend my money, cause when I take them to the store they be hollering about what they want. I didn’t want to be embarrassed, so I used my money to buy them things.”

She offered me $40 a week, and I told her I’d try it for awhile till I found something better. After that she began to get very nasty and prejudiced. When her company came, she said she didn’t want me to sit in the other room and watch TV. I would have to go back into my room until her company left. One day she asked me, “You wasn’t used to eating steak and pork chops in West Virginia, were you?”

I told her, “Yes, I was used to good food in West Virginia.”

So she said, “Well, the maids don’t get treated like the family.”

I said, “Well, I don’t know what you mean by ‘maid.’ A maid is somebody who works in a hotel, right?”

“No, all of you that came up here are maids to us.”

So I said, “Oh, you mean that this will be something like slavery time?”

She was from Georgia, and people were still treated like slaves in the Deep South till about 1960. I began to get very angry when she told me her parents had a lot of slaves. Then she said, “I wish it was slavery time, I’d make a good slave out of you.” I got real mad and cursed her. One word followed another word, and then I got so mad that I slapped her. I slapped her hard as I could. I went into the bathroom, and the little boy came into the bathroom and bit me on the leg. I looked at him a long time and then I grabbed him. I started to throw him in the bathtub, but then I thought better of it. So I grabbed him and picked him up, and I turned him upside down by his feet and started to shake him. Then I just go so- mad that I took his head and I put it in the commode.

She asked me was I crazy. I told her no. She said, “Well, you had better go back to West Virginia where they allow you to do that.”

I told her that I was going to get me another job. I got my clothes and I went to a friend’s house. Later, I called Mrs. Burke and asked her to pay me, and she said she would pay me when I stopped by. I felt a little uneasy going back, so I asked this boy, one of my friends to go with me. He went and got his two brothers and and said, “Come on, go with me back to get the rest of Rose’s things.” They were great big guys, six foot four.

So I rang the doorbell, and she said, “Who is it?”

I said it was Rose.

She said, “Well come on in.” I started to open the door, and my boyfriend said, “Let me open it.” So he opened the door, and when he opened the door, he looked behind the door, and Mr. Burke was standing behind it with a car jack. I guess he was going to hit me. And her mother, father and brother was standing there waiting for me.

I got my money and the rest of my things, and she tried to talk me into staying, but I didn’t fall for it. I just laughed a lot. I guess it runs in my family, my mother laughs a lot too. So I got me another job.

Tags

Robert Hamburger

Robert Hamburger is the author of Our Portion of Hell, an oral history of the civil-rights struggle in Fayette County, Tennessee, published by Links Press. The interviews in this article are part of his forthcoming book, A Stranger in the House. Photos are by Susan Gallagher. (1977)