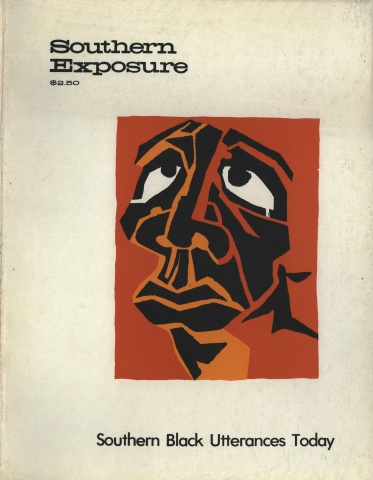

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 3 No. 1, "Southern Black Utterances Today." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Well before the twentieth century, Black people began an exodus from a South politically, socially and culturally dominated by such white terrorist organizations as the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camelia. Utilizing every available avenue of escape—cars, buses, trains, on foot—they came North to settle in the urban areas of America and to confront the nameless future. In "Lenox Avenue Mural," Langston Hughes immortalizes their trek:

. . dark tenth of a nation,

. . .

from Georgia Florida Louisiana

to Harlem Brooklyn the Bronx

but most of all to Harlem

dusky sash across Manhattan

I've seen them come dark

wondering

wide eyed

dreaming

out of Penn Station"

The new migrants brought their life style and culture with them. We know too that their ministers and lawyers, doctors and society people, bright young men and women, followed in hot pursuit. We have come to realize only recently, however, that the migration spurred the exodus of talented writers from the South, most of whom were determined, in the words of Richard Wright, "to fling myself into the unknown, to meet other situations that could, perhaps, elicit from me other responses. . ." Among those who were destined to become strangers in a very strange land were James Weldon Johnson, Zora Hurston, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, John Williams, Hoyt Fuller and Ernest Gaines. In concert with others, sometimes intentionally, sometimes not, these migrants were largely responsible for the Black Renaissance in letters, first in the 1920's and later in the 1960's; they were also, to a great degree, responsible for a regional hegemony over Black cultural artifacts which succeeded in directing the course of Black literature, not always towards laudable ends.

The Black novel might serve as an illustration. It began as a northern genre, created for the most part by exiled Southerners. William Wells Brown and Martin Delany were southern born, Brown a slave, Delany a freeman; both, however, fled from the South, from terror and oppression, and with the northern-born Frank Webb became the first novelists in America of African descent. Among them, they accounted for four novels: Brown's Clotel (1853) and Miralda (1861), Delany's Blake, Or The Huts of America (1859) and Webb's The Garies and Their Friends (1857). Each novel was imbued with protests, and those of Brown and Webb depicted images of Blacks modeled upon eighteenth and nineteenth century white stereotypes. Delany, the notable exception, modeled his characters upon rebellious Blacks, upon such paradigms as Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey. Their characters, however, were dedicated to overcoming oppression and tyranny and each maintained a proud dignity.

After the Civil War, the creative impetus which produced the Black novel shifted from North to South. The most talented of the novelists, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charles Chesnutt, and Sutton Griggs, toiled in the southern vineyard and no matter how distorted the portraits, painted their men and women from those who inhabited the rural and urban South. Dunbar's personal problems precluded realistic evaluations of the life about him; the result was that in too many instances, his characters are less representative of Black Southerners than they are of men and women created from the furtive imaginations of white propagandists. Though Chesnutt and Griggs evidence similar influence by white propagandists, both rise above such influence and project images of the New Negro to come, modernize Delany's Blake, and bring forth into the twentieth century the aggressive Black, willing to lay manhood on the line against an oppressive society, determined to struggle for manhood rights. The southern-born Josh Green of Chesnutt's novel, The Marrow of Tradition is one such example. Bernard Belgrave of Griffs' Imperium in Impirio (1889) is another; and even young Joe Hamilton of Dunbar's Sport of The Gods (1902) emerges as a man/rebel intent upon breaking the mores and folkways of a tyrannical society.

The New Negro, therefore, was born on southern soil and if not for the great migration, might have reached a maturity solely lacking to the present day. For the cultural and literary exodus meant the breaking of ties, the loss of roots, of place —a central setting upon which the creative imagination might be anchored and nurtured. To be capable of capturing the southern life style of a people in moments of tranquil remembrance was not enough; the break with traditions, customs and folkways must inevitably lead to cultural amnesia. The Black writers who came North were migrants, and all too often divested of visions of the past; they were Black men and women thrust upon alien soil and forced to create out of the marrow of an alien and threatening environment. There is little wonder, therefore, that the Harlem Renaissance was a period of cultural schizophrenia, one in which Black writers moved, helter-skelter, in all directions.

The major participants of the Renaissance were cultural/literary migrants. Johnson, Toomer and Hurston were from the South; Hughes, Larsen, and Dubois from the east; Walrond and Mackay from the West Indies. Though McKay is able to retain an emotional identification with his home¬ land in the novel Banna Bottom (1933), the Black novelist, for the most part, was unable to remember the cultural milieu from which he came and unable also to comprehend the new culture of which he and his people had become a part. Due to the loss of vision engendered by the loss of cultural roots, he was forced to create a literature which distorted the reality of Black life—one designed to appease the atavistic yearnings of a white and Black middle-class audience.

Alain Locke, chronicler of the Negro Renaissance, writing in The New Negro in 1922, championed the migration, the new writer who had emerged as a result and the new literature itself: "The day of 'aunties,' 'uncles,' and mammies is gone . . . The popular melodrama has about played itself out, and it is time to scrap the fictions, garrote the bogeys and settle down to a realistic facing of facts.... A main change has been, of course, that shifting of the Negro population which has made the Negro problem no longer exclusively or even predominantly southern .... In the very process of being transplanted, the Negro is becoming transformed." On the other hand, Benjamin Brawley, a much more perceptive and abrasive critic, realized that the transformation bordered nowhere upon the idealism inherent in Locke's writings and perceptions: ". . . but while Uncle Tom and Uncle Remus were outmoded, there was now a fondness for the vagabond or roustabout, so that one might ask if after all the new types were an improvement on the old."

"The new types" were paradigms constructed in Nigger Heaven (1926) the novel published by Carl Van Vechten. Here are new images of a northern urban people: sweetmen, pimps, sensation seekers and hustlers; Black men and women, who, in Norman Mailer's phrase twenty years later, subsist ". . . for their Saturday night kicks, relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body . . . ." Such images were adopted by some of the ablest of Black writers, by Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Rudolph Fisher; their existence in Black literature was tolerated by the leading Black critics of the day, of whom Alain Locke was most representative.

The acceptance of such images reflects the effect of cultural shock and loss; it is a manifestation of the severity of the migration which forced men and women away from their source of creative inspiration, cut them off from the reality of the Black existence and forced them to adopt a new truth in a new cultural setting, to look at Blacks through lenses fashioned in a northern urban environment. With varying exceptions the literature which results is escapist, always fantasy-ridden, stereotypic and distorted. The southern heritage of trial and endurance, of the existential struggle which produced the heroism of Josh Green and Blake, the determination of a people to prove their valor against tyranny and oppression becomes subsumed under the search for eroticism and exoticism, for the life style of the hip and the cool, for the atavistic yearnings more germane to white than to Black culture.

Furthermore, a regional hegemony which persists still became manifest. The publishing companies, all white owned, were up North; Black critics plied their trade in journals, northern based and dependent upon a white and a middle-class Black reading public. Racist America demanded that the reality of the racial problem be fictionalized, and that Blacks be viewed not in heroic battle against the society, but in the pursuit of sensual and material objectives; aggressive images such as those of Josh Green and Blake were to be supplanted by those like Jake of Home to Harlem and Jim Boy of Not Without Laughter. The great migration which sent a people into a quest for freedom landed the Black writer in a bondage from which he has yet to escape.

The publication of Native Son by Richard Wright in 1940, at first glance, may tend to negate such assertions. Though the novel rescued Black writers from sensationalism and escapism, it did not move them towards explication of the realities of Black life; like its predecessors, it was marred by the influence of white propagandists. Despite the high acclaim in which the novel is justifiably held, to read Native Son at this juncture of Black history is to be in the midst of a people sans culture and history, one whose roots are not those stretching back beyond the diaspora, but those which begin and end in a northern urban setting. Bigger Thomas, the son of migrants, is the true migrant; he is an American creation —a desperately driven man, deprived of that strength which fueled Douglas and Garnet, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman; he is one who has lost all cognizance of a previous history, who has become man alone, existing in an incomprehensible universe, robbed of the knowledge of that culture which served his ancestors.

Thus he is one of the two major paradigms handed down from Black writers of the past. Both are creations of a northern imagination, and both are representative to Black and white audiences alike of the twin dichotomies of the Black psyche: Bigger Thomas or the Scarlet Creeper: nihilism, overwhelming frustration and anger, or the hip/ cool life style of sensationalism and atavism. These are the offerings of the sons and daughters of those who began the great migration. Both are antithetical to Black history and culture, and yet they are the mainstays in the works of some of our most talented writers, offered in literature, upon stage and screen, as representatives of Black men and women, of their hopes and aspirations.

What then of the southern legacy? What of a set of values which taught a people to endure with dignity? Such offerings, to be sure, are to be found in the works of some Black writers. Jean Toomer and Zora Hurston are examples. The early part of Cane is a testament to the strength and endurance of a people and serves, with the second part, as a fictional example of what happens to a people who have lost a sense of the cultural milieu from which they sprang. The men and women of Zora Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God exhibit the courage and dedication to survival so much a part of Black history, past and present. Such novels were the exceptions, however, not the rule, and they were buried under the popularity of their more sensationalistic contemporaries.

The same is true of John Killen's novel YoungBlood which evidences southern heroism and courage with a depiction of Black people engaged in a never ending battle to overcome the strictures imposed by a tyrannical society. The novel was published during the period when Baldwin and Ellison were elected by the white literary establishment as ambassadors from the Black world to the white, and when such images as those personified in Invisible Man, Another Country and Manchild in the Promised Land were accepted as authentic representatives of Blacks. These were accepted despite the fact that YoungBlood was only the fictional representative of the courageous young people who marched with Martin Luther King, who chanted "Black Power" with Carmichael and Brown, who left heroic footsteps in the dust-caked towns of the South and the asphalt paved streets of the North as well.

The advent of the "New Black Arts Movement" in the 1950's engendered the hope that such cultural and literary sleight of hand by Black writers and the white literary establishment might be ended. The young people who followed the lead of Baraka, Fuller and Askia Toure were eager to step outside of American history and culture; they were ready to recreate the images and paradigms of old, to forge from the past the heroic legacy left by men and women who struggled unceasingly against the American Caesars. They were intent upon producing a new kind of Black literature, of offering different, more positive images. Their failure was magnanimous and not attributable to their dedication or their tireless zeal and energy. The problems resulting from the great migration remained as pressing in 1960 as they were in 1925. The lack of Black cultural institutions, of magazines and publishing houses, meant that cultural hegemony over the artifacts of Black people was still held by the oppressor; that white editors, like those of the New York Times Review of Books, still had the power to determine that YoungBlood was less representative of young Black men and women than Rufus Scott and Bigger Thomas; that competent Black writers like Paule Marshall, Ernest Gaines, Louise Merriwether and William Melvin Kelley were of lesser status than those who, in their works, depicted Black men as natural enemies of Black women, Black people as the major antagonists of Black heroes, and the American society as a benign, if not benevolent, society.

It is, of course, too late for speculation. Still, one is tempted to ask in hindsight, what might have been the status of Black literature had the migration never occured? Had men and women never forsaken the moral and ethical teachings of their southern ancestors, never become hypnotized by the materialistic offerings of northern whites, never lost that sense of morality and decency which served to distinguish, in sharp terms, the victim from the victimizer, would not our literature and our lot be better here among the barbarians?

One turns to the works of Killens and Gaines, Alice Walker and William Kelley for partial answers. Visions of a moral universe are still found in their works, of a place where people retain moral imperatives, where the prostitute is one who trades upon the misery of her people. Their men and women are paradigms of forced exiles from another land, who created a culture and history, artifacts and a life style to distinguish them from the arch-enemies of humanity. They possessed a love for life, a fidelity to the sanctity of the human spirit, a belief in the elevation of the human condition. Such people once walked among us, primarily along the dusty roads of the South and are still, as Toomer noted, a people upon whom "the sun is setting, but has not yet set"; hope, belief and faith persists despite all, and the young people in the colleges and in the streets who have novels, poems and plays flowering in their consciousness may yet forsake that migration of the mind which ruined many of their predecessors, may never become strangers to their history and culture, may remember Sterling Brown's admonition to old John Henry: "We had it once, John Henry, help us to get it again."

Tags

Addison Gayle

Addison Gayle, Jr., is the author of The Black Aesthetic; Black Situation; Black Expression; Bondage, Freedom and Beyond: The Prose of Black Americans; Oak and Ivy: A Biography of Paul Laurence Dunbar. His current work The New Way of the New World is a collection of essays on the Black novel in this country. Originally from Newport News, Virginia, Brother Gayle now lives in New York and is Associate Professor of English at Baruch (CCNY). (1975)