The Struggle

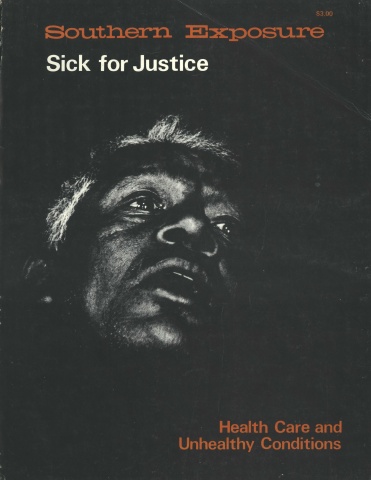

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

A struggle now rages within me.

It is the struggle of transformation and of resistance, of human necessity and human isolation.

It is a struggle which pierces the depths of my being, and one which I have not been able to resolve.

It is a struggle which is slowly destroying me.

I often thought about that struggle while standing in my shower, eyes unopened, lips parted, body drenched and warmed as water pounded upon my head. A certain faith and a measure of inexperience had enabled me to move aggressively and ambitiously through medical school — faith and the conviction that so long as I was skilled and devoted, I could lend assistance and relief to others, and serve them responsibly in a way which would assure mutual fulfillment. The key to both society’s well-being and my own individual happiness was above all a tactical matter requiring a certain emotional readiness and long painful hours of study.

But reality had weakened my firmly held convictions. It soon became clear that any service I could provide was merely symptomatic and short-lived, too little too late. The health of my patients was shaped by societal forces over which I had no control, of which I had little understanding. Neither I nor my patients could find any lasting satisfaction in such an arrangement, and as things stood, there was little hope for change.

Such distressing thoughts are not easily tolerated, and on this particular morning, I wiped them from my mind as I wiped drops of water from my arms and chest. In haste, I donned a stained white uniform, kissed Anne on the forehead, and for my breakfast, ate a plum on the way to the car. The engine turned over immediately (this always lightened the day’s burdens), and in no time I was headed for the hospital.

It was later than I had first thought, and after parking, I slung my knapsack on my shoulders and ran (slowly, in order to maintain composure) to the main entrance, already bustling with activity. A security guard guiding a young child in a wheelchair swung the front door wide, allowing my passage as well. Sliding past three nurses I moved breathlessly to the elevator, only to find it tightly sealed, leaving me to shuffle my feet stupidly and glare at the flashing lights.

The elevator door finally opened and I stepped in to find two elderly black ladies, one toothless and smiling, plaited and wrinkled, the other rotund and grey-headed. They were draped in drab yellow cotton workshirts and were clutching mops and pails of soapy water. Their nametags read “Environmental Services.” Their intimate chatter ceased abruptly when I entered.

The integral parts of great medical institutions move deliberately and with purpose. This elevator was no exception; it was programmed to stop at each and every floor whether or not anyone wanted to get on or off. Thus there was time for a conversation, though it was highly unusual for one of us to converse with one of them. I am not sure why this was so, though a friend had once explained that she simply couldn’t understand them, nor they her. Nevertheless, the toothless one continued to smile at me and I was forced to say, “How y’all doing?” She replied wryly, “Well, two people vomited up on Halsted ward, and one of the toilets on Sims overflowed. The day ain’t looking so bright.”

Her lack of restraint surprised me; I was not accustomed to such candor. Still, hers deserved a response. “I know what you mean,” I said. She shook her head and laughed heartily, in a way which only confused and embarrassed me.

We had reached the fourth floor and I walked quickly out of the elevator and down the hall to the nursery. Two medical students, an intern and the staff physician were waiting when I arrived. I quickly gathered my notes and we began walking the rounds of babies born on the previous day. The first two admissions were relatively uninteresting — two active full-term children; Baby Boy Taylor was different. He was small, floppy, and had the slanting eyes and facial features which we recognized as typical of Mongolism. The staff physician expounded upon the nature of this disorder, referring to the boy as the “Little Down’s,” and concluded by stating emphatically, reverently, “Mongols have a variety of problems, but they are all retarded, and they all look alike.”

We decided to visit and talk with Mrs. Taylor, who was watching television in her room. She was a thirty-eight- year-old Lumbee Indian woman who had spent her life in eastern North Carolina. Her skin was the color of crimson and slate; she had long, straight black hair and a quiet but firm voice. This baby was her sixth child; she was accustomed to uninvited physicians and well-meaning “student doctors.”

The staff physician spoke first, smoothly.

“Hello, Mrs. Taylor. We’ve come to speak with you about your little boy. Have you seen him yet?”

“Yeah, ain’t he pretty? I’m gonna name him Johnny after his father.”

“We have certain concerns about the child.”

“There ain’t nothing wrong with him, is there?”

“He seems to be doing relatively well now, but. . . ”

“That’s good.”

He spoke more sternly and slowly. “But we are concerned that the child is quite small and floppy, and is a slow feeder. We are not certain now, but there is a strong possibility that his psychological and motor development will be significantly delayed as he matures.” He paused for a moment and then continued, “He will very likely be a happy, playful child, but a slow child, slower than other children his age.”

She looked at him solemnly. “Slow.”

“Yes.”

After a minute of silence, “I’m not sure about all of what you doctors say, but I think he’s pretty, and I want to take him home and nurse him. When can he go?”

“In another day or two. We’d like to watch him for awhile. Dr. Freemark will be back to speak with you again soon. Try to get some rest.”

“Okay.”

We discussed the problem outside her room. Again the attending doctor spoke, understandingly, with concern and a bit of a smile.

“Her psychological defenses are difficult to penetrate. She utilizes her strong maternal instincts in order to drive real conflicts from the domain of consciousness.”

We nodded perfunctorily.

“She’s obviously of limited intellectual capacity, and at times these people have difficulty verbalizing or even understanding their own emotions. She may never come to grips with feelings like anger and guilt which lie beneath the surface.” T

he rest of the morning was uneventful. We stood by uselessly as an otherwise healthy child was delivered by Caesarian section. I spent two more hours plodding through my talk, “taking care of your baby at home,” for each of seven new mothers who were soon to be discharged.

Lunchtime was fast approaching and, to avoid the rush of humanity and the long lines in the downstairs cafeteria, we decided to dine on the third floor with the other doctors. As we filled our trays, I noticed that the intern with whom I had made the morning rounds was unusually quiet and visibly upset. When we sat down, I asked him what was on his mind. He blurted out angrily, “It’s just infuriating. This woman is thirty-eight years old, on Medicare, and has her sixth kid who’s a Mongol. She thinks he’s pretty now, but in a few years she’ll turn him up for adoption or institutionalize him; and you know who’ll be paying for it.”

“Oh, knock it off. People like her put you on the map.”

“She’s a leech. And when a leech takes hold and starts to suck, you’ve got to rip its head out before it drains you.”

“She seems to love the kid.”

“She doesn’t know what love is. Love is having a kid you can support with your own money. She just loves getting screwed and doesn’t want to know any better.”

“You’re full of shit.”

“Ahh!” waving his hand contemptuously.

In order to maintain good working relations, we avoided discussing the subject further. That afternoon, I returned to Mrs. Taylor and found her sobbing quietly. When I sat down by her bed, she reached out and lightly touched my arm.

“My baby ain’t right, is he?”

I shook my head slowly. “No.”

“I knew it from how the doctor was speaking to me, in ways I couldn’t really understand. I knew it myself when I saw him the first time; he didn’t cry like my other babies.”

Her eyes suddenly grew dark and driven. “I raised five young ’uns to where they could make it on their own. This one ain’t no exception. Different or no different, he’s mine. I ain’t had much luck in my time, and some of what I deserved I never got. But what’s mine I earned, and ain’t nobody gonna take it from me.”

As I sat staring at her, I recalled again the words of my friend. She had been right — I really couldn’t understand them. I feared their desperation and their power; their world was too intense, too real. More than anything I wanted simply to leave Mrs. Taylor. I rose, and moving slowly to the door, opened it awkwardly. “Goodbye,” I said, “I wish you well,” and walked down the hall, empty and alone.

Tags

Michael Freemark

Michael Freemark is a pediatric resident at the Duke University Medical Center. (1978)