This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Despite the flurry of interest in and assertion of ethnic identity which emerged in the 1970s, the process of cultural homogenization inexorably progresses — in the South as well as in the rest of the nation. Like many other Southerners, I view this transformation with regret. I am especially attuned to the changing character of the region because of my work as director of the Office of Folklife Programs of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. My job is to promote public awareness and appreciation of North Carolina folk culture. It seems plain to me from years of conversations with this state’s folk artists that a breakdown is occurring of the traditional culture of the South — an inevitable consequence of greater mobility, urban development and the growth of mass communications.

The South is by no means a monolithic culture zone. I am continually amazed by the diversity of expression within my own home state. But one overriding characteristic serves to unify the region culturally and it especially saddens me to see this weakened: Southerners’ extra measure of respect for the spoken word, a special love of the verbal arts. One hears evidence of this strong oral tradition everyday, in rich dialects, accents and cadences. Words, and the skillful use of words, seem less a means to an end than objects of pleasure in themselves.

The authors of the articles and stories in this section offer their thoughts on a prominent and precious feature of Southern oral culture — storytelling. At the heart of each piece lies the author’s recognition of the importance of the storytelling tradition in his or her development, along with an expression of deep concern for the survival of this vital part of our regional personality.

Bobby McMillon and Alice Walker give us passionate personal accounts of their relationships to stories and storytellers. McMillon, here writing down his thoughts on storytelling for the first time, provides an eloquent, story-like rumination on his deep love for the art and, along the way, surveys some of the storyteller’s intricate skills and techniques. His focus is on the storytellers who have meant the most to him: those everyday people from his community who entertained him and countless others for hours on end with their tales. Alice Walker, from a different but no less moving perspective, tells how Joel Chandler Harris, the creator of Uncle Remus, and Walt Disney, who put Uncle Remus on the screen in his film “Song of the South,” effectively destroyed the meaning and beauty of a great part of black oral culture for her and for countless other black children. Her testimony, along with Zora Neale Hurston’s folk tale, attests to the centrality of storytelling and the oral tradition in Afro-American culture.

In Jill Oxendine’s loving sketch of Kathryn Windham, the noted collector and teller of tales, we hear the words of a professional storyteller who has been at the forefront of the recent effort to preserve the storytelling art. Included with this piece is a discussion of the National Association for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Storytelling and Windham’s own version of the well-known tale “Railroad Bill.”

Finally novelist David Madden recounts his childhood experiences as the neighborhood storyteller and discusses the significance of storytelling to his fiction. To illustrate his points, Madden includes excerpts from his autobiographical novel, Bijou. These excerpts remind us that much of the best Southern literature has roots deep in the oral tradition.

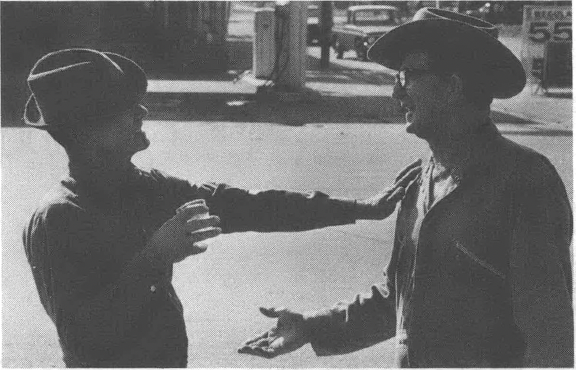

Perhaps the essential fact about storytelling to be distilled from this collection of essays and stories is that the significance of the art lies not so much in the content of a particular story — that which may be recorded or written down — but in the very personal and special relationship of the teller to his or her audience. The full meaning of this relationship may be beyond our abilities to put into words, though we know that somehow it is of fundamental importance to our humanity. In a world increasingly dominated by the printing press and electronics, the meaning of that relationship is certainly worth pondering.