This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 3 No. 4, "Facing South." Find more from that issue here.

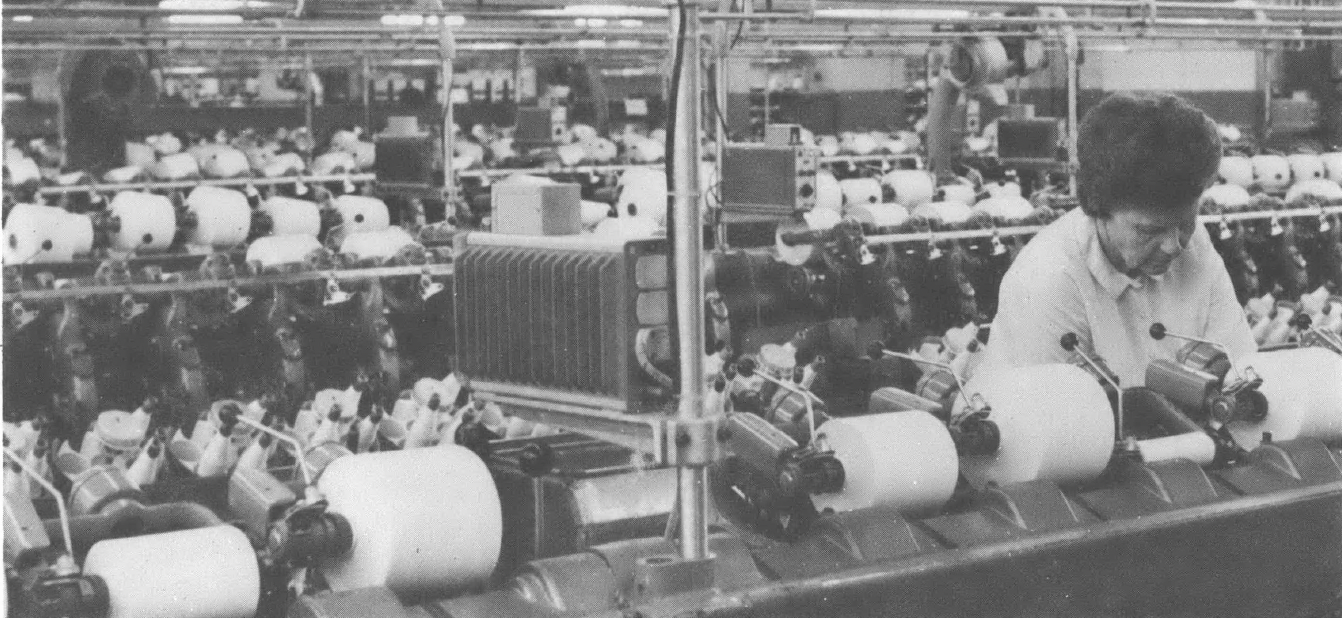

It is still possible in the South to find three generations of a family living in the same area, working over half a century in the same industry. This is particularly true of cotton mill work. And, because the textile industry has traditionally employed great numbers of women, families exist in which mother, daughter and granddaughter have all worked in one area's mills.

Martha Simpson, for example, first entered textile mills in Carrboro, N.C. in 1908, when she was just nine years old. She later moved to another mill town where her daughter, Fay, began work in 1930 at age 16. Another 22 years later, in 1952, Fay's daughter Janie, like her mother and grandmother, went into the mills, getting her first job at age 18. Together they have seen vast changes in textiles. Technology has developed rapidly. Unions have come and gone and are coming back again. Management has moved from friends of the family to distant boards of directors. The mill towns where the Simpsons lived have grown into diverse cities. Social relations inside the home and factory have undergone a major transformation. Independence and freedom have shifted from a matter of doing things for yourself, the self-sufficient family, to earning enough money to buy services from others. Gardening has become a hobby instead of a necessity. Child care has changed from the responsibility of older relatives to hired baby sitters. Husbands have begun to share more household chores. The place to socialize switched from the mill and the neighborhood to civic organizations. And through it all, these three women worked in the mills and changed their ideas of themselves and their work.

Martha

Carrboro's textile history begins in 1899 when the first mill opened. At that time, the town was distinguished only as the home of the train depot serving the nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The mill owner, a local farmer who had accumulated some capital operating a grist mill and cotton gin, built houses to attract his relatives and other families into town. By 1909, the mill had grown to 125 workers, and the original owner sold out to General Julian S. Carr who already operated several mills in Durham, 15 miles away.

Carr left the employees undisturbed, preserving the original feeling of being among families, neighbors and friends. Overseers and workers attended the same church, lived next door to each other, sent their children into the mills and intermarried. Together, this first generation saw themselves as a thrifty, hard-working people building a community in which they might all prosper.

Most millhands came to Carrboro from nearby farms, primarily for two reasons: a farmer's crop failed and, having nothing to fall back on, he took his family to the mill village for shelter and work. Or the father of the family died, leaving a widow who would move to town where her children could find “public work," i.e., wage-earning employment. Eventually others —including Martha Simpson's parents —moved in from the county to get closer to their stores or jobs in a growing Chapel Hill. Martha's father operated a blacksmith shop there, and shortly after they arrived in Carrboro, the mill owner asked her mother to take on boarders—single women who spent the week in town and returned to their parents' farms for the weekend.

When Martha reached age nine, she went to work in the mill, turning stockings inside-out for 50 cents a week, plus a nickel for Sunday School. Her brother, age 13, and sister, 14, had already been working there for several years. “My mother couldn't stand the thought of playing all the time," she says. "She was a worker, and couldn't stand to see me romping around."

As a small child, Martha was allowed to come in later in the morning than other children and adults, but as she grew older, she was assigned to more difficult jobs. In her early teens she earned 40 cents a day as a topper, putting material on the machine which sewed tops on socks.

Discipline was informal during these years, and the overseers often acted as much as surrogate fathers as supervisors. Children were allowed to go outside to play if it snowed or rained, but if the thunder and lightning frightened them, the overseer would gather them together inside and turn off the machines. The girls often sang hymns while working, and when they caught up with their jobs, they could sit in the window and talk with friends. “When I first went to work in the mill," Martha says, "I didn't work. I played. They don't do that anymore."

At lunch, the children walked home (with their fathers, if he worked with them) to a meal prepared by mother: milk and butter from the family cow, pork from the pigs kept in the woods by the railroad tracks, canned vegetables from the garden. In fact, for the mother in the typical family, life was much as she had known it on the farm: churning, keeping the chickens, milking the cows, tending the garden, making clothes, caring for the children. Martha recalls that her mother performed all these chores, took care of an invalid daughter and provided for the boarders. "She was the workingest woman I ever heard tell of. . . . Very smart and very industrious." Having come off the farm, women and young girls expected to work hard to provide for their family's livelihood.

On the eve of World War I, when she was 15, Martha married Larry Simpson, a fellow mill worker, and became an adult woman. For the next several years, they travelled throughout North Carolina looking for better work and more wages, while their first born child stayed with Martha's mother in Carrboro. "He was kind of a gypsy," Martha says of her husband. "His brothers would write him they had a good job and then when we got there they'd move somewhere else."

After the war, the Simpsons settled in a mill town not far from Carrboro and began working in the locally-owned mill, Martha as a spooler earning nine or ten dollars a week, Larry as a loom fixer making $19 a week. Each day, they walked to the plant together, worked near one another and socialized with friends and neighbors who were co-workers.

The physical situation, however, was much worse than it had been in Carrboro. "That was the nastiest mill that I ever went in and ever heard of," says Martha. "The toilets (were) filthy, and dirt. . . . People spit on the floor, they never swept the floor. It was awful." Everyone drank from the same dipper in the same bucket, which helps explain why epidemics, like the influenza outbreak at the close of World War I, spread rapidly. Cotton dust and lint filled the air:

"I've seen where the sun would shine through the window and I'd see great gobs that big. You couldn't see it unless the sun was shining. ... I had it in my eyes, my hair'd be white. And my eyelashes . . . when I'd wake up in the morning, my eye could just be like that and (I would) just pull strings out of it."

Martha and her husband rented a mill house with an outside communal toilet and spigot and, like their parents, they got most of their food from a garden and a few farm animals kept near the house. Each evening, Martha would leave the mill an hour early —with the overseer's permission—to start supper for her growing family. When one of her five children was born, she would leave her job until they were about six weeks old, then return to work while her mother or the older children cared for the baby. She recalls that her husband took more responsibility for household chores than her father had done, but it was still a rigorous life, combining the duties of a self-sufficient mother with the full work load of a millhand. Today, Martha takes a certain pride in the fact that she succeeded without the help of modern conveniences, and points out with some regret that she was the last generation to remain independent of store-bought goods. Her children, she says, “didn't inherit any of that frugal living from me. They got big-headed. I got one daughter, she works herself to death. . . . Her husband's smart, and he likes the garden and chickens and hogs and things. (But) she never sees the hogs. . . . And when they want vegetables, if he don't pick them and bring them in, she goes to the store and buys them. Don't have time to mess, she tells him not to do it."

Fay

In 1930, Martha's oldest daughter, Fay, was 15 and nearly through high school. But the Depression hit town (“knocked it deader than a doornail," says Fay), forcing her to quit school and enter the mill with her parents. They were happy to get two or three days of work a week since many mills— including the one in Carrboro —closed down altogether. “We thank Mr. West for that," Fay says in typical appreciation of the earlier paternalism. “At least we didn't starve. . . . Mr. West kept hanging on and hanging on until he had almost the entire bottom floor of the mill packed as high as it would stay with baled cloth." Eventually, however, West went bankrupt and sold out to a family which had extensive financial connections and a chain of mills.

The new owners brought a different system of management to the mill which has helped the parent company become among the industry's top producers today. They had enough money to “ride out" the Depression, and when the market for cotton goods began climbing, they introduced the “stretch-out" to increase the mill's profitability. “Where you had three on a job," Fay explains,

“they'd stretch it out and two would be on a job, and they'll stretch it out (until) some of them have only one on a job." Gradually, they decreased the 12-hour day to ten, and finally “instead of completing a day's work in ten hours, they had to fix it so it would work in eight." Three separate shifts were begun, and while the worker was in the mill a shorter number of hours, the work was considerably more intense.

Fay remembers that people had very little recourse in the face of such changes: “People here were very grateful for their jobs and some of the bossmen held it over their head. You know, 'You come in and work, or somebody else will get your job.' Well, that was the truth and everybody knew it because where you had a job, probably a dozen other people could run that job as well as you could, standing out there waiting for it."

A long-standing division of work by sex gave men more freedom to come and go during the day, but the new owners slowly initiated tighter security, finally locking the workers inside the gates. "Grown men," says Fay, “would go swimming; they'd go to the theatre, come back and get their work done, and maybe hook a train and go to Mebane to the fair. . . . And at night, I know my husband didn't miss a single change of theater down there for years because he'd catch up with his work and go to the show two hours, come back, catch up at eleven o'clock and go home. . . . The women mostly stayed there and kept the machines running. . . . They used to go out to the cafes and eat, or go out and buy things and drink Coca-Colas. Well, (a relative of one of the workers) started with a little wagon and went through the mill bringing in drinks and sandwiches and stuff.

The wagon would come in there two or three times a day, and people would buy their Coca-Colas and sandwiches and candy bars. (And then the mill owners complained that) there was a whole lot of vandalism going on. So they got to just closing the gates."

In addition to creating a new sense of fear, these new techniques also destroyed the natural camaraderie and easy friendliness between the workers, particularly the women. It was still possible to talk with fellow workers in the 1930s, but in the early 40s the introduction of faster and louder machinery made conversation nearly impossible. Reflecting on these changes, Fay says: "They'd been speeding up the work till you didn't have time to talk, and I think they made a bad mistake with that. As long as you give the workers time to maybe possibly crack a joke or tell something, they're a whole lot more interested in working than they are in just being robots. And I think a whole lot of something has been lost now, people taking pride in their work."

A year after Fay began work, she married an 18-year-old millhand and began having babies. Unlike her mother, she left the mill for several years while her four children were young. But in 1942, "when the mill started up full blast" with government contracts for finished cloth, she joined her husband on the third shift. She viewed her independent income as a source of freedom from a husband who was basically unhappy with the responsibilities of being tied down with a family in his hometown ("he was just doing a teenage revolt").

Other experiences gave Fay a different view of women's rights than that of her mother. For example, when her husband and other male workers went to war, Fay recalls with pride the resourcefulness of the women: "Women almost kept the mills going and everything else because all that bunch of boys and men they had down there that were of draft age were drafted. I really didn't realize that there were so many men gone until they all came back. You missed a face, and you knew a boy had gone in . . . but it really didn't dawn on me til they came back in actually how many were gone."

Fay continued to work the third shift after the men returned and to take care of her children, though she had some help from a black housekeeper in the afternoons. She didn't have time for a garden or livestock, or even many friends; her husband, Ed, failed to offer much help. “I've often wished I was a man because I thought I could change the situation a little bit," she laughs, “and maybe sometime when Ed would make me good and mad I'd wish I was a man like him just so I could beat the tar out of him. (But) it's kind of futile. I think it's entirely stupid to keep butting your head against a stone wall. I don't care how much I want to be a man, there's nothing I can do about it. . . . It's like a woman getting pregnant; it didn't care whether she wanted to have that baby or not, there wasn't much choice about it. She was going to have the baby. Of course, they don't do that too much nowadays.

Janie

Fay's daughter Janie carries many of her mother's ideas another step further. On the one hand she articulates a traditional sense of fatalism about her position as a working class woman; on the other hand she is in many ways the first generation to assert some control over her life through such “modern" means as divorce, family planning, unions and political organizations. For example, Janie, too, was married at 16, but when she saw the marriage was a mistake, she went into the mills "to earn money for a divorce" —before she got pregnant. Fay had not wanted any of her children to work in textiles because “it's dirty work going on, and you always see favoritism. ... All the bossmen and straw bosses had women down there in the mill belonging to them, and they were the one that got the snap jobs." To Janie, however, there was very little option, given her education, sex and economic background, except going into the mill:

"We went to school, the farmers' children and the mill children more or less over here, and your uptown children were over here. . . . You were taught in the same classroom, but you could tell even as a child that you were not given the attention that the uptown children were given, and so, you know, that bothered you, too. The blacks talk about segregation. I know what they're talking about. Not as bad as they have had it, really, but, in a sense, we were sort of segregated. ... So I never really thought about (what I was going to do when I grew up) because I knew that the circumstances would prevent me from going to school and furthering my education. I learned quite young we're not poor-poor, but we're poor. . . . and I just never let it worry me or think about it. I should have, I suppose, because they say where there's a will, there's a way. But I still say it goes back to the way you're raised. Girls were more, 'You don't do things like that'. . . . Girls just can't go off and live by themselves—'nice girls don't do that'. . . . Thank the Lord education hasn't been limited to the elite and the rich anymore. If you want an education now, you can get it, boys and girls both. But, you know, girls didn't go to college like boys."

So when it came time to look for work, Janie followed her mother into the mill. It was close to home, required no special training or dress, paid well compared to what other employers offered 18-year-olds without skills—and perhaps more importantly, she had what she now calls "this complex: I didn't feel like I could get a job anywhere else."

In 1957, after a few years in the mill, Janie began a new life with a new husband who worked in the shipping department. They decided from the start that they would wait two years before having their first child, making Janie the first in three generations to allude to knowledge of birth control techniques. She quit work when her first baby was born and did not return until the second child was three months old. When she went back to the mill in 1963 ("because we wanted to pay for our home and everything"), she worked the second shift while her husband, Richard, kept his day-time job "so one of us would be at home with the children all the time." For the next eleven years, Janie says, "We never saw much of one another." She got up early, did the washing and ironing, cared for the children and left the evening meal cooked, ready for re-heating. A baby-sitter kept the children until Richard came home. He served them dinner, put them to bed and cleaned the house on Friday nights.

Today, the children are teenagers, and the couple has earned the money to purchase their own three-bedroom, tastefully-decorated brick home equipped with a dishwasher, washing machine, dryer and color television. "It's not a house to us," says Janie. "It's a home. To me there's a big difference." They have beef cattle in the field and a garden, but they are hobbies, not necessities. The old, isolated mill village has been torn down because the cost of repairing and modernizing the houses made them an unprofitable investment for the mill owners. Now Janie and Richard hardly know their neighbors except to say "hello" occasionally, but they are both active in larger civic organizations like the PTA and precinct Democratic Party.

To succeed in this new life-style, Janie and Richard have both been hard-working and thrifty— and both have left the mill, Janie for an office clerk job ("it's like a vacation"), Richard for a higher-paying, unionized position with a multinational corporation. Neither of them would like to return to textiles, and Janie specifically says, “It's nothing I would want my children to do. . . . It's an honest living and it's hard work . . . but I don't want them to work as hard as I did. .. . There's no future in it."

Janie talks at length about the conditions in the mill and why she left her top paying post as a weaver: "If you make production, you earn good money. But this means you ache on your job. .. . It's still that way today. You have no one to relieve you, to sit down and eat lunch, unless the guy that fixed your loom volunteered to run for you to eat. But it's eight solid hours of continuous walking. And you have no one to relieve you to go to the bathroom. If you wanted to make money, you stayed on your job eight solid hours. You made good money, but to me, it wasn't worth it."

The lint, humidity and noise made working unpleasant and conversation difficult: "You have to get accustomed to (the noise)," says Janie. "I think it took me two or three weeks to really get this roaring out of my head and get accustomed to walking in, and I did find that you learned to read lips a lot. I doubt I could do it now, but you know, you could talk to someone, although you couldn't hear exactly what they were saying.

"And the men, we found that they could goof off if they wanted to," Janie recalls, reflecting the resentments of the earlier generation. "And, of course, I guess we just took it as a matter-of-fact thing, you know, and some nights they'd have to work harder than others but a lot of nights, they were there. ... I don't sound bitter, do I?" she laughs. "I'm not, because I guess I was brought up, women did harder work than men any time. But that's changing some now. It amazes me that everything is changing, but sometimes I wonder if some of the women aren't taking on a little more than they should or can possibly take care of. But I guess they have confidence in themselves that they can do it, and they are doing it."

In addition to the loss of socializing at the mill, says Janie, pressures on the supervisors to increase production meant that the old attention to the workers' needs had to go: "I had a supervisor who didn't know how to deal with people. He didn't know how to talk; he would shout at them. ... He felt like they were uneducated people even though he was an uneducated man himself. . . . One particular night... I went to the bathroom. It was two o'clock in the morning, and I had not been. I walked in and used the bathroom and washed my hands and walked back out, and he was waiting on me. Oh, we had a few words. I walked away from him, I said, 'Don't holler at me; I'm a human being.'"

Janie's sensitivity to her mistreatment led her to become the first in her family to speak entirely positively for the rights of blacks and unions: "When I was growing up, I couldn't understand why the blacks had to sit at the back of the bus. I couldn't understand why they had to stand at a lunch counter to eat or take the food away. I didn't understand why they had separate bathrooms and ... I guess when all this (civil rights) came about, I was glad. . . . They're human and they deserve the same rights in this world that I deserve. They deserve a better education. If they're going to spend money, they deserve the right to spend it like I do. I don't see why they should be kicked back or pushed and say, 'No, you can't do this because you're black,"'

Textile workers, Janie believes, should begin asserting their rights and supporting each other like blacks did in order to win improvements in the mill. "I was really for a union," she says. If one had won in her plant, she thinks they would have had "decent salaries like other union plants, and I would have expected more courtesy, you know, and let's just say better working conditions." But as it turned out, Janie's pro-union sympathies pushed her out of the mill: "One night when we came out of work, there were union men at the gates. And they had their cards. And my neighbor across the street, she and I rode back and forth to work together at that time. He said, 'If you want, fill these cards out and hand them back to me tomorrow night. We'll be back again.' I said, 'Well, I don't think I'll wait til tomorrow night. I'll do it now.' And I did. Of course, there were the men from the office, the manager. . . watching. But really I didn't feel afraid. I thought, 'Well, this is what we need.' We really needed it. And they got upset because a lot of us went to union meetings. I only attended two, I think."

Workers who had attended the meetings were called into the manager's office and asked why they had attended. Janie told him that there were two sides to everything and that she went to the union meetings to hear their side. The manager assured her and the other workers that he would protect their cars against damage from the union men. He ended, "You will be at work. You will not let them scare you off, will you?" Janie was sure nothing had been said at the meeting about harming workers or damaging their cars. The notion of violence was invented by the mill manager.

After the meeting, she noticed that she was given the dirtiest jobs. Her supervisor assigned her to work on a set of dilapidated looms that nobody could make any money on. At the end of the week, she quit. Janie's children have not gone in the mill.

Tags

Valerie Quinney

Valerie Quinney, now teaching history at the University of Rhode Island, spent several months in 1974 and 1975 interviewing dozens of textile women with Hugh Brinton and Brent Glass under a project of the Chapel Hill Historical Society. The names of the women in this article have been changed. (1976)