This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 3/4, "No More Moanin'." Find more from that issue here.

The drive to organize the employees of the mighty General Motors Corporation culminated in the historic Flint sit-down of early 1937, but it began in a small branch assembly plant on the outskirts of Atlanta on November 18, 1936. Organization had rooted in the Lakewood plant in 1933 in the form of an AF of L “federal” local, but in common with so many of those hybrid unions which accompanied the National Recovery Act, the organization seemed doomed to impotence by its structure. As economic conditions worsened during Roosevelt’s lackluster year of 1936, the forces which had spurred unionization multiplied. The speed-up, determined by the demands of investors, was intensified while wage levels were unimproved. The seasonal character of the work militated against any job security, and the continued intransigence of management to any form of independent organization all contributed to the strike wave, both nationally and in Georgia.

While the AF of L local had disappeared when its fatal insistence on craft division had rendered it inoperative, the conditions which spawned it had not. The need for organization remained, the form presented itself in the creation of the CIO by dissident AF of L unions in 1935. Centered around John L. Lewis’ United Mine Workers, a variety of fledgling unions quickly spread tender organizational roots throughout the country, and Atlanta’s Lakewood plant joined the United Automobile Workers (UAW) as Local 34. In truth, only a handful of union faithfuls had joined the Local before November, 1936; but the participation of the entire work force in the strike showed that hearts, if not wallets, were in the right place. Holding out for over three months in the snowy winter of 1936-37, the mettle of the organization was well tested and gained rather than lost strength.

Why Atlanta, with no appreciable organized influence in the auto plant, should precede the industrial capitals to the north in precipitating the strike wave has been something of a mystery. Sidney Fine, in his “standard” work on the General Motors strikes of 1936-37, Sit-Down, gives credit to UAW General Executive Board member Fred Pieper for having called the workers in Atlanta out on strike. The following interviews reveal that the decision to stop work was a collective one and the influence of the national union was peripheral to both the call and the conduct of the strike. Fine seems to think that Atlanta was travelling under the illusion that a nationwide strike was imminent and that was the conclusive factor in their decision. While Local 34’s president at that time, Charlie Gillman, acknowledges that they thought the rest of the plants would come out soon, the local conditions were the dominant factor in the move to strike. This is underscored by the wide support the strike enjoyed among the work force even though union membership was miniscule in the plant. Push coming to shove was a far more decisive factor in Atlanta than Executive strategy.

Fine’s position is based on his source, the papers of Fred Pieper. His unfortunate reliance on the single account of a figure who seems to have been somewhat removed from the center of action during the Lakewood sit-down and subsequent picket is typical of the errors which have contributed to making academic history what it is today: an ideological commodity, baggaged with apologetics and bloodless inaccuracies.

But the labor movement, perhaps more than any other institution in our society, is a thing of flesh and bones, demanding a history of people, not individual leaders. This is particularly true in the initial stages of development, in that period when solidarity is not just a curious word, but a culmination of human values galvanized into action. It is in this interest that Southern Exposure presents these interviews—history from the bottom up.

Mr. Charlie Gillman was President of the UAW Local 34 at the time of the sit-down strike in 1936. A few years later, he went to work full time with the CIO to build a regional office and stayed with the AFL-CIO until his retirement in 1968. Mrs. Gillman is a staunch union supporter, and for almost fifty years has actively supported and conspired with her husband to build a trade union movement in the South.*

Here they talk about some of the conditons that led to the strike in the winter of 1936 and the significance of the strike in building the union.

Mr. Gillman: I was born in Birmingham, Alabama. We lived in Columbus and Augusta. We were married in Augusta, and then we came up here—during the Depression, wasn’t it, honey? Dad was a custom tailor, and mother, well, she was a housekeeper, but she would assist him in rough going.

What did you do when you first moved to Atlanta?

Mr. Gillman: Worked in the Fisher Body plant. As I remember it, it had been operating only a few months.

Mrs. Gillman: You know, it’s interesting how he got his job. They had a line of men out there looking for work, and the foreman—or whoever it was that hired people—came out and asked for somebody who could spit tacks. So he holds up his hand. He didn’t have any more idea of what they meant by spitting tacks than a cat did. But they took him in, and handed him one of these little magnetic hammers and tacks. They had to show him how to do it, and the man told him that anybody who wanted a job that bad could have it.

How many people were working in the plant when you started? How big was it then?

Mr. Gillman: I guess we had close to 900 people in the Fisher Body side, and about the same, maybe a few less, in Chevrolet. They were divided, you see. Fisher Body would build the bodies, and they would go over on one of these chain things through the wall to Chevrolet and they would put the motor in and finish them up. . . .

We just got kicked around. We formed a union out there because in those days when a fellow went to work, he had no security of any kind. He didn’t know if he would be working one day or the next, and as soon as the foreman had some member of his family out of work, why he would fire you and bring this family member in so he wouldn’t have to keep him up. It didn’t make any difference if you had a half dozen children, or a dozen, or none at all as far as they were concerned. They would just as soon fire you if you didn’t work as fast as they thought you should. The people just finally got tired of it, and the lack of security, I suppose, was the thing that really organized our plant. The fact that people just got tired of being pushed around.

See, what they would do, when they changed models, they would bring the people in and work twelve to eighteen hours a day, getting the new models ready. They would pay an hourly rate; I think at that time it was 45 cents an hour or something like that. Then when they had the dealers stocked up with new cars, they would put us on piece rates, and of course then we would only work two or three days a week.

I suppose we would rock along through the spring, until the spring season was over, working three days a week or usually less than that. But at any rate, we would work short hours like that until we got in debt again. And they always kept you in debt. They figured if you were in debt and owed everybody that you could owe, why then you couldn’t quit, or you couldn’t strike, or you couldn’t do anything to better your life. So it was pretty rough out there at those times.

You remember, under Roosevelt they had the NRA days, and they were supposed to have had the right to organize in those days under that statute and under that declaration. So we didn’t have any better sense than to think that they meant it, and we organized our union. We were ready then—we had built a good union about that time—and when things got so rough there, and they started kicking the people around, getting them to work faster, speeding up the line, we just quit. We pushed the button up in the trim department and shut the whole plant down. We just quit and stayed in there. Of course, we didn’t go out. We appointed caretakers from among the people to see that there was no damage or any violation of fire regulations or any security as far as the plant was concerned, and we had no problem at all.

We finally got an agreement out of Roach, and Gallaher—we brought him in too, from the other side, from Chevrolet—that there would be no effort made to try to operate the plant; if we would go out of the plant, they would shut it down. So we agreed, and we went out. The union hall was right across the street from the plant, and we set up a picket line and built tent houses there on the sidewalk and all around the plant, and our pickets just practically stayed out there. We put stoves in the tents; it was in the cold weather, and we just set there, that’s all.

The thing rocked along, of course, until the other plants shut down in the General Motors system. Ours was the first plant that went on strike. Of course, we were crazy. We thought at the time, we had been advised that some of the other plants were organized, but none of them were. The national union didn’t have any money. It was new, young then, and they didn’t have anything, so we had to get by the best we could. It was getting pretty rough too, after we had been out a few weeks, didn’t have anything to eat, didn’t have any money in the treasury or anything. So we set up what we called the food squad, the begging squad, and these fellows went out to the city market out here, and those farmers would give us bags of potatoes and onions and peas. I ate so many peas and onions I didn’t want to see any more for a while after we got through. I’m telling you what’s a fact, but they were good then. And we sent a couple of men throughout the automobile industry up north and chiseled some money out of them. Finally, when John Lewis moved in to run the national union, we was able to get some money out of them, and send around. We had a little bit.

One thing I remember, it was cold that winter too; it was right in the middle of it, January or February, ice all over the place, and we got ahold of Lewis and he had the miners ship us a carload of coal over from Birmingham. And that just about saved our day, I’m telling you, people were running low and our credit was about used up. The utilities were very cooperative, they didn’t shut off any lights or gas or anything. Most of the real estate agents let us back up the rent. And they were very nice too. We didn’t suffer any that way. The biggest trouble was we just didn’t have enough to eat.

Mrs. Gillman: You know, one thing that always stuck in my mind about that whole difficult period was that some of those people had seven, eight and nine children. We were more fortunate, we only had one. And you can imagine what a terrible thing it must have been for them not to have food for those children and milk was out of the question. And if you got hold of a quart of milk, you felt that you were rich. It was really a very difficult time, and I was often amazed that we stuck it out as long as we did, it was a long strike.

How did you relate to the national UAW once the plant went down and you began to see that other plants weren’t going to go down with you?

Mr. Gillman: Well, there wasn’t anything we could do but stay down. They kept promising—Homer Martin, what a faker he was—he kept promising, “Ah, we’re organizing, we’re ready to go, we’ll be ready, we’ll join you,” and they kept fooling around. They were organizing all the time, of course, but they had no semblance of an organization at all when we came down and struck the plant; we didn’t have sense enough to know that. It was like one little old plant here trying to shut down General Motors. But it didn’t take them long after we had started the thing down here. Most of the plants—Norwood, Ohio, Kansas City, and Buffalo—they all started and got right in the works, and very shortly we had all the plants organized. Of course the strike was over quite a while befor we finished the organization in General Motors—the shops, parts departments, and all that—but it finally was done, and there is no relationship between the working conditions and the lives of the people who work for GM now and what used to prevail in these plants.

I was going to ask you if you wanted to say anything about the UAW leadership when you went out on strike here.

Mr. Gillman: Oh yeh, Ed Hall, George Addes. Wyndham Mortimer, although he was a Communist they claimed, he was a smart one. He was the one that actually held the union together, to tell you the truth. He was the one that did the negotiating, he and Ed Hall. National contracts, and I believe that Addes and Hall and Mortimer did more to build this union after Lewis turned it over as a national union than anybody in the organization. Mortimer was a Communist, there is no doubt about it, in my opinion. But the thing is, Communists in those days were useful to the labor movement if you would let them do their job of organizing and get them out. But if you left them in they would tear it up again, too. But Mortimer was an exception. Because they used him to negotiate on the contracts, he was very seldom around in the plant. His job was primarily to negotiate the grievances, and he did a good job of it. Ed Hall, of course, was a big old blustery fellow, and he would holler and hoop; well, they would work together. Hall would pound the table and holler, and Mortimer would sit back and say let’s quiet down. Then the two working together would intimidate the management and then Mortimer would get the thing done. He was a good man. I liked Mortimer very much and always did while he was in the office.

Those three men, and Germer, Adolph Germer. He was an old miner, and he came with the CIO when John L. set it up. He saved our union down here, because we couldn’t get anybody to come down here. Martin was always busy flying back somewhere, and the rest of them had their own problems. So they sent Germer down here and he stayed around a month at the worst time, ’cause we had been on strike for two or two-and-a-half months or something like that, and he came in and stayed with us. He was a smart fellow, and people loved him. He died, of course, not long ago.

With the exception of Homer Martin, you had faith in the national UAW leadership, and felt they helped the strike?

Mr. Gillman: Yes, they were adequate, and Reuther came along a little bit after that. Reuther was a smart fellow, too. Didn’t agree with him all the time, but he was a smart person anyhow. His two brothers were smart, too. We had some very capable leadership at the top of the organization after they kicked Martin and his group out of there. Of course Martin got in by default ’cause we didn’t know anything about him. He was a preacher and he could make a good speech, and so they elected him at the convention at Pontiac. But the others—R.J. Thomas, Addes, Mortimer and Ed Hall—very capable people. . . .

The strike lasted about three or four months. The thing about it is, with the conditions we had, if we didn’t accomplish anything else, we established bargaining rights with the company. The first little contract we had just says that they will bargain for the members alone. And, of course, that didn’t work very well. As we organized over in the other plant, why of course we changed the contract. But if we didn’t do anything else, it brought those people together, and there wasn’t a single man in that whole 1200, or whatever it was he had in the plant at that time, made any effort to go back to work that entire time. And we were able through that strike to bargain for decent wages. One of the best provisions of the contract was that we had a committee of workers that was able to go into the plant and time-watch jobs, to regulate the speed that the people were working and to take some of the work off of them.

The first year of so of our contract, the committee had to handle grievances after they got through working eight or nine hours a day. They would have to go in at night with the management and negotiate the grievances. That was the first union, I suppose, in the city of Atlanta, that had to get out and fight to build an organization. There were unions here such as the Clothing Workers, but their contracts were negotiated at their headquarters: they was more or less from the top down. And the power company—the linemen were organized, and a few of the buildings and trades—but other than that, the people in our section here had very little knowledge about labor unions and all. That is true pretty well today, too, in many sections where the people are just absolutely afraid to talk to a labor person, afraid they will be fired from their jobs.

The union tended to bring the people together and give them a little pride. You know, so many people were just barely existing and not making enough to even eat on. They were losing some of their pride—the pride that people usually have to do better for their family, to have security, and to know that they will come in the next morning and go to work. That alone was worth the strike, if nothing else had been accomplished.

We were very proud of the accomplishments we made for the people out there in that shop, and we don’t apologize for anything that we did. Anything that we put in building that union was well worth it. All the people that worked there during that time will tell you now that there was no greater thing ever happened to them as far as work was concerned.

Mr. W. A. Cowan went to work for the General Motors Lakewood Assembly plant [at that time, in the Fisher Body Division] in 1932, and retired in 1967. Harvey Pike began working for Fisher Body in February, 1929, and left the “last day of February in 1966.” Between 1946 and 1950, he worked full-time for the regional CIO Southern Organizing Committee. Claude Smith first worked for General Motors in Norwood, Ohio in 1926, “built the first cushion” in the Atlanta plant, and retired in 1967. Tom Starling began working for Fisher Body in April, 1928. From 1941 until his retirement in 1968, he was on leave of absence from the plant to work full-time for the UAW, serving twelve years on the International Executive Board and fifteen years as international representative. Mark Waldrop came to work for Fisher Body in 1928 and worked there for five years, then quit and went into the grocery business “’til Hoover came along and taken everything I had but my shirt, and I had to go back to work somewhere.” He returned to Chevrolet for one year, and then moved to Ford where he worked for twenty-seven years. All five men were members of the fledgling UAW local at the time the sit-down strike occurred in November, 1936, and played key roles in the subsequent long, hard winter months of sustaining the strike and building a strong union.**

Could you give us some of the background leading up to the strike?

Mr. Starling: In August of 1929, there was a lot of dissatisfaction over working hours. What happened was we were supposedly on piece work, but you could barely make day work on piece work. We had no overtime provisions then, and you didn’t get paid a premium for working long hours. Where I worked in the Fisher Body paint department, they would run the line for ten or eleven hours a day and then there would be a lot of repair work to do on the bodies to finish them up. Quite a big group of workers would have to stay then, until 11 or 12 o’clock at night, to finish up that work. They were paid 35 cents an hour for overtime. They would have to be back to work the next morning at 7 o’clock, so it just went from bad to worse. We decided then, just the employees talking among ourselves, that we were not going to work beyond nine hours a day. I don’t remember the date, but it was early August. We decided that we would go home after nine hours at 4:30. We went to work at seven o’clock and got thirty minutes for lunch; 4:30 would be a regular day’s work. The company wanted the time to. run until 6:30—eleven hours that was. Then they came back just before 4:30, and said they would agree to shut the line down at 5:30, just work ten hours. We said no, we were not going to work over nine hours, so at 4:30 we quit and went home. When we come back the next morning, the management had pulled the cards of the leaders and fired them, so the employees refused to go to work. They went in the plant, but they wouldn’t go to work.

This was in August, 1929. We had a meeting in the plant and decided then that we would organize and we painted some signs of different types—one of them was demanding a dollar an hour and overtime. Then we formed a parade and paraded down to the labor temple. We had some speakers and set up a semblance of an organization. Had different departments to elect a spokesman from each department.

The AFL set up a committee among the AFL people and they met with management. The second day we were out, we all went back down to the labor temple to get a report. They reported to us that night that we would have to go back to work, that they were not prepared to take us into the union. The management had agreed that everybody could return to work with the exception of thirty people who they considered leaders in the movement, and those people would be fired. So the AFL advised us to go back to work the next morning.

When they named the people on the list to be fired, I was on the list. But I had worked with my foreman in Pontiac, Michigan, so he got ahold of me and told me not to come in, that he would notify me when to come to work. Then he reported me out absent because of a death in the family. A few days later he told me to come in, and told me what he had told them and that he would substantiate my story. So that’s the way I got back to work, and that was the end of the strike.

In 1933 a local union of the AFL was organized. We didn’t have very many members, but we had a local union. Then in 1935, the Chevrolet transmission plant in Toledo went on strike, which was the only Chevrolet transmission plant General Motors had, which naturally would shut down all the other plants. But we got together and decided that we would strike in sympathy with the Toledo plant. So we shut the plant down. I don’t remember the day, but it was in the spring of 1935. We were out for a month then, and when they ended the strike in Toledo, then we went back to work.

Mr. Pike: I’d like to point out since we brought in the old AFL, now we was under them in 1933, along in June of ’33, until about October of ’35. We left the AFL when the CIO was formed.

How strong was your union when it was an AFL union?

Mr. Pike: It was fairly strong. Like he said, we won the strike.

Mr. Starling: We continued under those conditions up until November 18, 1936. Actually our first incident happened on the 17th when they told the employees they couldn’t wear union buttons.

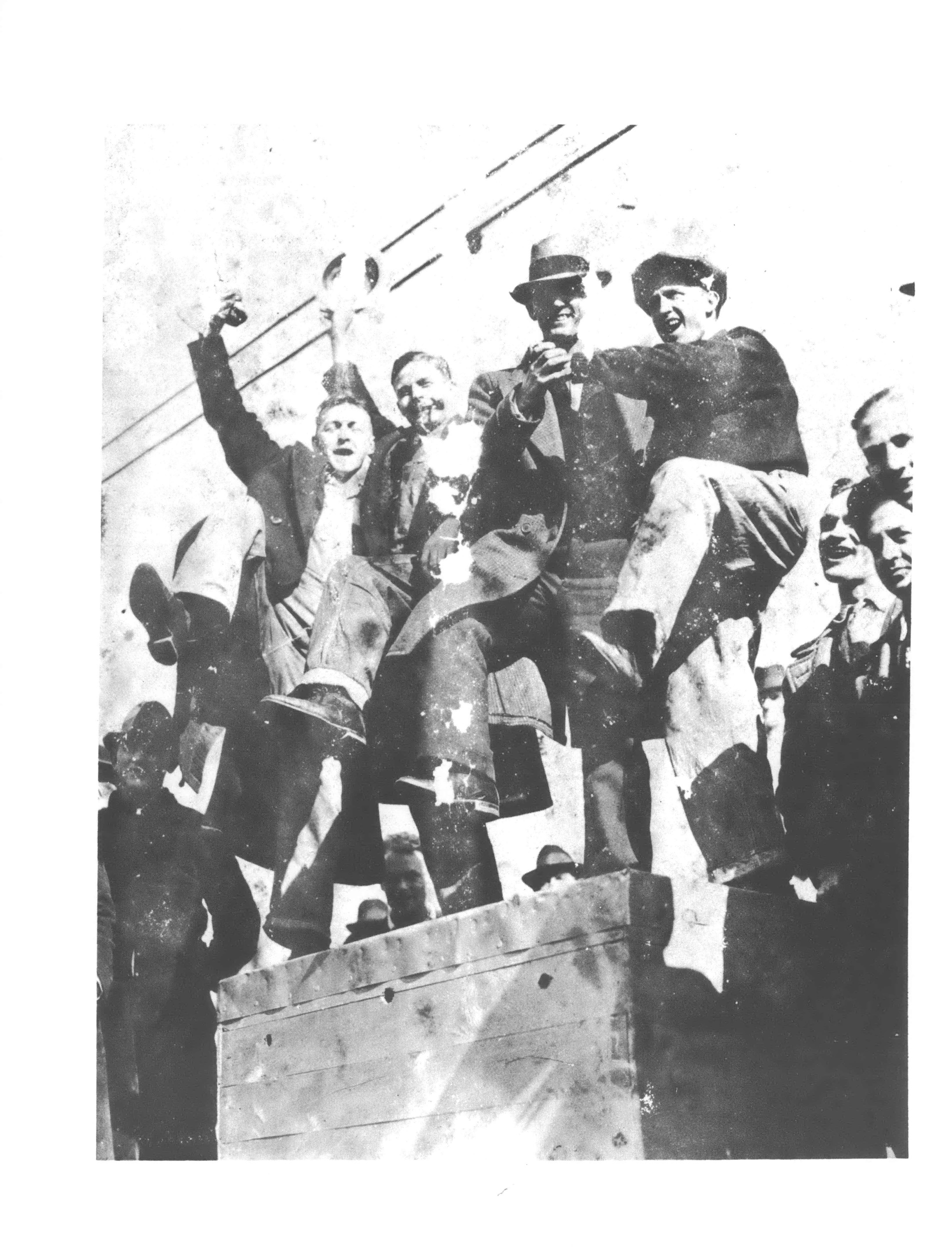

Mr. Smith: I’m the guy that went and got permission to close the line down. The foreman, he walked up to the line and said, “Smith, if you push that button you’re gonna lose your seniority.” I said “To hell with it.” I pushed the button, and that stopped the line, the first line that was stopped, General Motors Strike, 1936-37.

That was in the cushion department. I was steward in the cushion department. The issue was over the union button. My foreman told two of the boys that was wearing buttons, Fred Tyson and Fred Morgan, that if they didn’t pull the buttons off they would have to go to the office and be fired. They came to me and asked me what to do about it. I told them I don’t know, I will be back in a minute. So, I went over on the main line to see the president, Charlie Gillman. I said, “Charlie, they are after two of my boys over in the cushion department about the buttons. What do you want me to tell them?” He said, “You tell them, by god, to wear them.” I went back over there, and that’s when I reached up to push the button, and he said you’re gonna lose your seniority. I told him it wasn’t worth a damn nohow, so I pushed the button. So after I pushed the button, my foreman said, “You’re going to the office.’’ And by that time all the people that I was steward over, just ganged around me and said he’s not going anyplace.

After I got permission from Mr. Gillman to go back to tell the guys to wear the buttons, I went by and told Mr. Rawls, the vice-president of the local what the score was, and he jumped over out of the paint department into the cushion department and jumped up on the table—he had great big old feet, and he weighed about 200 pounds. He stamped his feet about four times, and waved his hands like that and everything in there went just like you could hear a pin drop. Every line stopped; every man except one, Zinc, he kept working. Somebody slapped him up the side of the head with a metal finisher. He stopped working then.

We stayed in the plant that night, all night, and we left the next morning about 9 or 10 o’clock. Our wives had formed an auxiliary and brought breakfast to us. We formed two lines for their protection—they was going to keep them out—so we just went down and made a walkway for them to bring food in.

How long had you been working in the plant then?

Mr. Smith: I built the first cushion that was ever built over there. I transferred from Norwood, Ohio, to the Atlanta plant. That was in ’36; I had been working for General Motors ten years then. I went to work for them in 1926 in Norwood.

We all spent the night in there. Somebody slipped in and raised the skylight on us trying to freeze us out. But we pulled all the seat covers, cotton bats, and everything else. We made beds. (Laughing.) I guess we did $10,000 worth of damage to the materials.

Mr. Cowan: I doubt that.

How many people were inside the plant?

Mr. Smith: Oh, I don’t know. There was a full shift in there, just about it. There wasn’t many people went home.

Mr. Pike: I’d say 95 percent stayed in.

Mr. Cowan: We sent some out to bring in tubs of coffee.

When those people went out to bring food back in, did they have any trouble getting back into the plant?

Mr. Smith: No, we formed a line.

Mr. Cowan: We made it easy. We told the guards that if they didn’t open the door, we were going to open it for them, one way or the other. . .so they backed out, and let them open it.

Mr. Starling: One incident about the food that I remember, they said they couldn’t bring food into the plant. Fred Pieper was outside, you know. He had been appointed by the president of the international union, Homer Martin, to supervise this area. Fred told them, “Well, if we can’t bring the food in, we will mail it in. You can’t stop the mails.” So then, they finally let them bring it in.

I think the point that really should be made is why did we leave the plant. Now most of the sitdown strikers stayed in the plant. But the committee met with management and Fisher Body—that is where the strike started—and they agreed that if we would vacate the plant that they would not attempt to operate the plant or move any of the plant equipment out until the strike was finally settled. And under those circumstances, we come on the outside the next morning and formed a picket line?

And how long did the strike last after that? That was the beginning of a long strike, wasn’t it?

Mr. Pike: Three months and three days.

Mr. Waldrop: Ninety-seven days.

And the strike was settled nationally after the Flint sit-down strike?

Mr. Starling: Yeah, in organizational techniques, they had led us to believe that all the plants were organized, well organized, better organizednthan ours, and we were holding up the organization. We found out that after we struck this plant that we were the only plant that could strike. They were not able to shut any of the rest of them down.

You were the very first plant to shut down, is that right?

Mr. Starling: Yes. Later, and I don’t remember in what order, but finally the Norwood plant went down, then the St. Louis plant went down, then the plant in Kansas City went down. So actually what happened in that strike that started in ’36, all the plants. . .the only plants that went down in ’36 were plants outside of Michigan. None of the Michigan plants went down until January of ’37. That was when they had the sit-down strike in Flint. Turned out that southern plants went down before any of the plants in the north were able to shut down. There was negotiations then. Course I wasn’t, none of us here participated in the national negotiations. National negotiations were handled principally by John L. Lewis, and the Vice President of the UAW, Mortimer. We were just looking at the original contract earlier and of course it was signed by William Knudsen, the president of General Motors. He had said less than a month before the contract was signed that he would never sign a union contract. But he did. I believe the contract was finally signed in February, 1937.

Did you have any trouble in the plant after you went back to work?

Mr. Smith: Oh no. They wasn't looking for no more. They had had all they wanted.

Mr. Starling: After we went back, they made most of our stewards foremen. I assume they thought if they could make our stewards foremen, they could control the union. But they did attempt to organize a company union at Fisher Body, known as Fisher Body Employees Association which they set up, but it never did materialize into anything substantial. For instance, the plant manager, a guy by the name of Gleason, headed the union. He attended all the meetings and was the union advisor, so you can imagine what kind of a set up it was—strictly a company union set up.

Mr. Smith: Shank, in the maintenance department, was the head of it.

Mr. Pike: They also fired him [Shank] after we went back to work.

Mr. Smith: There was too many catcalls whenever he would come in to work. Why, it sounded like a fox chase from the time he would come in the front door until he would get to the pen they built for him back there in the back.

Mr. Waldrop: You asked if we had any trouble in the plant after we went back. I suspect about the biggest trouble was unexplainable accidents. A lot of times heavy hammers would fall off the top of the job on somebody’s poor head.

Would that be somebody who hadn’t gone out during the strike?

Mr. Waldrop: That’d be right. That would be somebody we were having trouble with.

Mr. Starling: Oh, we had some trouble after we went back with some of them that didn’t want to join the union, but we were successful in convincing them that they should join the union, so we had a very strong union after we went back. The only thing that made the strike successful was the fact that people who were not members of the union supported it, and after we went back, those people joined the union, paid their dues and all. The few exceptions, why their jobs were not too desirable for them in the plant under those circumstances, so most of them either joined the union or quit and left.

Mr. Smith: Tom King. He was a company union man, one of the officials of the company union. They sent him to Detroit. But after we went down and talked to him at his house that night and convinced him that he was on the wrong side of the fence, he brought the majority of the company union boys into the union.

Mr. Waldrop: Yeah, when he got converted, well, it didn’t take long to convert the rest of them.

Mr. Starling: Yeah, Tom King turned out to be a very strong union man.

Mr. Waldrop, what department were you in? What were you doing at the time the strike started?

Mr. Waldrop: I was in the trim department. I would say in that department there were at least 250 men. I was putting windhose on the panel. That is that little roll that goes around the door. It was a rubber tube covered with fabric. I was working on the tables—I wasn’t directly on the line. There was me and six girls working together. So, whenever I heard that the rest of them across the cushion room had set down, I went down the line telling them that the boys had set down, and for them to get out of their jobs and quit. So, as fast as I could go around and tell the boys what was happening they began to pile out and it wasn’t long until every line in the plant was shut down.

Did the women stay in the plant or did they go out?

Mr. Smith: No, we let them go out, and they brought back in food.

Do any of you know how big the plant was at the time the strike began?

Mr. Starling: The total employment in the plant, now this included the management, the office and all, was right around 1800.

Mr. Pike: About 1300 actual production workers.

Mr. Starling: I was in the paint department. The bodies were started in what we called a set up, the set up in the body shop. The frames were built there and they were actually built with wood in the body shop, then they were put on the line and the metal was put on them, and the finishing, you know. You see, the difference between the body today and then, all the metal now is stamped out; then it was put on in pieces and welded by hand.

How about you, Mr. Pike, what department were you in?

Mr. Pike: Body shop, where it started off. I was a paneler. I was nailing a metal panel over the wood frame above the end of the roof and on each side of the windshield opening.

When the strike started, everybody just sat down and walked around and played checkers and so forth. Nobody went out at all during the day. Later on in the afternoon, we got together and agreed who would go out and so forth. But nobody—nobody, period—went out during the day time until this decision was made to let certain persons go.

Now during that morning when we sat down, some fifteen or twenty minutes prior to time for the regular after-lunch whistle to blow—I don’t know why they picked this one superintendent. See you’ll have superintendents of trim, superintendents of paints, superintendents of body—this guy was superintendent of the body shop—he went all over the plant telling the men, “We are going to start the line at twelve o’clock. Those who want their jobs had better go to work. Those that don’t go to work are going out, they are fired.” Charlie Gillman, our president, was five foot behind him telling them, “He’s a-lying to you, nobody will get fired; nobody will get run out, everybody keep their seat.” So twelve o’clock, they blew the whistle and started the line and run it about ten seconds and stopped it. Nobody worked.

What department were you in, Mr. Cowan; what did you do?

Mr. Cowan: Trim department. I was in final assembly for about two years, put in glass and c.v.’s you know that little bitty glass that you roll out to let the air come in—I was putting them in, then I got transferred to headliner. That’s upholstering overhead, you know.

I was working all the time for the union. I tell you when we got really active in that union was when President Roosevelt came on the radio one night and said you laboring people get busy and get organized and pay a dollar a month and join the union, because these companies are paying more than that to get together just to keep y’all from having one. So we got strung out in there, and this gentleman Fred Pieper brought us four or five buttons that he had in his pocket, and we put them on. First thing you know, here comes the foreman or superintendent behind us wanting to see what it was, and then they would take off to the office. Well, the foreman came back in a little while and said, “You’ll have ten minutes to pull them off or get fired.” Now this happened in our department. We didn’t have but about eight or ten buttons in there at most. We all got our heads together and said let’s pull them off until lunch time, and then at lunch time, we all went out and several of us came back with pocketsful. Everybody came running to us wanting buttons. They went down the line like a fire was after them or something. So we put them all on then after lunch. They didn’t run us out then; we had too big a thing going, I reckon. And the men were getting the buttons, just grabbing them and running. Here put this button on! Just tearing out down through there! A lot of men who hadn’t even joined the union put them buttons on.

Mr. Smith: They all was give out from working overtime and just being—I mean we was horse-whipped over there. They would tell you if you can't get it, there is a barefooted s.o.b. out front that wants your job.

Mr. Cowan: Yeah, they wouldn’t mind telling you there’s a one-armed man or a one-legged man out there wanting your job.

And so you had to work overtime if you wanted to keep the job? How much were you getting paid per hour, do you remember?

Mr. Cowan: Thirty-five cents an hour.

Mr. Waldrop: There was no overtime provisions whatsoever at that time. The only promise you got out of overtime was that if you didn’t work it, you was fired.

Mr. Cowan: Before we even got a contract—excuse me, y’all correct me if I’m wrong—after we had started organizing, they raised it from 35 cents to 60 cents an hour, trying to get us to break it up then, you know. And we all got our heads together and said, well, if it’s that much just trying to organize, we’re going to get more than that.

How much did you get per hour after the contract was signed?

Mr. Smith: It was on piece work then; but we were guaranteed 35 cents an hour after that.

Mr. Waldrop: You had a guaranteed wage of what you made at piece work plus overtime, and you didn’t get much over your standard salary even at piece work.

Mr. Starling: After we were organized they raised the day rate, that is what you were paid when you didn’t make out on piece work, they raised it from 35 to 65 cents an hour.

The most effective thing, I think, we were able to use was the statement that Roosevelt made. I don’t remember now when it was or under what circumstances, but the statement that we always quoted in the leaflets that we put out said, “If I was a factory worker, I would join the union.” We used that very effectively.

Mr. Smith: That is some contrast to what we’ve got now!

Mr. Pike: Some of the unpleasant conditions at the plant before this sit-down: we changed models each year and each year we would be off a week to three weeks to three months even, and when they would first start taking someone in the body shop back in—maybe they would take three today, the next day they might not take any more, the next day they would take thirty or forty. There were about 225 employees in the body shop alone. All body shop employees had to come right out in front of the plant and they had rails around the platform where you would enter. We called it setting on the rail, you see. You would have to come out there and set on that rail from 7 o’clock in the morning all day long, and if they didn’t call you, then you would go back the next day. Maybe you would go for 30 to 60 days like that each working day in the week. You would never know whether you were going to get to go in the plant, and a lot of them never did get back in the plant when the model change went down. And those was the conditions we had to stay employed.

And was that condition done away with under the new contract that was signed in 1937?

Mr. Pike: Absolutely. They notified us by mail when to come in.

Mr. Smith: Now another thing was if we had a breakdown, then they would knock you off. If it was ten o’clock in the morning they would knock you off, and you would have to go out and sit on this rail, and wait until they got it fixed, and if they got it fixed, they would call you. If you wasn’t there, you would be fired. Well, if they called, and it was four o’clock you had to go in. Didn’t get any pay for the time you was sitting out there.

Mr. Starling: Yeah, then you would work overtime to make it up. I think, of course you can get a copy of the original agreement and look it over, it is just a one-page thing. Now actually in the signed agreement we didn’t get anything except recognition for our members only. We were not permitted to bargain for anyone but our members. But, I think, following the settlement of the strike we had some of the most effective bargaining in the plant that I think we ever had, because of the way we handled it. The company wanted to bargain with the people individually, so they adopted what they called an open door policy. The manager’s door was always open. Any employee could come in and discuss any problems he had with them at any time. And what we did, in the departments, one employee had a problem, we all had a problem, and so we would all go down to the office to discuss our problem with them. Now that shut the whole plant down. And so we really got some effective collective bargaining because they had to settle the department’s problem before they could get the plant to operate, and we used that very effectively after we signed the first agreement.

What gave you the idea to stay in the plant and sit down rather than going out and picketing?

Mr. Starling: We knew that we didn’t have enough members. If we just took our members out of the plant they wouldn’t miss us, but we knew that if we could get the people to stay in the plant that they couldn’t operate it. Fortunately, although the people were not members of the union—not very many of them—they all stayed with us. Then that gave the people a boost to see that they could be effective if they stuck together, and then when they came outside they stuck together. Oh, we had some dissidents outside that tried to get petitions signed; they would go around and try to get employees to sign petitions to go back to work. The company was able to get some people to do that, some people in the bargaining unit, the production unit. But we kept pretty close check on them and the company didn’t get those petitions, we got them. We would catch them out with a petition and we would take the petition away from them, and tell them they better not show up around here any more, and they wouldn’t, they wouldn’t come back.

Mr. Pike: Then we would go have a talk with those people whose name was on that petition, we’d explain to them that that was totally ineffective.

Was the company behind those petitions?

Mr. Waldrop: Sure they were, yeah. Naturally it was a company union.

Mr. Starling: Some of them were foremen that was taking the petitions around.

Later on, before I left the plant in ’41 to go on the Executive Board, we got strong enough that if you had a person in your department that didn’t pay his dues, none of the other employees would cooperate with him, and working on a moving line you have got to have the cooperation of employees or you can’t do your job. We had to collect our dues. We had a steward in each department that collected the dues, and sometimes there would be a person who had joined the union, but didn’t want to pay his dues. I know there was one in my department that we had to do that to almost every month, but we would make it so hard on him he couldn’t do his job. The superintendent would come along then and he would just eat that foreman out because he wasn’t getting the job done. That foreman would go to this individual and say, “Now listen, I know why you can’t get your job done, because you haven’t paid your union dues. Now, I’m not going to lose my job because you haven’t paid your dues. If you don’t pay your dues, I am going to fire you. If I don’t fire you, I’m going to get fired myself.” And he would pay his union dues.

Mr. Waldrop: That was along about the time that I said there was too many unexplainable accidents happening to those guys that didn’t pay their dues.

Mr. Starling: As good a friend I guess as I had in the plant afterwards was a fellow that didn’t like to pay his dues. I was riding him one day, and he invited me outside after the line went down, so, we went outside, started fighting out in front of the plant there and got over on company property and the guards came over and made us leave. Then we went down across the railroad track where the parking lot is now, and we went down there and finished it off. He paid his dues up, and he was as good a friend as I guess I had in that union afterward. I mean a real friend; I don’t mean that he was just a fair weather friend. He never got behind in his dues again. He said that he realized that if he wanted to work in the plant he would have to pay his dues, and he said later after we got some more benefits that I did him a favor. He appreciated it.

The company hired a lot of policemen and put them in the plant during the strike. And they tried to operate their company union too during the strike but they were not successful in having any meetings at all. They tried to bring the president of the company union in the plant there one day and we wouldn’t let them bring him in. Sturdevant was chief of police here then, and he tried to take him into the plant, but he wasn’t able to get him in.

Mr. Pike: In other words, the chief got fired himself. Chief of Police of the City of Atlanta. He had no jurisdiction out here, it was in the county at that time. But he started in the plant with two fifths of whiskey. See, his son was one of the policemen inside the plant hired by the company. He got his whiskey busted out in front of the plant and turned back. The county police made a case against him. The city of Atlanta fired him shortly after that.

Mr. Smith: He told the county police when they came to us, “You don’t know who I am do you?” and they said, “Yeh, we know who you are, you are Chief of Police of the City of Atlanta, and we are just little old county police but you are under arrest.”

Mr. Waldrop: You made mention a minute ago of who worked in the plant while we were out. Well, now, they had received quite a quantity of materials, motors especially, before we came out, and after a certain period of time they had the foreman loading these motors back in to . . . they had 26 cars on the siding, and they had the foremen loading those motors back in the cars and they was going to send them back north, but when they got them loaded, and they called the railroad to come and pull those cars out, somehow or another, that phone call would wind up in the union office. By the time the engineer would get out here, we would have about a hundred men sitting over there on the railroad track and he would turn around and go back. They couldn’t get in there to pull the cars, and that happened daily for a couple of months.

Mr. Cowan: Yeh, when the train would pull up there some of the colored boys that was working there would lay right down across the track and wouldn’t move, and they would just come easing on up right close to them and stop and back out again.

Were people arrested during the time that you were picketing and out on strike?

Mr. Cowan: There was some arrested, but they never did get to jail with them. We had somebody there to get us out when they got down there; we never did go inside the jail.

You were all working almost full time during that three month period to keep the strike going? Did you maintain a picket line all the time?

Mr. Smith: Oh yeh, there wasn’t nobody laying down on the job.

Mr. Starling: Oh, yeh, we had a picket line all the time, 24 hours a day.

And nobody worked in the plant during that three months, they couldn’t get anybody to come in and do any work?

Mr. Cowan: Well, we had a few scabs. But it was hard to tell how many. They couldn’t stay long.

Mr. Waldrop: They couldn’t turn out any production.

Were you getting any kind of strike pay or any assistance during the time you were out?

Mr. Smith: I want to say this. I think this should be said, the womenfolk really stuck with us. They set up a soup kitchen and fed us, and we got a little help. John L. Lewis sent us a carload of coal, and we got a little help from other sources. Then finally we run out of money and didn’t have nothing, and there was an old man Haverty here that owned Haverty furniture store who loaned us money.

Mr. Cowan: He got our business after that.

Mr. Smith: I was on the fund committee collecting funds. I went to Augusta, Savannah, and we hit all the banks for different contributions. They wouldn’t give us any money; they would write us a check—me and Bob Geison on Chevrolet side went together. Ah, I wore out an automobile during that strike.

Mr. Waldrop: We did have a few good friends in Florida; all the truck drivers were really good about bringing up fruits and vegetables and stuff like that that went good in the soup kitchen. It was my job, there were three or four more, we knocked on places downtown, went from place to place, and asked for donations, especially in wholesale groceries. And our ladies, they manned the kitchen day and night from the time the strike started.

Mr. Cowan: The farmers’ market, the stuff that they couldn’t sell, they would give it to us by the bushel, and we would come right back out here and eat it. And a lot of local merchants, grocerymen and all, gave us food. We got a lot of support.

Mr. Starling: I think there is another thing we should mention; we did have good cooperation from our creditors. We all owed money. We set up a committee to go around and talk to people you know on behalf of the workers that owed money for different things, automobiles and different things, and they deferred payment in most cases until after the strike was over. We had good cooperation there, and with water and light bills and things like that. And we had good cooperation from the railroad. Now, they’re the ones that would notify the local union whenever they had an order to take anything in and out so we could be prepared to stop them. We run that strike, though, for over three months, and the total money that was spent on that strike though was between seventeen and eighteen thousand dollars for three months for 1300 people. We didn’t have much. We always had black-eyed peas and cornbread, and we ate a lot of it.

When we interviewed Mr. and Mrs. Charlie Gillman, the subject matter ranged far beyond the particulars of the strike in 1936. Mr. Gillman worked for the C.l.O. as an organizer from 1940 until his retirement in 1967, and he has a fairly developed perspective on the labor movement and the working class in the South. Likewise, Mrs. Gillman’s views are valuable since the lot of a trade-unionist and his family has been less then perfect in this region of open shops and ‘‘right to work ’

While to the average reader history is the exposition of factual matter, to folks like the Gillmans, it is the substance of their lives. Their understanding of events is drawn more from their experience than abstract learning, and that experience has been one of hardship relieved only by collective action. Their views are thus critical; but a critical spirit motivated not by malice so much as a deep affection for their class, a spirit explained by Mrs. Gillman in the word Solidarity.

While space prohibits our presenting the full range of the Gillman’s comments on the working class, present and past, we are publishing this sample that we think is representative of their views, feelings, and outlook.

Charlie Gillman: There’s one thing that’s different today among people, working people, than it was then. Back in those days after we formed the union, anything that happened in the plant that was an infringement on the rights of any worker, we represented them, although some of them did not belong to the union. If it affected one person then it was a problem for the whole shop, for everybody in that plant. Whereas today, practically anybody that works for a living, even members of the union, don’t want anyone to bother them. If something is done that affects Joe over here, so long as it doesn’t affect Jim here, well, that is all right. That feeling has gone through the whole community, not just the labor unions. That feeling is prevalent in nine out of ten people who work for a living that you talk to. They don’t want to upset the apple cart today—just don’t care if there is a depression over here for this group of people, or if they close the plant down over here and go out of business, and start up somewhere else. Don’t bother me because I’m doing all right today.

Do you suppose it is prosperity that brings out that attitude?

Mr. Gillman: Yeh, there is no doubt about it, I think it is going to take a depression—well, we have been in a depression for some time—but it is going to take a real depression to get people to realize that their neighbors are human beings the same as they are. And that is an awful price to pay. The only salvation of the thing is to work together instead of being so darn selfish, and being concerned with themselves always.

As I say, people are getting too complacent. There is a good danger that the unions may weaken; they’ll get weak too if they don’t watch themselves. I think this country is in for a real fall one of these days, because the credit now in force is the greatest it has ever been by far in this country before. And if some kind of recession starts—it got started here a few months ago, when the unemployment figures jumped way up, and it is only 5 percent now. If the unemployment gets serious, this country is going to be in some position.

Did you notice much difference in how strong a local was as to how hard it was for them to get started, like if they had to strike to get started, were they generally stronger than one that didn’t?

Mr. Gillman: It’s the only thing that ever builds a union. I’ve always said a union is absolutely no good without a strike, because the people don’t get together. A strike draws them together, they suffer a little bit, and it teaches them that they have to work together and try to help each other. There are very few good strong unions that haven’t been through a few strikes before. If the union is not strong enough to strike, they are not going to have much of a contract either. I don’t care who they are. Preachers, doctors, or whatnot. The whole rubber industry was tough to organize, about like the auto industry. They had to fight to build their union; the contract wasn’t handed to them at all.

There’s been a lot of good unions in this part of the country, and it’s actually a matter of leadership. A lot of people these days who belong to a union and get elected to office, all they want out of that office is the recognition. They don’t want to do any work while they are in there. They just want to be called the Secretary or the President or something. You just simply don’t have the leadership that you used to have, and you haven’t got the people who are interested in developing the benefits that the people need anymore. I think that, more than anything else, worries me about the working people, because when times get tough they are the ones who are going to suffer. There is no if, and, and but’s about it. They are the ones who will be thrown out of their jobs, and they’re gonna be on short time. But when times are good, you just simply can’t make them understand that, and you can’t make them talk to you about it. They say, oh, it can’t happen to me. But I’ve seen it happen.

What do you suppose happened in the union that caused them to allow the grievances to pile up the way they have?

Mr. Gillman: It’s because they have such a contract now. The contract is so bulky it takes them months to get through the thing. Back then we would go one place and that was it. If it wasn’t settled there we would appeal it to the committee right away in Detroit, and we would go up there, and sit down and settle it with the top men in the company. Now, you’ve got to go through this procedure and that procedure, and if that doesn’t work you have got to have somebody come down and meet with them, and if that doesn’t work you go somewhere else. The bargaining relations are not as good as they used to be because the union has allowed the company to get by with so many little things because people are making pretty good money and they didn’t want to be bothered with all these little problems themselves.

What kind of future do you see for the labor movement in the South.

Mr. Gillman: Oh, I think we are going to organize; it’s going to have to come. There is one thing that is helping more than anything else, and that is that organized industry is moving into the South. Practically all the corporations that have moved their plants here or built plants here are organized up the country. Our membership is growing pretty good. We’ve got, I suppose, better than 200,000 members in Georgia now. And they estimate the number in Florida at 350,000 down there. So there are a lot of people moving down here that are from organized plants. Alabama has a good organization.

It’s growing, but it is awfully slow. The main thing that has kept the unions out of the South . . . well, there are two things. One is that the people didn’t know anything about unions at all, and the other is the textile plants. Textiles, whether you think so or not, established the living conditions in practically all small communities and areas in the South. Up until recently they owned the houses that the people rented from them, and they had restrictions: you couldn’t do this, or that or the other in the community, and the supervision in the textile mill were actual dictators of the people who worked, you know, “the hands.” They could fire you with no reason, just kick you right out, and if your wife worked there, they could kick her out, too. People don’t believe it, you can tell them about these things, but they look at you like you’ve got jaundice or something, but it is true, because I was in those places, and I know, and we tried to work where those people today are scared to death to talk to union people.

Mrs. Gillman: A lot of that is because in these little small towns, particularly in South Georgia, they are church-oriented towns, and the preachers are definitely against unions.

Mr. Gillman: They are on the payroll of the company.

Mrs. Gillman: And they preach against it; they visit their people and they talk against it, and to many people in small towns what the preacher says is the thing that goes. Now you can take a city like Atlanta, Decatur, and parts of DeKalb County that are close to Atlanta and Decatur, that doesn’t hold true at all, because the people are more educated, and their lifestyle is entirely different to that in small towns. I think a lot of it you can attribute directly to preachers and I don’t say that with any disrespect to them or anything like that, but having been through so many years of this, you are a fool not to recognize just exactly what it is they are doing.

Mr. Gillman: It was a great life. Lot of hard work, discouragement, and a lot of pleasure. And I think that the satisfaction that you get out of what has been accomplished by the union is worth everything you put into it. It’s just criminal almost that the young fellows who go to work now have no appreciation of what a union has done to their job for them, because their jobs that they are on now wasn’t always that kind of a job. It was built to where they had the benefits that other people worked for, which is the way it ought to be, but they ought to know about it anyhow. Well, it’s a great life.

* The interview with the Gillmans was conducted in October, 1973, at their home, by Neill Herring and Sue Thrasher.

**The interview with W.A. Cowan, Harvey Pike, Claude Smith, Tom Starling, and Mark Waldrop was conducted by Sue Thrasher at the union hall of UAW Local 34 in September, 1973, and was arranged through the courtesy of W.A. Cowan, current president of the Retirees’ Local.

Tags

Neill Herring

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)