This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Editor’s note: The century-long denial of voting rights in Edgefield, South Carolina, chronicled here by Laughlin McDonald, exemplifies the importance of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the battle now shaping up in Congress over its extension.

In 1880, B.R. “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman was elected chairman of the Democratic Party of his native Edgefield County, South Carolina. In the years that followed, as a local politician, governor and United States senator, Tillman earned the reputation of being a savage racist and the single person most responsible for the total exclusion of blacks from state elective politics after Reconstruction. Nearly 100 years later, on a cool spring evening, Thomas C. McCain, a black man, was elected to Tillman’s line of succession as the newest chairman of the county Democratic Party.

McCain’s election is part of the dramatic racial change that has swept the South since the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. But racial change in Edgefield, a rural county lying next to the Savannah River 15 miles north of Aiken, has often been more cosmetic than substantive. In spite of the fact that blacks hold local party positions, no black in a century has ever been elected to the county government, nor has a black been elected to any countywide office running against a white candidate. Ruling whites in Edgefield aim to keep it that way.

Voting rights have always been seen as key to racial equality — political, social and economic. George Tillman, Ben’s older brother, stated the proposition succinctly in 1868: “Once you grant a Negro political privileges a . you instantly advance his social status.” If given the right to vote, said Tillman, blacks would vie with whites for the honors of state and support only those who treated “the nigger race as social and political equals.”

George Tillman’s worst fears were to be realized during Reconstruction. Edgefield’s majority black population voted in their own town and county governments. By the mid-1870s, the county senator, county representatives, county commissioner, the coroner, sheriff, probate judge, school commissioner and clerk of court were all blacks. Blacks served on the school board, as magistrates, solicitors, wardens, and at every level of city and county government. Blacks in Edgefield were never better represented, before or since, nor had more opportunities for advancement, than during the period of Reconstruction government.

Whites never acquiesced to black rule. After general enfranchisement in 1867, local Democratic and agricultural societies sprang up; among other goals, they used social and economic coercion to deter blacks and white Republicans from voting. The Democrats failed in these early attempts to regain dominance, and turned increasingly to fraud and violence as a means of restoring political control. Rifle and sabre clubs were formed in virtually every township, and operated literally as a terrorist wing of the Democratic Party.

Ben Tillman was a charter member of one such club, the Sweetwater Sabre Club, organized in 1873. He became captain three years later, and was in command when two of his men executed Simon Coker, a black state senator from nearby Barnwell. According to Tillman’s biographer, Coker had been seized for making an “incendiary speech.” As the bound senator kneeled in prayer, he was shot in the head by one of the Sweetwater clubsmen, while another put a second bullet in the prostrate corpse to make certain he was not “playing possum.”

Violence reached an apogee in Edgefield County in July, 1876, at the notorious massacre in the town of Hamburg. Ben Tillman, one of the participants, conceded that it “had been the settled purpose of the leading white men of Edgefield to provoke a riot and teach the Negroes a lesson — and if one did not offer, we were to make one.” Rampaging whites attacked the town and killed a number of blacks. When none were tried or convicted for the murders, it was taken as a sign that Republican control had been broken, and that Reconstruction was coming to an end.

The results of the next election in 1876 were determined by the “Edgefield Plan” for redemption, authored by George Tillman and General Martin Witherspoon Gary, the fierce, unreconstructed “Bald Eagle of the Confederacy.” The watch word adopted for the campaign was “Fight the Devil with Fire.” Every Democrat, the standing rules provided, “must feel honor-bound to control the vote of at least one Negro, by intimidation, purchase, keeping him away or as each individual may determine, how he may best accomplish it.” As for violence, never merely threaten a man: “If he deserves to be threatened, the necessities of the times require that he should die.” Ben Tillman wrote later that “Gary and George Tillman had to my personal knowledge agreed on the policy of terrorizing the Negroes at the first opportunity.”

On election day, Gary and several hundred armed men seized the two polling places in Edgefield — the Masonic Hall and the Courthouse — and refused to allow blacks in to vote. Open race warfare, together with Gary’s doctrine of voting “early and often,” was enough to ensure a Democratic majority. The following year, the Edgefield Plan was essentially condoned by the Compromise of 1877, ending Reconstruction and withdrawing federal troops from the South. Control of Edgefield and South Carolina as a whole was left to men like Ben Tillman, who had vowed never again to see whites subjected to the humiliation of black rule.

The redeemers set about at once to institutionalize white supremacy. On the political front, the legislature passed in 1878 a law eliminating precincts in strong Republican areas and requiring voters to travel great distances to cast a ballot. Then in 1882, a complicated balloting procedure, amounting to a literacy test, was introduced; and another law required eligible voters to be registered by June, 1882. Those who failed to register were barred from registration thereafter, and the only additional registration was for those who became eligible after June, 1882. Local officials had full discretion in implementing the registration requirements, and aggrieved persons had to appeal within five days and institute suit within 15 days. The laws were an invitation to fraud, and were used for the sole purpose of disfranchising 90 Black candidate campaigning for election in the South during the Reconstruction era. blacks.

Tillman was elected governor in 1890 on a platform of Negrophobia and agrarian discontent. Although there were still a few blacks in the legislature, in his inaugural speech Tillman could safely say, “Whites have effective control of the state government,” and, he declared, “we intend at any and all hazards to retain it.” In his second term as governor, the redeemed state legislature abolished elected local governments entirely to put it beyond all possibility that blacks, even in places where they were an overwhelming majority, could have any say about who their representatives would be. County and township commissioners were henceforth to be appointed by the governor, upon the recommendation of the local senator and representatives. All powers to tax, borrow money, appoint local boards or exercise eminent domain were reserved for the state legislature.

Ruling whites, however, still felt the need for more systematic means to take the actual ballot out of the hands of blacks, and to replace the despised Reconstruction Constitution of 1868, known as the “Radical Rag.” Tillman took the lead in calling for a constitutional convention to accomplish both these purposes.

The convention was held in 1895. Tillman, by then a United States senator, was made chairman of the Committee on the Franchise. Under his leadership, the basic suffrage qualifications enacted were residence in the state for two years, in the county for one, and in the election district for six months; payment of a one-dollar poll tax six months before the day of the election; and registration. To register, the voter had to be able to read and write any section of the Constitution or prove that he owned or paid taxes on property in the state worth at least $300. For those who could not meet the literacy test by reading, there was an understanding test where the Constitution was read by a registration officer — who could be expected to be sympathetic to white and hostile to black illiterates. As D.D. Wallace, a contemporary historian, observed the year following the convention, “Such is South Carolina’s suffrage law, under which it is hoped to put Negro control of the State beyond possibility and still preserve the suffrage for the illiterate whites of the present generation.” So great was the fear of black participation in politics, however, that the year after the convention the all-white Democratic primary was adopted to exclude even those few blacks who were registered from voting in the only elections in the state which had any meaning.

Black disfranchisement, from the white point of view, was an incredible success story. In Edgefield, by 1900, not a single black remained on the county voter rolls, and none was to appear for nearly 50 years.

After years of protest, legal skirmishes and organized resistance within South Carolina’s black community, the Edgefield Plan received its first official blow in 1947, when federal judge Waties Waring of Charleston, in an opinion passionately denounced by whites throughout the state, ruled that the segregated Democratic primary was unconstitutional. Frank Jenkins, a bus driver for the Edgefield public schools, and several other local blacks decided it was time to test the decision upholding their right to register and vote. They went to the courthouse, but nobody could tell them who or where the voter registrar was. They came again and this time were dealt with more directly. “The man said,” recalls Mr. Jenkins wryly, ‘“If you don’t leave, I’ll kick your ass out of here.’” The group came back a third time — with a lawyer from Charleston — and were allowed to register.

In the face of such open hostility by courthouse officials and continued use of the discriminatory literacy test, black registration remained depressed in Edgefield until the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Immediately prior to the act, only 650 blacks were registered in the entire county — 17 percent of the eligible voter population. Nearly 100 percent of eligible whites, by contrast, were certified voters.

As one of the fruits of years of struggle by the Civil Rights Movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 formalized a major breakthrough in the legal rights of blacks in places such as Edgefield. Laws prohibiting discrimination in voting had been enacted by Congress before — in 1957, 1960 and 1964. These laws, however, depended mainly upon litigation for enforcement, which placed the advantages of time and inertia on the side of recalcitrant local officials. Moreover, there was nothing to keep a jurisdiction from changing its laws and enacting new discriminatory election procedures, even after the old ones had been struck down by the courts as unconstitutional.

To meet these problems, Congress adopted in 1965 an entirely new approach to voter legislation. It suspended literacy and similar “tests or devices” which had been used to exclude blacks from registering, and pursuant to Section Five of the law, placed supervision of new voting procedures in the hands of federal officials. Jurisdictions covered by Section Five — those with low registration or voter turn-out, and with a “test or device” in effect — were required to clear all changes in election laws with the U.S. attorney general or the federal courts in the District of Columbia before implementing the changes to make certain they did not affect a person’s right to vote on account of race or color. The entire states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Virginia and 40 counties in North Carolina were among the jurisdictions required to pre-clear their election law changes.

Southern resistance to the act was predictable. One of those who took the lead in denouncing it was Senator Strom Thurmond, born in Edgefield in 1902 and its former county attorney. The act trampled upon the rights of the sovereign states, he said, and made the South the whipping boy for the nation. Following Thurmond’s lead, the state of South Carolina filed a lawsuit to strike down the law, but the Supreme Court in 1966 found the Voting Rights Act to be wholly constitutional. As Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote, “Hopefully, millions of non-white Americans will now be able to participate for the first time on an equal basis in the government under which they live.”

The suspension of literary tests had a dramatic impact, and some Southern jurisdictions now register blacks at approximately the same rates as whites. But unfortunately, black registration has not meant equality of political participation. For one thing, many jurisdictions have ignored Section Five and made uncleared voting changes which blunted increased minority voter registration. Edgefield was one of those places.

In 1966, when it seemed likely that the county, because of its relatively small population, would lose a resident senator following reapportionment of the state legislature, and just as newly registered blacks were beginning to gain enough political clout to pressure their legislative delegation and the governor to appoint a black to county office, the method of selecting Edgefield’s government was changed to provide for home rule. A three-member council was established with full power to tax, make appointments and regulate county affairs. Although the council could have been elected from districts — which in the absence of a racial gerrymander would have created at least one black district — the decision was made to elect all council members at-large. Since whites in Edgefield in 1966 were a majority of registered voters, and a majority of persons eligible to be registered, the at-large plan ensured that whites could continue to control each local political office. And that is exactly what has happened.

Although the Voting Rights Act clearly required a federal review of this new voting procedure, state and local officials failed to submit the change. Two subsequent amendments to the 1966 law, one increasing the size of the council to five and establishing new residential districts for council members, and another enlarging the council’s power to make appointments, were submitted for pre-clearance. But the underlying change from appointed to elected at-large government has never been given the required federal approval, even after 15 years. By similarly manipulating voting procedures, whites in dozens of other Southern communities like Edgefield have blocked the election of blacks despite vastly increased black registration.

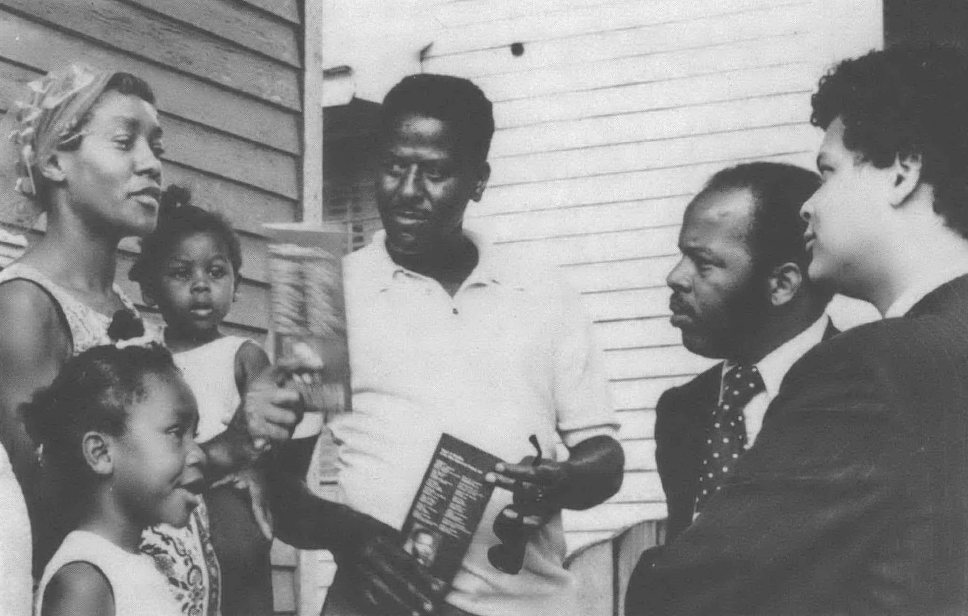

In 1974, Tom McCain, then an assistant professor of mathematics at Paine College in Augusta, became the first black since Reconstruction to run for Edgefield county government. McCain was well respected in the black community and was an advocate of racial justice. He founded Community Action for Full Citizenship of Edgefield County in the early 1970s, and began systematically to challenge local racial discrimination. He led the bitterly resisted fight to desegregate the schools, organized the county’s first black voter registration drive and successfully sued the Edgefield jury commissioners for excluding blacks from jury service — no blacks were allowed to serve on the grand jury and only a token number on trial juries.

As a result of his civil-rights activities, McCain has drawn the fire of local whites. Members of the school board have sued him twice. In the first case, they got an injunction against his further organizing, but when McCain was unable to get even a trial on the merits of the injunction, a federal judge, in an unprecedented move, stepped in and dissolved it. The second suit is pending, one in which the board seeks $240,000 in damages, claiming that McCain libeled them in a pamphlet which criticized the operation of public schools as discriminatory. Other local white officials display similar hostility toward McCain. Mary Ellen Painter, the head of the voter registration board, says he only wants “to cause trouble.” County Attorney Charles Coleman was quoted recently in a Georgia newspaper that if McCain “were a white man, I think he’d be Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.”

But Tom McCain is no racist and hardly a radical. His goal, he says, is merely for blacks to participate in the decisions that affect their lives. Levelheaded and hard-working — he is now finishing work on a Ph.D. in education administration at Ohio State University — McCain moves easily and unselfconsciously in the black community of Edgefield, urging people to register and become active in politics.

McCain’s decision to run for office was completely logical. “We’ve got so many problems in Edgefield,” he says, “we can’t begin to make progress unless we get some responsive people in decision-making positions. The whites know they can just about get along without us politically. That means we get only what they want to give us.”

County Attorney Coleman, however, scoffs at the notion that whites can’t, or don’t, adequately represent blacks. In fact he claims, “The blacks get as much or more service than the whites” from the present council. McCain disagrees, and notes that the black complaint is in any case more basic than provision of services. “There’s no question that we don’t get services like we should,” McCain says. “We never have. But even if we did, that would still miss the point. There was more to school desegregation than reading and writing, and there’s more to biracial politics than paved roads. There’s an inherent value in office-holding that goes far beyond picking up the garbage. A race of people who are excluded from public office will always be second class. I know it, and the people who keep Edgefield’s government all white know it.”

McCain lost the 1974 race for county council, and a second race two years later, because whites don’t vote for blacks in Edgefield. A visual examination of election returns reveals the severe racial polarization in local voting. In predominantly white districts, where voting patterns are clearest, black candidates always get virtually the same number of votes — few, or none at all. Bloc voting has been confirmed by Dr. John Suich, a scientist in Aiken, who has analyzed elections in Edgefield in which blacks have been candidates. The statistical correlation between the race of voter and candidate was “extraordinarily high,” in the range of 0.90 (on a scale of -1.00 to +1.00) for each election. “The correlations are not just statistically significant,” says Suich, “they are overwhelming.”

The election returns also show that if Edgefield were divided into five districts along its present residential district lines, two of the districts would have a majority of black registered voters. Candidates like McCain would stand a realistic chance of winning office in these districts, an opportunity currently denied them by the at-large system. Indeed, McCain won his position as chairman of the Democratic Party because the delegates to the county convention which chose him are elected from individual districts or precincts. Enough of the delegates were black to give him the margin of victory.

In 1974, McCain and two other blacks decided to do something about Edgefield’s elections and filed a federal lawsuit charging that at-large voting unconstitutionally diluted their voting strength. While the lawsuit was pending, the county council adopted an ordinance in 1976 implementing statewide home rule, and providing for elections at-large. The ordinance was a change in voting but was not pre-cleared under Section Five of the Voting Rights Act. As a result, the elections of 1976 and 1978 were held in violation of the act. A belated submission was made and in February, 1979, the attorney general objected to the use of at-large elections, noting that if a new election system was adopted “that more accurately reflects minority voting strength, such as single-member districts,” the objection would be reconsidered. A single-member plan was in fact prepared and approved by the council, but was never submitted under Section Five because the council later took the position that the attorney general’s objection was not binding.

When it appeared that the administrative proceedings under Section Five had broken down in Edgefield, and that no new method of elections was being established to meet the attorney general’s objection, the trial judge entered an order last April in favor of McCain and the other plaintiffs. The court reached “the inevitable conclusion” that Edgefield’s at-large system was unconstitutional and “must be changed.” Some of the court’s findings were:

• “Until 1970, no black had ever served as a precinct election official, and since that year the number of blacks appointed to serve has been negligible.”

• “Blacks were historically excluded from jury service in Edgefield County.”

• “Blacks have been excluded from employment. ... It was only when trial was about to begin that the county suddenly began hiring blacks in any numbers. ... In addition, blacks are heavily concentrated at the lower wage levels.”

• “Blacks have been excluded by the County Council in appointments to county boards and commissions.”

• “There is bloc voting by the whites on a scale that this court has never before observed.. . . Whites absolutely refuse to vote for a black.”

Four days after the court’s opinion, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively overruled it by handing down City of Mobile v. Bolden, a decision which shocked even those civil-rights activists familiar with the conservative rulings of the Burger court. The case originated when a group of Mobile black plaintiffs brought a lawsuit in 1975 charging that the city’s at-large elections diluted their voting strength in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and the Voting Rights Act. The plaintiffs based their legal claim primarily upon a 1973 court of appeals decision, Zimmer v. McKeithen, which held that at-large voting can be shown to be unconstitutional through an accumulation of circumstantial evidence — such as by showing a history of racial discrimination in the city, a disproportionately low number of minorities elected to office, lack of responsiveness by elected officials to the needs of the black community, a disparate economic base, candidate slating, etc. — the same kinds of things relied upon by the judge in the Edgefield voting case.

According to the Supreme Court’s Mobile decision, such factors do not in themselves establish an unconstitutional denial of voting rights. The court, in a split ruling, said that plaintiffs in vote dilution cases must prove intentional discrimination; they acknowledged that the Constitution protects the right to register and vote without hindrance, but held that it does not protect the right to have the vote count! That right would only be violated if the voting system where consciously conceived and operated as a purposeful device to further racial discrimination.

The Mobile decision places an all but impossible burden upon those challenging racially discriminatory election procedures. Invidious intent can no longer be shown by past deeds, a history of discrimination and its effects; only those challenges will win, presumably, when elected officials are caught making overtly racial defenses of voting procedures. None but the naive - or, apparently, Supreme Court justices — can expect that to happen very often. Public officials, especially those who are sued and represented by counsel, rarely admit to racism. Mobile means that blacks in jurisdictions which use at-large voting — including most Southern cities, counties and school boards — will be denied any remedy for exclusion from office.

Following the Supreme Court’s decision, the district judge in the Edgefield case withdrew his earlier opinion and reopened the case to give the plaintiffs a chance to prove that local elections were adopted, or are being maintained, intentionally to exclude blacks. Tom McCain then amended his complaint asking the court to order Edgefield officials to comply with Section Five’s preclearance requirements, both in adopting at-large voting in 1966 and in implementing statewide home rule in 1976. Given the normal practice of the courts to avoid deciding constitutional questions whenever possible, McCain’s complaint may be judged solely on Edgefield’s violation of the procedural requirements of Section Five rather than on the constitutional question of its purposeful intent to dilute black voting strength.

There is one major catch. Beginning August 6, 1982, South Carolina and most the South will be in a position to escape being covered by Section Five. The Voting Rights Act’s requirement that jurisdictions clear proposed changes with the federal government is limited to 17 years from the time they used a “test or device” to restrict voters’ rights — namely from 1965, when such practices became illegal. If the Act’s provisions are not extended by 1982, South Carolina can apply to be released from federal monitoring and can then ratify retroactively, or re-enact in new form, such uncleared changes in voting procedures as those adopted in Edgefield in 1966 and 1976.

The only handle for challenging discriminatory changes would then be lawsuits based on constitutional issues — the handle that existed prior to 1965. Except now the Supreme Court’s Mobile decision, with its artificial standard of proof of purpose, may make it impossible for minorities to win constitutional lawsuits where local officials successfully cover their racial tracks. It is not an exaggeration to say that minorities stand perilously close today to where they were in 1877, when the nation, grown weary of the race issue, agreed to let local officials deal with voting rights as they saw fit.

Organizing inside the South and by national groups is now underway to get Congress to extend the length of time states like South Carolina must follow Section Five. Saying “It is the duty of this generation of black people to take not one step backward,” a coalition of groups in South Carolina recently announced plans to push for the act’s extension.

National civil-rights groups, including dozens coordinated by the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, also hope to amend the act to provide the legal foundation to overcome the Supreme Court’s Mobile decision. For example, Section Two, which some of the Supreme Court justices now interpret as only prohibiting purposeful discrimination, might be amended to read: “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any state or political subdivision which has the result of denying or abridging the right of any citizen of the United States on account of race or color. . . .”

These organizing and lobbying efforts are expected to meet with stiff resistance, particularly from Senator Strom Thurmond, now chairman of the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee. Thurmond claims that the act “singles out the South” for special treatment, and he wants to abolish it or make its extension apply “nationwide.” Of course, the Voting Rights Act already is nationwide: it was amended in 1970 and 1975 to make the ban on literacy tests permanent and nationwide, and to expand the number of jurisdictions covered by Section Five to include those with significant language minorities; it now applies in 24 states or parts of states, from Maine to Florida, from the East Coast to the West. But Thurmond apparently hopes that by threatening to expand the act to require all states and all jurisdictions to pre-clear all changes in voting procedures, he will destroy the act’s efficacy, or he will capture enough support to kill it altogether. If the Thurmond strategy prevails, it will push the movement for voting rights back more than a century.

Thurmond even insists that voting rights don’t need protecting. “There’s no discrimination of any kind that exists throughout South Carolina,” he said recently. That should come as a surprise to Tom McCain and other blacks in Thurmond’s hometown of Edgefield.

Tags

Laughlin McDonald

Laughlin McDonald was born and grew up in Winnsboro, South Carolina, not far from Edgefield. Director of the Southern Regional Office of the ACLU, he has represented blacks in Edgefield County in numerous civil rights lawsuits. (1981)