What the Experts Say

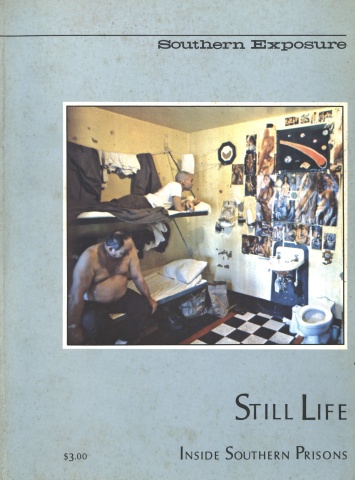

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

He began his career as a case worker for the Pennsylvania Prison Society. Nagel then served as the assistant superintendent of a New Jersey correctional institution from 1949 to 1960; director of the Pennsylvania Council on Crime and Delinquency from 1960 to 1964; and executive secretary of the Council for Human Services in the Pennsylvania governor’s office from 1964 to 1969.

A resident of Yardley, Pennsylvania, Mr. Nagel has served on numerous state and national councils on crime and corrections and has written many articles for professional journals. His book, The New Red Barn: A Critical Look at the Modern Prison System, was published by Walker in 1973.

The preceding essay is excerpted from an interview with Mr. Leeke conducted by free-lance journalist Mark Pinsky.

William Leeke has been working in corrections since 1956 as a teacher, warden, deputy and commissioner. He has served in his present position of Director of South Carolina’s Department of Corrections since 1968.

Currently president of the American Correctional Association, Mr. Leeke has also presided over the National Association of State Correctional Administrators and the Southern States Correctional Association.

Considered a liberal among Southern prison commissioners, Mr. Leeke is credited for his leadership in a nationwide study of court decisions concerning inmates’ rights and has pursued an active policy of equal employment in his agency.

Commissioner Leeke is responsible for 31 institutions, 1,600 employees and 7,700 inmates.

William Leeke

If I were in a position where I could sit and hypothesize about great societies, I would probably be in agreement with those who would say, “Let’s tear all the prisons down.” The reality of it is the country is not in a position to let us tear down prisons, even if we wanted to. I think we are always going to have a society that has a need to lock up dangerous people for simple social control, social order and protection of the public. But the idea that “people are sick; send them to prison and we can cure them” has no merit. It’s rather bizarre to think you can take a junkie and shove him into prison for two or three years, into a tremendously overcrowded area, and think you’re going to heal him. We can hardly even find doctors to work in large prisons because of salary schedules and because of the sheer threat to them just being in there.

There’s no question, I think, that we now lock up way too many people, but the rhetoric we hear is that we could tear down all the prisons and everything would be better. That is not going to happen in our society.

But I would look for every possible safe way not to resort totally to locking people up to carry out what we call our system of criminal justice. That would obviously involve ensuring that we had adequate probation and parole services and alternative programs that would prevent people from coming to prison. The thrust would then be, as far as institutional design, to learn from the mistakes that we have made in the past and to ensure, if nothing else, the safety of those people who have to be removed from society for a period of time. We would want to ensure that we do not let prison get so overcrowded that people have no identity whatsoever, where they can be raped or assaulted by their fellow man.

We want a safe place where people who have to be removed from society can retain as much dignity as they can, where they can remain in contact with their loved ones and where they can not be further damaged by having to be locked up. We’re all pretty much aware of the fact that, with the massive overcrowding that exists now, we can’t in all cases provide safety to the degree we would like to in our institutions. In many ways the federal district courts have been the salvation for state prison systems. While it’s not pleasant to be ordered by a federal court to do things, if the legislative branch of government fails to act, then the judicial branch must bring about change.

I hope the days of these big Bastilles are gone. When we have to build prisons, as a last alternative, we must make them smaller. The larger the number of people who reside in a prison, the larger the number of people working there, the more callous everyone becomes.

Of course, we hear objections to using any land anywhere to develop a new prison. It’s pretty ironic, though, that when people are yelling, “Lock everybody up, lock ’em all up, we've got to reduce crime,” and you try to find a site — no matter where — there’s going to be public opposition.

Me and My Necklace

By Danny Ray Thomas

South Carolina prison

I lay down on the locker

I have a necklace around my neck

And when I lie down

The necklace gently makes a clink

On the locker I’m laying on

I think to myself

Now the necklace

Didn’t sound right

I ease my head up

Slam my head back down again

And at the process I listen for the sound

Of my necklace when it hits the locker

And again, the necklace

Makes a gentle tap

Now I’m furious at myself

For not being able to make

The necklace sound louder when

It hits the locker

Rage in me at its height

I quickly raise my head

And quickly again, I slam my head

Down on the locker

And again, the necklace makes

Only a gentle thump

My God, I can’t make

A very small necklace

Make a loud thump

On the locker

I cannot hold the rage within me

I jump off the locker

Rip the necklace from my neck

I slam the necklace against the locker

Resulting in nothing

The most progressive thing we’ve gotten in South Carolina is a new program called “extended work release.” That’s where an individual who’s been in work release for two months and meets certain criteria can live in a home environment with a sponsor while he serves out the balance of his sentence. We require the participants in this program to pay $5 a day for their own supervision. This decompression chamber approach has given us a lot more flexibility in taking people from confinement and helping them to work their way back into the community. I think from sheer economics it’s a savings of a considerable amount of money in not having to construct a number of new beds for them, and at the same time requiring them to pay for a portion of their confinement. There’s no question that — especially where property crimes are concerned — restitution is also a very viable alternative. I think many average people obviously would rather have their property back, or replacement of their property, than see their insurance rates go up because of theft. They’d probably rather have their property back than get a pound of flesh by locking somebody up for a period of years. I’m a strong believer in restitution programs. But I don’t think they’re a total panacea. For property crimes it has great potential. But it will be some time, I think, before people are willing to accept a restitution system for crimes involving bodily injury or assaultive behavior. I’m really enthusiastic about the future of our criminal justice system. I see a period of a lot brighter and more intelligent people making a career of corrections — both men and women. I can understand how some of the new people coming into the prison system might think some of our institutions are still in the dark ages, but looking back on it, I can see a great deal of progress.

William Nagel

Prisons fail because of our multi-directional expectations of them. No cloistered institution can segregate, punish, deter, rehabilitate and reintegrate any individual or group of individuals. Yet these are the tasks demanded of prison by judges, legislators and segments of the public. To narrow these purposes, as many people are now proposing, will not make the prison more successful — only less hypocritical. Imagine, if you will, a prison with the singular purpose of “punishment.” What kind of staff would work in such a place? The very thought is frightening.

Prisons fail because the sentencing policies and practices which lead to imprisonment are unjust and stupid. Anyone who has visited prisons recognizes the racial injustices represented by the gross overrepresentation of blacks and other minorities. Anyone who has looked at the vast disparities in lengths of sentences senses the class injustices. Anyone who has observed that 90 percent of those in prisons are nonviolent first offenders recoils at the injustice and futility of that incarceration. Prisons fail because of their locations. The Olympic prison is the most current example. The Federal Bureau of Prisons has exchanged principle for expediency by capitalizing on the popularity of the Winter Olympics, the high rate of white unemployment in remote, rural northern New York state, and the power of a pork-barrel Congressman to build one more remote prison. Urban blacks will be exiled to it, far from their friends and loved ones, and be guarded by rural whites. America is predominantly urban. So are its prisoners. The lifestyles and values born of the cultural, ethnic and racial aspects of city life are often incomprehensible to the white, rural, protestant-ethic guard. The resulting understanding gap is far wider than the miles which separate city dwellers from farmers. Surely Attica, and more recently Pontiac, have made this abundantly clear.

Prisons fail because they are places where the few have to control the many. In the outside society unity and a sense of community contribute to personal growth. In the society of prisoners, unity and community must be discouraged lest the many overwhelm the few. In the world outside, leadership is an ultimate virtue. In the world inside, leadership must be identified, isolated and blunted. In the competitiveness of everyday living, assertiveness is a characteristic to be encouraged. In the reality of the prison, assertiveness is equated with aggression and repressed. Other qualities considered good on the outside — self-confidence, pride, individuality — are eroded by the prison experience into self-doubts, obsequiousness and lethargy.

Prisons fail because we as a people use them as non-solutions to our most sophisticated problems. Monumental revolutions have changed the nature of life in our country — the automobile with instant mobility; television with its glorification of material things, of crime and of violence; the racial and sexual revolutions that brought unfulfilled hopes; Vietnam and Watergate which infected a whole generation of young Americans with alienation and despair; the pill with the resulting changes to sexual mores and even to marriage and the family; chronic and massive unemployment and underemployment which have become a way of life. All these and other forces have hit this society with the impact of an atom bomb. Individually, and in combination, they contribute to the great increase in crime — an increase to which we have responded by locking people up as never before in our history. No other Western industrial nation comes close to us in its use of the prison as a method of social control. This “land of the free’’ has, as a result, developed Western civilization’s highest rate of imprisonment. And while America leads the world in this unworthy statistic, the South leads America.

Prisons fail because they are based on the assumption that behavior can be controlled by sufficiently raising the cost of misbehavior. That assumption holds, in cost-benefit terms, that repression is cheaper than opportunity. Any institution so conceived and so dedicated should not — must not — endure.

It is my view, frequently expressed, that this nation’s principal commitments during the rest of this century should be toward reducing crime by correcting the crime-producing conditions in our economic, racial and social structures. At the same time, the various states must revise their criminal codes by removing sanctions against a whole range of behavior which causes injuries only to persons so behaving — the “victimless” crimes. Sentences must be made more equitable and shorter, with imprisonment viewed as the sanction of very last resort rather than the sanction of first resort. All of this will require the development of a national “mind-set” which permits us to abandon, or greatly limit, our raw punitive impulses.

Tags

William Leeke

William Leeke has been working in corrections since 1956 as a teacher, warden, deputy and commissioner. He has served in his present position of Director of South Carolina’s Department of Corrections since 1968. Currently president of the American Correctional Association, Mr. Leeke has also presided over the National Association of State Correctional Administrators and the Southern States Correctional Association. Considered a liberal among Southern prison commissioners, Mr.

William Nagel

William Nagel has been the executive vice president of the American Foundation, incorporated, and director of its Institute of Corrections since 1969. He also served as vice chairman of the Governor’s Justice Commission, Pennsylvania 's criminal justice planning agency. He began his career as a case worker for the Pennsylvania Prison Society.