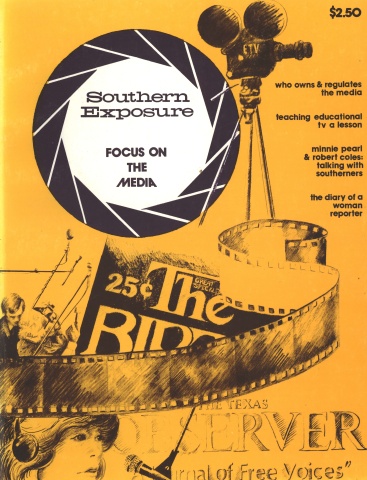

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

Mrs. Henry Cannon is finally living the life that has been denied her for over thirty years. There are no deadlines to meet, no planes to catch or miss, no early morning radio shows, and no one-night stands at the fairgrounds. She plays tennis and bridge, has friends over for dinner on Saturday night, and does her church work. She likes this kind of life, but sometimes she gets restless. So, occasionally Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon pulls out a pair of scuffed-up Mary Jane shoes, a frumpy old ruffled dress, and a straw hat with a dangling price tag, and slips away to find her best friend, Minnie Pearl.

Sometimes she'll head out to the new Grand Ole Opry House or catch a plane for an out-of-town appearance, but it's just as likely to be a local hospital or church to entertain some patients or regale the Senior Citizens. As long as Sarah Cannon doesn't get too sure of herself, Minnie Pearl stays with her, doing what she does best — making people laugh.

Minnie Pearl is a trouper. She has been at it for almost 37 years. She stands there all dressed up in her finest organdy dress, spinning tales about Grinders Switch and poking gentle fun at herself, or her brother, or that other important person in her life, her "feller.'' She's a comfortable sort, a country girl who looks like she came in by mistake, so "proud to be here" that she forgot to remove the price tag from her new hat. Her naivete and innocent blunders often remind us of our own human frailties and lack of sophistication, yet there's reassurance in the fact that Minnie doesn't seem to be embarrassed in the least. As Sarah Cannon would say, "She doesn't mean any harm."

Comedy has always been an integral part of country music. Early touring bands had a medicine show quality about them, often using humor as a wedge to introduce their music. The Grand Ole Opry, in addition to featuring stand-up comics like Whitey Ford (The Duke of Peducah), Rod Brasfield, Archie Campbell and others, has traditionally featured artists that combine comedy and music, such as Unde Dave Macon, Bashful Brother Oswald Kirby, Stringbean (David Akeman) and Grandpa Jones. The influence is still evident today in Speck Rhodes, the comedian/musician who appears with the Porter Waggoner band.

In the early 30's, Sarah Colley was only vaguely aware of the Opry and her peers in comedy. Her goal was to break into serious show business; she dreamed of her name in lights on Broadway. But the Depression was no time to make it big, and lack of funds forced her to return to her hometown of Centerville, Tennessee, after graduation from Ward-Belmont College rather than pursuing her studies in dramatics.

Her itch for the theatre persisted though, and two years later she joined the Wayne P. Sewell Company in Atlanta to travel throughout the region directing and coaching amateur productions. One of her productions took her to north Alabama where she stayed with "one of the funniest women / ever met." She was so influenced by the woman that she began collecting country stories and songs to advertise her plays by giving an imitation of "the mountain girl." In 1938, at an appearance before the Pilots Club in Akin, South Carolina, the mountain girl was outfitted and named:

I went down to a salvage store and bought a sleazy, cheap, old yellow organdy dress, a pair of old white shoes, and a pair of white cotton stockings and an old hat and put some flowers on it ... I walked down through the crowd and they didn't know anymore than a jackrabbit who I was or what I was doing ... I was just speaking like an old country girl that had come in by mistake.

Minnie Pearl was well received that night in Akin, but two years later Sarah Colley was back home in Centerville again —broke, no job, and a widowed mother to support. She got a job with the Works Projects Administration (WPA) running a recreation room and occasionally would be asked to "do that old silly thing" at social functions. It was an unhappy, miserable time. Finally things began to fall in place. A chance performance at a Bankers Convention led to an audition with WSM and a subsequent invitation to join the Opry in 1940. One year later she was touring with Pee Wee King and his Golden West Cowboys as a part of the Camel Caravan, which covered 50,000 miles in 19 states to bring country music to hillbilly servicemen scattered across the country. Her "Howdy, I'm just so proud to be here" quickly endeared her to WSM's vast listening audience, and she soon established herself as the first lady of country comedy.

In 1947, she married Henry Cannon, a private airline pilot. For the next twenty years they worked closely together, taking Minnie Pearl on a relentless tour of one night stands, always arriving back in Nashville in time for the Opry on Saturday night. It is obvious that Henry Cannon has been an important person in her life. She speaks of him often and feels that he has been of particular importance to her work because of his own sense of humor. It was at his suggestion that she agreed to semi-retirement five years ago.

The following interview was taped at their home in Nashville in late November of 1974. Mostly it is the story of Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon and her persistent search for the golden ring; it's also the story of her best friend, Minnie Pearl, and how together they settled for "second best."

— Sue Thrasher

“I Was Just Insufferable!"

When I was a little girl, Daddy always had the Grand Ole Opry on —starting in the late 20's, that's my earliest recollection of it —but I don't remember actually caring about the Grand Ole Opry. When I would hear it on Saturday night, it was an accompaniment to a lot of other things. I don't ever remember stopping and listening to country music. I knew that people went to square dances and things like that, but I wasn't particularly interested because I knew it so well.

I rejected the idea of country music, you know, because I was born and raised in it, and I was looking for farer fields. I wanted to be in the pop end of the music business. I played a little, sang and danced, and had talents in several directions. I didn't want country music at all. I wanted to be an actress. 'Course I wasn't supposed to be one, but I thought I was.

My parents didn't really want me to, but they didn't oppose my being in the "legitimate" field as we called it. Mama would have thrown up both hands in horror if she had known I was heading in this direction as far as being a comic was concerned. Mama frowned on my tendencies toward comedy — and they were always there, even when I was going to be in serious show business. I guess even at that age I had admitted inwardly to myself I would take it anywhere I could get it, anytime, just to be on the stage.

I was the youngest of five children. My four sisters were much older than I, and they put me up to show-off all the time, even when I was a kid. I was in my first recital when I was eighteen months old, sang in a music recital. I was just insufferable! And was all my life as far as wanting to show off was concerned. I just finally got to channel it and harness it and put it into a vehicle.

When I finished high school in 1930, Mama and Daddy offered me four years at some state university or two years at Ward-Belmont, a fashionable school in Nashville, where I could get what I wanted in dramatics. I took the two years at Ward-Belmont which I have never regretted. I think it was the beginning, really, of Minnie Pearl. To begin with, it was during the Depression, and everybody had money, I thought. I mean it was a lot of money to me. Where I came from everybody was broke, and where most of these girls came from everybody was broke, but these girls were rich. The place was elegant and I felt ill at ease. Our old house was just marvelous — gingerbread and gables on the side of the hill above the river where Daddy had his sawmill. It was full of laughter and fun and foolishness. All the furniture was worn out; we couldn't keep it any other way with five children. But at Ward-Belmont, I quickly realized that I couldn't compete with the other girls. I just couldn't compete with their clothes, their spending accounts, and their know-how. I was so much from the country, and so country. It was just the greatest place in the world once I established the fact that I would have a place. But I didn't have a place. So I had to find a place, and in doing so I resorted more and more to comedy.

I had an excellent teacher, Miss Townsend. She spent two years trying to convince me that I didn't have a sense of humor. She didn't think I was funny, and she goes along with thousands of others. You see, she didn't care for my sense of humor! She was more inclined to like a subtle sense of humor. She was under the impression from having talked at length with my teacher at Centerville — my expression teacher as we called it through high school—that I seriously wanted to be an actress. Miss Townsend's job was to bring out whatever latent talent I had —which she couldn't seem to find—but she thought it was there because Miss Inez Shipp, my teacher from Centerville, had told her I had it. Well, what Miss Inez was probably telling her was that I probably had as much talent as any child in that little town of 500.

Looking back on it now, I'm sure there were lots of talented children, but I was the only one that had the brass, the whatever, to get up and do it. I would get up and do anything, it didn't matter. All the plays that came through, I would be in them. I didn't care whether I could do what I was supposed to or not. I would just say I'll do it. Any chance I ever got to perform, I performed. It didn't make any difference whether it was singing, dancing, or reading, I would do it because I loved to go on stage. I just loved the audience. I still do!

Really, I was a born mimic. When I was a little girl if they had a singing recital or something, I would come home and the next day or night I would entertain my family by imitating the people — how they would walk out on the stage, how they would sit, how they would take their bows, you know. I was just a clown!

So at Ward-Belmont I established a certain — oh, what you might say —a beginning for Minnie Pearl. I realized I was not going to be able to play it straight. I knew I was going to have to do something. Then Miss Townsend more or less assured me of the fact that I didn't have all that talent. She died before I became Minnie Pearl, but looking back on it and knowing her as I did, she would have sooner or later steered me over to one side. She would have told me I didn't have the talent. I am not a disciplined actress, and I could never have become a Helen Hayes, or a Katharine Cornell, or any of the people that I adored at that time.

"They Laughed Pretty Good That Night"

After graduating from Ward-Belmont, I went back home to Centerville and taught for two years. Worst time in my life. I didn't want to go back; I wanted to go to the American Academy, but we didn't have any money. I didn't want to teach; I wanted to get out. I was still fretting against this business. I knew I had something, but I didn't know what to do with it. There was a company down in Atlanta that had been sending coaches around putting on amateur plays and stuff, and I saw that as a way out for awhile. I worked there for six years. I went around all over the country, and that is how I got involved with Minnie Pearl.

I went to a place in north Alabama and stayed with a lady and her husband and son. It was in the winter of 1936, and I was down on my luck. I thought she was one of the funniest women — I still do — I ever met in my life. And I came away talking about her and imitating her and telling her jokes. They weren't jokes; the things she told were just funny, they weren't things she would make up. I had to advertise my play at the different towns that I went, so I would do an imitation of her.

But, you know, I still never listened to the Opry or any country music. I didn't have time. Even in 1936 when I was going to come on the Opry in 1940, it was completely unknown to me. I don't think I have ever told that to anybody before, but it's true. I never thought of it really. You would think that my interest in old country songs and stories would have made me listen to the Opry on Saturday night, but I was always working on Saturday night, or traveling. So, I never did.

I traveled mostly in the country; these shows that I put on were country musical comedies. I had put on a play in Akin, South Carolina, for the Pilots Club, and they asked me to come back for their convention in a couple of months and do this "silly thing that you do." They said they would give me $25 and my expenses. That was just enormous, so I said, "Why certainly, I will do it." I had an old boyfriend over in that area, and I thought I could kill two birds with one stone. So I came back, and that was the first time I appeared professionally as Minnie Pearl, the first time I put her in costume. It was 1938. I went down to a salvage store and bought a sleazy, old cheap yellow organdy dress and a pair of old white shoes and a pair of white cotton stockings and an old hat and put some flowers on it — no price tag, that didn't come till later. I appeared that night in the ballroom of the Highland Park Hotel, which was a very swank hotel. I walked down through the crowd and they didn't know anymore than a jackrabbit who I was or what I was doing, but the rapport was there. I walked down through the crowd, and I was speaking just like an old country girl that had come in by mistake. They were just . . . you know . . . they didn't have any idea what I was doing.

But anyway, they laughed pretty good that night. I used a few stories about Grinders Switch. I told them about brother, and I used several jokes about my feller. My feller has always been tantamount. He is very important to establish the gag of my unattractiveness. I came away from there that night with a prescience . . . I'm not saying that a light shone and a voice said this is where you are going or anything like that, but it was being borne in on me gradually . . .

Daddy had died in '37 and Mama had some vicissitudes, so I came back home in 1940. Back to my hometown where I had started—a failure at 28, not married, no money. I got a job with the WPA setting up a recreation room in an old building upstairs over some stores. I was alone and frustrated, and dabbling with Minnie Pearl just wherever she could be used — but never for any money. And that bugged me, because of all things I wanted money so I could get away. But I couldn't put her out: I couldn't merchandize her. I thought then that I would develop her and use her as a springboard to get money to do the other act. And it's a wonder the Lord let me have her, because that's a misuse. That's a betrayal. But He was good to me. I looked around me at the people in Centerville, and I just thought my life was over. Pretty depressed. I look back now and think how different my life would have been if I had married some nice fellow and settled down and had children in the normal way that people are supposed to.

It was a funny thing, I sort of had the feeling ... I couldn't see where I was going, and I see. people like that now and my heart goes out to them. I know why they drink a little or they take a little something, because everybody in the back of their head has a certain way they want to go, and if they don't get there, they think they have failed. If they could just see that the second best is sometimes better than the best, which mine was. I still had that idea of having my name in lights on Broadway and all that jazz which is just hallow. It's still great, but it's hallow. The lights go out and the grease paint comes off, and you have to have somebody to go home to, which I was fortunate enough to find, but it was late.

"You Are Just Not Grand Ole Opry Material"

Anyway, one afternoon, I was sitting up there in that old place, and it was dirty — the place not me —and this man, this banker that had lived in Centerville for years, came up and said, "There's going to be a Bankers Convention, 'Phelia. Haven't you got some children that you've been teaching to sing and dance?" Well, that was against the rules, and I didn't know anybody knew it. You weren't supposed to do that, but I was picking up a little extra money and cheating on the WPA. I had a bunch of children whose parents paid me $20-25 a month because they thought I was talented and there was nobody else in town that taught dramatics and dancing. I said, "Yeah, I'll let them do it." And he said, "By the way, that thing you do'—he didn't even know the name of it—'that you did at the Lions Club. You know, that old silly thing." I said, "Minnie Pearl." He said, "Would you mind doing that if the speaker doesn't get there on time?" And I said, "No, I don't mind." "Just kill a little time with it," he said.

It was just that accidental. That's the reason when people say they don't believe in God . . . so much stronger than we that leads us. If the man had gotten there, I would have . . . But he never was supposed to get there. So, I sent the children off, and got up in front of all those bankers — they were from all over the area —and I said, "I would like to do my impression of the mountain girl, Minnie Pearl. Howdy! I'm just so proud to be here." And they just fell out.

I was dressed in regular clothes. I had the costume at home, but I didn't know for sure I was going to do it. Actually, I hadn't used a costume but twice at that time. I wasn't sure that I wanted to get tied to a costume; I had gotten that far. Still, and I have never gone into this in all these years that I have been doing interviews, it's incredible that sometime during that summer I didn't become addicted to the Opry, isn't it? But I didn't. I was aware of it, but nobody said, "Why don't you put that thing on the Opry?" when they would see me do it. I guess they thought I wasn't good enough.

So, I went on back home that night and didn't think anything particular about it. I just knew it had gone well, and I wasn't conscious of the fact that it was any kaleidoscopic, fantastic night in my life. The following week I got a call from WSM, and they said that a man by the name of Bob Turner who was vice-president of the First American National Bank in Nashville and who knew my family and knew my situation had just gone to bat for me —told them I ought to be on the Opry. So, they called and asked me to come up, and I did. I thought the audition went terribly. I had never been before a microphone except these little old bitty things. I didn't feel at home. I didn't like performing in a dead studio with a bunch of strange men looking at me through a control room window, not cracking a smile and talking about me while I was working. But I staggered on through.

I finished on up and this nice man, Mr. Ford Rush, said, "Come to my office." I thought he was going to say, "Hon, why don't we forget this? You just ain't got it." When I went into his office, he said, "We don't think they will take you, but we are going to give you a trial. You can come Saturday night at 11:05. We only have fifty-five minutes of the Opry left, and most people are tuned out by then and we are not running a big risk, but we don't think they will take you because you are a little too slick for them. We know your background; Mr. Turner gave us your background. You've had two years in a very exclusive college; you've had two years of teaching dramatics, and you've had six years of coaching and directing amateur plays. You are just not Grand Ole Opry material." I said, "But you don't realize I came from Hickman County. Have you ever been down there? That's the country."

So, I went on the Opry that night and Judge Hay was so sweet to me; he was such a lovely man. He said that night when he saw me I was so scared. See, I was entirely sure of myself so far as a live audience was concerned, and we had it at the old War Memorial Building. But there weren't that many people there on that November night. They had sort of drifted out, and they were about half-asleep. You know, most of them were seasoned Grand Ole Opry listeners, and they weren't ready for me. That first night I went on, I was never on such uncharted seas. To begin with, radio was a new medium.

I was so dumb I didn't know what I was doing, and that is what saved me. I didn't know how big the Opry was; I didn't know how big the audience was. I didn't know anything about it. I just knew I was going up there and say what I had to say, and I was saved by ignorance.

"She Has All the Qualities I Wish I Had"

You know, after things got pretty good for me, I talked to those men who had auditioned me and said, "What in the world did you see?" Where could you find Minnie Pearl? Was she covered up by my uncertainty and frustration, my insecurity at not having any money or position, not having a name and never having been in show business of this kind? Where did you find the girl—the delightful, sweet, lovely person she is? She is. Minnie Pearl is one of the cutest people I ever knew. She is funny and she's nice.

We were talking about her. I speak of her in the third person. I had some interviews when I was at Disney World recently, and this boy from Orlando, a pretty clever boy, said, "You speak of her in the third person." I said, "Yeah, I have been for many years. She is so much nicer than I am; I like to talk about her because she is warm and friendly, and she has all the qualities I wish I had — no prejudice, she never gossips, she never bears false witness, she never does any of the things that you are not supposed to do. She is pretty near perfect, you know, and I like her." This young boy looked me straight in the eye and said, "Does she like you?" It scared me so bad I haven't been able to get over it since. I don't know whether she likes me or not. Reckon?

She likes parts of me, but she dislikes parts of me. I can tell when she doesn't like me. She won't come around. I get up to perform and she is not there. She just drifts away like a little wisp. She goes on about her business and I call her and try to get her back but she won't come. Then some times I get up to work and she's clamoring just like my poodle. She's so eager, she just can't wait. And she is so funny, she knocks me out.

I made an appearance the other day . . . where was it? Some free appearance — that is when she is usually her best, when I am performing for a hospital, or a nursing home, or for somewhere she feels at home. Oh, it was the Senior Citizens the other night. I went out to the Waverly Methodist Church for a friend of mine. And she was so funny. It was like I turned her on, and she ran like that tape machine. I wasn't even conscious of it, you know, I thought of old gags I haven't thought of in a hundred years. And people just fell on the floor! I got up to read from this little book I have called Christmas at Grinders Switch and I got to quoting her, and she was just so in front of me I couldn't get around her. She didn't want me there at all; she was just telling me to go on and get away. She was just so silly! I thought, my goodness gracious alive, I wish I were working Carnegie Hall tonight. But she doesn't care for that; she wouldn't have been as funny. She felt at home at that church because, you see, Minnie Pearl does most of her performing at Grinders Switch at the church social.

I've played Carnegie Hall twice, and I've played Madison Square Garden and I've played some of the big places, and I have played a lot of little ones. On nights when I am going to have a big, big deal, I court her. Oh, Lord, please let her come around tonight. I need her, Lord, help us, I need her! I don't ever know if she is going to be there or not. She sometimes is; sometimes isn't. I worked Carnegie Hall for the first time and it was real fine, because I was frightened, and when I am frightened, she comes around. She tries to help me, but let me be a little too smooth and a little too sure of myself and she says, "Well, take it, you've got it. You are too big for me. I don't want to have anything to do with it!" And she is gone. I have to just get up there and struggle around. My timing just goes haywire, and I can't do anything about it. I can't find her. She's not there.

"Sometimes I Feel Like I'm Not At The Opry"

I did twenty-seven years of one-nighters. Twenty of it with Henry and seven of it before I met him. I was doing package shows mostly, and then part of that time I had my own show for the fair circuit. I did 55 fairs in the Midwest one summer —The Minnie Pearl Show. But I prefer working as a single with a package show.

Now I go to the Opry when I want to. They are kind enough to say I can come anytime I want to. They don't care whether I come or go. When I got off the road, I had just imposed on Henry so much he just got tired of it. It was more for him than anything else; he asked would I mind taking a sabbatical. So, I go or I don't go. They call me every week to ask if I'm coming, and I say yes or no. I don't feel exactly the same, and when Acuff is gone, it is going to be increasingly hard for me to go, although he will probably outlive me. He is a very remarkable man. Roy is 70, ten years older than I am.

But I don't know. Sometimes I go down there, and I feel like I'm not at the Opry, depending on who is there. There are so many young ones that I don't know. And they are kind to me, but it is not the same. I don't want people to be kind to me, although I appreciate it. It has to do with the comradery that has existed all these years between all of us that have kidded each other so. Like when I first came on the Opry I thought I was so good, and they knew it. So, they decided they would take me down, and they can do it. I came off stage one night and I had taken two encores and was waiting to see if I was going back, and one of the old-timers, Robert Lunn, came up to me and said, "Minnie Pearl, have you been on yet?" And everybody just died laughing. That was thirty years ago.

I became accustomed to the excitement and the glamour and to the fun and everything. In the old days I used to go down there and stay all night. I just couldn't wait for time to go down there. Then, I got tired —not of being on stage, but of meeting the deadlines. I was tired; I wanted rest. I took up tennis, and I began to want to stay at home. I had neglected my family and my friends, and I just wanted to settle back into a sort of return-to-the-womb type thing. I wanted to have some of the life that I had never had. See, I left home when I was 21, when I went on the road with Mr. Sewell and here I was 56 or 57 — never had had any of this kind of life, and I kind of like it.

"The Most Relaxed Section of Town"

We've talked a lot about the changes from the old days, about the new Opry House and the music. When I listen to the radio on Saturday night, there is a presence that is different. There is a technical difference in the echo of it. They now have one set of engineers who handle what is going on inside the building and another set of engineers who handle what is going out across the country. Well, when I came here they had a control booth back there and they had two men in it, and whatever came out went on the air. They didn't have anything to lower the decibility of this, that, or the other. It was just there and they put it out. And it was just great! But now you can't do that; you've got to have all this different stuff.

When I listen I have the feeling that the people are a little more dignified. They feel a little more constricted. In the old building they were eating popcorn and pulling their shoes off and the place was conducive to an awful lot of informality. Mothers nursed their babies; girls and boys courted and kissed and cuddled; drunks staggered in off the street and hollered if they liked something. One night during World War II, a boy from Fort Campbell decided that he wanted to tell his folks in someplace like Iowa or Kansas that he was at the Opry and he just jumped on stage right in front and said, “I want to say hello to my parents." They said, "We're on the air." He said, "I know you're on the air; that's why I want to do it." They had to get the security to take him off and he still was saying it all the way along. He said, "I don't mean any harm, I just want to tell them I'm here."

There was a feeling of informality that was different. Now the people come in from away off and they go in out there and go through that stile and all the way into the other and into that building, and by the time they get in there, they have been more or less screened. There is no place down the corner where they can get a beer. They can get food and soft drinks and everything like that, but it's an entirely different atmosphere. The old Opry was down there on Fifth Avenue and it was just in the very . . . what we might call just the most relaxed section of town.

But the change was inevitable. The old house as much as we loved it, had lived out its expectancy. It had done all it could do for us and it couldn't be air conditioned. It was dirty — ingrained dirty — there was no way you could paint and clean, and do all you wanted to do. The place had outlived its time, so it was time to move. I cried a little when we left, but I just got sentimental thinking about the different people I had known there. The ghosts seemed to be sort of sticking their heads out around the curtains.

Now we are getting nothing but compliments about the new building and it is beautiful. It's fun to have plenty of room to dress and have a comfortable place for people to sit. It was primarily for the fans that I was happy. When they come to stand in line for the second show they are under cover. The whole thing is on a very, very pleasant, nice level.

The music . . . there is an awful lot of talk here in town now about the change in the music. Well, I have been listening to this all along, and Roy and I were talking the other night about these people saying, "They are not keeping it country. They've got to keep it down close to the ground." Old Judge Hay used to say, "Keep it close to the ground, fellows." Well, there is never going to be a time when there won't be change. We have change in everything. Our country is changing now; it is in a period of change that has never been comparable. I don't know of anytime in the whole history of the United States where we have had as much change, but then I wasn't living back during the War Between the States. That was a big time of change; certainly nobody ever thought brother would fight brother. We had great change at the time of the Depression in 1930. I remember when people said that was the biggest change the United States has ever had — people shooting themselves and jumping out of windows; wealthy men standing in bread lines with a cup in their hands just begging soup. Well, that was a big change. Now we go into this where we have Watergate and the President is disgraced. A man is put up for Vice-President and they wait and wait and wonder if they are going to put him in. It's just all different.

Country music is written by people who are aware of this change. They are being influenced by this change and you can't expect people to sit like the old timers did that wrote "Great Speckled Bird," "Wabash Cannon Ball," and "I'm Walking the Floor Over You," and all those old-time songs. You can't expect people to sit in a vacuum and write songs like that when the world is crashing around them. It is inevitable that we should have this change, and I am not worried because country music has withstood all these other changes. We started our Opry in 1925 when things were going great. The crash didn't come till '29 and it weathered that. It weathered World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War — it has weathered everything and it is still going to weather everything.

It will change. And you say, "Well, do you like it?" Well, what difference does it make? I can't change it, and I don't want to change it. There will always be a part of it that will be like the old time to me.

Tags

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)