This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

My childhood memories of Virginia don’t seem to count. Some formative process doubtless was at work, but it was soft and effortless, as in a cocoon. The only thing about the years in Virginia that comes to mind is that my father, an army officer, always disagreed with other army officers about two things. The first was about Roosevelt. My father loved Franklin Roosevelt. The second was that in the next war America wasn’t going to fight the Bolshevik Russians. The U.S. Army officer corps was pretty serious about fighting the Bolsheviks. But my father said we were going to fight the Fascists — Germany, Italy and Japan.

One or the other of these two topics, the New Deal and the Coming War, was usually the center of discussion at dinner all through our Virginia years in the early 1930s. Not that I grasped these matters with great subtlety. For me personally, the first fragile awakening of self into the surrounding world of one’s provincial origins did not come in Virginia; it came when we moved to Texas in 1936. At the age of eight, I discovered football, Texas-style.

The first thing I learned about those Texans was that they liked crowds. Many years later, as an editor of the Texas Observer, I would realize that the crowds were mere effect, a manifestation of a much more organic tribal folkway that was central to the very way of life of the state. Football was no mere two- or three-hour pageant on an autumn weekend: it was an instrument of psychic survival and, as such, a centerpiece of the regional culture.

In places like Brownwood and Odessa and Big Springs, and even in small places like Olney and Rockdale and Sonora, the Friday night high school football game was a civic celebration, a rite of passage not merely for the male teenagers on the field or the female cheerleaders on the sidelines, but for the whole society. Towns of 5,000 population had football stadiums that seated 6,000 and regularly bulged with 7,000. Middle-aged parents, men and women in Western shirts and blue jeans, helped Grandpa and Grandma up the steps to the thirtieth row, the barefooted kids running ahead, the last-born in Mama’s arms or hanging tightly to her hand. The mayor was there and the town banker and the local wildcatter, indistinguishable in their stetsons and boots from the clerks and ranchers and roughnecks who worked for them or were mortgaged to them.

In the eastern part of the state — the piney woods — the cast and the power relationships were the same, though the ranchers there were mostly farmers. In the east, though, the ritual was a little less intense, a little less transcendent, for there were other things to do sometimes. Friday night at the high school stadium was still the high point, but it wasn’t everything. Fishing and hunting in the creeks and pine forests offered additional varieties of ritual.

But in West Texas — in the world of the Great Plains beyond the Edwards Plateau — the streams and forests had shriveled into dry arroyos and trackless land marked only with scrawny mesquites. In this stark country, the wind blew endlessly and the sand beat against clapboard, sifted under the sills and into the furniture and even into the food. Mostly the sand and the wind beat against the people and into their skin pores, a silent unseen intimidation that produced leathery faces and a fear in the soul. The plains wind haunted the women, gnawed at the men, as if to insist endlessly that they had no business being there, that this was the land of the Comanche if it belonged to any humans at all.

You had to move through this world slowly, live in it awhile, to know that the loud shouts and rowdiness of the people were more than some kind of peculiar regional heartiness. At root, it was a desperate defense, a fragile assertion of hope and defiance against the plains wind and the searing, dry summers and the dry raw cold of the winters. Here, football had become the collective defense, the celebration of community, a ritual proclamation not only that “We are here!” but that “We are prevailing!” In Plano and Rawls, in Jackboro and Montague, the Friday night game and the astonishing pageantry that surrounded it represented a tribal assertion that the people were winning their struggle against the land and the wind.

You had to know this to understand the uneasiness that settled over a West Texas community whose high school team was having a bad season. I remember a time in the 1950s when, on a trip for the Texas Observer, I discovered in one of these West Texas hamlets — I think it was Childress — a kind of pervasive lethargy. It was as if the local economy had endured one too many years of drought, as if the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression had never really ended for these people. Cautious outsider, I gently inquired about how things were. The answer, from a druggist, from an old rancher, from a filling station attendant, was that the team was no good. “We got stomped 39 to 0 Friday night. It was plum pitiful. Them boys couldn’t wrestle a damn nanny goat to the ground.”

In such a setting, one couldn’t get down on “them boys” too hard, for “them boys” constituted the next generation in the struggle against the wind and the land. So what the visitor heard was, “Them boys ain’t been taught proper” and “They gettin’ off the ball too slow.” The answer — the iron law of autumn politics in West Texas — was: “We got to git us a new coach.”

I knew none of this in 1936 when the family came to Texas, the soft rhythms of Virginia still informing my ways of thinking. But the attempt at socialization, the effort to turn Southerners into Texans, began, I now understand, right away. In the very first year, the Austin Maroons became a principal focus of my leisure. The tailback had the marvelous name of Travis Raven. (Ah, the names were regional statements: Kyle Rote and Yale Lary and Chal Daniel and Doak Walker — names for football players.)

Truly, these were the magic years of my childhood, from 1936 to 1941, from eight to 13. Horatio Alger, I came to understand, was real. Let me recount the story and you, too, will believe.

It needs to be said at the outset that there is not too much Wonder associated with the Austin Maroons. Glory, yes, but not Wonder. The Austin Maroons were already at the top when I found them in 1936 — at the absolute top, like second-generation robber barons. When Travis Raven graduated and went off to college, somebody found a boy out in the countryside who was big and strong and fast. Somebody else gave his daddy, a tenant farmer, a job in Austin and the boy moved into Travis Raven’s slot at tailback. A fitting anonymity surrounded all this: the new star was named “Jones.” The Austin Maroons clobbered everybody with Raven and they clobbered everybody with Jones. For years, they ruled effortlessly as champions of District 15-AA. Glory, but not Wonder.

Horatio Alger lived on the other side of town — at the University of Texas.

Friends and neighbors, we started in rags. Winless. Absolutely winless. The forces of the culture beat down on us poor folks. SMU and TCU and Rice and Baylor all manhandled the state university. The Eyes of Texas weren’t on anybody. We looked at the ground in front of us, heads bowed in weekly humiliation. You people at Notre Dame and USC and Michigan don’t know how it was, in poverty. Let me tell you, it was diminishing. It made you feel poorly. It made you edgy. You got laughed at and people patronized you. It wasn’t nothin’ to be a Longhorn.

The story really begins in late November, 1936, the last game of the year. Thanksgiving Day. The Traditional Game against the “other” state university, the Aggies of Texas A&M. It is very important that you understand about “the Tradition.” The Tradition was that the Aggies had never won in Austin. Not since Memorial Stadium was built and dedicated, in a game against the Aggies, way back in 1924. Now then — when you are eight years old — that is some Tradition. The Aggies never won in Austin. Never!

But they sure were favored in 1936 because, as everybody knew, the Longhorns couldn’t beat anybody.

Well they did this time. I was there that day when old tradition just kept rolling along. Kern Tips of the Humble Radio Network said it just right: “When the long November shadows lengthened across Memorial Stadium, the scoreboard read Texas 7, Texas A&M 0.” That’s the way Kern Tips usually talked.

You know, of course, that the way up from rags isn’t all that easy. There were still plenty of hard times ahead. The Longhorns couldn’t win anything all through 1937. Nine straight defeats, culminating on Thanksgiving Day in Aggieland. Still on the bottom.

A float made of paper flowers said it best, in the spring Roundup Parade on the campus in 1938. I saw it. It had a Bible made of black paper flowers and a brown flower football and a student standing between them in a football uniform. On the side of the float were the words, “The Answer to Our Prayers.”

The answer, you see, was Dana X. Bible, the famous football coach, who had been lured away from Nebraska to bring the University of Texas out of the wilderness. There was a lot of talk about it because they gave him a 10-year contract at $15,000 per year and a lifetime contract as Athletic Director after that at $5,000 per year. In the Depression they did this. The only problem was that the President of the University didn’t make that much, so they raised him, too.

Boy, it was like a lightning bolt. Ole Dana Bible stirred up the alumni (they were pretty stirred up going in), and Bible and everybody else combed Texas and let me tell you they got some football players in there in 1938. That freshman team made everybody sit up and take notice. They had a big guy at fullback named Pete Layden and a tricky little guy at tailback named Jack Crain and they had a rangy end named Malcolm Kutner and they just beat up on folks. Everybody just couldn’t wait until 1939 when those freshmen would be eligible to play varsity football.

Especially after what happened to the varsity in that year of 1938. It was terrible — they just kept right on losing. Every week. As September turned into October and then into November, that victory over the Aggies in 1936 was all we could look back on. We hadn’t won a game in two years!

The Southwest Conference was real big in those days, of course. Everybody in America knew that. When unbeaten SMU played TCU, the winner got to go to the Rose Bowl and the loser went to the Sugar Bowl. Slinging Sammy Baugh and his TCU team lost, but you can bet they won that Sugar Bowl game. And then in 1938, TCU had another great passer, Davey O’Brien, and all he did was take ’em to the National Championship. The Southwest Conference was the best there was. Everybody knew that.

For a losing team, you’d be surprised how good the Texas Longhorns played. Everybody said we had a starting lineup that could play with anybody in the country, including SMU and TCU. We didn’t have any substitutes, though. We could hold everybody to 0-0 through the half, or even through the third quarter, and then our boys would get tired and the other team would score. We lost a lot of games that way. But the worst trouble was we couldn’t kick any extra points. We scored in the very last minute against Kansas, but we lost 19-18. Missed three extra points! SMU, the same thing. We played a tremendous game, but we lost, 7 to 6.

That was the situation when we came down to that Traditional Game against the Aggies in Austin in 1938. You have to understand that there is a real villain here. His name is Harry Viner, and his part of the story started in 1937 when Rice Institute came to town. Texas had it won late in the game when this Rice guy threw a long pass that bounced in the end zone and then into the hands of a Rice player named Frank Steen. It was incomplete — the ball bounced on the ground just before this guy Steen picked it up. But the referee ruled it complete! The referee was Harry Viner. They almost had a riot that afternoon. The papers next day called the Rice end “One Bounce” Steen. But that wasn’t anything compared to what everybody called Viner. We’d have won a game in 1937 if it hadn’t been for Harry Viner.

That was how things stood on Thanksgiving Day in 1938. We were worried. Burt Newlove, who lived next door to me, said there wasn’t any way Texas could win cause the Aggies had a real good team, not quite as good as TCU, the national champions, but right up there. Rexito Hopper and his brother, Jackie, were like me. They were hoping. But Garland Smith was with Burt. Garland said that old Tradition was going down for sure this time. Course, they hoped it wouldn’t, you understand. We all were for the Longhorns. That was like being for Roosevelt. It was just too bad those marvelous freshmen that Dana Bible had couldn’t play. We really needed them.

Here’s what happened. Burt and Rexito and I were in the 25-cent Knot Hole Gang section, in the end zone, and saw it all. That stadium was packed. Forty thousand people. And Texas played inspired football. They drove down to the Aggie five-yard line. They drove down to the eight. They drove down to the six.

But they couldn’t score.

Once, after Texas had been stopped short on fourth down, somebody said they should have tried to kick a field goal. But that didn’t make any sense at all because everybody knew that Texas couldn’t even kick an extra point, let alone a field goal.

Anyway, in the second half, Texas was just as inspired. The Longhorns stopped the Aggies cold, but they still couldn’t manage to score. One of the troubles was the reverse to Puett. We had this player in the backfield named Puett. He only carried the ball on a reverse, which was not often. Most times he didn’t even get back to the line of scrimmage. They’d just see that old reverse coming and they would clobber poor Puett. Especially on fourth down around the Aggie goal line.

Well, late in the game, we made one last drive down to their ten-yard line. The fullback made two. Then the tailback made five. I remember it exactly. I felt pretty good because we were down on the three-yard line, and we had two more plays to buck it over. One to get it right down to the goal line and another one to buck it right on over. I remember thinking that, while standing there (believe me, we were all standing!) in the Knot Hole Gang section in the end zone.

You know what happened? On third down they gave the ball to Puett on a reverse. He started to swing outside like he always did, but then he cut right upfield. I could see the hole. From the end zone, you can see holes easy, even when the teams are at the other end of the field. When he got to the line of scrimmage he just dove. High. He was three feet in the air, his body all strung out parallel to the ground. Touchdown! There’s a newspaper picture of that, Puett soaring high with that Aggie goal line right under him! It was in every paper in Texas next day.

And they kicked the extra point, too! It just went right on up there, not exactly “splitting the uprights” like they say, but almost, and it was way up there, not just barely getting over the crossbar or anything like that. Texas 7, Aggies 0. Old Burt Newlove and Rexito Hopper and I just went wild, jumping up and down. Everybody went wild. The Tradition was going to make it!

But it wasn’t over. In fact, something really crazy and unbelievable happened.

With about a minute to go, Texas had the ball at midfield and the punter aimed the ball for the coffin corner and hit it. It bounced just inside the sideline at the one-yard line and went straight on out of bounds. Aggies on the one, with 99 yards of Memorial Stadium Tradition looking them right square in the face. They were whipped! But you know what? The referee ruled that the ball had not gone out of bounds. He waved his hands and said it had gone in the end zone. Dana Bible had a fit. Players ran off the bench and things got pretty hot where that referee was. That referee was Harry Viner!

There was a kind of scuffle — at least Harry Viner later claimed somebody pushed him — and he just marched that ball up to the 20-yard line and he kept right on marching. Harry Viner penalized Texas half the distance to our goal line. Crazy! Half of 80 yards is 40 yards! The place almost came apart. It must have been the longest penalty in the history of football.

But Texas stayed right in there. They rushed that Aggie passer off his feet and made him throw three wild, incomplete passes. The Aggies had to punt. The ball just hung up there lazily and came down and got killed on the Texas five-yard line. Less than 30 seconds to go.

Well, Dana Bible put ole Bobby Moers in there. He was an All-American, Bobby Moers was. But it was in basketball. He played guard. He was the greatest dribbler the Southwest Conference had ever had. And they put him in there at tailback and centered the ball to him.

Bobby dribbled it. On the ground. In the Texas end zone. And an Aggie fell on it! Can you believe that? In the Traditional Game. In Memorial Stadium. Where the Aggies have never won or tied even.

And so, of course, the Aggies kicked the extra point. But it never got there. The University of Texas blocked that extra point on Thanksgiving Day in 1938 on the last play of the Traditional Game. About four guys just poured in and one of them leaped up high on the backs of the others and put both hands out and that ball smashed into those two hands and rocketed right back upfield, right past the kicker.

We couldn’t kick an extra point but on Thanksgiving Day in 1938 we beat those Aggies 7 to 6 in Memorial Stadium. “We only won one game all year but those Aggies haven’t won in Memorial Stadium yet.” It was Golden.

Nobody left, of course. It couldn’t be allowed to end. People just stayed. The Longhorn band played “The Eyes of Texas,” and Burt and Rexito and I squared our shoulders and sang that song like we never sang it before. “All the live long day.” Yes Sir! And walking home, across Speedway Boulevard and across the campus and then up the drag and over to Rio Grande Street and up to Washington Square where we lived, visions swam in our heads and our lips gave wings to poems. Puett on a reverse. Puett on the Reverse for three yards, soaring into history, high over that Aggie goal line. Did you see old Puett fly, Rexito? Yeah, boy, I saw it! Boy, what a play! Boy, what a Game!

Can life ever again approach such a moment of ecstasy? Will there ever be a sight like that Texas line smothering that extra point? On the Last Play of the Traditional Game? Let TCU have the National Championship. We have the greatest tradition in the world: the Aggies do not win in Memorial Stadium.

And Harry Viner. A new tradition. Harry Viner does not referee University of Texas football games. Ever again. The end, Harry Viner. There is, in 1938, no question in our minds that there is a just God and that the American Republic is under the rule of law.

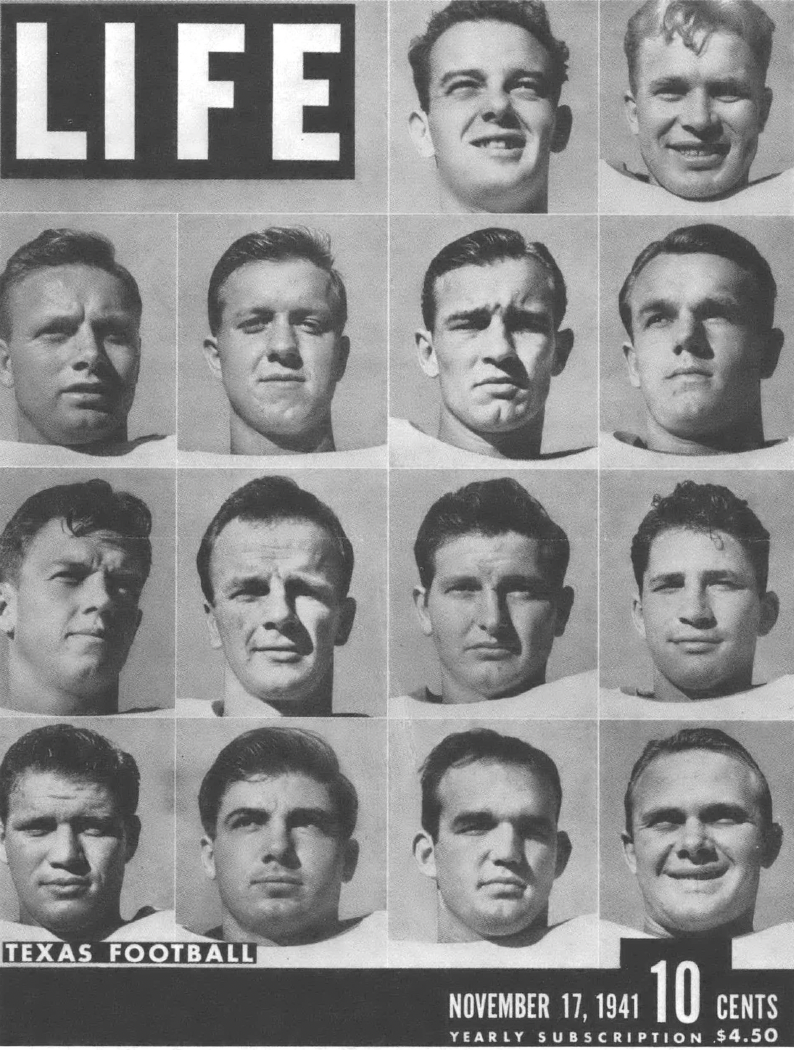

That was how it started. It marked the beginning of all the magic still to come over the next three years. The fabulous freshmen who could not play that day became the sensational, erratic sophomores of 1939, the maturing juniors of 1940 and what Life Magazine called the American “Wonder Team” of 1941. It was “the greatest college football team ever assembled.” The Wonder Team simply crushed people. They beat the fifth-ranked team in the nation, SMU, 34-7. Rice went down 40-0 and Arkansas 48-14. The Oklahoma Sooners surrendered 40-7. The magnetic moments, so many of them, fuse in my memory into a luminous hue, so that in harmony with the rising Rooseveltian economy we all seemed to be riding a special rainbow to the Good Life, Rexito and Burt and Garland and Larry, blessed children of this most blessed land.

History provides such concrete and persuasive evidence for our illusions. Did it not begin the right way in 1939, in the first game, in the first quarter, indeed, on the very first time Cowboy Jack Crain ever carried the ball in a varsity game — when “The Nocona Nugget” circled right end behind crunching blacking and ran 45 yards for a touchdown? Did it not begin that way, Horatio? The string of victories after that appeared to us like the predictable milestones of a Chosen People. Were not the unbeaten Minnesota Golden Gophers merely the nation’s number two team behind the Wonder Team? Was that not Crain and Layden and Kutner and Daniel on the cover of Life Magazine? Was it not our own intimate little neighborhood that the whole world looked to and honored? Bow down, Henry Luce, to Washington Square in Austin, Texas. Was not everything, absolutely everything, possible?

Yes.

All of the humiliations of bygone years had been erased, all the Harry Viners dispatched to the dustbins of history. Horatio Alger was real, all right. There was no justification for skepticism because the evidence that we were annointed was simply overwhelming.

But even the elect must labor at their calling, especially during a Depression. In the Knot Hole Gang, you could pick up empty Coke bottles off the concrete tiers and take them to a drug store not too far away from the stadium. You got two cents a bottle. Burt and Rexito and I used to pick up Coke bottles at the end of games, as many as we could carry, eight or nine if you worked at it carefully, and with this we mobilized enough capital for a post-game malted milk — if you didn’t drop too many on the concrete tiers. It is mid-October of 1939 — the sophomore year — and the Texas Longhorns, though now obviously on the road back, are losing to Arkansas 13-7 with 30 seconds to play. I am distracting myself from total despair by scavenging relentlessly. I now have a record number of 14 Coke bottles in my arms.

Suddenly there goes Crain, Jack Crain, Cowboy Crain, the Nocona Nugget, breaking to the outside, his 170-pound frame flashing past the secondary, skipping around those last two men, into the open — 70 yards for a touchdown. After frenzied spectators are cleared from the field, Crain “calmly” (that’s what the paper said) calmly kicks the extra point that brings Texas a 14-13 victory. On the way up, Horatio!

What I remember is that when Cowboy Jack started upfield, I had all 14 Coke bottles in my arms. I may have had them when he blurred past the last two Arkansas players. Then Burt Newlove is leaping on the seats in front of us and letting go a wild cry of utter triumph, and Rexito and I are jumping up and down in each other’s arms. When they tried to clear the field for the extra point, I discovered we were standing in about two inches of broken Coke bottles. It didn’t matter. Glory and Wonder in your eleventh year on the planet has not room for 28-cent setbacks. Our tragedies were subsumed in our blessedness.

Our childhood began to come to an end on a November day in 1941 when the impossible happened, when the Wonder Team, the Life Magazine cover team, was upset 14-7 by TCU, a day when Malcolm Kutner dropped a Pete Layden pass on the goal line, when Jack Crain slipped while breaking into the open. A jagged tear in the lining, one November afternoon in another century.

In the fading moments of that game, I remember learning something about religion, a subject in which I had not had much prior training. You prayed when things were out of your hands. “Catch it, Malcolm,” I prayed; then, that he would catch the next one. I prayed for Pete Layden to throw the next one. “Oh Lord, if You’ll just let Texas win, I promise I’ll . . .” The passionate bargains of the powerless. Horatio?

The end, the very end, was full of meaning that we did not recognize. While the Wonder Team was thrashing almost everybody, and losing to TCU and tying Baylor, the little old Aggies TEXAS FOOTBALL were edging by people so that when we met them on Thanksgiving Day, the unbeaten Aggies were already champions. They were the number two team in the nation, right behind Minnesota. It left us all a bit dazed. So the 23-0 Texas win over A&M was not the high moment of celebration it might have been. We were still only second in our own conference. It seemed impossible. It was like a soaring glider had come to rest in the middle of the sky. Things are just not supposed to end that way.

There was a fateful postscript. Texas, breaking precedent, had scheduled a game after Thanksgiving. It came against Oregon, a team that had just missed going to the Rose Bowl. At the end, in that final performance, the Longhorns were never more magnificent. It was as if the shattered dreams were somehow, for an instant, reassembled through one last blinding display of pure artistry and excellence. The Wonder Team was breathtaking. The final score was 71-7. From the Knot Hole Gang, it looked — and was — awesome.

Yet it was not enough. The season was over and the ultimate glory of the National Championship had slipped away somehow. The Play had Closed, to disappointed theatre-goers. In Sonora and Rawls and in Jack Crain’s hometown of Nocona, where West Texas boys had made the cover of Life Magazine, the people sat around and speculated about what should have been. And in Austin, Rexito and Burt and Garland and I would start sentences, “If only Kutner had . . .”

On the night the season ended, when the might-have-beens began, my father consoled us that “in the larger perspective” our difficulty was manageable. We learned, rather soon, that he was right.

The date of the Oregon game was December 6, 1941. We were 13.

Tags

Lawrence Goodwyn

Professor of history at Duke University and author of Democratic Promise, the landmark history of the Populist movement. (1990)

Larry Goodwyn teaches history at Duke University. His son, Wade, born in Austin during the family’s years with the Texas Observer, is currently a member of the Longhorn Marching Band. (1979)