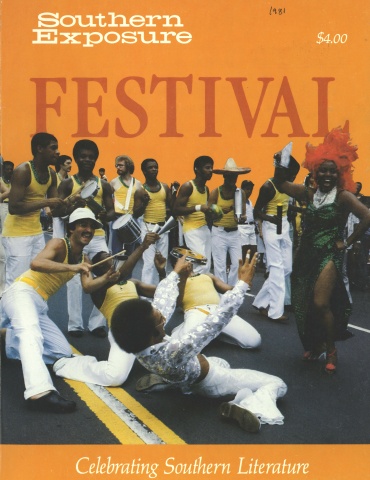

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Alice Walker speaks quietly, but with a powerful directness and intensity. She emits a warmth and a depth of character that captivates the audiences she frequently addresses, as well as the people who meet her casually. Yet Alice Walker is, primarily, not a speaker but a writer.

Born 36 years ago in Eatonton, Georgia, into a poor farming family, Walker attended Spelman College in Atlanta for two years before winning a scholarship to Sarah Lawrence. After college, she went to Mississippi to work in the Civil Rights Movement. During the last 10 years, her writing has chronicled Southern struggle and reflected her concern for the critical issues of race, violence, poverty and sexism. Recently she wrote in Ms. magazine that “A ‘womanist’ is a feminist, only more common,” and she identified herself as a “womanist.”

She explains, “I have trouble with having to say that I’m a black feminist when white feminists don’t ever say that they ’re white feminists. They say that they are feminists because it is assumed that they are white feminists, since the word feminist’ comes from their culture. I wanted a word that came from black women’s culture, and 'womanist’ comes from our culture. When I was growing up, when all of us were growing up, our mothers would always say, ‘You’re acting womanish,’ you know, when you were trying to act like a woman. And I like the way it feels in my mouth. I like ‘womanist.’ I always felt that ‘feminist’ was sort of elitist and ethereal and it sounded a little weak. I once mentioned that to Gloria Steinem, who said, ‘Well, maybe so, but our job is to make it strong.’”

Walker has published two novels, Meridian and The Third Life of Grange Copeland; a collection of short stories; numerous essays; and three volumes of poetry, the most recent being Good Night Willie Lee, I’ll See You in the Morning. And, she says, “I’m just getting ready for publication a new book called You Can’t Keep A Good Woman Down. It’s a collection of short stories, and I’m finishing a collection of essays called In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. And I’m writing a novel.”

This interview was conducted in late 1980 for Southern Exposure and for WRFG, a community radio station in Atlanta.

James Baldwin said that writers write to change the world. Why do you write?

I have written to stay alive. I’ve written to survive. That was from the time I was eight years old until I was 30. Then from the time I was 30 until now at 36 maybe I’m ready to change the world. Because I’m black and I’m a woman and because I was brought up poor and because I’m a Southerner, I think the way I see the world is quite different from the way many people see it. And I think that I could not help but have a radical vision of society, and that the way I see things can help people see what needs to be changed.

What about your childhood? What particular experiences do you think caused you to become a writer?

I think isolation at an early age — a feeling of being very different from my brothers and sisters. Though I had lots of brothers and sisters — five brothers and two sisters — I was the youngest and felt very lonely. They seemed much more boisterous and much more in the, sort of, real world. And I was a dreamer. I wanted to play the piano, and I wanted to draw. But it was easier to write, so I did.

I grew up in a farming family, tenant farmers, sharecroppers and dairy people. My mother and father both worked in the fields and both milked the cows. My mother, of course, carried forth the whole family tradition — making clothing, tending the house and the garden and all the things that women traditionally do. We always lived in the country and that turned out to be really a wonderful thing. The houses were awful, but the beauty of the country was so fine.

In 1976, in Ms. magazine, you wrote that you have no doubts about being a writer, but you have always had doubts about making a living by writing. How difficult, as a black woman from the South, has it been for you to become a writer and to earn your living as a writer?

I really didn’t have great difficulty, as difficulties go, becoming a writer or publishing. I went to Spelman College for two years and then I went to Sarah Lawrence, where I had a very fine teacher, the poet Muriel Rukeyser, who recently died. I wrote some poems, really because I was having various kinds of difficulties and I simply wanted to make it through the night and the next night and the week, if possible. So, I wrote poems that seemed to come out of that feeling. I had just come back from Africa, so the poems were full of African images, and I had also just been working on voter registration in Liberty County, Georgia, so the poems were full of that, too. In any case, I put these poems under her door — she had a little cottage in the middle of the campus, and then I more or less forgot about them. But she gave them to her agent, who gave them to Hiram Hayden, who was an editor at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, and he took them, and then Harcourt Brace published my next five books.

So I didn’t have any difficulty publishing. The difficulty comes from a lack of distribution from major publishing companies. I’ve had to really struggle with them to make them distribute my books. And then the payment is really very small, especially in the beginning. For my first book, the advance was $250. You really cannot live on $250 for very long, so I had to do other jobs. For instance, I worked for the welfare department in New York, and I taught, and I did various things to earn the money that permitted me to write. And it’s only been in the last five or six years that I’ve earned my living completely by writing. Just to have something published is wonderful, but it is not the end of it by any means. You really need to be able to support yourself.

Do you think you have been somewhat ignored, as a lot of black men and women have been ignored, by the literary establishment?

Well, I suppose you could say that. Except in my case, I have not been ignored by the people who matter to me. I have always had wonderful responses from women, black women and white women, and other third world women. I have not really cared even to be reviewed by certain white male literary persons who I would imagine, and do in fact, control the literary scene. I’ve felt very good, actually, about my rapport with my audience.

I always wanted to be an honest writer. I always wanted to be an honest person, and I think that whatever I write comes out of that. So, if I sit down to write about my experience, I try very hard not to censor myself, which most women do, because they really are still concerned about what people will think.

I don’t know if I can explain how things can be autobiographical without having happened to me. . . . It’s just that they exist in my consciousness. For instance, the first short story that I wrote and published, in 1967, is a story called “To Hell With Dying,” and it’s about an old man, Mr. Sweet, who dies. There was a man named Mr. Sweet, but then nothing else happened. You know, it’s autobiographical only in the sense that he existed, but then the rest is imaginary.

The poems in Good Night Willie Lee were deliberately published even though they are very personal, because I wanted to publish the poems that I feel most women never publish, the poems when they talk about failed love affairs, and a sort of cynicism, and a rage about a relationship. Those are personal poems, but once having published them, actually once having written them, they no longer strike me as being particularly personal, because I know that they apply to other women, just as well as they do to me. So that, when I read these poems, women respond as if they wrote them themselves, and actually that’s exactly what I wanted to accomplish.

And you weren’t concerned at all that millions of people around America might be reading about a failed love affair of yours?

But they have failed love affairs, too. And I think if they can see that you can live beyond having failed anything, then they would feel a lot better. The tendency has been, in earlier women’s poetry, to write as if, when something fails, you just crawl into your little corner and die. Well, that’s ridiculous. When you fail at something, you hop up and get in your car or get on your bicycle and you move right along. That’s life.

Do you think that there is a body of literature called women’s literature that is unique?

Oh yes, I do. I think that is because women really do see the world differently from men.

You write very much as a Southerner. Beyond just giving a backdrop for your stories, how has the South affected your writing?

Well, the first thing that comes to mind is really landscape. I think that if I had been brought up in New York City, I would not write stories with the land so much a part of them — trees being so big, and silence being so necessary, and birds being so present. I think, of course, that growing up in the South, I have a very keen sense of injustice — a very prompt response to it. And I think that is in my writing and in the things that concern me.

You’ve written some about why you stayed in the South to write during the Civil Rights Movement.

Well, I didn’t think I could have been accurate to the events of the Movement if I had lived in New York, where I was living right after I graduated from college. But to really write well about the spirit of the Movement, which was what was of interest to me, I had to be there. I had to be not only in the South but in Mississippi. It seemed to me to be the heart of the spirit. That is why Meridian is such a strange book. I think people think of it as slightly weird, or very weird. But it is, I believe, very, very accurate in terms of capturing the spirit and the spirits of the people who made the Civil Rights Movement.

Do you think people think that Meridian is weird because of the mysticism and the spirituality, almost, of the main character, Meridian?

People who have an extreme sense of responsibility and a very deep awareness of injustice, people who really suffer, because things are not right, are perceived by many people as being deranged. This means that most of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement were deranged people, in the minds of people outside of the South who were not really aware of the kinds of character that we saw during the ’60s.

How much is Meridian you?

Well, people always ask that, and it is very hard to answer. If you’re talking about the spirit, then she would be a lot like me, I think, but her life is really quite different, and her circumstances, too. Whereas she was pregnant at 17 and gave up her child, I was living in Jackson and had my own child and was married to an attorney. So the circumstances were different, but I think there’s a lot of the same spirit.

I now live in San Francisco, and it’s very different from the South, and yet in terms of beauty, there are certain similarities. I went down to visit my mother this weekend [in Eatonton] and I made a wrong turn off the highway and went down a road in Monticello that I had never seen before. It was just strikingly beautiful. In California there is a similar kind of just wonderful, beautiful landscape. The difference is probably that I feel more free in California than I’ve ever felt anywhere.

People say that there is a lot of violence in all Southern literature, and there is some in your writing, also. Can you speculate on why we have so much violence both in our Southern culture and, I think, in our writing?

I think we basically write what we see, and if there’s violence to be seen, it’s violence that we write. And I really become annoyed with people who ask the question as if the violence is created by the writer. And it’s not just in the South that there’s violence. America is really a violent country, horribly violent. The difference between television, for instance, and the Southern writer, or any writer, is probably just that we look at it from a moral point of view. You know, the TV has people shooting and chasing and killing and so forth, and it’s really to sell aspirin and clothing and cars. But when we look at it, we’re really trying to see what it’s doing to the people involved in the violence.

I don’t think the South is a more violent region. And I think if people had a deeper understanding of the rest of the country, they wouldn’t either. For instance, the Filipinos and the Japanese and other people who came to the West Coast to become migrant workers really suffered the same kinds of discrimination and brutality and hardship that people in the South have suffered. There’s a wonderful Filipino poet, Carlos Bulosan, who wrote a book called America Is in the Heart, and he talks about some of the beatings and the shootings and the killings that he saw and that he actually suffered himself as a migrant worker in this country. You think about various parts of the West and the Northwest where there were Native Americans who have been treated very violently. So it is really a violent country and it always has been. I mean, it has been since its founding as a country.

As an observer and a reporter of the Southern character, how do you see that we have changed since the height of the civil-rights days, as a region and as a people?

Well, I think it is much easier to travel about in the South without feeling terrorized, as I felt as a child. However, I think, and this is mentioned in Meridian, there’s a line in there where an old black man says to a younger black man that “I’ve seen rights come and I’ve seen em go.” There’s a way in which progress is sort of cyclical — you progress and then you sort of go back, and then you have to have a whole new struggle. I think that is what is happening now. I think that there is so much regression going on in the South, and in the rest of the country, but I suppose it’s sharper here [Atlanta] because of recent things, like the murder of these black children.

I think that psychologically black people have advanced. I don’t think we’ll ever be the way we were before the Movement. But I think that we are also very much out of work, and everything has to have an economic base. You have to be able to feed and clothe yourself and your children before you can really think clearly. And that worries me very much. But I think that we, fortunately, understand that struggle is a necessity, and that struggle is a possibility, and that, in any case, struggle is inevitable, and that we will have to continue fighting for every square inch that we get in this country.

Obviously, your writing is richer because of your active involvement in the Movement. What do you think, though, are the scars that were left behind, both personally and reflected in your writing?

A deep cynicism about the possibility of some people to change, or a deep cynicism about the possibility of us, as black people, ever changing them. And actually some of the people who won’t change in a good way are black people, too. On the other hand, and on the good hand, there is a kind of optimism that I have, based on what I saw of the courage and magnificence of people in Mississippi and in Georgia during the Civil Rights Movement. I saw that the human spirit can be so much more incredible and beautiful than most people ever dream it can be, that people who have very little, or people who have been treated abominably by society, can still do incredible things, amazing things. And not only do things, but be great human beings. And that was very nice to see. Did your involvement slow down your writing or hamper it in any way?

Well, actually, the writing had to become the involvement. I discovered that I could not really give to the Movement, or anything, all the time and energy that it would require, and that my ability really was in writing and that was what I should do. And I should stop feeling guilty about it. I used to go to demonstrations and always feel that I was not even there, in a way, that I was really just eyes viewing it. I finally realized that it was because I knew that I should be writing and so I did.

Did you have problems meshing that with your involvement and activism?

Oh yes, yes. Because when you’re very active, you can become so angry, for one thing, that you could never really write it well. The anger has to simmer down some before it can become something on the page that people can really deeply read and respond to. So now, when I think of my activism, it is really the writing that I do rather than anything else. One of the things that I’ve been doing more in San Francisco is writing about things like pornography and sado-masochism, and it is through writing about those things that I join with women who are more active, who may be demonstrating against violent pornography and sado-masochism.

I want to ask you about the creative process: what spurs you on and what dampens your creativity?

I don’t know. I think that Flannery O’Connor said once that the artist must have the habit of art, and that’s a sort of reflective state of mind. Something that you don’t really do yourself, I guess, it’s just that you’re sort of aware of things in such a way that when something good hits you, you more or less know it. I mean, if an idea comes in the course of the day, if it is a good one, you feel it, and you pursue it. But what dampens that, I don’t know, unless it is some humdrum activity, or work, or the inability to deal with an idea when it does come. There are times when I don’t write as much, but I don’t think of it as writer’s block. I think of it as a time when I probably shouldn’t be writing, and I should be doing something else. I mean, after all, writing constantly is no guarantee that you’re writing anything that anybody needs to read.

How is your writing changing over the years?

I think, believe it or not, it’s becoming even more direct. I say that because people often say, “Well, you know, you’re really very direct,” as if there should be more subtlety. But I think, as I write, I have a real consciousness of where we are as a people and as a globe in this age of nuclear action and reaction. I don’t think that there’s a whole lot of time for subtlety, when directness will serve. So I think I’m always moving toward more and more clarity and directness.

What kind of a future do you wish for your own daughter, Rebecca?

Oh, the future I wish for my daughter isn’t possible in this society, so really the most that I could wish for her is that she overcome the society in some ways, in all ways if possible. And that she manage to have a really good life and a good time, and happiness, even though this society is sick and racist and sexist, and, you know, doomed in many ways. I hope that she does not have cancer from radioactive fallout. I hope that her children are not malformed because of the pollution in the water, and in the air. I hope that she can be healthy and I hope that she can have joy. But I hope, I suppose most of all, that she will not stop struggling to have happiness and joy in her life, because she deserves both.

Tags

Krista Brewer

Krista Brewer is a free-lance writer based in Atlanta. (1983)

Krista Brewer lives in Atlanta, where she was born, and is on the staff of the Clearinghouse on Georgia Jails and Prisons. (1981)

Alice Walker

Alice Walker is a novelist and poet. (1981)