Lessons From a History of Struggle

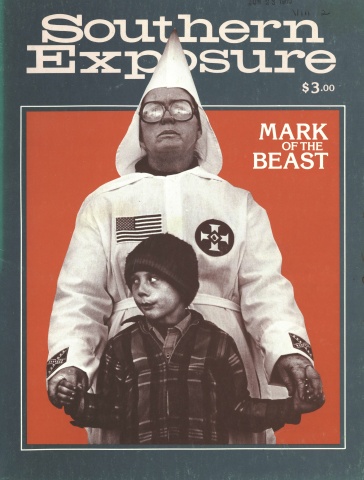

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

Recently 10,000 people, black and white, marched in Greensboro, North Carolina to say “no” to the Ku Klux Klan and racism. They came to express outrage at the massacre of five anti-Klan demonstrators by Klansmen and Nazis in Greensboro on November 3, 1979. The murders took place on the street, in broad daylight, in front of TV cameras — a new level of open racist terror in America. More and more people now recognize the Klan resurgence cannot be written off as a lunatic fringe, and that we must organize to stop it. The Greensboro demonstration was called by the National Anti-Klan Network, a coalition that emerged from meetings organized in late 1979 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization (IFCO). The coalition is attracting broad support — church groups, trade unionists, community activists, representatives of the political left. More than 300 organizations co-sponsored the Greensboro action.

If the struggle to isolate the Klan and ultimately destroy it is to succeed, we must understand the long and bloody history of the Klan; we must sift out the lessons we can learn from that history; and we must understand why it keeps reappearing in our land, like a cat with nine lives.

Next, we must analyze why there is a revival of the Klan at this particular time and the danger it represents. And we must develop an approach to fight it that goes deeper than the Klan itself.

First, the lessons of history. In the first place, each period when the Klan attempted and sometimes achieved growth was a period of economic and social turmoil. This was certainly true in the South after the Civil War, when the Klan was initially organized. That was a time of upheaval, a revolutionary time, and for a short moment a very promising time. Free slaves were literally setting up new governments in the South. And, as the history books usually overlook, at least some of the disinherited whites of the South, who never had a stake in the slave-owning society, joined with blacks to form those new governments and institute programs that met people’s needs.

But other whites were confused and feared economic competition from the freed blacks, so they joined the Klan — which was started in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1865, by the sons of the old ruling class who wanted to regain their power. With the poor as their troops, they did indeed eventually regain that power, overthrowing those new governments by force and violence. After that, the Klan disbanded — not because its ideology had been abandoned by the ruling class, but because they didn’t need it anymore. The Klan ideology simply became the prevailing force in the official governments of the South, and indeed of the country, in the following decades.

The next period when the Klan experienced great growth was the 1920s. It reached its greatest numerical strength, an estimated five million, with the ability to elect mayors, city councilmen, state legislators and members of Congress; the Klan was really running the country.

Sometimes people don’t think of the ’20s as a time of turmoil: it was also a time of repression, and by the end of the decade things were quiet. But the beginning of the decade was tumultuous: black veterans returning from World War I expecting to enjoy some of the democracy they had supposedly fought for; workers organizing unions; people afraid of depression; and on the world scene a recent major revolution, as the ruling class was ousted in Russia. The Klan presented itself as a great force for stability, attacking blacks, Jews, Catholics, Bolsheviks and finally anyone it did not consider properly moral. And it recruited many people who were confused by the uncertainty of the times.

Both these times of great Klan growth — the post-Civil War period and the 1920s — were periods when great numbers of people felt overwhelmed by problems, in their lives and society, which they saw no answers for.

On the other hand, we miss an important point if we conclude that in any period of turmoil the Klan will become strong. It’s not that simple. If that were true, the Klan would have experienced great growth in the 1930s, and it didn’t. Yet that was a period of one of the worst economic crises this country has ever known. The Klan tried to re-organize in that period, and it was very violent and dangerous. But in the 1930s, it never really recruited great numbers of people.

Again, consider the 1960s — a time of great social crisis in this country. The Klan again tried to build a mass movement. Again it was violent and dangerous, but again it never really built a mass base. Membership for that period was estimated at 20,000 to 40,000 — too many, but nothing like the millions of the ’20s. Ultimately public opinion turned so strongly against the Klan in the 1960s that some Klansmen were actually prosecuted and sent to jail.

So the second lesson we can learn from history lies in what characterized those periods when the Klan, despite great efforts, did not achieve great strength. Both the 1930s and the 1960s were times when (1) strong mass movements advocated real answers to social and economic problems, and (2) there was a strong offensive against the ideology of racism.

In the 1930s, powerful people’s movements, like the new labor unions and the unemployed councils, were preaching the necessity of black-white unity. And in the 1960s, the black freedom movement generated a moral fervor around a program of human rights. That fervor was not just mobilizing blacks; it stirred the whole country. Young white people found meaning in their lives in the fight for justice and against war; poor whites learned that they could join with blacks and fight for a better life. White Appalachians weren’t joining any Klan because they were joining the Poor People’s Campaign organized by the SCLC in Washington; and white workers organizing unions in the South were coming to civil-rights groups for help.

The third thing we notice in the patterns of history is that, although the Klan has most often drawn numerical strength from the poor, it has been encouraged, and probably financed, by those with wealth and power. This was certainly true in the early days of the Klan after the Civil War. And it was also true in the 1930s, when the Klan was not gaining many members but was viciously attacking labor unions. All of a sudden it had funds from somewhere to open a flashy Atlanta headquarters and hire a lot of organizers. Undoubtedly, the same thing is going on today.

The fourth lesson we can learn from the Klan’s history is that when an aroused citizenry forms a counterforce against it, it can be stopped. That happened even at its time of greatest strength, the 1920s. The Klan became so violent and cruel that finally decent people, white as well as black, organized and said no — and they prevailed, temporarily.

But the final lesson we must recognize is that although it has declined, the Klan has never totally disappeared. It keeps rising again, because we have not yet defeated the ideology that gives rise to it. That ideology is racism, which has poisoned the minds of the white people of this country and caused poor and working-class white people again and again to work against their own best interests.

Which brings us to the present. We see a resurgence of the Klan today because again we are in a period of social and economic turmoil. But this time it’s worse than at any other period in our history. We are living at a time when our society is really falling apart. Our economy is in deep trouble, there are not enough jobs for our young people, our cities are decaying, our school systems are deteriorating, the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer, more and more people are having to struggle just to survive. It has become quite obvious that the people who are running our society are simply not willing — and perhaps not able — to make the fundamental changes necessary to make this society function to meet the needs of its people. And if you are running a society that is not working, and you are not willing to change,you have only one other choice: you’ve got to find ways to keep people under control.

That’s why a batch of repressive laws are pending in Congress. That’s why those in power are building 500 new prison and jail units across the country, at a cost of from $35,000 to $50,000 per cell. That’s why there is a rash of new capital punishment laws on the books, and Death Rows are filling up all over the nation.

But to keep people under control, you’ve got to go further than that. You’ve got to explain to large sections of the population why they are having problems, and that explanation has to preclude their looking for and finding the real reasons. In other words, you have to create a scapegoat mentality among the majority group in the population. And if you do that successfully, you create the basis for something we’ve never had before in this country — a mass fascist movement. And once you have a mass fascist movement, you are on your way to something else we’ve never really had (except, to a certain extent, in the South before the civil-rights movement): a police state.

Because of the racism that undergirds our society, the potential scapegoat is built in: black and other minority people. If we understand all this, we understand why the Klan is growing again today. The cause of the problem is not a few criminal individuals who don sheets and hoods and set out to kill. These people are dangerous and they’ve got to be stopped. But they are an effect, not the cause. The cause of our problems lies with the people in high places who are creating a scapegoat mentality among this nation’s white people. It’s the powerful people — from the halls of Congress to the board rooms of big corporations — who are telling white people, for example, that if taxes are eating up their paychecks it’s not because of our bloated military budget but because too many government programs benefit blacks and other minorities; that young white people are unemployed because blacks are getting all the jobs; that crime in the streets is caused by black people. That message from powerful propagators is creating the climate in which the Klan grows today; that’s what is laying the basis for a mass fascist movement in the 1980s.

But that movement does not have to grow. It is fully possible instead to build in the 1980s a people’s movement that deals with real problems and has the strength to turn this country around in the next decade. But to do that, we’ve got to fight not only the Klan but the Klan mentality, the ideology that undergirds the Klan.

Let's analyze that ideology. The new Klan leaders are saying they are not racist, that they don't hate black people, that they are not against equality for all people. In fact, they say, they are for equality. But the problem, they say, is that now black people are getting everything, they’ve made “too much progress,” and now it’s white people who are discriminated against. Somebody, they say, has got to protect the rights of white people—and that’s what the Klan is for.

If you listen carefully to that argument, you realize that it’s precisely the same thing being said by all the forces advancing the concept of “reverse discrimination.” Bakke and others say it politely in academic classes and in the halls of Congress, and the Klan says it with violence in the streets — but they are saying the same thing.

If we are to defeat the Klan ideology, we’ve got to take on the whole idea of reverse discrimination and expose it for the hoax that it is. We’ve got to find the forums — and most often those arise in the context of struggle — to say to the white people of this country that the whole idea of reverse discrimination is a snare and a delusion and just a plain lie.

It’s a lie because it is based on at least two myths. The first says black people have now made “too much progress.” That’s easy to explode with a few facts and statistics, but often white people don’t have that information, and the media is not giving it to them.

For example, a few years ago, unemployment among blacks was one to one-and-a-half times as great as among whites; now it’s two to two-and-a-half times as great — the gap is getting worse. A few years ago, median family income among blacks was 62 percent of the median income for whites — bad enough. Now it’s 57 percent — the gap is getting worse. A few years ago, 25 percent of black people lived in poverty; now it’s 28 percent, and 42 percent of black children live below the poverty line. The gap between white and black infant mortality has increased since 1950. One could go on and on. Today, by official figures, unemployment among black youth is about 35 percent, and more accurate unofficial figures put the percentage at 60 to 65 percent, and in some cities 75 to 80 percent. A whole generation of black youth is being systematically destroyed. That’s not progress; it’s a national disaster.

The truth is that, because of racism, those in power have made a de facto decision: Since there does not seem to be enough for everybody (which is a myth too), black people can do without. If there aren’t enough jobs for everybody, let blacks be unemployed. If there’s not enough decent housing for everybody, blacks can live in slums. If there is not good health care for everybody, blacks can die young. This is the essence of racism — the premise that if there are problems to be borne, black people can bear them. So much for the myth of too much black progress.

The second myth that feeds the notion of reverse discrimination says whatever progress blacks have made has in some way taken something away from white people. This is simply not true. In fact, the opposite is true. Every step forward by blacks has opened up new opportunities for a better life to white people, especially poor and working white people.

Many white children, for example, do better in school today because they were able to attend Headstart programs. Twenty years ago there was no Headstart; like all the compensatory programs in education, it began because black people struggled for better education. What they won is only a pittance compared to what is needed, but in what they won whites shared. Many low-income white young people now attend college because of Basic Educational Opportunity Grants (BEOG); these grants didn’t exist until blacks struggled for educational opportunity. Many unemployed whites have found a lifeline in a CETA job; CETA, like all jobs programs, as meager as they are, happened because blacks demanded jobs. They haven’t won much, but what they won whites share. Many poor white people get help on legal problems today from public service law programs. These developed and expanded in the wake of the movement of the ’60s, which pointed up the lack of legal services available to blacks. Blacks struggle for health care, a community clinic is set up — and whites too have access to better health care. Many similar examples can be cited.

The truth is that the struggle of black people for freedom arising in the ’50s and ’60s shook up this whole society and made it possible for all people to struggle for a better life. It arose when the country was paralyzed by what we call McCarthyism and we were experiencing the Silent ’50s. It broke the pall of the ’50s; it made possible the anti-war movement of the ’60s; it made possible the new women’s movement; it opened the way for other minorities to struggle for their rights, which they are now doing; it made it possible for workers, white and black, to organize unions in the South, as they are now doing; it paved the way for the elderly of all races to struggle for a decent life, as they are now doing; it opened the way for handicapped people to demand their rights, as they are now doing. It shook the society to its very roots. And that is why those in power were so afraid of it and why they tried so hard to destroy it in the late ’60s and early ’70s. But it never took a thing away from the disadvantaged white people of America.

It has always been this way. The turmoil following the Civil War, for example, didn’t hurt poor white Southerners: it gave them free public education for the first time. It gave them, for a brief period, governments concerned with human needs. This process is built into the structure of our society. Blacks are at the base of it, because black slave labor created America’s first wealth. So it is only natural that when blacks move upward and outward everyone will move. It is as if the foundation stone of a building shifts, and the whole structure moves. And when the day comes that this society has been stretched to the point that it really has room for black people, it will be a society that has room for everybody.

This is the basic truth that explains our society; if we understand this, we understand everything and have the basic key to our problems; if we don’t understand it, we can’t understand anything and will do all the wrong things and work against our best interest. Some of us who are white have been lucky enough to learn this great truth because we were a part of the civil-rights movement or have inherited its spirit. We say to our white brothers and sisters all across this country that we as white people have been fooled for too many generations by a pack of lies; we’ve been told that we could beat an unjust system because our skin is white if we would just help keep black people down; now we are being told we can beat an unjust system if we can just keep blacks from discriminating against us. But it won’t work; it was never a moral answer and really not practical, and now it won’t work at all. The problems today are too deep-going, too basic. The only real answer for white people is to recognize that our fate and the fate of our children is totally interwoven with the fate of black people in America — and that when we fight the Klan, when we fight against racism, we are fighting for our own survival.

As we fight the Klan today, we are really fighting all the forces, all the ideas, that are giving motor power to the current right-wing drive. We hear it said often that there is a drift to the right in America. There’s no drift to the right, there’s a drive to the right — financed and organized by powerful forces. But it can only succeed by selling to this country’s white people those myths about reverse discrimination and convincing them that it is black people who are causing their problems. In short, it can only succeed on the basis of racism. Or to put it another way, it is only on the basis of racism that a mass fascist movement can be built in America.

We can thwart the rise of such a movement if enough of us who are white join with our black brothers and sisters to tell the truth to white America. What is at stake is the very soul of America — and the future of every one of us, and of our children.

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)