This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 2, "Neighbors." Find more from that issue here.

While the agricultural chemicals industry lobbied Congress last summer to water down a troublesome pesticide control law, residents of the tiny rural community of Gorgus, 325 miles away in central North Carolina's Chatham County, hid in their homes to avoid fumes from a controversial herbicide known as Agent White.

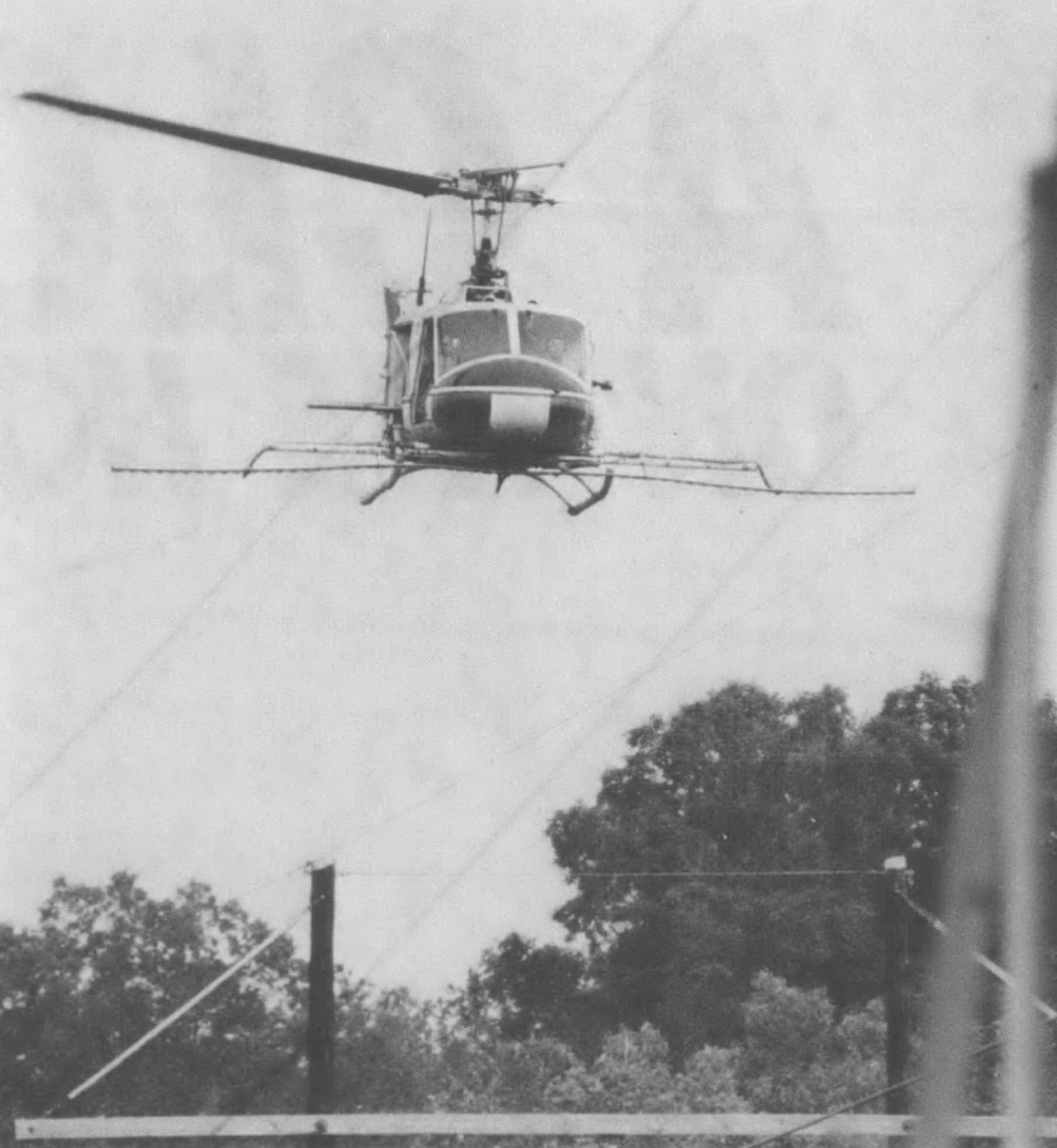

Boise Cascade had hired a specially licensed helicopter pilot from Louisiana to spray a mixture of herbicides known commercially as Tordon 101 (a Dow Chemical Company product) and Weedone (made by Union Carbide) over a 450-acre timber tract to kill off hardwood sprouts so the land could be re-planted with more marketable pine.

Investigators from the state Department of Agriculture finally determined that some of the chemical ingredients, probably 2,4-D, had volatilized — vaporized after striking the ground due to the hot, humid weather — and drifted over the adjacent, predominantly black community.

Carrie Yancey, whose land adjoins the Boise Cascade tract, was afraid to go outdoors while she nursed the youngest of her four children. She watched her vegetable gardens wither and die. There would be no produce to put up for the winter.

Billie Rogers's 12-year-old son ran into the house, coughing and eyes running, to tell his mother that a helicopter was spraying something over the area. A man on the ground told him it was safe, not to worry. But before the day was over, the Rogerses began suffering from sinus headaches, wheezing and coughing. And six months later, Mrs. Rogers said the bones in her face ached and her hands swelled up when she walked in the woods around her home.

Seventy-one-year-old herbal specialist Johnny Lee noticed brown spots on his fruit trees. Children in the community suffered stomach cramps and diarrhea, and the older residents lived in fear of it all happening again.

After learning that Tordon contains the same ingredients as the controversial Agent White — banned by the army in 1970 and thought by several respected scientific researchers to cause cancer and birth defects — Beverly Mitchell lost sleep worrying about the safety of her unborn child. "Just because it's legal, doesn't tell me it's safe," she said. Her farm had been invaded from above by the kind of chemicals she and her husband refused to use on their own garden.

Despite the 95-degree temperature and stifling humidity, most of the 10 families affected by the incident felt compelled to keep their doors and windows shut tight at night because they didn't want to breathe anything that smelled that bad while they were sleeping.

Only after the community twice requested it did state pesticide investigators consider testing affected food crops to see if they contained any traces of dangerous chemicals. A month after the spraying took place, the inspectors were unable to find any traces of herbicides in the damaged produce, but they admitted they couldn't give the food a clean bill of health since even negligible amounts might be harmful.

"If they didn't know, I sure didn't know," shrugged Mrs. Yancey, who felt it was safer to discard even the crops that appeared healthy.

Damaged Crops, But No Violation

State pesticide officials did conclude that the damage to the Yanceys' garden was caused by herbicides drifting from the Boise Cascade tract, but they declared there had been no violation of state regulations or of federal label restrictions designed to promote safe use and avoid drift.

The chemicals apparently hit their intended target, then vaporized and drifted due to an unforeseeable change in the weather, concluded John Smith, secretary of the Pesticide Board and chief investigator. The Yanceys would have to hire their own lawyer if they expected to collect any damages from the timber company or the pilot involved, Smith said.

After the Agent White cloud lifted, it was clear to this small community that neither the federal Environmental Protection Agency nor the state Department of Agriculture could protect them.

North Carolina's pesticide law, and accompanying regulations, do place some limitations on the aerial application of restricted-use herbicides like Tordon because they could pose ecological and health problems if they got into water resources and can also destroy non-target crops, like tobacco, tomatoes and other produce. Pilots must be trained and licensed by the state Department of Agriculture. No spraying is allowed within 100 feet horizontally of an occupied dwelling (except upon written permission), or 300 feet of an occupied school, hospital or nursing home. Herbicides must not be sprayed near water resources or in high velocity winds. The pilot must also follow the label instructions written under EPA guidelines — which critics say are too vague. With Tordon, the label advises that precautions be taken to avoid drift by noting the wind velocity and air temperatures.

The pesticide office of the N.C. Department of Agriculture gets about 100 complaints a year. Some of them are the result of pilot error, over-spraying and other mishaps. But many are due to the delayed drift of herbicides, which, according to the National Agricultural Aviation Association, can occur up to a day or two later in hot and humid weather. In the state of Washington, for example, 2,4-D drifting from aerial application over forest lands has been cited for extensive damages to grape crops five miles away.

Neither North Carolina nor EPA have stated in their restrictions the specific climatic conditions that could cause volatilization and drift, such as air temperature, fog banks, humidity or the likelihood of rain.

Since North Carolina's law does not require the company or pilot to notify adjacent residents in advance of spraying, they have no way of preventing the damage to themselves or their gardens. North Carolina law does require the company to notify beekeepers in advance if they have a registered apiary within a half mile of the target area, a point that beekeepers lobbied for several years ago.

"Shouldn't humans at least be considered as important as bees?" asks Billie Rogers.

Neither North Carolina nor EPA monitors aerial spraying programs to see if regulations are followed. The state will investigate only when they receive information, usually from private citizens, that leads them to believe a violation may have occurred. It took Gorgus residents many phone calls to convince state officials, who had already determined that no violation had occurred, to at least come back and test some produce samples to see if their food would be safe to eat. It was that sense of helplessness that prompted members of the community to ask local authorities to study the issue and help them make changes in the state laws and regulations.

The residents of Gorgus are not alone in their concern about herbicide drift. While the Yanceys and their neighbors wondered what they could do to prevent this from happening again, citizens in Cherokee County in western North Carolina were taking a count of increasing cancer deaths over the last five years, deaths which they believe are linked to the use of Tordon by power companies, the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture since 1966. State health officials went up to the mountainous county last summer to see if they could find any scientific evidence to support these claims.

Meanwhile, North Carolina's Senator Jesse Helms was up in Washington, trying to make life easier and more profitable for Dow Chemical Company and other major agricultural chemical producers by drafting a Senate bill that would significantly limit the public's knowledge of potential health hazards associated with herbicides and the ability of states to pass regulations that exceeded federal controls. Thanks to Helms being tied up in the Christmas, 1982, filibuster against the gasoline tax, that bill (a revision of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act — FIFRA) never made it out of his Agriculture Committee, but it is expected to spark a battle between an environmental-consumer-farmworker coalition and the pesticide industry in this session.

Frustrated by the decline in the Reagan administration's EPA and worried about efforts in Congress to weaken FIFRA, citizens across the U.S. have turned instead to their state courts, legislatures and regulatory agencies for protection from herbicide drift.

Complaints from Gorgus prompted other Chatham County residents living adjacent to the 23,000 acres of commercially owned timberland in the county to join forces to change the state law governing the aerial application of herbicides. They have asked their county commissioners and planning board to study the issue and help them request changes from the state pesticide board and the state legislature.

North Carolinians stand to learn from the experiences of those involved in similar situations in other states, most notably West Virginia, where citizens' complaints about herbicide drift prompted an investigation by the state's Attorney General, a state Supreme Court ruling about spraying, and the eventual enactment of strict controls.

Banned in Vietnam, Hailed at Home

Although phenoxy herbicides like Tordon have been widely used across the U.S. since the 1960s, complaints from rural residents have grown over the last four or five years as information about the potential health hazards associated with their use have been publicized.

Suggestions that phenoxy herbicides might be harmful to human health come in part from Vietnam veterans, who have filed a barrage of lawsuits against the federal government claiming that exposure to the defoliant Agent Orange (a mixture of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T) caused cancer and other health problems. (See Southern Exposure, Vol. X, No. 2.) Agent White — a mixture of Picloram and 2,4-D (now marketed commercially as Tordon) was widely used in Vietnam as a defoliant along with Agent Orange. The U.S. Army stopped using Agent White in 1970, after a study concluded that, of the four commonly used military herbicides, Picloram posed the greatest potential for causing "long-term, permanent ecological damage."

In 1973 the National Academy of Sciences interviewed more than 30 Montagnard tribe members in South Vietnam's highlands, where Agent White's use was heaviest. The subjects consistently referred to illnesses occurring among those in or near the sprayed areas, with the most common symptoms reported including abdominal pains, diarrhea with vomiting, respiratory symptoms and rashes. Some noted an unusually high number of deaths, particularly among children, following the spraying.

Despite the army and NAS studies, timber companies, the U.S. Forest Service, power companies, state transportation departments and the USDA continued to use considerable quantities of Picloram, 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T to kill off persistent woody growths. When EPA suspended the use of 2,4,5-T in 1979 after it was linked to miscarriages in Oregon, the use of 2,4-D and Picloram increased in its place.

The chemical 2,4-D, registered for use in the U.S. since 1948, is one of the most widely used herbicides today. About 1,500 products registered with EPA contain the ingredient, and more than 70 million pounds of it are distributed annually in the U.S. Picloram, registered in 1963, is one of the four major products in Dow's agricultural chemicals division, and earned the company more than $500 million last year.

The chemical 2,4-D is used in Weedone, and together 2,4-D and Picloram are known commercially as Tordon or Amdon, products which are sprayed from helicopters and planes over public and private forests and utility company rights-of-way. According to a 1979 study conducted for EPA by a California consulting firm, nearly 700,000 pounds of Tordon have been used on 135,000 acres throughout the Southeast, mostly by power companies.

The U.S. Forest Service used 49,000 pounds of Picloram on 77,000 acres of national forests, much of it in the South. The Forest Service uses a quarter ton of Tordon a year on 800 acres of clear-cuts in the Nantahala Forest in Cherokee County alone. The USDA's Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service subsidized the use of Tordon pellets by western North Carolina farmers to eradicate the persistent multiflora rose. The plant, which the government had introduced in the South in the '40s to control erosion, had gotten out of hand.

Boise Cascade representative Charles Sibley told the Chatham County planning board that his company viewed the Gorgus spraying as a successful experiment. Now that they have gained experience, they plan to do more spraying in the future, he said. Boise owns about 9,000 acres of land in Chatham County alone.

The Data Gap

Although both Picloram and 2,4-D are registered for use by EPA, the agency does not have in its files the studies conducted by the army or the National Academy of Sciences. In justifying the continued use of the herbicides, EPA relied solely on animal tests conducted by private laboratories under contract to Dow and the National Cancer Institute.

The first two tests were conducted in the late 1960s by Industrial Biotest Laboratories of Northbrook, Illinois, the largest chemical testing lab in the U.S. The lab was later charged with falsifying the data and fabricating the results, and the tests were thrown out as invalid. The third test, conducted in 1977 by Gulf Research Institute in New Iberia, Louisiana, for the National Cancer Institute, has been criticized as deficient. Analyses of these tests have caused a schism in the scientific community between those who believe they show Picloram is carcinogenic and those who do not.

In 1979, Dr. Melvin Reuber, then a noted pathologist with the Frederick Cancer Research Center in Maryland, reviewed evidence prepared by Dow and Gulf and said, "There's no doubt in my mind that Picloram is a carcinogen."

But EPA based its conclusion on the consensus of the NCI review committee, which held that the presence of benign tumors does not necessarily mean a substance will cause cancer. EPA admitted that more data is needed on the long-term effects, but in the interim maintains the position that no current evidence exists that Picloram poses risks of "unreasonable adverse effects to human health or environment."

Herbicide proponents from the timber, agricultural and pesticide industries say if it's okay with EPA, it must be safe.

Charles Sibley, who was in the helicopter that sprayed Tordon over Gorgus, said he had gotten the stuff all over him and never experienced ill effects. He said he has several children and had another one on the way at the time and he was not worried about long-term effects. "If we didn't think it was safe, we wouldn't use it," he said. "We want to be good neighbors."

Dow research scientist Wendell Mullison insists that Picloram is "completely safe for humans." He said table salt is three times as toxic.

Rick Hamilton, a pesticide specialist at North Carolina State University, told a group of concerned Chatham County citizens that the controversy over Agent Orange and Agent White stemmed from "emotional environmentalists" and a "media blitz." He said that most people who complained about damages were "publicity hounds." "I would have no qualms about my children being sprayed," he said. "I've been covered myself."

Before coming to N.C. State five years ago, Hamilton worked for the forest industry for a year in Virginia, where he was involved with spraying 2,4,5-T. He said he believes both Agent Orange and Agent White are safe.

West Virginia's Experience

The fact that non-target crops have been damaged by drifting herbicides, and people have experienced a variety of short- and long-term ill effects, leads many to believe EPA's label restrictions are not enough to protect the public.

Many states, like North Carolina, have regulations that essentially echo EPA guidelines on the use of herbicides, but they do not resolve the problem of volatilization and aerial drift. West Virginia was in that boat in May, 1980, when Bob Welsh was arrested for shooting at a helicopter spraying 2,4-D over a utility company right-of-way on his land, high atop Egypt's Ridge in Roane County. The judge understood Welsh's concern and acquitted him on self-defense. "Any reasonable person could have felt threatened," the judge said.

Welsh went on to become somewhat of a folk hero, and West Virginia went on to become the first state to really restrict the aerial application of herbicides.

Citizen concern about the aerial spraying of herbicides in West Virginia began as far back as 1977 when 2,4,5-T was still being sprayed by power companies over private rights-of-way. Steve White and Carol Sharlip had just moved from Baltimore to a 100-acre farm on a hillside in Chloe in Clay County, where they planted a large organic garden. They became concerned when they found out the power company was spraying 2,4,5-T from a truck onto the right-of-way behind an occupied trailer at the corner of their property.

They joined their neighbors in the West Virginia Citizens Against Toxic Sprays, patterned after a similar group in Oregon. The Oregon effort eventually prompted studies on the relationship between the use of 2,4,5-T by the U.S. Forest Service and timber companies and the prevalence of miscarriages in one area of Oregon.

White and Sharlip were relieved when the use of 2,4,5-T was banned by EPA, but disappointed when they saw a power company helicopter return in the summer of 1980 to spray Weedone (2,4-D) and Picloram over the same area.

After hearing about Welsh taking a shot at a helicopter in neighboring Roane County, Sharlip, White and their neighbors marched down to the regional office of Monongahela Power Company to let them know they weren't too happy about what was happening in their community either. The Citizens Against Toxic Sprays set up a hot line, establishing three local telephone numbers that citizens could call in the northern, central and southern parts of the state to report and describe the effects of herbicide spraying in their communities.

"We got 60 calls alone in our area," White said. "They got even more up north."

The state Department of Agriculture investigated several incidents and soon concluded they involved violations of federal law.

"EPA didn't seem interested in prosecuting," White recalled. "I think they were afraid that their labels were too vague and might not hold up in court. It was then that state officials realized the need to write stronger regulations."

After the hot line was established, one irate citizen called the attorney general's office immediately after his land was sprayed. The attorney general assigned deputy assistant Dennis Abrams, head of a special environmental task force, to investigate.

"He was extremely interested in the issue," White said. "It was the additional pressure from the attorney general that got things moving over at the Department of Agriculture."

Abrams was concerned when his office got 10 or 15 additional calls in a three-hour period. "Citizen concern had been building over the last few years," he said. "But that summer (1980) it was humid and unusually hot, and the power companies did a lot more spraying than usual. They sprayed right on the ridge top in Roane County, and a heat inversion kept everything close to the ground. There was a tremendous amount of drift." Although only one or two people said they were directly sprayed, many complained of headaches and nausea.

Abrams called in health, water resources and agriculture officials to conduct soil, water and crop tests. "Things just mushroomed from there," he said. "Another incident occurred a week or two later and we heard the same complaints and symptoms. Suddenly people came out of the woodwork to report prior incidents."

Among the prior cases were those cited in a petition filed by a group of citizens before the state Public Service Commission, complaining that several power companies were responsible for dangerous spraying incidents occurring from 1977 to 1979. Citizens asked the PSC to enact regulations that would demand: prior notification of residents on land adjacent to rights-of-way; wider buffer zones around homes, animals and water resources; and a commitment that the utility company would not spray if the landowner volunteered to clear the land by hand or machine — without herbicides.

While the PSC was hearing that case, the attorney general's investigation was showing results. The power companies agreed, with pressure from the attorney general, to a moratorium on further spraying until the investigation was completed. Meanwhile the attorney general set up a task force of citizens, health, water and agriculture officials and power company representatives to draft some guidelines for the agriculture department.

Shortly after the guidelines came out and the power companies agreed to abide by them, the PSC made a ruling on the citizen petition and asked for similar restrictions against aerial spraying. "The PSC ruling added clout to the agriculture department's new guidelines," White said. "At that point the power companies had no choice but to go along."

Eventually the state of West Virginia enacted those guidelines as law. Under the new regulations, a power company wishing to spray a right-of-way must provide written notification to the pesticide section of the state Department of Agriculture, local radio and TV stations, at least one local newspaper of general circulation, all adjacent property owners and tenants or others in control of land next to the right-of-way who have made a written request. The notice must describe what herbicides will be used, and where, when and how they will be applied.

What makes West Virginia's law unique among other states that have passed similar restrictions are two sections: one addressing volatility and drift, and the other requiring the power companies to give residents the option of maintaining the right-of- way themselves.

Under West Virginia law herbicides cannot be sprayed from a plane or helicopter when the wind velocity exceeds five miles per hour, when the spray may come into contact with a fog bank, when temperature inversion and air stagnation are present, when the air temperature exceeds 90 degrees Fahrenheit, or when it is raining or apparent it will rain within two hours. Without these specific conditions, judgment about the likelihood of volatilization and drift would be left entirely up to the pilot.

The law also gives the landowners the right to clear the right-of-way on their own land, forbidding any application of herbicides, and the state is now encouraging citizens to negotiate with power companies for reimbursement for any work they do for them on the right-of-way. "This was a very essential provision for those people who are adamantly opposed to the use of herbicides. It gives them some measure of control over their own land," White said.

A year after West Virginia enacted these provisions, the state Supreme Court added teeth to them by ruling that old right-of-way agreements between property owners and the power company never gave the utility the right to spray herbicides over the land in the first place. The court declared, "It was clearly not the intent of the parties to allow the power company to destroy all living vegetation within the area sprayed or adjoining areas where those deadly herbicides could drift."

"Our organization always contended that the landowner should control what happened to his land," said White. "The state Supreme Court decision was the ultimate affirmation of our position. A lot of utility companies think there are good reasons for spraying along their rights-of-way and that there are some times when it is the only way to go," White said. "But this decision tells them they can't do it just because they have a right-of-way agreement."

Both Abrams and the Citizens Against Toxic Sprays are pleased with the outcome of their efforts. There was virtually no spraying at the end of 1980 and only one or two complaints during the summer of 1981. Sharlip believes that the actions of Agriculture Commissioner Gus Douglas, the pressure from deputy attorney general Dennis Abrams, and the state Supreme Court ruling now mean that the spraying problem may be over in West Virginia.

"We're waiting to see what will happen next summer," she said. "But I feel that, because of the concerns raised by citizens, state officials and the courts, the power companies have decided not to spray anymore."

White said the key to the success of their campaign was not putting all of their eggs in one basket. "We couldn't just stop with the agriculture department," he said. "And I would caution citizens in similar situations in other states not to simply pick the most obvious channel for applying pressure. Departments of agriculture tend to be in a funny position because most of their responsibility lies in the area of encouraging herbicide use. They tend to get behind it and look with suspicion on citizens who criticize that approach."

Both White and Sharlip said that Agriculture Commissioner Douglas responded with concern to their complaints. But they believe that it was the additional pressure from the attorney general's office and the rulings from the state Supreme Court and Public Service Commission that combined to make it very difficult for the power companies to refuse to cooperate.

West Virginia's regulations are considered by some to be the best in the nation, and several other states are now fashioning new regulations from the West Virginia model. Connecticut and Wisconsin recently enacted stiffer aerial spray regulations calling for advance notice and buffer zones, and TVA has taken a second look at when and how to apply herbicides aerially. TVA requires advance notice to all adjacent landowners or residents and has made it a policy not to spray when a feasible alternative exists.

What About Long-Term Effects?

Some critics of the use of aerial application of herbicides like Tordon think that advance notification and wider buffer zones are not enough. "That's just window dressing," said Colin Ingram, a freelance writer in the Hanging Dog community in western North Carolina.

Ingram, who has counted 158 cancer deaths in his area between 1977 and 1981, believes they may be tied to the use of Tordon over the last 17 years. He thinks that the state should also be looking at health and safety data on these herbicides before allowing their use — reliable data that was not contested or thrown out for being falsified.

Jay Feldman of the National Coalition Against the Misuse of Pesticides (NCAMP) in Washington, DC, agrees. Feldman has been watching the agricultural chemicals industry try to remove from FIFRA (the only federal law controlling pesticides) provisions which give states authority to pass stricter pesticide controls and give the public the right to know more about potential health effects.

"Weaker legislation and regulation at the federal level mean more highly toxic products in the air with less information on their health and environmental effects," Feldman said. He urges citizens who are studying new pesticide control proposals to also demand more health and safety data, as California already does.

Ralph Lightstone of California Rural Legal Assistance Migrant Program believes strong state controls are needed in the light of a trend toward deregulation in the Reagan administration. "EPA is now considering weakening its data requirements and dropping any efficiency requirements," he said. "Companies will be able to market a product that could be hazardous, as they already have, and not even have to demonstrate that it's effective."

The fact that EPA ignored both the army and NAS studies on Agent White and chose to stick with the Gulf study despite its deficiencies has made some critics suspicious of EPA's ability or intent to regulate the pesticide industry. "Right now the only legal handle is what's on the label," Feldman said. "Due to the lax nature of enforcement on the federal level, and the fact that many of the label instructions are based on little or bad data, there is a need for states to do something more."

The agricultural chemicals industry has been trying to restrict states' authority and the public's access to data about the chemicals in their lives ever since California passed the toughest registration procedures in the country three years ago. The major difference between California's registration procedures and those used by EPA under FIFRA are California's requirements for data on health and environmental effects. Since January, 1980, the state's pesticides law has read, "No more pesticides will be registered for use in this state unless the pesticide has been tested for birth defects, cancer or genetic mutations, or the pesticide company is undertaking such tests."

California's law angered the agricultural chemicals industry so much that they've sued the state several times, but so far they've lost; now they're trying to amend FIFRA so that states like California can no longer have standards which are stricter than EPA's. Senator Jesse Helms, chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee, has vowed to help the industry with their fight, despite the fears of increasing numbers of his constituents back home in North Carolina that the use of pesticides may have some connection with increases in cancer, birth defects and other illnesses in their communities.

Herbicides and Cancer

Tordon was introduced in Cherokee County in western North Carolina back in 1965. Since then TVA, the U.S. Forest Service and timber companies have been applying it on rights-of-way and public and private forests.

In 1976, Cherokee County still had one of the lowest cancer mortality rates in the state, with 27 cancer deaths out of 161 total deaths. But by 1979 — 15 years after Tordon was introduced and about the time it takes for cancer to show up in humans exposed to dangerous chemicals — with 45 cancer deaths out of 174 total deaths, Cherokee County had the fourth highest cancer-death rate of any county in the state. By 1981, the state's figures showed a reduction back to 34 cancer deaths out of 160. But Cherokee County residents were taking their own count.

Frank Rose, a funeral home director in Murphy, believes the government's cancer death figures are low because cancer is not always reported as the cause of death when cancer patients die of other complications. Last June he began questioning his customers and found that of the last 100 funerals at his establishment, 28 deaths were due to cancer.

When a March, 1982, article in Inquiry magazine by South Carolina writer Keith Schneider publicized the fears of Cherokee County residents, the state Division of Health Services sent Dr. Greg Smith, a physician and epidemiologist, to the mountains to investigate. Although his study is not complete yet, Smith has drawn some conclusions about the dangers associated with the aerial application of herbicides.

"There is a large usage of herbicides going on with very little information provided to the user," Smith told concerned citizens in Chatham County. "It's on the product, but the user may not be paying attention. The potential of exposure is particularly high for those living near aerial spraying."

Smith said that North Carolina's regulation requiring a 100-foot buffer zone from occupied dwellings was not enough to protect residents from aerial drift and potential health hazards. "What we thought to be safe years ago, we no longer do," he said, referring to the use of Agent Orange, which has been linked to cancer and spontaneous abortions.

Both Smith and his colleague Dr. Carl Shy, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina School of Public Health, agreed that the government approved substances like Agent Orange too quickly. Now, they say, they are suspicious about other pesticides that have been given similar government approval.

Since coming to UNC in 1973, Shy has been studying the effects of herbicides on rural counties in seven southeastern states: North and South Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana. After characterizing counties according to degree of pesticide use, Shy found an association between the intensive use of pesticides and cancer — lung cancer in particular.

"This could not be explained away by chance," he said. "There was a statistically significant relation between herbicides, pesticides and cancer." He emphasized the "subtle, delayed effects" which are not detected for 15 to 25 years. "Even if they are approved by the government, they are not necessarily safe," Shy said. "That only means they have passed toxicity tests showing they won't kill rats at certain levels. There's a great deal we don't know about them."

Caution is needed with their use, much more so than the producers would have us believe," Shy said. "These are dangerous health hazards we should stay away from unless absolutely necessary."

Pesticide producers disagree. "The public should be completely assured and not concerned if they have an accidental exposure to 2,4-D," reads a Dow Chemical Company publication. "The evidence clearly shows that such exposure would not be harmful."

Dr. Ruth Shearer, a genetic toxicology consultant for the Issaquah (Washington) Health Research Institute, disagrees. She studied the short- and long-term health effects linked to both 2,4-D and Picloram, and testified in a number of court cases involving herbicide spraying incidents. After six years of intense study of the regulations placed on chemicals which cause cancer and birth defects, Dr. Shearer said, "I have become aware of the shocking failure of the EPA to protect the public from untested toxic pesticides."

She has studied more than 30 cases of 2,4-D poisoning and more than 15 involving Picloram. All of them included the same kinds of symptoms reported in the NAS study of Vietnamese tribes sprayed with Agent White, symptoms which are not detectable in laboratory rodents.

"I don't think people should have to be exposed to Picloram," she said. "I don't think it should be used. Registration with EPA doesn't mean it's even been tested properly and it certainly doesn't mean it's safe."

Dr. Greg Smith agrees with Shearer that there is not enough data on Picloram to warrant its widespread use. "As a physician I feel that the number of studies on Picloram are very limited in number, compared to the number of studies usually required for approval by EPA," Smith says. "The data is not there to say if Picloram is safe over the long term or not."

Who's Guarding Our Health?

The realization that neither EPA nor North Carolina's Department of Agriculture did anything to prevent a potentially dangerous herbicide from drifting over the Gorgus community prompted one resident to question just who in the state should be responsible for safeguarding the health of citizens who could be exposed.

"The Department of Agriculture helps and trains farmers to use herbicides and yet they are the ones who are also called on to monitor their misuse," said Margaret Pollard, a Gorgus resident who complained to the Chatham County Planning Board.

"It seems to me that puts the fox in bed with the chickens," she said. "It's a serious conflict of interest. Their staff [Agriculture Department] came out to our neighborhood with the company [Boise Cascade] and insisted there were no toxic side effects from these chemicals. Usually when you think of monitoring for health effects, you think of health departments. I wonder if the state legislature could address putting the responsibility where the competence lies."

While the Chatham County Planning Board and local citizens continue to draft their proposals for stricter controls on the aerial application of herbicides like Tordon, residents of the Gorgus community wonder if things will ever be like they were before the spraying.

Six months after the spraying took place, Billie Rogers went out to pick wild greens and became ill. "The bones in my face ached and my hands began to swell," she said. "I went to the clinic and they said I was probably having a reaction to the spraying."

And Johnny Lee is hesitating before he goes down to the banks of the Deep River to pick wild sassafras for tea. like his neighbor Beverly Mitchell, he's a purist about the food he grows and eats.

Now he's afraid that the tea he once drank to feel better might just make him sick.

Tags

Dee Reid

Dee Reid is a journalist living near Pittsboro who frequently writes about rural and environmental issues. A former reporter and managing editor for The Chatham County Herald, she has received six North Carolina Press Association awards in the past four years. (1983)