This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 3, "Painting South." Find more from that issue here.

A bitter and violent strike by black New Orleans insurance workers in the autumn of 1940 produced a militant new generation of leaders and opened the floodgates for further labor organizing in the city. Most importantly, the strike laid the foundation for the rise of the People's Defense League, a group that author David W. Friedrichs calls "The oldest Negro voters league in the city and the 'daddy' of all significant post-World War II voters leagues to follow."

By the time the insurance strike was over, it had also propelled one man, Ernest J. Wright, into the forefront of black activism in New Orleans as a fearless and able mover of people. The story of Wright's ascent as a powerful leader parallels the victorious struggles of blacks and labor in which he participated.

In the summer of 1939, Ernest Wright accepted a position with The New Orleans Louisiana Weekly newspaper as coordinator of its recently launched Community Responsibility Program. The project aimed to present black people with a "clear picture of the conditions under which they lived and what they might do to improve them." These conditions were grim and worsening.

At this time the New Deal's Works Progress Administration was drawing to a close, and blacks across the country faced increasing unemployment and a segregated job market. Despite the labor shortage created by the booming pre-World War II weapons industries, 90 percent of the defense industry contractors refused to hire Afro-Americans. And the problems of housing and unemployment endured by blacks in the urban North were worse in the South where racism was more blatant.

As a result, the late '30s and early '40s marked a resurgence in struggles to place equal rights for blacks on the national agenda. Labor leader Asa Philip Randolph's threat of a massive march on Washington in the spring of 1941 influenced President Franklin Roosevelt to form the Fair Employment Practices Commission, which forbade discrimination in defense-related industries. With Wright as its vice-president, the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) launched a drive to enlist 20,000 youths in a 15-state voter registration campaign to bring "Full Citizenship Rights to All."

The New Orleans black community felt the pull of this national movement. Randolph's Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters held its 1940 convention at the city's Municipal Auditorium, and a local SNYC chapter produced a play, Don't You Want to Be Free.

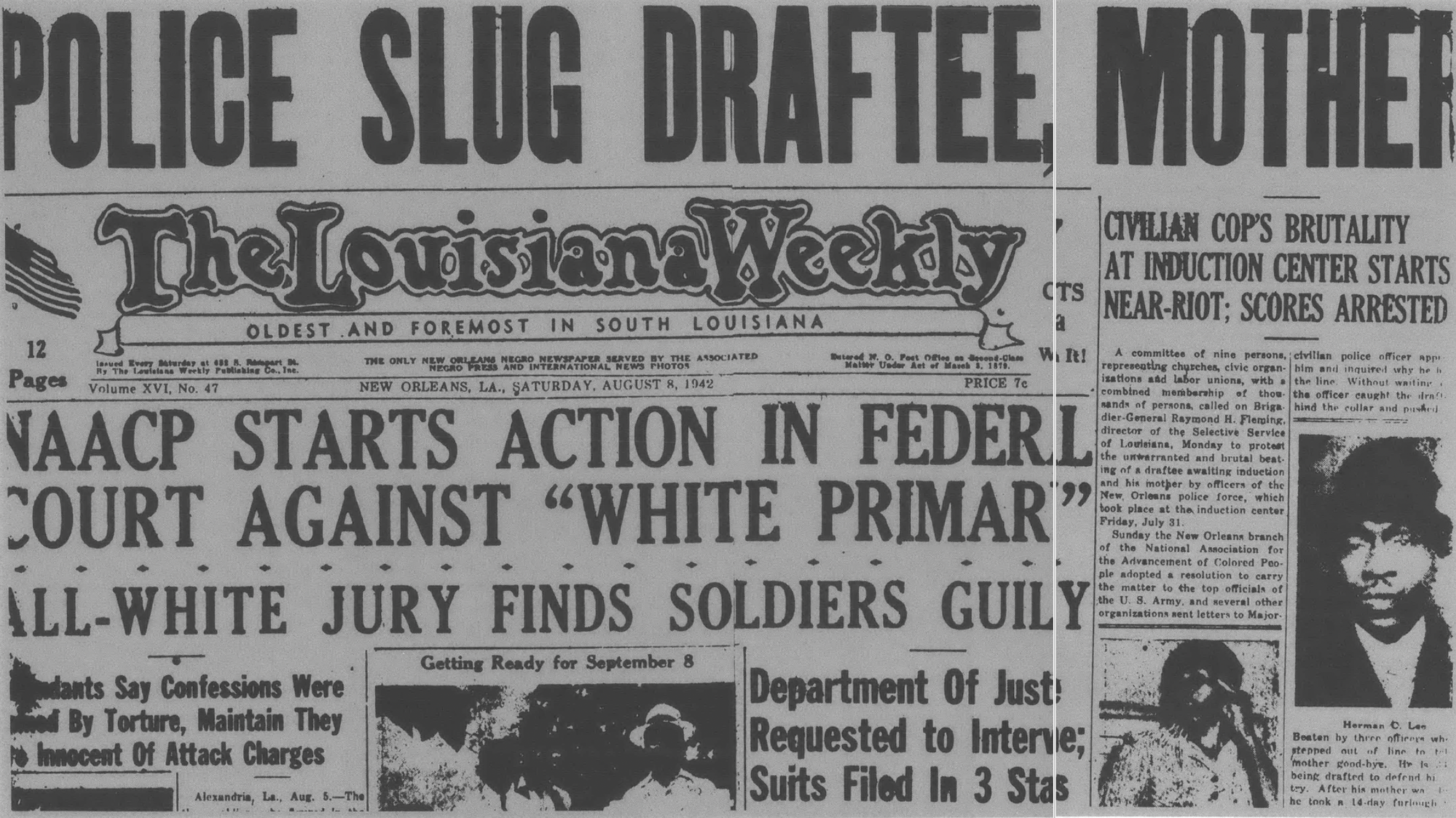

When the Louisiana Weekly initiated its Community Responsibility Program, the city "Old Regulars" of the Democratic organization, a fierce political machine, dominated state and local government. Robert Maestri was the power in City Hall, and Jim Crow was his right-hand man. Only 400 black names could be found on the voter registration rolls, black teachers were paid less than whites, and trade schools which trained youths for industry were open only to whites. Police violence was rampant and the Weekly's front page regularly featured horror stories of police terror in the city's black neighborhoods.

Already a highly respected civic leader, Wright was no stranger to the community when he took over the series of forums that were the cornerstone of the Community Responsibility Program. He was the first black social worker hired by the city and he had chaired the board of the Sylvania Williams Community Center, a recreational and social club for uptown youths. Wright received his training at New Orleans's Xavier University where he was widely known for his athletic and scholarly prowess. Later, he received a scholarship to the University of Michigan to study public administration.

Wright's experience in social work contributed to the success of the forums. In addition to being an eloquent speaker, he was adept at counseling people on their day-to-day problems. The Weekly reported sharp increases in attendance at the forums after Wright assumed control. Every week in churches, community centers, and labor halls throughout the city, hundreds turned out as he spoke on the need to obtain the ballot, reviewed the latest local and national developments, and answered their many questions. One Sunday, Wright strolled into Shakespeare Park with a loudspeaker and began what was to become a regular Sunday affair. In the years to come, thousands crowded the park to hear Wright fill the air with electrifying orations.

The 1940 strike which propelled Wright further into prominence pit the four largest New Orleans black insurance companies against their agents who sought more pay and better working conditions. When talks proved futile, the agents contacted Wright, who then organized a branch of the United Office and Professional Workers-CIO as one of the first white-collar locals in the South. The company owners, led by Dr. Rivers Frederick, responded by stating flatly that they would never negotiate with the CIO. The agents struck.

The conflict snowballed into a citywide battle for public support. The owners employed sound trucks, leaflets, and newspapers to discredit the strikers, Wright, and the CIO, while the agents appeared on Wright's Sunday platform in Shakespeare Park to explain their position. One Sunday, insurance agent Daniel Byrd produced a copy of a longstanding agreement among the four companies to keep salaries low. Byrd told the rally, "The companies found it necessary to organize, as they put it, for self-protection. How much more necessary it is that the agents organize." Willie Dorsey, the CIO's first black representative in the city, pledged the support of all the regional workers affiliated with his union, and Wright and others canvassed the black community in an effort to strengthen grassroots support.

As company income from policy collections fell, Frederick and his cohorts brought in agents from other parts of the state, equipped them with pistols, and ordered them to work the struck routes. In a countermove, the strikers accepted the expertise of two seamen, a former prizefighter called "Battling Siki," and dockworker "Poydras Street Black." The two belonged to the National Maritime Union, whose members shared a meeting hall on Decatur Street with the striking agents. The seamen scoffed at the ability of the college-educated insurance workers to deal with the strikebreakers, and they convinced the strikers of the need to take direct action against them. And they asked to be taken to the collection routes where the strikebreakers were working. By that evening, the scabs had been sufficiently discouraged from continuing their work by "Siki's" and "Poydras Street's" actions, and the companies were eventually forced to settle.

The next year, however, "Siki" and Poydras Street, along with Wright and Zachary Taylor Ramsey, the first president of Local 101 of the Insurance Guild, were taken to court on various assault charges stemming from the strike. Although Wright and Ramsey expected to receive probation in exchange for a guilty plea, the judge sentenced them to 60 days in Parish Prison. When the two were released, 5,000 people greeted them and held a massive parade down Canal Street to a victory rally at Shakespeare Park. If the jail sentence was meant to punish Wright for his organizing efforts, he emerged unrepentant according to the Weekly's account of the rally:

Standing behind the star-spangled blue field of an American flag and beside a sign which carried a line, "Down with Rivers Fredericks and His Gang of Traitors," Wright charged that he was the victim of persons with money who paid to have him jailed and a "lying scandal sheet of a newspaper" which called him a goon. He stated that the 60-day jail sentence was in reality an education, and that now he was willing to fight the battle of the people "until hell freezes over."

Wright continued to organize workers. In September 1941, he was appointed to the regional staff of the CIO and immediately enlisted 3,000 laundry workers making nine cents an hour into the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union. And in August 1942, Wright and five others barely escaped being lynched from the oak trees of Natchitoches, Louisiana, when they were trying to organize sharecroppers. By 1945, he would rise to become general secretary of the New Orleans Industrial Union Council-CIO representing 28 unions and 35,000 workers.

Out of the 1940 insurance strike victory came a new sense of black power in New Orleans, and with it a new organization, the People's Defense League (PDL). The league was the first group of its kind in the city and one that used many of the same strategies and objectives of the civil rights movements of the 1950s and '60s. Established in August 1941, the league adopted the motto "A Voteless People Is a Hopeless People" and mobilized voter registration drives, spoke out against white supremacy and police violence, and advocated the rights of working people. One former member, Oliver White, told a researcher, "The PDL was an organization that I would have said my prayers by." Wright became the league's promotional director. Ramsey, its first president, later recalled Wright and those times:

He was a household word in every black family's home. Wright was the first to organize mass demonstrations. During that time when you were talking about voter registration and marching on the registrar's office, there was no city, state, or federal protection. We marched on raw guts.

Wright made frequent use of raw guts, and the league emerged as the most outspoken critic of police brutality in the city. At the Sunday rallies in Shakespeare Park, he and chairperson Elizabeth Sanders brought victims of police abuse to the podium. For those who did not live to recount their experiences, the league held memorials and solicited money for their families. One such case was that of Felton Robinson, for whom the league conducted a "Memory Day." A mental patient with no history of violence, Robinson was killed in his home by a Twelfth Precinct policeman who fired two shots as the man lay helpless and bleeding on the floor while his wife begged the officer not to kill her husband.

When such incidents occurred, the league wrote protest letters to elected officials who conducted their obligatory inquiries and emerged with the predictable exonerations of the officers. After one particularly acute wave of police misconduct, however, Wright demanded a meeting with the mayor. When the mayor ignored him, Wright rounded up what he called some "thuggish looking Negroes" and made a more direct appeal. The incident is related by Dr. Daniel Thompson in The Negro Leadership Class:

He [Wright] is still amused when he recalls the excitement and frustration of the receptionists "when they looked up and saw all of us rough-looking Negroes waiting to see the mayor. '' At first they attempted to have the visitors wait outside in the hall until the mayor had concluded a "high level" conference. When they refused, the mayor's secretary rushed into his office and within seconds the mayor was out asking them what he could do. Whereupon, the leader told him that this was a committee from the Third Ward and they wanted to talk with him about police brutality. The mayor agreed to talk, but requested that the other members of the group wait outside. The leader refused, and all of them went into the mayor's private office. This leader reported that the mayor was so anxious to get them out that 'he promised us anything we asked for.

By now, Wright was being dubbed the "People's Champion" by many in the community. Because of his influence, the NAACP appointed him promotional director of its membership drive. During the spring of 1942, Wright rode around in a sound truck through the Calliope-Rampart shopping area urging people to join the NAACP, to fight Jim Crowism, and to shop only where they were given respect. This infuriated white merchants, who called the police to arrest him.

Wright elaborated on his views of freedom's responsibilities to a large throng one Sunday in June 1944 in Shakespeare Park during a PDL speech:

The big difference between you and me in this fight for rights is that I am not afraid to die for a principle and you are. I am not afraid to go to jail for a principle and you are. What we need is 10,000 unafraid men as members with their money paid who are unafraid to present themselves to vote and unafraid to present themselves for jobs to which they are entitled. We can't get anywhere by being afraid. Let's stand in our own shoe leather and "walk ye like men.''

These exhortations by Wright and others did not go unheeded. During World War II the PDL, like most black groups across the country, wholeheartedly supported the defeat of the Axis while constantly pointing to the unarguable similarities between the rhetoric of the Third Reich and Southern demagoguery. In support of the war effort, the People's Defense League chaired a drive to raise $50,000 in war bonds and was instrumental in organizing Red Cross donation campaigns. Despite wartime efforts by blacks at home and in the battlefield, racist attacks intensified, leading to riots in Harlem, Detroit, and Fort Dix, New Jersey. New Orleans blacks were outraged when a policeman abused a black woman as she hugged her son good-bye at the induction center.

The PDL continued to grow; a downtown chapter was established in New Orleans's Ninth Ward in 1943, and in 1946 the league was expanding statewide. Meanwhile, Wright had developed a national reputation, addressing labor rallies in places such as South Bend, Indiana, and Detroit. He helped organize Mobile, Alabama, shipbuilding workers into the CIO, and was vice-president of the Louisiana CIO's Political Action Committee. Wright also began writing a syndicated column called "I Daresay," which ran for 15 years in black papers. And people referred to Shakespeare Park as "Wright's Auditorium," as he continued to speak forcibly on labor and political issues. On the electoral front, Wright accepted a post as general secretary of the Louisiana Association for the Progress of Negro Citizens, which was headed by the Reverend A.L. Davis and conducted ballot conventions throughout the state to encourage people to register and vote.

On the national level, the civil rights struggle was gaining momentum as returning black veterans of World War II rejected their status as second-class citizens. Scattered riots occurred across the country. In a small town north of New Orleans, World War II veteran John G. Jones was found hanging from a tree, his eyes gouged by a mob. Adam Clayton Powell, a young black congressman from Harlem who introduced a federal civil rights bill in 1946, spoke at a PDL gathering and told the crowd, "The war is over, the fighting has stopped, but the peace has yet to be won. The days are critical. The Negro must arise and make a challenge for his rights."

The league moved into a seven-room house on Second Street in February 1946 and set up the most intense voter registration campaign the city had ever witnessed. Buoyed by a Justice Department announcement that it would prosecute states which discriminated in registering voters, Wright formed a coalition with the Reverend A.L. Davis, Raymond Tillman of the Transport Union, and former insurance agent Daniel Byrd, who was now state president of the NAACP. Their goal was to put 20,000 blacks on the voting rolls by August 10.

By this time, the PDL had evolved into a highly organized force with ward leaders and precinct captains throughout the city. Their highly spirited membership drives were conducted by such groups as the "Ever Ready Team" of Eva Sylvester, Carrie Mitchell's "Faithful Few," and Moses Turner's "Atomic Squad." Dues were $1.00 per year as the league set its sights on a goal of 5,000 members. It also launched voter registration classes throughout New Orleans in bars, restaurants, barbershops, and churches. A women's division of the league emerged, headed by Ida Johnson with Edna Marie Wright, Ernest's wife, as secretary.

League president Richard L. Perry summarized the spirit of the times at one of the many voter rallies held in 1946: "Many barriers have been put in the way of the members of our organization to keep them from registering. These barriers are only stepping stones, however, because the Negro people are determined to participate in politics, and the devils in hell shall not prevail against them." Displaying this determination, one elderly man who was constantly rebuffed at the registrar's table, returned daily, telling Wright, "I got nothing but time. If they say it [the registration card] is wrong, you will see me tomorrow."

As the August voter registration deadline approached, the league organized fleets of cars, trucks, and church buses to ferry people down to the registrar's office. PDL members scoured their neighborhoods in search of potential voters. And Wright addressed an overflow crowd gathered in the league's auditorium on Second Street:

From the pulpits to the docks along the Mississippi River, in the labor union halls, on the street cars, in the comer grocery stores, barrooms and the fraternal halls, the importance of registering to vote is spreading like a forest fire. The job of arousing the colored citizens to register and vote in all city and state elections is not completed. There is need for a great deal more education before the majority of eligible voters among us will have accepted their responsibility. But one thing is certain, the New Orleans Negroes are on the march and their political power will continue to manifest itself day after day!

Veteran Louisiana Weekly reporter "Scoop" Jones described the final days of the campaign:

Hundreds stood in the heat on the shady side of the Registrar's office on Lafayette and St. Charles Street Friday afternoon long before the opening of the office. Many of these people were still in line when closing time came, and were back again the next morning. Some of these were lucky to register, while others failed to get even to the registrar's desk.

When the final tally was made public, 4,716 blacks had been accepted; six out of 10 were rejected due to a "mistake on your card." Despite the failure to reach their goal, the PDL became an electoral voice which could no longer be ignored. That year two candidates for the school board addressed a league meeting and asked for the group's support. And a narrow upset victory by reform candidate Chep Morrison over Mayor Maestri proved the power of the black vote. Even Maestri's "Old Regular" machine conceded the emerging strength of the black voter and drafted a somewhat humble "five-point plan for the Negro."

By 1950, the People's Defense League had branches in 26 parishes (counties) throughout Louisiana. Black registration in New Orleans climbed to 26,000. However, when Wright established ties with Earl Long's "Old Regular" machine which controlled many of the state offices, his dealings in the seamy world of party politics led to a decline in his stature as a civil rights leader. Wright hoped to use the alliance to liberalize the voter registration office so more blacks could be added to the rolls, but his abandonment of his mass base in favor of a much maligned political faction caused his influence to deteriorate.

The PDL closed its doors in 1954, giving way to a host of other black political organizations aligned with then-mayor Chep Morrison and the emerging Civil Rights Movement. Wright, then in his mid-forties and with a growing family, had left in 1952 to work full-time for the Teamsters. In 1957, because of his role in the 1940 insurance strike, he became a subject of investigation by the Louisiana Committee on Subversion in Racial Unrest, a legislative body bent on linking the growing civil rights movement with foreign agents.

Although Wright never regained his earlier power, he remained visible in political and civic circles. In 1960, he was at the forefront of a group called Frontiers, Inc., which supported school integration efforts in New Orleans. And in 1963 he ran for governor and received nearly 40,000 votes in a campaign based on little more than name recognition. People remembered that it was Wright who pushed back the mountains to plant the seeds of black political participation. And before he died in 1979, Wright saw New Orleans elect Dutch Morial as its first black mayor.

Tags

Keith Weldon Medley

Keith W. Medley is the former co-host of the WYES television station show Nationtime and served as a delegate to the national steering committee for the African Liberation Support Committee. A student activist at Southern University in New Orleans during the 1960s and '70s, his work has appeared in Black New Orleans magazine and Facing South. He currently lives and writes in New Orleans. (1984)