Republican redistricting strategy limits public input

Texas took its newly drawn political maps to federal court this week, asking a panel of judges to review the proposed congressional, legislative and state Board of Education districts for compliance with the Voting Rights Act.

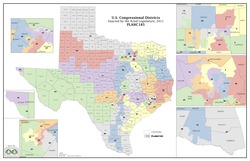

Texas took its newly drawn political maps to federal court this week, asking a panel of judges to review the proposed congressional, legislative and state Board of Education districts for compliance with the Voting Rights Act.Section 5 of the Act, which bans racial discrimination in voting practices, requires that either the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) or a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia "preclear" voting changes in covered jurisdictions, which include much of the South.* The Texas filing said the new maps (the proposed congressional map is shown above; click on it for a larger version) "have neither the purpose nor will they have the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority."

As Facing South has reported, Republican lawmakers in some states have decided to take the preclearance route through the courts rather than submit their maps to President Obama's DOJ, which they fear will overly politicize the approval process.

While Texas also informally submitted its plans to the DOJ in hopes of speeding approval, that did not assuage critics of the court-route strategy. They include state Rep. Trey Martinez Fischer (D-San Antonio), chair of the Mexican American Legislative Caucus, who called the move "disappointing."

The Republican-controlled legislature in North Carolina, where a contentious redistricting process is also underway, has also said it plans to bypass Justice.

Going the court route is more expensive and time-consuming. It also makes it more difficult for the public to weigh in on the plans.

Anita Earls, a civil rights attorney who directs the Southern Coalition for Social Justice in Durham, N.C. and who served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the DOJ's Civil Rights Division under President Clinton, brought up the problem of public exclusion during a panel discussion on redistricting held earlier this week at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. (her remarks came around 1:07):

From a public point of view, if you go to the D.C. District Court, it makes it harder for individual people who want to comment on the plan to have a role. Because the Justice Department process at least allows for pretty easy public comment, whereas if it goes to court you would have to intervene, you know, have legal representation. It becomes a very different process.The Republican strategy making it harder for citizens to have input on the redistricting plans comes as the new maps put a great deal at stake politically, especially for minority communities.

Texas is already facing multiple lawsuits over maps approved this year by its state lawmakers, with 15 lawsuits pending so far, according to the website All About Redistricting. Among the suits' claims is that the growth in minority seats does not match the growth of minority populations in Texas. Earls pointed out that there are concerns in a number of states that the Latino population boom is not being reflected in new district maps.

And Latinos are not the only minority group with concerns about new maps. In North Carolina, a state with a contentious redistricting history, U.S. Rep. Mel Watt (D-12th) criticized the Republicans' first shot at drawing a congressional map for packing African-American voters into his district and diluting their power elsewhere. He accused the plan of violating the Voting Rights Act and said it represents "a sinister Republican effort to use African Americans as pawns in their effort to gain partisan, political gains in Congress."

And Latinos are not the only minority group with concerns about new maps. In North Carolina, a state with a contentious redistricting history, U.S. Rep. Mel Watt (D-12th) criticized the Republicans' first shot at drawing a congressional map for packing African-American voters into his district and diluting their power elsewhere. He accused the plan of violating the Voting Rights Act and said it represents "a sinister Republican effort to use African Americans as pawns in their effort to gain partisan, political gains in Congress."A second draft of the North Carolina congressional map (shown above; click on it for a larger version) was released this week and is being evaluated by voting rights advocates. However, litigation over how the lines have been drawn is widely expected.

Meanwhile, voting rights watchdogs promise they'll continue to fight to ensure the law is followed, regardless of efforts to bypass the public.

"We continue to advocate for what we think the law says, and we'll advocate in whatever forum or jurisdiction we need to," Earls said.

* All of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Texas; 158 of Georgia's 159 counties; 84 of Virginia's 95 counties; 40 of North Carolina's 100 counties; and five of Florida's 67 counties.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.