NC backslides on voting rights by disqualifying 'right church, wrong pew' ballots

Among the many controversial elements of North Carolina’s new Voter Information Verification Act (VIVA), which requires a photo ID to vote, is the disqualification of provisional ballots cast in the wrong precinct, even if in the right county or district -- so-called “right church, wrong pew” ballots.

The new restriction is one of the targets of lawsuits filed against the state by the U.S. Justice Department and civil rights groups. N.C. Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger (R-Rockingham) and House Speaker Thom Tillis (R-Mecklenburg) criticized the lawsuits, issuing a statement that the new law "brings North Carolina's election system in line with a majority of other states."

Not quite.

For one thing, while over half of all states require some form of voter ID, very few have the kind of provision that North Carolina included in VIVA -- what the National Conference of State Legislatures labels a "strict" photo ID requirement due to the short list of IDs eligible for voting.

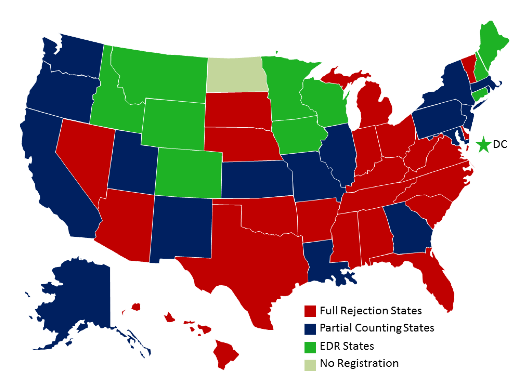

Berger and Tillis are also wrong about the number of states that disqualify "right church, wrong pew" provisional ballots. A report released this week by the Fair Elections Legal Network finds that North Carolina is one of only 22 states that fully reject ballots cast in the wrong precinct. The other 28 states either count some portion of the ballot or have a same-day registration safety net so voters never cast from the wrong polling place.

Of those 28 states, 17 will partially count a ballot, meaning some or all of the candidates the "wrong pew" voter selected will count so long as that voter lives within the jurisdiction of the person he or she voted for. For example, a voter could be in his or her home county, but vote at the wrong precinct or polling place, perhaps due to a recent move. That person's votes cast for, say, U.S. president or senator would count, since he or she is in the right jurisdiction. But if the person voted for a city council candidate for a district he or she doesn’t live in, then that part of the ballot would not count, though the rules vary among the states.

In the other 11 states, if a voter mistakenly shows up at the wrong precinct, then thanks to same-day registration he or she could simply correct the information at the polling place.

According to FELN, 45,376 ballots nationwide were completely rejected in the 2012 general election because they were cast in the wrong precinct or wrong county.

North Carolina used to be among the majority of states that helped “wrong pew” voters. Before VIVA was passed, the state not only had same-day registration but also counted the eligible votes on a provisional ballot cast in the correct county but incorrect precinct. According to FELN, in the 2012 elections this helped save 6,700 votes across North Carolina that otherwise would have been thrown out.

But since passing the new law, says FELN, North Carolina has "traded places" with Illinois, once notorious for elections corruption. Now, as one of the 28 states that partially count “wrong pew” provisional ballots, Illinois is "making progress on behalf of voters" while North Carolina is "backsliding," according to the report.

The Justice Department's complaint filed against VIVA asserts that North Carolina's elimination of the provisional ballot safety net and same-day registration will have a disproportionate impact on black voters in the state.

"Data from past elections indicate that prohibiting the counting of provisional ballots cast in the voter's county, but outside the voter's home precinct, will likely mean the rejection of several thousand votes that would have been counted in prior elections, and indicate that African-American voters can be expected to cast disproportionately more of these rejected ballots than white voters," states the complaint.

The Justice Department is suing under Section Two of the Voting Rights Act, which protects people of color from laws that block or abridge their voting rights on account of race. Attorney General Eric Holder is also suing under Section Three to bring North Carolina under federal supervision of its election laws, claiming that state lawmakers intentionally created these new rules to undermine voters of color.

The evidence for those intentions will come out in the discovery phase and the trial itself. But North Carolina history provides egregious examples of lawmakers shutting blacks out of the polls -- sometimes through violence.

This history was explored in election law scholar Rick Hasen's recent article in the Harvard Law Review Forum titled "Race or Party? How Courts Should Think About Republican Efforts to Make it Harder to Vote in North Carolina and Elsewhere." It begins with a reference to J. Morgan Kousser's 1974 book "The Shaping of Southern Politics," which recounts a time North Carolina had the reputation for "perhaps the most democratic" political system in the late-19th century South due to reforms that allowed many African Americans to vote and even win public office.

But those reforms bred a backlash from racist white North Carolinians who mounted campaigns that successfully rolled back the franchise expansions through amendments to the state constitution. One of the new rules was, as Hasen quotes Kousser, "that any ballot placed in the wrong box -- there were six -- whether by election officers or the voter himself, would be void."

On the eve of an 1898 plebiscite over a disenfranchising state constitutional amendment, one North Carolinian, former Congressman Alfred Moore Waddell, told a crowd, "You are Anglo-Saxons. You are armed and prepared, and you will do your duty. … Go to the polls to-morrow, and if you find the negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls, and if he refuses, kill him." The amendment passed.

If past is indeed prologue, as Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in her dissent from the Shelby v. Holder opinion that gutted the Voting Rights Act, then this history is crucial in understanding the possible impacts of VIVA. Of the 22 states that fully reject mistaken-voter provisional ballots, 10 of them are Deep South, former Jim Crow states. Of the 13 Southern states*, only Georgia and Louisiana partially accept mistaken precinct provisional ballots, and none currently have same-day registration.

So when Berger and Tillis said VIVA aligns North Carolina with a majority of other states, perhaps they were referring to former Jim Crow states -- not the best company to be in when it comes to voting rights.

* The Institute for Southern Studies counts the following states as part of the South: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia.