Concerns grow over voting rights for the South's language minorities

Election reform and voting rights advocates argue that making voter registration easier is a critical first step to expanding voting access. (Photo by Erik Hersman via Flickr.)

Amid concerns over the rollback of the Voting Rights Act and introduction of voter ID laws, election watchdogs worry about another critical voting rights issue: language barriers faced by limited English proficient (LEP) voters.

For people who don't speak English as their first language, language barriers can be a significant hurdle to voting. Difficulty understanding registration forms, ballots and other voting materials for LEP voters such as recently-naturalized citizens may discourage them from turning out to the polls.

In 1975, Congress acknowledged the barriers an English-only voting process created and amended the Voting Rights Act to require certain jurisdictions to provide bilingual materials and translation support to voters. Under Section 203, jurisdictions -- usually counties -- where a certain level of a language minority are LEP and have an illiteracy rate higher than the national average must provide translated voting materials and an interpreter at the polls.

Section 203 applies to Latino, Asian, Native American and Alaska Native language minorities and covers counties largely in the West, the Southwest and major metros as well as Hawaii and Alaska. In the South, few counties outside of Texas and Florida are covered, but those include Fairfax County in Virginia and several counties in Mississippi that are home to the Choctaw Indian tribe. On the other hand, a diverse immigrant hub like Harris County, Texas, home to Houston, is required to provide translated voting materials in Chinese, Spanish and Vietnamese.

LEP voters in jurisdictions not covered by Section 203 are also able to access the ballot through another VRA provision that allows them to bring an interpreter with them to the polls. Section 208 was added in 1982 and allows voters who need assistance due to blindness, disability or inability to read or write to bring someone of their own choosing to help them cast a ballot. The measure also applies to those who face language barriers, although the specifics of the law vary by state.

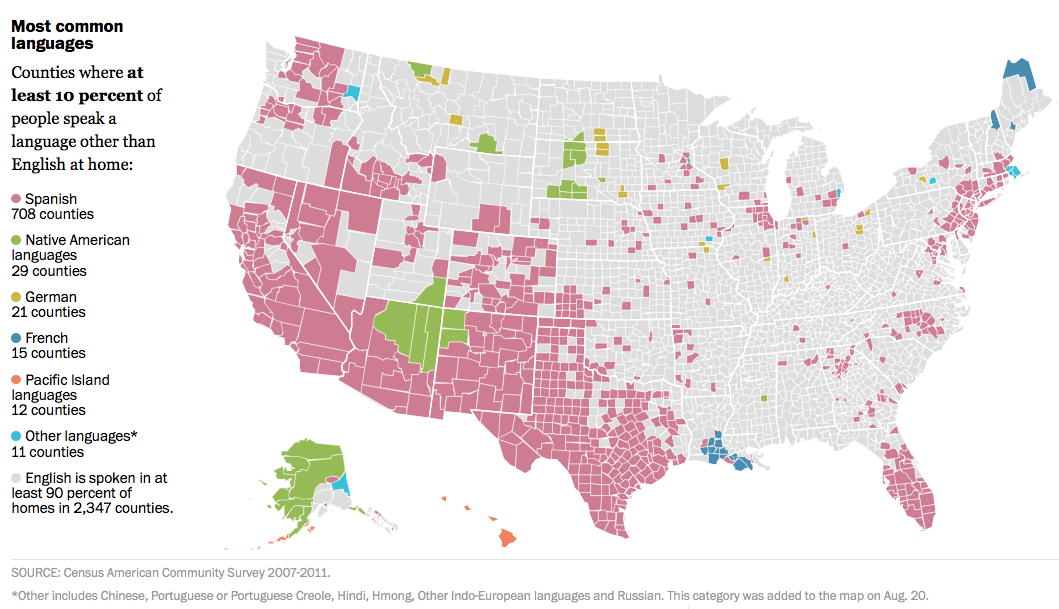

Section 208 will become increasingly important in the South, where language minority populations are growing but not enough to trigger Section 203 requirements. Already across the region there are several counties where at least 10 percent of the population speaks another language at home, as seen in this map from the Washington Post:

"For Limited English Proficient (LEP) voters, [these measures] could mean the difference between casting their ballot and not participating in the democratic process," Mee Moua, president of Advancing Justice | AAJC, told NBC, noting the drop in turnout rates among LEP Asian-American voters. Her organization launched a major effort last fall to reach out to eligible voters in their native languages and opened a hotline for Asian-American voters to report any issues.

"For Limited English Proficient (LEP) voters, [these measures] could mean the difference between casting their ballot and not participating in the democratic process," Mee Moua, president of Advancing Justice | AAJC, told NBC, noting the drop in turnout rates among LEP Asian-American voters. Her organization launched a major effort last fall to reach out to eligible voters in their native languages and opened a hotline for Asian-American voters to report any issues.

Those voting issues often occur because these lesser-known measures of the VRA are not uniformly enforced -- particularly Section 208, which is not a countywide mandate.

In the midterm elections last November, Election Protection Coalition monitors reported instances of Asian-American voters in North Carolina and Pennsylvania who were not allowed to bring interpreters with them to the polls. Similarly, an October 2014 Advancing Justice report found that Vietnamese-speaking voters in Louisiana were not allowed to have a translator with them at the polls in the 2012 election because poll workers weren't aware of the law.

Confusion about the provisions of the law also sets the stage for intimidation of LEP voters. Last year in Pickens County, Georgia, an Election Protection Coalition monitor reported that a poll worker "threatened to call the police on a woman who was helping her husband with limited English proficiency cast a ballot," even though she is allowed to do so under Section 208. Meanwhile in Louisville, Kentucky, election monitors reported cases of poll workers treating Latino voters rudely or failing to help them.

"As we've seen across the country, as Latinos become a growing demographic, we see backlash," Arturo Vargas, an election monitor whose group offered a Spanish election hotline, told the Los Angeles Times.

With increasingly loud rhetoric about non-citizen voting, particularly following President Obama's expansion of deportation relief programs, the threat of intimidation may be another factor beyond language challenges that could discourage LEP voters from exercising their right to vote.

Tags

Allie Yee

Allie is a research fellow at the Institute for Southern Studies and is currently studying at the Yale School of Management. Her research focuses on demographic change, immigration, voting and civic engagement.