Analysis reveals urban-rural divide in poverty in Southern schools

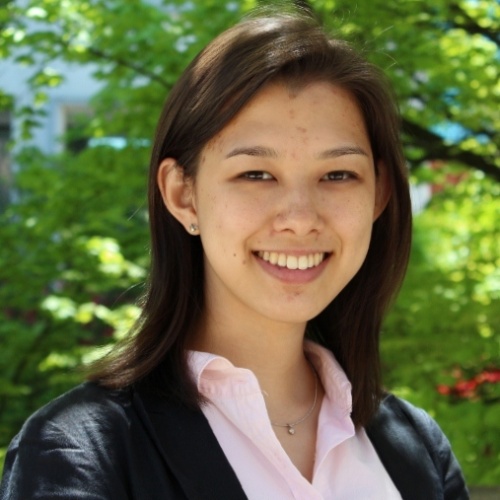

This map from the Urban Institute shows that place matters for school poverty. Click here to see the interactive version.

The South has some of the highest rates of low-income students in public schools. Since the 2004-2005 school year, the majority of the region's public school students have been low-income (defined as eligible for free or reduced price lunch), according to data from the Southern Education Foundation. In 2013, that became the case for public schools nationwide.

In a report released this week, the Urban Institute drilled deeper into the data to look at trends beyond the state level. The county-level data revealed that poverty in schools, like poverty in general, is concentrated unevenly across counties and across race.

Report author Reed Jordan pointed to a significant urban-rural divide in the South:

"A closer look reveals that large shares of low-income areas in the South are often rural. In many rural parts of Kentucky (such as Jackson, Owsley, and Clay Counties), 60 percent or more of all students are from low-income families. A similar belt of rural poverty stretches across Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia."

The map above by the Urban Institute shows those belts of rural poverty across the South.

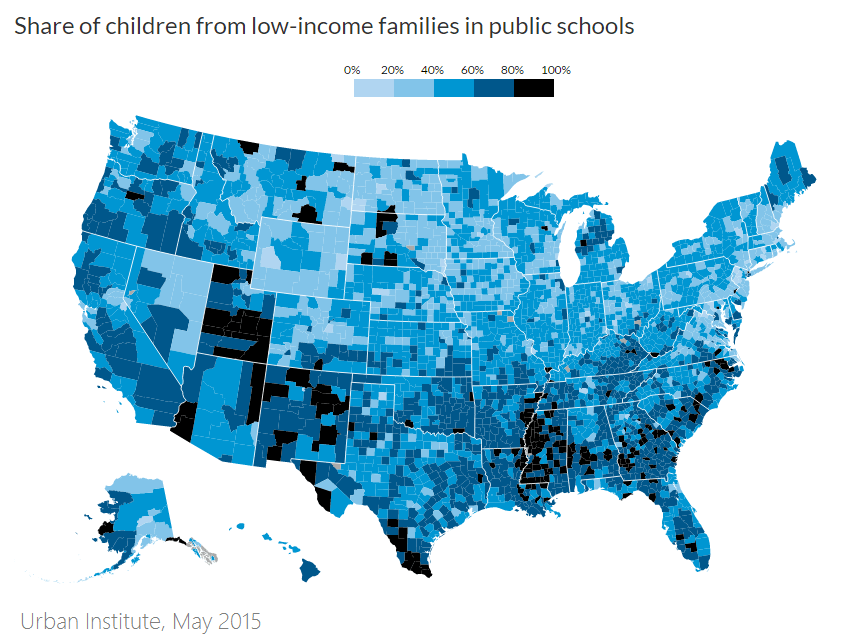

The report also dug into the concentrations of low-income students and black students in high poverty schools. It found that, nationwide, both groups are six times more likely than their non-poor and white counterparts to attend high-poverty schools, where 75 percent or more of students are low-income. But the analysis reveals a unique dynamic in the South: Although non-poor and white students in the region are less likely to attend high-poverty schools, they are more likely to do so compared to their counterparts in other regions of the country.

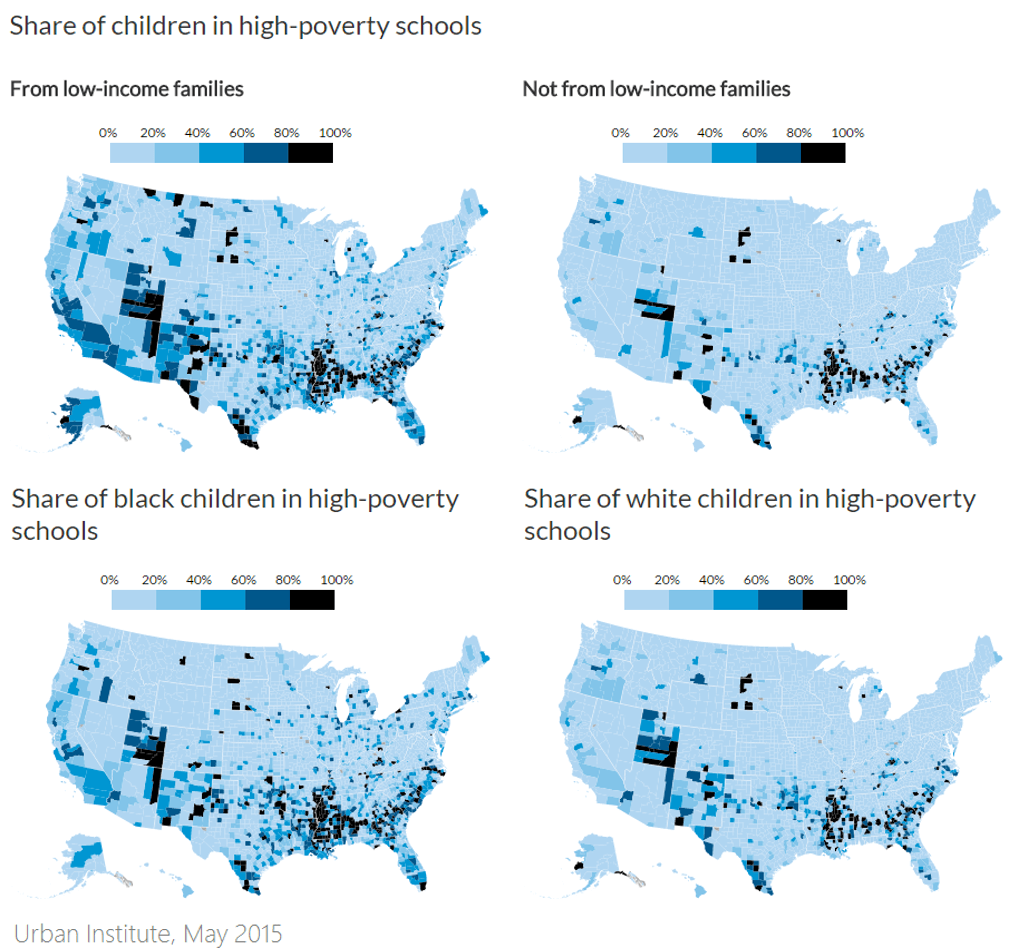

A recent map of economic mobility from Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren shows the South is the region with the least economic mobility. Given the critical role education plays in economic mobility, it's not surprising that these maps track each other so closely.

Noting that public schools must provide a good quality education to all students regardless of race or income, Jordan of the Urban Institute cites initiatives like school integration efforts in Louisville, Kentucky for helping address disparities.

"But our school system alone can't solve the problem," Jordan writes. "We have the policy tools — in both housing and schools — backed by solid research to address concentrated poverty. Doing so is imperative for our children, our schools, our neighborhoods and cities."

Tags

Allie Yee

Allie is a research fellow at the Institute for Southern Studies and is currently studying at the Yale School of Management. Her research focuses on demographic change, immigration, voting and civic engagement.