Civil rights battle over N.C. hog industry regulation heats up as negotiations break down

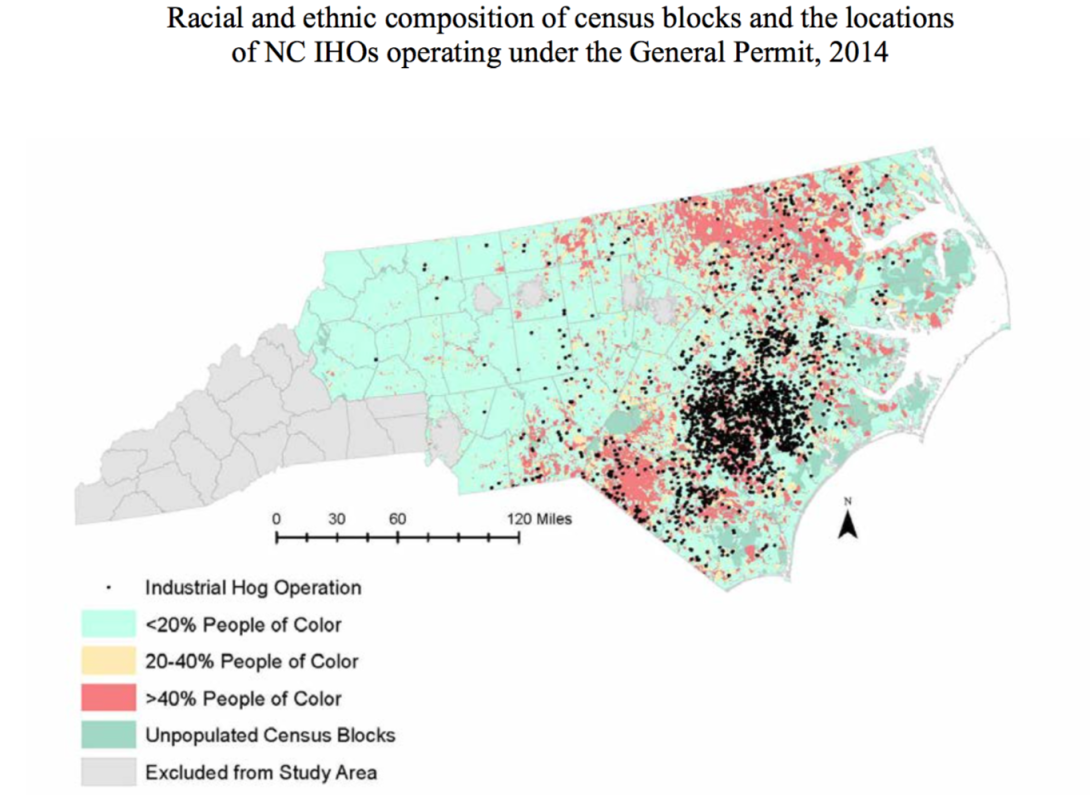

This map showing the proximity of industrial hog operations to communities of color in North Carolina is from a 2014 paper by UNC researchers Steve Wing and Jill Johnston. Click on it for a larger version.

Negotiations between community advocates and North Carolina's environmental agency over charges that lax oversight of hog farms disproportionately harms African-American, Latino and Native American communities broke down recently after the Department of Environmental Quality attempted to bring industry representatives into what were supposed to be confidential mediation proceedings.

"I've been a civil rights attorney for a long time, and I've never seen anything like this," said Elizabeth Haddix, attorney at the University of North Carolina's Center for Civil Rights, which is representing the complainants along with the nonprofit law firm Earthjustice. "Having the regulated industry barge in – despite our clear opposition but with DEQ's support – insisting that they have a right to be at the table to resolve a race discrimination case against DEQ could not be more telling or offensive."

Back in 2014, the DEQ under the current administration of Gov. Pat McCrory (R) issued a general permit covering more than 2,000 of the state's industrial hog operations, allowing them to continue flushing the animals' waste into open pits and spraying it onto nearby fields — even though the practice has led to water contamination and subjects nearby residents to terrible odors and health-damaging air pollution.

Hog operations are concentrated in eastern North Carolina, the historic center of the state's African-American population. The region is also home to the state-recognized Lumbee Tribe and growing numbers of Latinos. Given the demographics, it's not surprising that an analysis by UNC researchers found that impacts from hog operations under the DEQ-imposed permit conditions are disproportionately felt by rural communities of color:

…[T]he proportion of [people of color] living within 3 miles of an industrial hog operation is 1.52 times higher than the proportion of non-Hispanic Whites. The proportions of Blacks, Hispanics and American Indians living within 3 miles of an industrial hog operation are 1.54, 1.39 and 2.18 times higher, respectively, than the proportion of non-Hispanic Whites … In census blocks with 80 or more percent people of color, the proportion of the population living within 3 miles of an industrial hog operation is 2.14 times higher than in blocks with no people of color. This excess increases to 3.30 times higher with adjustment for rurality.

Citing this disproportionate racial impact, the N.C. Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN), Rural Empowerment Center for Community Help, and Waterkeeper Alliance filed a complaint against DEQ in 2014 with the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Civil Rights under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which requires that recipients of federal funds like DEQ ensure their actions don't harm individuals or communities based on race. The EPA accepted the complaint for investigation last year.

The complainants agreed to enter into settlement negotiations with DEQ in hopes of resolving the matter without federal intervention. But when they showed up for talks at the offices of the UNC Center for Civil Rights in Chapel Hill recently, they were shocked to find representatives of the N.C. Pork Council and the National Pork Producers Council there, demanding a seat at the table. The complainants say the industry's presence was intimidating to community members who've experienced retaliation from hog industry supporters.

"The Pork Council's presence at a mediation session – which was supposed to be known only to DEQ representatives, the complainants and the mediator – crystalizes our concerns about our voices ever being heard," said Naeema Muhammad, NCEJN's co-director.

The hog industry has long had a cozy relationship with state government in North Carolina, the nation's second-biggest hog-producing state after Iowa. Back in 1995, the News & Observer of Raleigh published a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative series that documented how state officials helped the industry expand but were slow to address resulting problems.

While those problems emerged when the state was still under Democratic control, they've continued under Republican rule. Last year, for example, even while the state was facing the civil rights complaint over hog farm regulation, Gov. McCrory attended a rally held by an industry group representing companies including Smithfield Foods and Murphy-Brown, both owned by Chinese pork giant Shuanghui Group, to oppose lawsuits over their environmental practices. McCrory told those at the industry rally that state government would fight for them.

Advocates for those who have to suffer the consequences of the way the industry operates accuse the McCrory administration of being "in bed with Big Pig." That's why they've renewed their call for the federal government to investigate their claims that DEQ's permitting decision violated federal law.

"The agency has clearly been captured by the industry," Haddix said. "This is the opposite of how government is supposed to work."

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.