U.S. Supreme Court may finally define racial gerrymandering in cases from the South

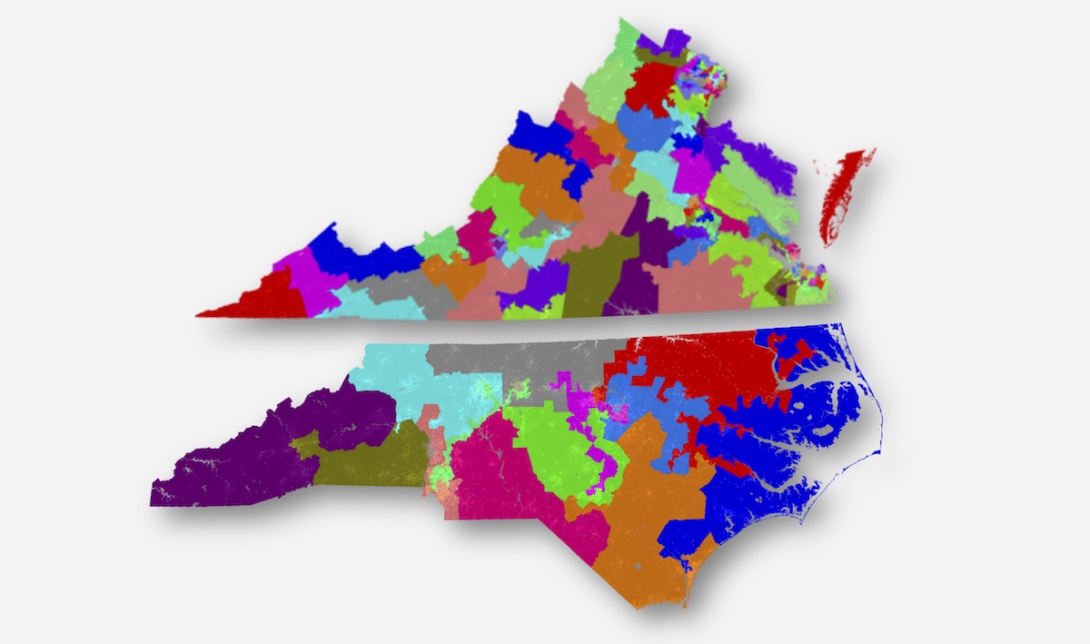

This week the U.S. Supreme Court took up cases involving potentially racially gerrymandered congressional districts in North Carolina and state legislative districts in Virginia. The rulings are expected to define for the first time what constitutes excessive reliance on race when drawing district lines. (Above maps are from Brian Olson's redistricting website.)

The U.S. Supreme Court held hearings on Dec. 5 in two cases regarding racial gerrymandering, the practice of drawing voting districts in a way that undermines the political power of a racial group.

In the cases from North Carolina and Virginia, lower federal courts have considered whether state legislators relied too heavily on race when drawing congressional and state legislative districts. The contested maps pack black voters into a small number of districts thereby diluting their influence in surrounding districts. The court is considering whether the maps violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

The Supreme Court has not yet created a legal standard for unconstitutional racial gerrymandering, so lower courts have had to rely on their own interpretations of what constitutes excessive reliance on race when drawing voting maps.

"It's kind of a Goldilocks problem," elections law expert Rick Hasen told Politico. "You must take race into account somewhat to comply with the Voting Rights Act, but if you take into account too much the racial considerations you can get in trouble as well. The question is how do you know when you've gotten it just right."

In the Virginia case, voters represented by the law firm Perkins Coie contested 12 state legislative districts drawn by Republican lawmakers in 2011 to contain at least a 55 percent black majority. The lawsuit argues that it was unnecessary for those districts to have such a high percentage of African Americans in order for voters to elect black representatives. A federal district court upheld the districts, so the plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Marc Elias, an attorney representing the plaintiffs, rejected the idea that the Virginia districts were an attempt to comply with the Voting Rights Act by creating districts where black candidates could win elections. He called it "racial sorting, pure and simple."

Federal courts have already ruled that Virginia state legislators racially gerrymandered voting districts. In January, a federal court panel imposed two redrawn congressional districts in the state after finding that legislators had packed too many African Americans into the 3rd Congressional District. In an appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court let the revised maps stand.

Weakening black influence in North Carolina

The North Carolina case that the U.S. Supreme Court is considering involves two congressional districts drawn in 2011 by the Republican-controlled legislature that have spindly tentacles extending in all directions. The Republican-controlled North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the districts, but a federal district court ruled that mapmakers had relied too heavily on race and that the districts were unconstitutional racial gerrymanders that weakened black voters' influence in surrounding districts.

North Carolina legislators were forced to redraw a number of congressional districts for the 2016 election, resulting in delayed congressional primaries. But lawyers representing the state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, hoping to overturn the district court's ruling and claiming the maps were drawn for purely political and not racially discriminatory purposes.

Even with the new 2016 maps, only three out of North Carolina's 13 congressional seats are represented by Democrats, whom the state's black voters heavily favor, even though Democrats received 47 percent of congressional votes statewide this year.

Congressional districts aren't the only ones in question in North Carolina. In August, a federal court ruled that 28 of North Carolina's state legislative districts were racially gerrymandered when drawn in 2011. On Nov. 29, the same panel of judges ordered North Carolina to redraw those districts and hold special elections next year to fill them.

"While special elections have costs, those costs pale in comparison to the injury caused by allowing citizens to continue to be represented by legislators elected pursuant to a racial gerrymander," wrote the judges.

North Carolina has already appealed the ruling on its legislative districts to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court's ruling on the state's congressional districts, expected next summer, will have a major impact on the case.

Even worse in the Deep South

While racial gerrymandering is a concern in states in the upper South, it's even worse in the Deep South.

According to research by Appalachian State professor William Hicks, Texas Tech professor Seth McKee and professor Dan Smith and post-doctoral associate Carl Klarner of the University of Florida, state legislative districts in the Deep South need to be even more heavily African-American than those in the upper South in order to elect a black representative, thus further diluting black political power in the surrounding districts. The researchers classify Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina as the Deep South states.

In recent years courts have ordered racially gerrymandered districts to be redrawn in Alabama. In 2012, the Alabama Legislative Black Caucus sued the state over its legislative maps, arguing they were racially gerrymandered to dilute black voting power. Three years later, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the plaintiffs, ruling that the mapmakers relied too heavily on race when designing the districts. It remanded the case back to a lower federal court, which requested new maps from the plaintiffs.

Smith predicts that in 2021, when the next round of nationwide redistricting occurs, "most Democrats will push for a reduction in the size of minority populations in majority-minority districts, while almost every Republican will continue to insist that majority-black districts should remain as is, or better yet, contain even higher African-American populations."

The Supreme Court's rulings in the North Carolina and Virginia cases will help determine just how much mapmakers can rely on race when drawing new districts.

Tags

Alex Kotch

Alex is an investigative journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, and a reporter for the money-in-politics website Sludge. He was on staff at the Institute for Southern Studies from 2014 to 2016. Additional stories of Alex's have appeared in the International Business Times, The Nation and Vice.com.