Trump immigration policies define local sheriff races

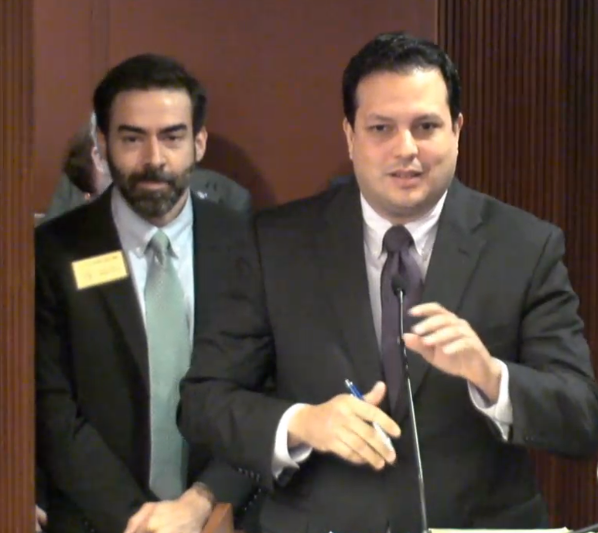

Georgia judges Dax Lopez (right) and Mike Jacobs (left) speak out against a bill in the state legislature that would require police and judges to ask certain people about their citizenship status and report it to ICE. (Image is a still from this Georgia House video.)

As more local law enforcement agencies sign on to the Trump administration's immigration crackdown, some candidates for sheriff are pushing back and promising not to help enforce federal immigration law. Candidates in some Southern cities are criticizing incumbent sheriffs for detaining immigrants, who would otherwise be released, at the request of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). These "detainers," which do not require a warrant signed by a judge, have been ruled unconstitutional by federal courts.

Cooperation with ICE has become a key issue in two sheriff elections in North Carolina. In Mecklenburg County, which includes Charlotte, the controversial 287(g) program has come under fire from two candidates challenging Sheriff Irwin Carmichael. Under the program, which is named after a federal immigration regulation, local law enforcement agencies can enter into agreements with ICE that allow them to check arrestees' immigration status and jail those who are here illegally.

Garry McFadden, a former Charlotte police officer who's running against Carmichael, says the program leads immigrants to distrust the police. "Imagine crimes being committed in your neighborhood but your fear of talking to police makes you not report those crimes," he said. Antoine Ensley, another former police officer running in the sheriff's primary, argues that the federal government is responsible for enforcing immigration laws. Carmichael defended the program's purpose as "safety and security."

In Durham County, North Carolina, Sheriff Mike Andrews has faced criticism for honoring ICE detainers. Running against him is Clarence Birkhead, who says he will not honor detainers without a valid warrant.

Although 18 Texas counties signed 287(g) agreements with ICE last year, Travis County Sheriff Sally Hernandez was elected in 2016 on a pledge to end the county's previous cooperation with ICE. Hernandez, whose jurisdiction includes Austin, promptly changed the county's policies on detainers when she took office.

In some counties, local law enforcement has been criticized for using its authority under 287(g) to round up immigrants, rather than merely checking the immigration status of those who happened to be arrested. Some sheriffs have faced charges of racially profiling Latinos in their efforts to arrest undocumented immigrants.

For example, North Carolina's Alamance County was sued by the U.S. Justice Department in 2012 for discriminating against Latinos in traffic stops and other enforcement actions, and its 287(g) agreement was terminated. Evidence emerged that Alamance deputies used racial slurs like "wetback," but Sheriff Terry Johnson denied the allegations. Johnson said that ICE contacted him last year to invite him to reapply for the 287(g) program.

Boosting pro-reform candidates

A 2011 study by the Migration Policy Institute noted that Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, was a pioneer in using 287(g) to apprehend as many immigrants as possible. The study counted the ICE detainers that resulted from traffic violations in the counties with 287(g) agreements and found that the 10 counties with the most detainers were all in the South. Even though they're much smaller in population than other 287(g) jurisdictions, those 10 counties accounted for one-third of all the detainers resulting from traffic violations.

The study said that this "regional pattern reflects common political pressures that stem from rapid demographic change." Growth in immigrant populations in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee from 1990 to 2009 "provoked a public reaction against the perceived costs of immigrants" that pressured sheriffs to participate in 287(g), the study concluded.

The Trump administration has ramped up 287(g) agreements and tried to crack down on so-called "sanctuary cities" that do not want to detain people on ICE's behalf. In January, ICE signed new 287(g) agreements with 17 Florida counties. Obviously, many candidates for sheriff embrace the Trump administration's anti-immigrant agenda. This is particularly true in the South, which is home to nearly two-thirds of the current 287(g) agreements.

However, the emergence of anti-detainer sheriff candidates may be a part of a broader trend of reform-focused candidates running for law enforcement and prosecutorial positions.

Black Lives Matter activist and writer Shaun King, along with veterans of the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign, started the Real Justice Political Action Committee to support the campaigns of diverse reformers in elections for prosecutors, sheriffs, and judges. The PAC began in 2017 when it supported Portsmouth, Virginia, prosecutor Stephanie Morales and Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, who has undertaken far-reaching reforms in a city noted for police and prosecutorial corruption.

The Real Justice PAC is now supporting district attorney candidate Joe Gonzales in San Antonio. In a primary held earlier this month, Gonzales unseated incumbent Democrat Nico LaHood, who came under fire for bullying defense attorneys and siding with the president on immigration matters.

"It's shameful that the current district attorney refuses to stand up for immigrants and defend his constituents from Trump's heartless deportation campaign," Becky Bond, one of the PAC's founders, said in endorsing Gonzales.

Punishing police and judges who resist ICE

Texas sheriffs who refuse to jail undocumented immigrants at the request of ICE could soon find themselves behind bars. A federal court recently upheld a Texas law that threatens local sheriffs and other elected officials with fines and even jail time for refusing to comply with ICE directives. The state's largest cities and some border communities challenged the law in court, and the Trump administration sided with Texas in its defense.

Meanwhile, after Atlanta and two neighboring cities in Georgia sought to avoid a role in immigration enforcement, a bill was introduced in the state legislature that would have mandated local cooperation with ICE. The social justice advocacy group Project South echoed the sentiments of other critics when it called the bill "unconstitutional, harmful to our communities, and economically wasteful."

After the Georgia Senate passed the bill, legislators in the House watered down its language so cooperation is not mandatory, but they did not remove a provision that requires judges to ask defendants in criminal cases about their citizenship status during sentencing and report undocumented immigrants to ICE.

Georgia Judge Mike Jacobs warned that the bill puts judges in a tough spot. "I am now tasked with making a determination regarding a very nuanced and ever-changing area of the law on which our judges are not specifically trained, certainly not as to all of the aspects of it," he told legislators. Judge Dax Lopez said it also raised concerns about separation of powers. The revised bill passed out of a committee in the Georgia House of Representatives earlier this week.

At the same time Georgia legislators were considering mandating ICE cooperation, the agency was working to expand the 287(g) program in the state. This week it was reported that the Trump administration signed agreements to cooperate with the sheriffs in Bartow and Floyd counties as well as with the Georgia Department of Corrections. They join the four other Georgia counties — Cobb, Gwinett, Hall, and Whitfield — that already participate.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.