Poverty continues to prevent many ex-felons from voting

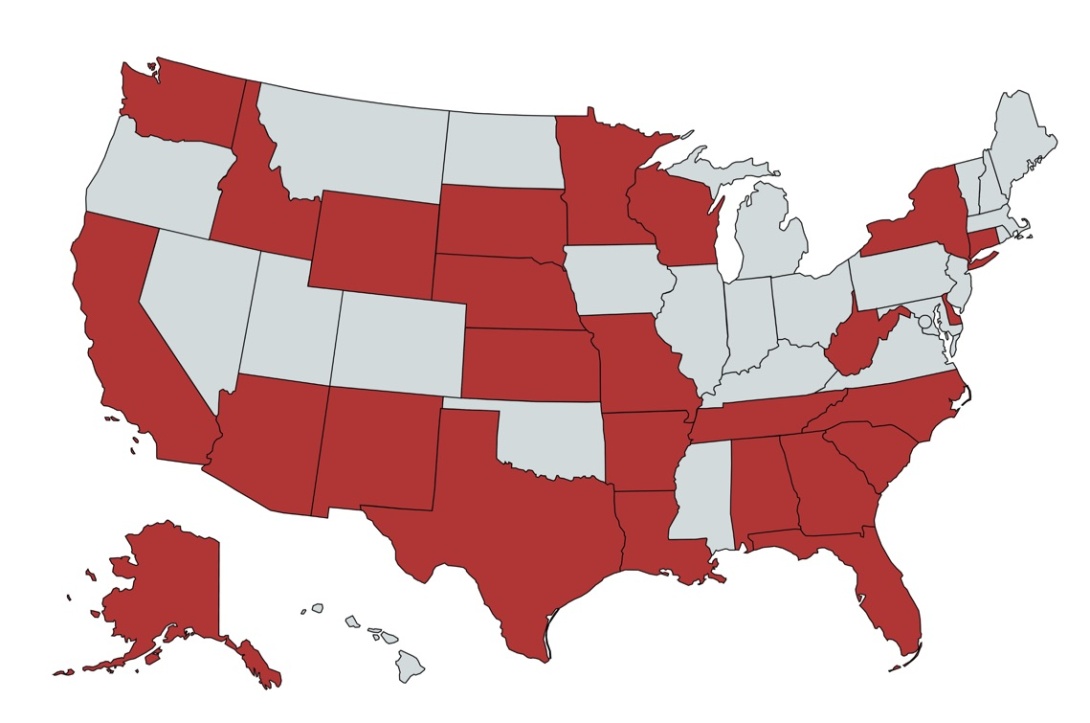

The 26 states shown here in red, including 10 in the South, have laws in place that can block people with felony convictions from regaining their voting rights until all legal financial obligations are met. Unpaid court fees are a major barrier for formerly incarcerated individuals hoping to gain back their right to vote. (Map by Facing South.)

(Update: On Sept. 11, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against giving Florida felons the right to vote regardless of outstanding legal obligations. Julie Ebenstein, senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union's Voting Rights Project, called the decision "an affront to the spirit of democracy.")

Last month Desmond Meade voted for the first time in 30 years, casting a ballot in his home state of Florida. His status as a former felon had prevented him from doing so before under the state's previous felony disenfranchisement laws.

As the executive director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, Meade is the leader of the movement that's changing those laws. As a result of his and others' organizing efforts, in November 2018 nearly two-thirds of Florida voters approved Amendment 4, a ballot measure that restored voting rights to nearly 1.5 million people with past felony convictions. Prior to Amendment 4, Floridians accounted for nearly a quarter of the total U.S. population that was disenfranchised because of previous criminal convictions.

While the participation of Meade and others like him in Florida's 2020 primary is a major victory for the voting rights movement, not all ex-felons are able to vote due to policies in place in Florida and other states that require them to pay all court fines and fees before regaining their voting rights. As Meade said on primary election day. "I'm going to be excited that I'm voting for the first time in over 30 years. But I'm also going to be a little dismayed because I know there are hundreds of thousands of people that wish they could vote, but they won't be able to vote."

In the 2016 election, 6.1 million Americans could not vote because of laws disenfranchising people with past felony convictions. In six Southern states — Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia — more than 7% of the adult population was disenfranchised because of such laws. They also take a disproportionate toll on communities of color: Over 7.4% of the adult African American population in the U.S. was disenfranchised under them in 2016 compared to just 1.8% of the non-African American population.

Since then, voting rights advocates have made important gains in reforming those laws. Over the past four years, 11 states including Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, and Louisiana as well as Washington, D.C., have expanded voting rights for currently and formerly incarcerated people. But 31 states still have some level of felony disenfranchisement that continues even after someone's been released from prison. And of the 17 states that automatically restore voting rights to people with felony convictions upon release from prison, none are in the South, where most states require the completion of prison, parole, and probation.

Many states also require people with felony convictions to pay all of their "legal financial obligations" — fines, fees, and restitution — before getting back their voting rights. Currently, 10 states deny re-enfranchisement indefinitely due to unpaid court fines: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Tennessee, Texas, and South Dakota, according to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative. Another 16 states allow outstanding fees to delay the restoration of voting rights in certain cases; they include the Southern states of Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and West Virginia.

Following the passage of Amendment 4 in Florida, the Republican-controlled legislature passed and Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) signed into law a bill requiring ex-felons to pay all court fees and fines before they can register to vote. Opponents liken this and similar laws to a "poll tax" that unfairly disenfranchises the poor. Such taxes were outlawed in federal elections by the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution adopted in 1964, and two years later in the five Southern states that still used them — Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia — by the Supreme Court ruling in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections.

Florida's controversial pay-to-vote law — which disenfranchises an estimated 770,000 people — is being challenged in the federal courts in Jones v. DeSantis. The case was brought by a coalition of voters who say the law unconstitutionally discriminates on the basis of wealth and violates the 24th Amendment. In May, a federal district court agreed with the plaintiffs. But Florida appealed the decision to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which is now considering the case. The court is expected to reach a decision before Oct. 5, Florida's voter registration deadline.

In North Carolina, meanwhile, a legal challenge to the state's pay-to-vote policies recently resulted in a preliminary injunction that will allow some ex-felons previously barred from voting to do so this November. The lawsuit was filed on behalf of four individual North Carolinians and several community groups that conduct voter registration and education and work directly with people impacted by the criminal legal system. Last week a panel of three state court judges issued a preliminary injunction requiring that North Carolinians who remain on probation or parole simply for failing to pay fines and fees be allowed to vote in November. The litigation is a part of the broader "Unlock Our Vote" campaign, which aims to ensure equal access to the ballot despite a person's criminal record.

"We never ended the racial caste system in the United States; we merely redesigned it, which is a failure of our democratic ideals. The disenfranchisement of citizens on probation, parole, or post-release supervision has been a critical feature of that racial caste system, and it is long past time for it to end so the promise of democracy can be realized for all," said Farbod Faraji, an attorney with Protect Democracy, one of the legal groups involved in bringing the case. "Today, a North Carolina court took a crucial step in the right direction and we look forward to going to trial."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.