Groups across the South are working to fix a broken farm labor system

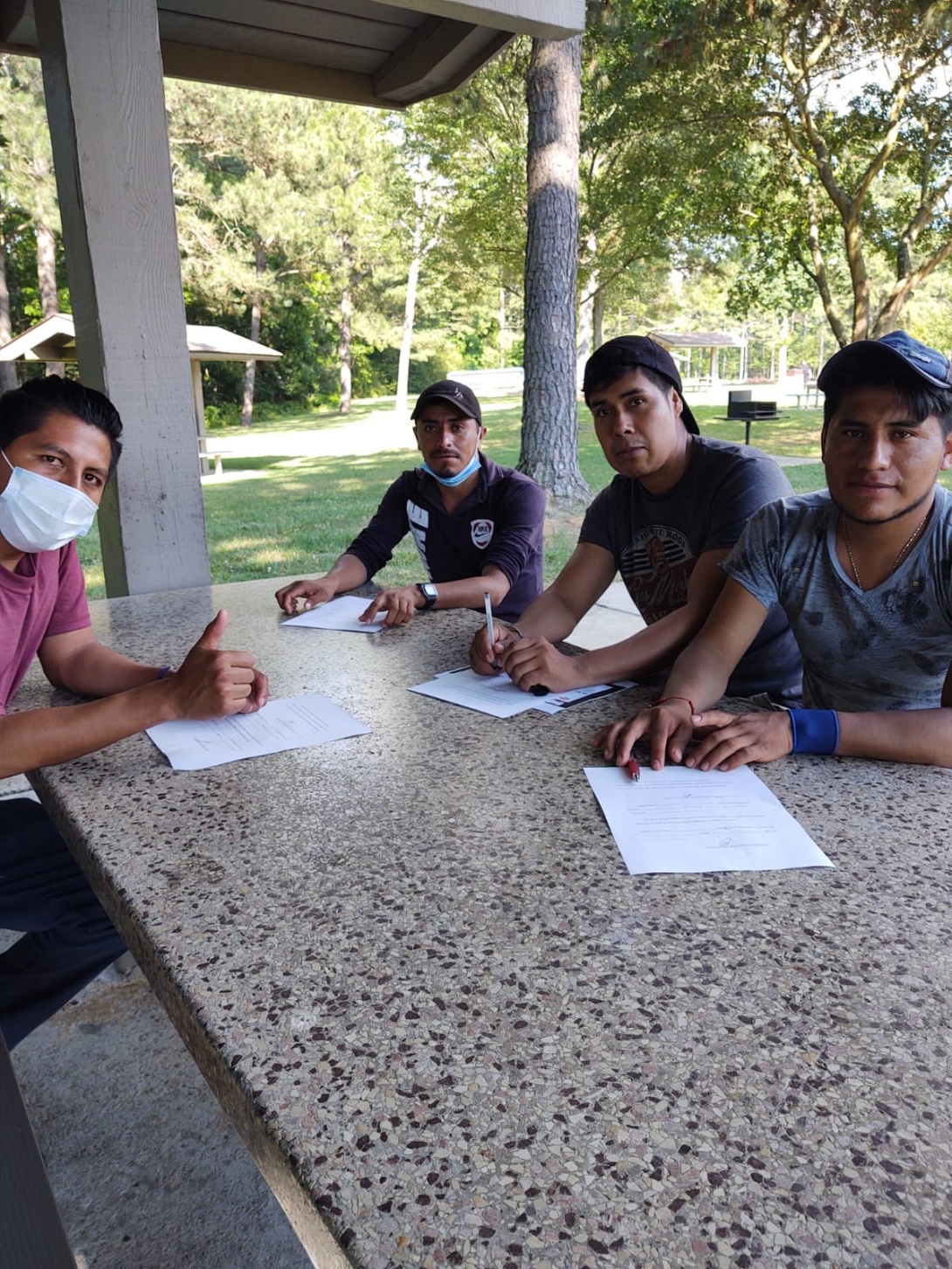

Jorge Bautista Sabino (second from right) came to the U.S. from Mexico on an agricultural visa sponsored by a farm labor contractor. After facing wage theft and other abuses, Sabino joined a class action lawsuit with the support of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee, for whom he now works. (Photo courtesy of FLOC.)

For years, legal organizations and farmworker advocacy groups have sounded the alarm about the H-2A visa program — the most common legal route to hiring foreign agricultural workers. Faced with massive worker shortages, farmers in the South have increasingly turned to foreign laborers, who come to work on temporary employer-sponsored visas.

The program, which ties employees and their visas to the employer, is rife with abuse. Wage theft is rampant, forced labor is common, and the contracts employers sign, which guarantee certain hours and living conditions, are rarely honored. On top of that the U.S. Department of Labor rarely enforces regulations, which allows mistreatment to go unchecked. In 2019, the DOL performed just over 1,000 agricultural wage theft investigations, down from 2,431 in 2000, according to a recent report from the Economic Policy Institute. At the same time, the number of workers on H-2A visas has increased 660%, from 30,000 in 2000 to more than 200,000 in 2019.

Jorge Bautista Sabino was one of those 200,000. Sabino met a recruiter in his Mexican hometown of Tamazunchale who offered him a spot working on farms in Eastern North Carolina. Instead of working on one farm, he'd be working for a farm labor contractor (FLC), who would sponsor his visa, guarantee him a minimum number of work hours, and provide him with housing and food. In exchange, Sabino would work on several farms across Edgecombe County, picking a variety of crops, including tobacco and sweet potatoes.

As countless H-2A workers will attest, the reality was far from what was written in the contract. When he arrived, Sabino was crammed into a dilapidated trailer with nine other men, and barely worked enough hours to pay for his employer-provided meals. "Most of the hours went to people who had been there before," Sabino says. "The newer people barely got any work."

Given the widespread nature of wage violations and the comparatively small number of investigators, farmworkers like Sabino often rely on legal aid organizations to resolve these cases. Southern Migrant Legal Services is one such organization. SMLS operates as a subgroup of Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, a federally funded legal aid organization, and focuses specifically on farmworkers living and working in six Southern states: Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee. While the organization's mandate is broad, the bulk of its work focuses on litigating wage violations on behalf of H-2A workers. Caitlin Berberich, the director of SMLS, says this is because H-2A workers make up the bulk of the farm labor force in the region.

While these lawsuits often result in settlements in favor of the farmworkers, they rarely lead to long-term changes to employers' behavior. Organizations like SMLS that are funded by the Legal Services Corp., a nonprofit established by Congress in 1974, are only allowed to help clients who apply directly for services, limiting their actions to small-scale litigation and assistance with filing complaints with the DOL. These lawsuits tend to result in fairly small settlements, which most employers see as a cost of doing business, according to Greg Schell, a veteran labor lawyer with more than four decades of experience trying wage violation cases involving H-2A workers.

Winning a lawsuit or settlement also doesn't mean that farmworkers will receive the compensation they're owed. The DOL does not release data on how many settlements are paid through — a problem in and of itself. However, Berberich says nonpayment occurs fairly often, especially for workers in crops with particularly small margins. These growers often face solvency issues that prevent them from paying out.

"If you pursue litigation against forestry employers, for example, you might win or get a judgment, but it can often be difficult to collect those wages because they are insolvent," she said.

Additionally, the growth of FLCs has made it even more difficult for workers to collect on settlements. These contractors, many of whom are former farmworkers themselves, are particularly appealing to growers because they offer a layer of insulation against wage theft claims. But they have also emerged as the worst offenders of federal labor laws, according to the EPI. While the DOL can choose to revoke a contractor's license, those same contractors may reestablish operations under another family member, or growers will simply switch to a different contractor.

More than a month into his contract, Sabino's employer in North Carolina still hadn't reimbursed his travel costs. Sabino and his roommates met with a union representative from the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), which sent a letter to the growers and the FLC on their behalf. As a result, the contractor began to increase hours and reimburse travel costs. After the season ended, however, that grower simply declined to work with Sabino and the other workers that had teamed up with the union. So Sabino, along with 200 other workers, filed several class action lawsuits against the growers with the support of FLOC.

Class action lawsuits have become a valuable tool for legal organizations fighting for the rights of H-2A workers. Suits like Sabino's tend to gain national attention and, when settlements are reached, they tend to be fairly large. In Sabino's case, two of the class actions settled for a total of $160,000. Several legal organizations have started to take this approach. In August, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of a group of H-2A sugarcane workers in Louisiana who had been subject to wage theft during the course of their employment.

These cases can also have an impact on policy. Schell points to a case he tried in Florida that resulted in a ruling that H-2A employers must reimburse workers' travel expenses within the first week of the contract. Previously, employers would delay reimbursement until halfway through the contract, which allowed them to fire workers without fulfilling their contractual requirement to pay for travel costs. But such wins are on a state-by-state basis. Sabino, for example, faced a similar situation almost two decades later because North Carolina doesn't require employers to reimburse travel expenses within the first week.

Focusing up the chain

Every expert interviewed for this piece suggested that this whack-a-mole approach was a symptom of a broader, more intractable issue: Farms in the South, most of which are small operations, can't make ends meet if they pay workers a living wage.

"For many of these crops, the business model, frankly, no longer works. In other words, you cannot pay the workers the required wage and make a profit," says Schell.

That's why many farmworker advocacy organizations have turned their focus to companies at the top of the power chain, calling out their role in suppressing prices. These corporations have long insulated themselves from allegations of abuse by contracting to growers, who in turn contract to FLCs. However, it's those companies' demands for lower prices that lead growers to cut corners. Organizations like FLOC and the Florida-based Coalition of Immokalee Workers have traced these abuses up the chain, putting pressure on corporations that buy from the growers as well as the grocery chains that stock the products.

In Sabino's case, FLOC has been encouraging tobacco companies like Philip Morris and Reynolds American that buy from the growers to improve their contracting systems and pay higher rates to growers with good labor practices. The union also helped Sabino sign a contract with a grower covered under the union's collective bargaining contract. These contracts ensure that H-2A workers make a fair wage and are not subject to poor living conditions.

Policy changes that seemed distant under the Trump administration now appear within reach. FLOC is currently lobbying the Biden administration to prosecute growers who knowingly allow H-2A FLCs to commit labor violations, and organizations like the SPLC are also pushing for reforms to the H-2A system. However, most of the demand comes from unions in California, which are primarily concerned with immigration, according to Greg Schell, the farmworkers' rights lawyer. Even though Southern states like Florida hire far more H-2A workers than California, reforms to the program's labor laws are often afterthoughts.

While FLOC has also been working on the policy front, it believes that targeted actions are most effective. "Looking at these corporate supply chains, we've been able to achieve more by getting union agreements through supply chain actions than we've ever been able to achieve in legislative campaigns," says Justin Flores, FLOC's vice president.

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers launched its Fair Food Program in 2011 as a means of regulating conditions on Florida's tomato farms. Like FLOC, the Fair Foods Program works to improve growers' actions by demanding accountability further up the supply chain. Buyers that participate in the program — including major grocery chains like Walmart and Whole Foods — agree to purchase produce only from farms that are in good standing with the program. They also pay an additional penny per pound of tomatoes, which goes toward raising workers' paychecks. Today, around 90% of Florida's tomato farms are members of the program.

When H-2A workers on Fair Foods-certified farms have complaints, they are resolved through an internal system, as opposed to going through the courts. Around 80% of complaints are resolved in under a month — significantly faster than the years-long process of litigation. The program also requires that growers directly employ their workers, which effectively halted the use of FLCs in Florida tomato farming.

"I was a sitting judge for 20 years, and what I can say is this mechanism and the market power behind it is much more effective than the legal system when it comes to transparency and getting quick resolutions," says Laura Safer Espinoza, the executive director of the Fair Food Standards Council, which oversees implementation of the Fair Food Program.

For Sabino, organizing became more than just a way to get what he was owed. When he returned home to Mexico, he found out that many of the workers in his town had experienced abuses under the same contractor. He now works for FLOC, recruiting other workers to join the class action suit.

"It feels good to let people know that they don't have to take that kind of stuff as an H-2A worker," Sabino says. "Workers don't have to just sit back and accept it."

Tags

Jonah Goldman Kay

Jonah Goldman Kay is a journalist based in New Orleans. He writes about art, politics, and the intersection of the two. His work has appeared in The New Republic, Politico, and The Paris Review.