A new day for labor in the South?

Last September, nurses at Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, won a historic union election to represent 1,600 health care workers. (Photo by Christine Rucker.)

On Election Day last year, standing outside of a community college 30 miles outside of downtown Pittsburgh, presidential hopeful Joe Biden pledged to a small crowd that he'd be "the most pro-union president you've ever seen." It wasn't the first or last time Biden would make support for labor a centerpiece of his policy agenda: He launched his White House bid at a union hall in 2019, and in a call with corporate chiefs and labor leaders after the election last November, he flatly stated that "unions are going to have increased power" in his administration.

"I want you to know," Biden told the assembled business and union leaders, "I'm a union guy."

Biden's promises to support unions come at a precarious moment for workers and organized labor, especially in the South. Millions have lost jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, while coronavirus-related health threats have plagued tens of thousands of health care, meatpacking, and other essential workers, underscoring the need for strong safety protections on the job.

In this tumultuous environment, workers have shown signs of increased support for unions, which in unionized workplaces have succeeded in forestalling layoffs and won key health and safety protections. Last September, nurses won a major union drive at Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, affecting 1,600 workers, and next month 6,000 Amazon warehouse employees in Bessemer, Alabama, will vote on whether to form a union, the culmination of a high-profile campaign that has attracted support from players in the National Football League.

Despite signs of growing support for unions, workers face formidable barriers to organizing and winning improvements in workplace standards, especially in Southern states. In his first days in office, President Biden took a number of steps advocated by union leaders, including personnel changes in key agencies and a handful of pro-labor executive orders.

But the real test of the new administration's commitment to labor will come on the legislative front, where Democrats have proposed sweeping reforms to the country's labor laws — measures that grassroots activists agree could transform the climate for workers and unions in the South.

The Southern union landscape

Creating and joining a union has always been more difficult in the South, and recent history has largely been a story of lawmakers and courts erecting new barriers to labor organizing. The Supreme Court's 2018 Janus decision, for example, ruled that public employees don't have to belong to a union to enjoy the benefits of union contracts. Over the last four years, the Trump administration has unleashed a flurry of rules that rolled back overtime pay and narrowed collective bargaining rights, among other anti-labor measures.

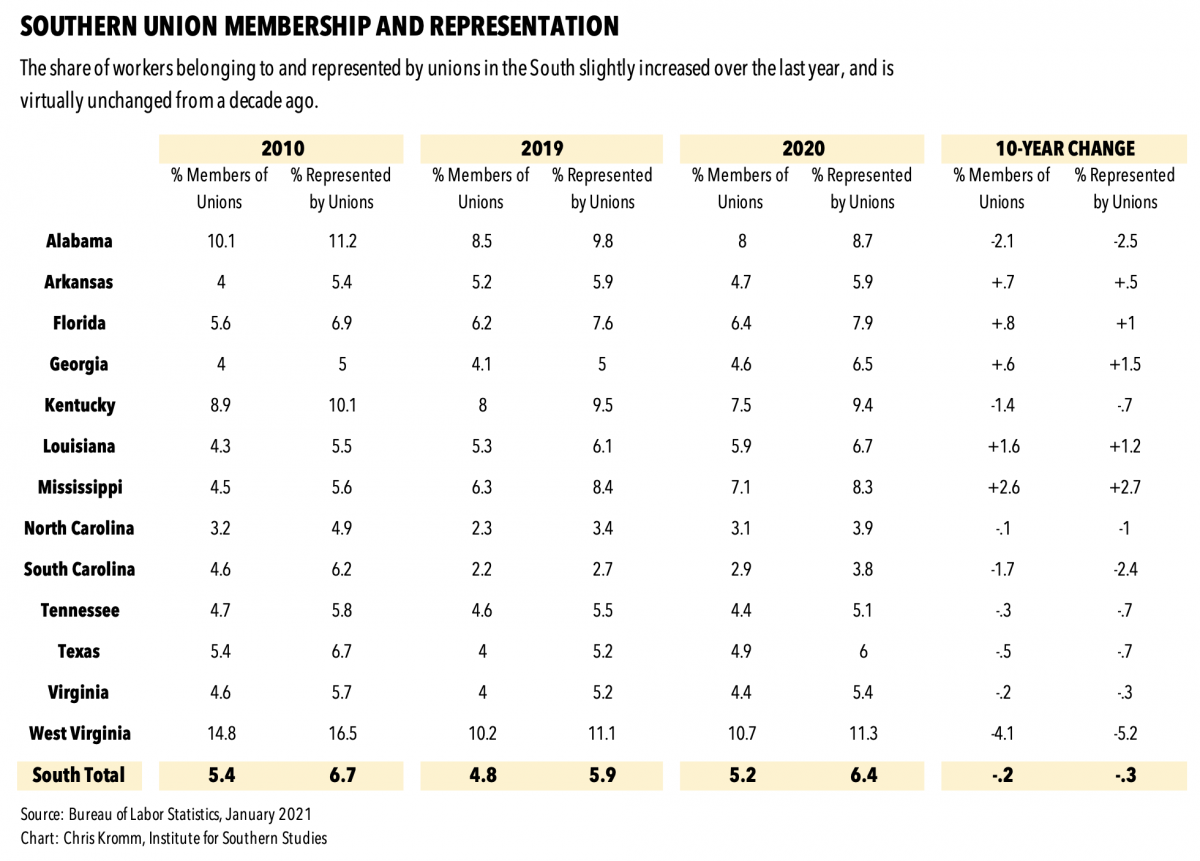

Despite the grim legal and regulatory climate for labor, the share of Southern workers belonging to and represented by unions saw a slight increase over the last year. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data released this month, 5.2 percent of workers in Southern states belonged to a union, a small uptick from the 4.8 percent figure a year ago.

Even more workers in the South are represented by unions, a phenomenon resulting from so-called "right-to-work" laws — anti-union measures implemented in the South beginning in the 1940s that force unions to provide the benefits of union contracts and representation to non-members. Across the 13 Southern states, 6.4 percent of employees are represented by a union, compared to 5.9 percent a year ago. (Click on chart for a larger version.)

The small increase in unionization in the South and nationally over the last year runs against one piece of conventional wisdom about labor: that workers are generally more fearful about joining unions in times of economic uncertainty. As long-time labor reporter Stephen Greenhouse told The Morning Consult last year, "[W]orkers often feel more precarious, their lives are uncertain and those at work might fear that if you speak out and fight for a union, maybe they'll get in trouble."

Labor activist Rich Yeselson agrees. "People feel better about unions when labor markets are tighter and there is less fear of being laid off," he told Vox. In the same report, Jake Rosenfeld, a sociology professor at Washington University in St. Louis, said, "When unemployment spikes, many blame businesses (understandably) but also organized labor. It seems clear that non-union workers look to their unionized peers with resentment during tough economic times (aided by enterprising anti-union politicians)."

The economic woes brought by the COVID-19 pandemic may be different, for two reasons. First, workers may be noticing that employees in unionized workplaces have had better luck pushing for health and safety protections on the job and negotiating better job security in the face of the pandemic. As Rebecca Givan, a professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers University, has noted, "Union members could hold on to their jobs because they can negotiate more creative solutions to economic challenges — furloughs or reductions in hours or even early retirement or other programs to try to avoid mass layoffs."

But the other reason unions have managed incremental gains during the COVID-19 pandemic are less positive for labor: Workers in non-unionized industries like hospitality and leisure have suffered disproportionate job losses, leaving a larger share of those still employed in unionized sectors. A recent analysis by the Economic Policy Institute estimates that about half of the increase in the unionization rate was due to the pandemic's devastating blows to less-unionized industries.

Growing support for labor

Another factor is changing public attitudes about unions. Across the country, support for unions has grown in recent years. A Gallup poll last summer found 65 percent of the public has a favorable view of unions — the highest percentage in 17 years, and on par with levels of public support seen in the 1960s. Approval of unions crosses partisan lines: While support is highest among Democrats at 83 percent, 64 percent of those who identify as independents and 45 percent of Republicans also say they view unions favorably.

The most recent Gallup poll didn't break down attitudes about unions by region, but earlier surveys have suggested that public support for organized labor in the South nearly matched approval ratings in other parts of the country.

In the South, where government and business leaders have often made anti-unionism a political mantra, the language of organized labor itself may play a role in how people view unions. A Morning Consult survey in early 2020 found that approval shot up when pollsters described what unions do, but took out the term "labor union": 77 percent of adults — including 73 percent of Republicans — said they somewhat or strongly support "employees' right to bargain collectively for workplace conditions such as pay, health care and time off."

Union attitudes have also been shaped by high-profile labor campaigns. Researchers found, for example, that the teacher strikes which erupted in 2018 — including large demonstrations in Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia — increased support for labor in those states, including workers going on strike to win improvements in pay and job conditions.

Dismantling the barriers

But increased public support for unions hasn't translated into large-scale gains for labor in the South and nationally, in part due to a daunting array of barriers to joining and maintaining a union. Obstacles to labor organizing only grew during the Trump era, and union activists are tentatively hopeful that the Biden administration is serious about creating a climate less hostile to labor in the South and beyond.

Labor leaders are encouraged by the Biden administration's initial steps. In his first days in office, Biden nominated Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, a former union leader, for labor secretary. He also fired Peter Robb, the notoriously anti-union general counsel for the National Labor Relations Board, and his deputy Alice Stock, after they refused to resign.

"A union-busting lawyer by trade, Robb mounted an unrelenting attack for more than three years on workers' right to organize and engage in collective bargaining," said AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka. "His actions sought to stymie the tens of millions of workers who say they would vote to join a union today and violated the stated purpose of the National Labor Relations Act — to encourage collective bargaining. Robb's removal is the first step toward giving workers a fair shot again."

But the centerpiece of labor's agenda for the Biden administration is the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, a broad-ranging bill that aims to bolster penalties for companies that violate workers' rights while expanding the power of collective bargaining and strengthening workers' ability to form and maintain unions.

One of the most significant pieces of the PRO Act is a federal override of state "right-to-work" laws. In 2017, Kentucky became the 27th state and last in the South to adopt these measures that allow union representation and benefits to employees who don't belong to a union.

"The whole South has right-to-work laws, this is where they originated," MaryBe McMillan, president of the North Carolina AFL-CIO, told Facing South. "It would be a completely different environment here in North Carolina to be able to collect fair share fees from workers who are already represented by a union, so that it's not just union members who are paying but everybody's that's reaping the benefits of a union contract who can put in some money towards the administration and implementation of a contract and union representation."

McMillan is also encouraged by Biden's support for reforms that would allow public employees to collectively bargain, something prohibited in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia, and the PRO Act's heightened penalties and enforcement measures against employers who threaten and even fire workers who attempt to unionize.

"It's really important that companies face stiff penalties when they break the law and violate workers' rights," said McMillan. "That's especially important here in the South, where we see a real hostile, union-busting climate."

Chris Baumann, Southern director for the Workers United unions, agrees that the PRO Act would be "transformative" for the South.

"We know right-to-work came out of Jim Crow laws in the South, that was meant to keep Black and white workers separated, and that legacy continues," Baumann told Facing South. "It's been a way to weaken working class power in the South since its beginning, and it's worked."

Baumann also points to the benefits of Biden's executive orders, including a measure to increase wages for federal contractors to $15 an hour, and his broader legislative goal of boosting the national minimum wage to the same level. "That would have such a huge impact on our members in the South, in terms of their economic well-being," Baumann said. "It would do way more than what we've won in union contract negotiations."

Learning from the Obama years

While the new administration has brought heightened optimism for labor reform, union leaders are still haunted by failure to pass similar measures during president Obama's tenure. In 2008, Obama and other Democrats campaigned on a pro-labor agenda including support for the Employee Free Choice Act, which included similar provisions to protect worker organizing rights. But once in power, Democrats in the White House and Congress deemphasized labor reform, and support for the bill waned.

"I think we learned a lesson from the failure of the Employee Free Choice Act to advance," said McMillan. She notes that in 2020 unions refused to endorse several Democratic candidates who refused to back the PRO Act, and labor has been more proactive in cultivating "labor champions" in the party — and making it clear that failure to support labor reform won't be ignored.

"I'm confident that we won't see the same situation [as 2009]," McMillan said. "But I can tell you that if some people do break their promises to working people, then they're going to get challenged in primaries and there's going to be campaigns against them to hold them accountable."

Passing the PRO Act and other far-reaching labor reforms will likely be a heavy lift. But if the Biden administration and progressive majorities in Congress succeed, Baumann and other labor organizers believe it will allow workers and the public to demonstrate the breadth of support for unions in the South.

"A lot of people want to organize unions in the South," Baumann said. "We have a good success record; we win way more than we lose. But the system is so broken. Biden can free up the system so that democracy can work."

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.