From the Archives: Building a new Southern freedom movement

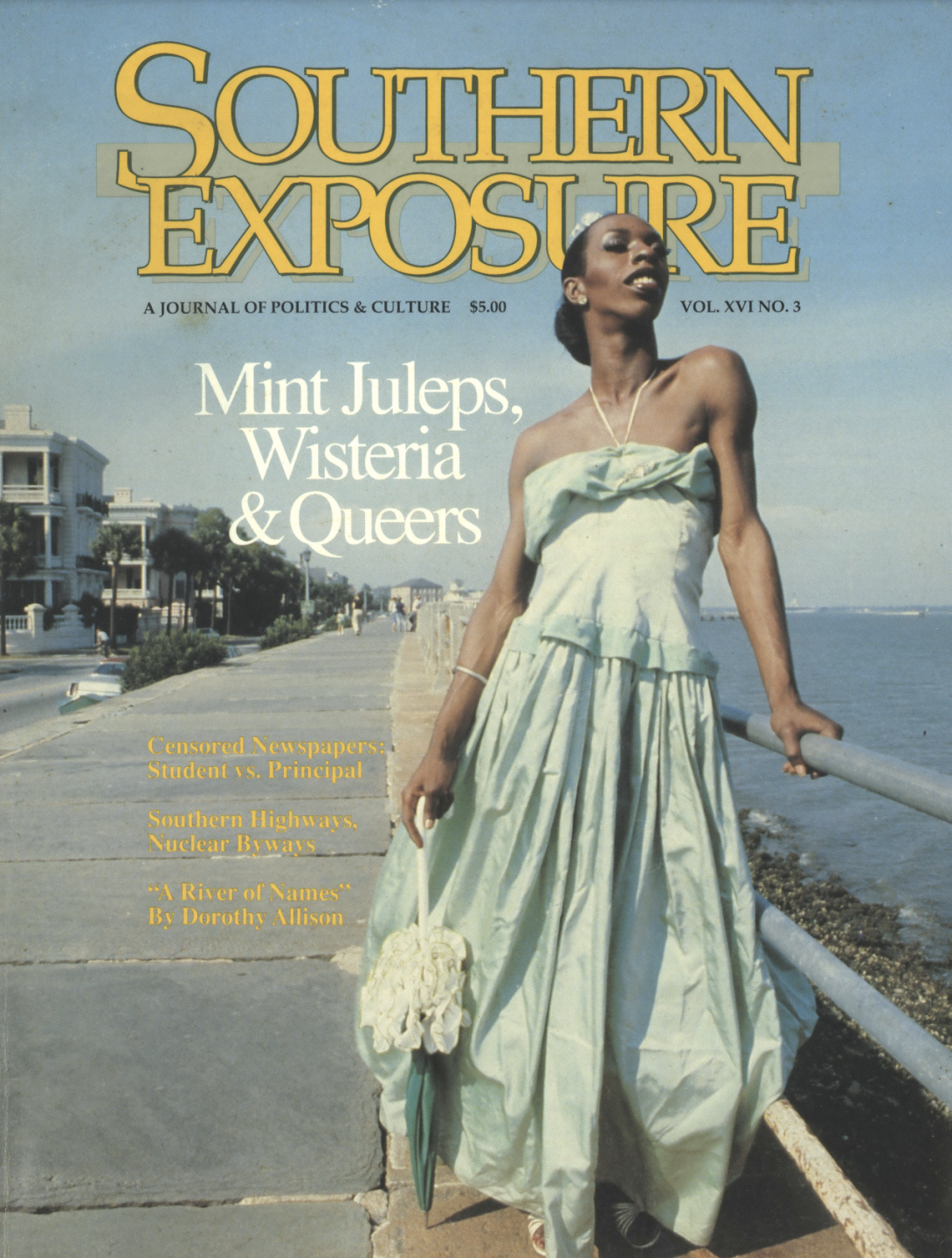

The cover of the fall 1988 issue of Southern Exposure, from which this article is excerpted.

In the spring of 1988, Mab Segrest — then the director of North Carolinians Against Racist and Religious Violence and an activist in the South's lesbian and gay rights movement — delivered the keynote address at the 13th annual Southeastern Conference of Lesbians and Gay Men, held in Atlanta. We reprinted part of that keynote in a 1988 issue of Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South, to which Segrest was a frequent contributor. The issue's cover section, focused on the gay and lesbian South, was titled "Mint Juleps, Wisterias, and Queers."

In an interview with former Facing South intern Grace Abels last summer, Segrest reflected on the historical moment precipitating the keynote address.

"At the Atlanta conference, I was speaking from left to center, arguing for a Southern queer freedom movement," she said in 2020. "The work in 1988 was to create a space that overlapped the Southern freedom movement growing so powerfully out of Black and labor struggles of the 1960s, with the progressive wing of lesbian-feminist and queer organizing."

Since the 1980s, Segrest has continued her leadership and activism in the South's many movements for freedom. She was a co-founder of Southerners on New Ground, an LGBTQ liberation group, and has written four books. She currently lives in Durham, North Carolina, where she remains an activist and organizer. We're republishing her visionary 1988 address in honor of Pride Month.

We Will Do the Hokey Pokey: Building a New Southern Freedom Movement

What I want is a gay and lesbian freedom movement in the South. I'm talking about civil rights, but not just civil rights; about elimination of anti-gay violence and sodomy law repeal, but more than that. I'm talking about Freedom — freedom in our hearts and intellects and imaginations; and in our beds and bushes and kitchen and all the other places we choose to make love; freedom on the streets and in the courts and legislative buildings; freedom with our families and our neighbors; freedom to be who we are and love each other.

The thing about freedom, though, is that you can't just want it for yourself only, or your own kind. Freedom means everybody: not just the men, not just the people with money, not just the white people, not just the Christians, not just the people without AIDS, not just queers, not just any part of us that might be better off than the rest. Freedom means justice.

Justice in this country takes work. The Supreme Court decision in Bowers v. Hardwick [the landmark 1986 ruling that upheld the constitutionality of a Georgia sodomy law criminalizing oral and anal sex in private between consenting adults] spelled it out for us. Our right to love each other physically has nothing to do with the "concept of ordered liberty upon which this country is based." To give us such a right would cast aside "a millennium of moral teaching" and the "legislative authority of the state." Bowers upheld the same Constitution that allowed slavery — another practice with a millennium of historical roots. It is the same Constitution that privileges "free enterprise" and puts profits over people, to all of our detriment. These sodomy laws, because they affect us in every single Southern state, are the place to begin, just as targeting legalized segregation and voting rights was the place the civil rights movement began in the years after World War II.

If we decide that nothing can stop us from changing the sodomy laws in the Southern states, we will have begun — in fact, we have already begun — on an heroic endeavor. If we have a solidly sodomy South to contend with, we also have the example of the Black freedom movement.

A freedom legacy

We grew up and now live in a region that was partially transformed in our lifetime by the courage and grace of Black people, and we have a legacy from them about what the move toward freedom can achieve.

We also have an obligation to that legacy.

Not only in the South, but all across the country, the gay and lesbian movement and the communities which have grown out of it are too constrained by racism — as is the rest of North American culture. No freedom movement that trods some of the same ground as was walked by Harriet Tubman, or Rosa Parks, or Frederick Douglass, or Martin Luther King, can afford racism.

Gay and lesbian communities in the South are concentrated in urban areas — areas that, because of electoral access opened up by the civil rights movement, are the main arenas in the region and country under at least some control of people of color. In those places, we have to increasingly learn to build and earn alliances — and this process will both increasingly challenge us to change the racism within our own movement as well as the general culture and, perhaps, will make more space for lesbians and gay men of color within their communities of color.

In the freedom movement I am speaking of, we will honor the leadership of gay and lesbian people of color; and we will realize our strength lies in our diversity; in the way our 10 percent pops up across all kinds of cultural boundaries. We will make sure that diversity is honored and reflected in our growing numbers.

We have a freedom legacy, then, as Southerners. But we also have the challenge of creating our own indigenous movement as Southern dykes and faggots.

This means that everybody can't move to San Francisco from Durham or Atlanta or Richmond or New Orleans. And everybody can't move to Durham from Pittsboro, or to Atlanta from Brunswick, or to Richmond from Lynchburg, or to New Orleans from Shreveport or Monroe.

Republicans and fundamentalists met the organizing we have done in Durham, North Carolina with alarms that we were trying to make Durham the "San Francisco of the South." While this has a certain appeal, what I want from a Southern freedom movement is not to create more refugee centers but to keep us from being run out of our homes, wherever they are.

So any attempt to organize in the South will need to take into account not only the cities, but the towns and the countryside in which many of us grew up and left. We must learn to tap the deep and secretive veins of queers who still live in these places.

A Southern freedom movement of lesbians and gay men will put issues of sexuality on the front burner, and there they will heat up very fast. As gay historian John D'Emilio points out, to work against sodomy laws and most other forms of our oppression, we have to learn how to talk about sex. My guess is that sex was not the hottest topic of conversation around the dinner tables when many of us were growing up. So we will be teaching and learning a lot.

Put your butt in

We will bring to our movement our own strengths and style, not the least of which is a humor and whimsy informed by camp. One of my favorite memories from last fall's march on Washington was a moment in the circle before the civil disobedience at the Supreme Court began — direct action that was to include a contingent of people with AIDS who did not know if they would receive adequate medical treatment once arrested.

One of the affinity groups led us in a chorus of the "Hokey Pokey," as we all sang loudly, "You put your butt in, you take your butt out, your put your butt in and you shake it all about." It seemed an essentially gay moment, and I wasn't sure some of my straight friends in the anti-Klan movement would have understood.

Our Southern freedom movement will make clear that what straight people have often misunderstood as a pathetic imitation of them is more often than not subversive satire. Our movement will be totally grounded in what we have had to learn as feminists and homosexuals about our bodies — and everybody's bodies — in this North American culture; not the least of which is how to be loose and whimsical in the face of forces of destruction. We will do the Hokey Pokey.

We will learn to take on the Church in the Bible Belt, and not give definitions of morality to religious fanatics, knowing that if God were as mean as they believed, he would have struck them dead long ago (I say "he" because I never met a fundamentalist who thought God is female.)

We will claim our full places in our families of birth, and know that it is a peculiar dynamic of oppression that we are born into the families of our oppressors. This sometimes feels like growing up in the belly of the beast; but the more sure of our own power we become, the more it's like being inside the wooden horse within the walls of Troy and emerging to catch them unaware. Our presence in our birth families challenges our parents and siblings — and children — to change in intimate and immediate and far-reaching ways that do not happen in other movements.

Through these intimate connections, we will refuse to let the bigots "demonize" us. We will increasingly assert our familiarness in a South that is our home.

AIDS has brought our gay and lesbian community fully to the face of death. But, my lesbian sisters and gay brothers, if we can look there calmly and not avert our eyes or flee — if we can keep celebrating, keep loving, keep moving in humor and joy — then truly, nothing can stop us as we carry in our hearts a familiar refrain:

"Oh, freedom/ Oh, freedom/ Oh, freedom over me./ And before I'll be a slave/ I'll be buried in my grave./ Freedom, freedom, freedom over me."

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.