Lawsuit targets HCA's hospital monopoly in Western North Carolina

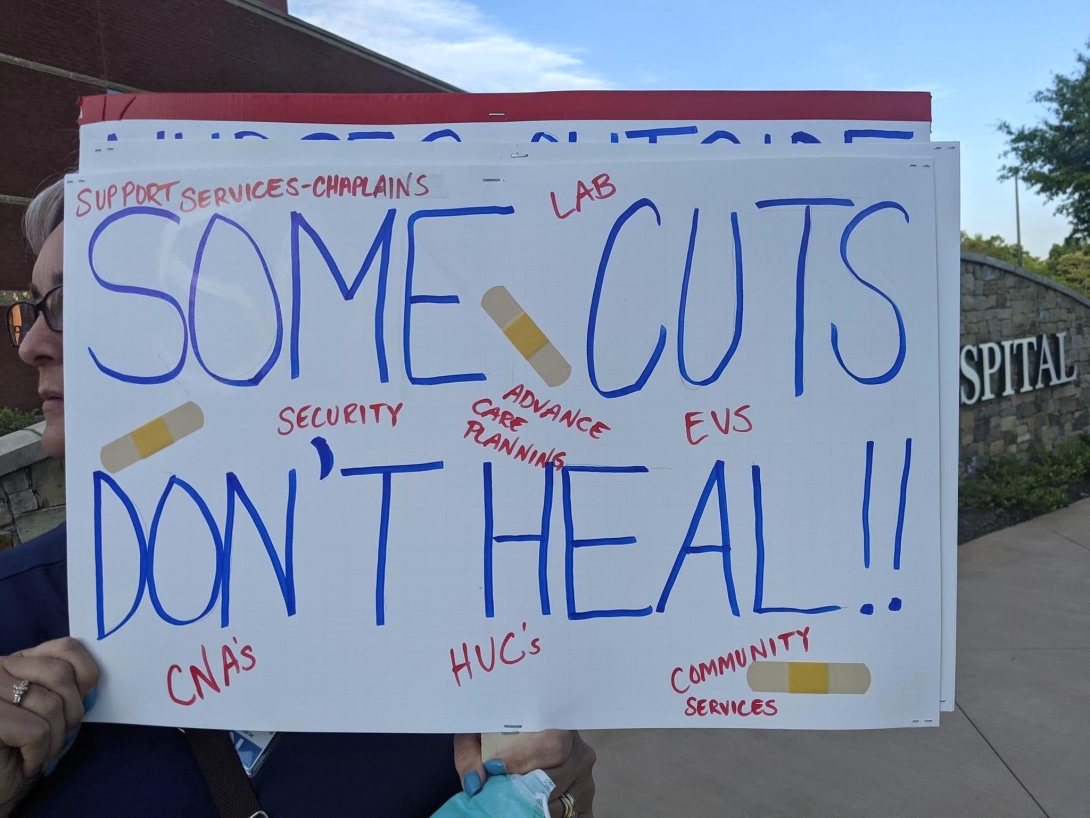

Nurses and concerned local residents held a protest outside Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, in June. HCA Healthcare, the Tennessee-based company that owns the Mission Health system, was hit with a class-action anti-monopoly lawsuit last month. (Photo by Beth Richard.)

Founded as a charity hospital in 1885 and incorporated as a nonprofit in 1951, Mission Health in Asheville, North Carolina, long enjoyed a reputation as a community-oriented hospital system with loyal patients and happy staff. But since going for-profit following its 2019 purchase by Nashville, Tennessee-based HCA Healthcare — a publicly traded hospital operator that's among the most profitable U.S. health care companies — Mission has faced accusations from patients, employees, and public officials that it has sacrificed quality and value of care in pursuit of profits.

Some of the complaints have been documented on Mountain Maladies, a private Facebook group of over 12,000 patients, health care workers, and Western North Carolina residents started last year. They include a patient being told to defecate in the bed because there was not enough staff to help them to the toilet, dramatic jumps in prescription prices, and warnings about unsafe COVID-19 protocols, including a failure to sanitize rooms after infected patients have been intubated.

The growing concerns have led six Western North Carolina residents to sign on to a class-action lawsuit filed against HCA in August for "restraint of trade and unlawful monopolization" in violation of the state constitution and laws. In seven of the 18 counties it serves — Buncombe, Macon, Madison, McDowell, Mitchell, Transylvania, and Yancey — Mission controls between 75% and 91% of the local health care market. The lawsuit says HCA used its dominance in the region to drive up prices while cutting costs in ways that compromise patient and employee health and safety.

The suit was filed in state court on Aug. 10 by Salisbury, North Carolina-based Wallace & Graham — the same firm involved in the successful lawsuits against Smithfield Foods over hog farm pollution in North Carolina — and Fairmark Partners of Washington, D.C. The individual plaintiffs are residents of Buncombe, neighboring Haywood, and nearby Burke counties who had to pay more for health insurance because of HCA's conduct.

"Mission Health was once the crown jewel of North Carolina's health care system," Mona Lisa Wallace of Wallace & Graham said a press statement. "In filing this action, the Plaintiffs seek to have HCA live up to its promises of providing quality affordable health care in Western North Carolina."

J.C. Sadler, vice president of communications for HCA Healthcare's North Carolina division, pointed Facing South to a statement that said the company "will respond appropriately through the legal process."

The 87-page complaint acknowledges that Mission Health has operated as a regional monopoly since buying its last significant competitor, St. Joseph's Hospital in Asheville, in 1995. But it alleges that, since purchasing the system in 2019, HCA has abused Mission Hospital's unique position as the only regional facility providing certain inpatient services like trauma care to compel insurers and patients to pay exorbitant prices or face losing access to those essential services.

One of these so-called "all-or-nothing" practices is known as "tying" or "bundling," when HCA refuses to sell its vital inpatient services at Mission Hospital to insurance companies unless they agree to use its facilities for other, non-essential services. These tactics drive competitors out of business, thereby enabling HCA to raise its prices with impunity.

The lawsuit also alleges that HCA conceals prices from consumers, making it difficult to recognize overbilling. The practice not only fails to comply with a new federal law requiring hospitals to publicize their price lists but disproportionately hurts people with high insurance deductibles or those without insurance. As State Treasurer Dale Folwell told Asheville-based TV station WLOS, "Secret health care costs have a disproportionately negative impact on the upward mobility of lower and fixed income people in western North Carolina."

In just one example from the complaint, which is based on numbers drawn from a RAND analysis, HCA charged over twice as much for a C-section delivery in 2020 — $10,077 — as the average amount allowed by all other state hospitals, $4,373. The nonpartisan Lown Institute Hospitals Index ranked Mission Hospital as the second-worst hospital in the state for ordering unnecessary tests and procedures, giving it a "Value of Care" grade of D minus.

As a result of practices like these, Mission Hospital was the second most profitable out of all 211 of HCA's hospital in 2019, with a net patient revenue of $1.2 billion. It achieved that despite having fewer than half the beds of Houston's Methodist Hospital, HCA's top revenue source at $1.5 billion.

Monopoly's human costs

Wendi Williams, a resident of Asheville for 25 years, knows a bit about medical billing from a brief stint selling health insurance before starting her microbakery, Butterbug's Baked-to-Order. She has also been an inpatient at Mission Hospital and, along with her husband and mother, is a patient in a family practice owned by HCA.

"I've seen things and noticed things in the past two years with their billing that is just astonishing and — in my opinion — predatory," Williams told Facing South.

She recently spent hours on the phone with multiple HCA customer service representatives about a $61.85 bill the family practice sent to her mother. First Williams was told that her mother had not signed the form to release information to her supplemental insurance company. Then she was told that the insurer had denied the claim multiple times. She eventually went to the insurer's online portal and saw it paid the bill two weeks after receiving the initial claim in March 2020 — a full year before the date on the bill that showed up in Williams's mother's mailbox.

"My mother is retired, she's on a set income. She doesn't have extra money to give a multibillion-dollar corporation," said Williams, who emailed HCA a scan of the payment record several weeks ago and is still awaiting a response. "It's like roadblock after roadblock to wear people down so they just pay the bill."

Another consequence of HCA's purchase of Mission Hospital in Asheville has been the closure of HCA/Mission-owned clinics and hospital wards in neighboring counties. Residents in these more rural areas shared their experiences since the buyout in public meetings in January and February 2020 held by the independent monitor responsible for ensuring HCA upheld 15 community commitments it agreed to follow as a prerequisite of acquiring Mission Health.

One speaker from the rural community of Cashiers, North Carolina, objected to HCA replacing their full-time doctor with a travel physician from Atlanta. "[He] was here two days per week … now that's been reduced to two days every other week," the speaker said. "So we have a doctor four days a month." Another speaker who self-identified as an employee at a non-HCA primary care provider in Transylvania County spoke about how staff reductions and unit closures at Mission's Transylvania Regional Hospital in Brevard affected the speed of crucial procedures. "I had a stat radiology that I needed done stat," the speaker said. "Five days, it took me to schedule it."

Staffing cuts have also damaged morale within facilities and were among the factors that led registered nurses at Mission Hospital to vote last September to join the National Nurses Union. They approved their first union contract in July. In addition to guaranteeing pay raises, it requires the hospital to form a committee made up of a dozen union nurses who will review patient care conditions and suggest improvements.

But others aren't sticking around to try to make things better. Honored as one of Mission Health's Great 100 Nurses in 2020, Haley Ramsey posted her letter of resignation on Mountain Maladies after 20 years working at Mission Hospital, most recently in the Mother-Baby Unit. "To experience a nonprofit hospital being taken over by an enormous money-making corporation has been devastating," she wrote, citing understaffing and unsanitary conditions due to cuts in nursing assistant and custodial staff.

"I am no longer willing to put my license, my reputation, or my physical and mental health on the line for a company that does not care about [its] employees or the community it claims to serve," she concluded.

Scrutiny of health care monopolies

Mission Health's current monopoly in the region can be traced back to the North Carolina legislature's passage of a Certificate of Public Advantage (COPA) law as part of the Hospital Cooperation Act of 1993.

A COPA is a legal mechanism that allows a merger between competing hospitals to avoid federal antitrust scrutiny as long as the state determines that its benefits outweigh drawbacks and agrees to step in as a regulator. Today a total of 18 states have COPA laws, including the Southern states of Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; five other states nationwide had them but have since repealed them.

In the 23 years that North Carolina's COPA law was in effect, Mission Hospital was the state's only facility to apply for its protection. In fact, the legislature specifically amended the law in 1995 to enable Mission to purchase St. Joseph's. In exchange for being allowed to operate as a monopoly, Mission agreed to caps on its profit margins, in- and outpatient costs, and the number of local primary physicians it employed. Mission subsequently acquired five other hospitals in the region, bolstering its share of the market.

Then in September 2015, after sustained lobbying by Mission, the legislature repealed the state's COPA law. State oversight ended a year later.

One of the first consequences of the repeal came in June 2017, when Mission terminated its contract with Blue Cross Blue Shield NC, the region's largest health insurance provider, after negotiations between the two companies broke down. Although the gap in coverage for Blue Cross customers lasted only two months before the companies struck a deal, Mission proved it could demand higher prices for its services — prices ultimately passed down to the insurer's North Carolina policyholders. Then in 2019 came Mission's sale to HCA; the COPA terms had previously barred it from being sold to a for-profit system.

The lawsuit against HCA comes as scrutiny of health care monopolies is on the rise nationwide. In 2017, the Federal Trade Commission began an investigation into the effect of COPAs in Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia on health care prices and access; it expanded the scope of that investigation in 2019 and will release its findings in the future. Last year, in addition, the FTC investigated numerous transactions involving hospitals, and there are reports that the U.S. Department of Justice is considering bringing suit over Minnesota-based health insurer UnitedHealth's $8 billion merger with Change Healthcare, a health care analytics and technology vendor based in Nashville, Tennessee.

North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein's office collaborated with the USDOJ in 2016 to file an antitrust complaint against Charlotte-based Atrium Health, formerly Carolinas HealthCare System, to block it from using all-or-nothing practices to acquire a 50% market share in the Charlotte area. Since no purchases had been made, the 2018 settlement simply restricted Atrium's actions in the future.

Facing South reached out to Stein's office about the HCA lawsuit but did not get a response. In a statement provided to WLOS, he said his office is reviewing the lawsuit and "will continue to watch this closely." He also stressed that his office's oversight of the 2019 sale of Mission to HCA did not extend to quality and value of care.

Of the class-action lawsuits against health care providers that have been filed in recent years, most target the practice of "surprise billing," or charging patients for out-of-network services at an in-network facility. HCA, in fact, settled a case in Florida that alleged it overbilled car insurance policyholders for post-accident X-rays and CAT scans; that suit was settled for $220 million in 2018. In July 2020, Tennessee-based Envision Healthcare settled out of court for charging patients out-of-network prices for anesthesia services provided at their in-network hospitals.

A suit out of California that was resolved earlier this year offers insight into what could happen if the HCA suit succeeds. In March, Sacramento-based Sutter Health settled with the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union and state Attorney General Xavier Becerra — now secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services — for $575 million. Accused of overcharging Northern Californians as much as double for certain procedures as Southern Californians, the company agreed to increased transparency, regulatory oversight, and an end to all-or-nothing and tying practices.

Tags

Sara Murphy

Sara Murphy, Ph.D., is a freelance writer living in the mountains outside Asheville, North Carolina. Her work has appeared in Lifehacker, 100 Days in Appalachia, Supermajority News, and Folks.