VOICES: Why school paddling is legal child abuse

"I am Lazarus, come back from the dead

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all"

— from The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T.S. Eliot

Editor's note: This story contains graphic descriptions and images of child abuse.

I first became acquainted with school corporal punishment my first week at Fitzhugh Lee Elementary in Smyrna, Georgia. Out of nowhere, the principal charged into our classroom at a run and yanked a boy near me out of his seat, dangling him in the air with one arm while beating him viciously with a wooden paddle as we watched in horror. It seemed to go on for an eternity: the sounds of the blows, the man panting and seemingly crazed, the boy screaming and crying hysterically. I tried to shout "stop" but no words came out — something that led to a persistent feeling of shame that years later I'd recognize as survivor's guilt. After the principal left, I turned around to give the boy a look of fervent sympathy. Tear-streaked and humiliated, he stuck his tongue out at me.

Many decades later I called my boyfriend from the first and second grade, who had become a long-haul trucker. Elated to reconnect, we decided to visit Fitzhugh Lee Elementary (named after a Confederate general) on the weekend, when no one was there. Holding hands, we peered through the blinds of our squat little classroom, which still exuded a faint prison-like chill and the memory of our after-lunch ritual, in which the teacher would draw the blinds, ask us to stand in a circle and call certain students forward to receive swats with a ping pong-like Bolo Bouncer paddle — for what, I was never sure.

Back then, there was no way to be certain of escaping punishment because no one was ever told what they had done. Standing there with my heart pounding, I often felt a sensation of leaving my body and floating up to the ceiling. There was a rumor that the principal, who was universally hated, had an electric chair in his office for "really bad kids." Reminded of that, my first grade sweetheart, who I'll call Ashley, laughed and shook his head. "God, what an awful place!" he marveled. I told him that it wasn't until third grade, when my family moved to a different county and I entered a warm, inviting public school where corporal punishment was prohibited, that I felt I could breathe again. Ashley, in contrast, had stayed at Fitzhugh Lee, and he told me that on one occasion, he was so covered with bruises after a beating that his father, a race car driver, came to the school and threatened to flatten the principal with his own paddle if he ever touched his boy again.

Every other Western country in the world has banned the practice, but as of today, corporal punishment in public schools is still legal in 19 states, with Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas accounting for the largest percentage. Boys, African Americans and disabled students are most likely to be beaten. The lack of a federal or court ban means school districts are free to allow their personnel to deliberately inflict pain on schoolkids as a means of discipline, starting in preschool. Among private schools, the practice is still legal in 48 states.

If you've never witnessed or experienced a school paddling (read: beating), it may be hard to understand how terrifying they are to a child. A 2016 study of school corporal punishment in Social Policy Report observed that at least one state specified the paddle be 24 inches long — making it half the size of some of the children being struck. "In any other context, the act of an adult hitting another person with a board this size (or really, of any size) would be considered assault with a weapon and would be punishable under criminal law," the authors wrote.

Why, then, are U.S. public school teachers and principals allowed to beat children as young as three with wooden paddles?

There are too many answers to cover everything here. But on the legal front, it is because the US Supreme Court ruled in its 1977 Ingraham v. Wright decision that school corporal punishment is constitutional, allowing states to decide whether to use it. Justice Thurgood Marshall and three other justices dissented vigorously, noting that if the US military and prison guards cannot use corporal punishment on soldiers and prisoners, school personnel should not be allowed to hit students.

Yet in 2017-2018, the last period before widespread distance learning, more than 70,000 public school students in the United States, including 851 preschoolers, were hit by teachers or principals, according to data released by the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights. This number counts only the students hit, not the number of paddlings — by all accounts, many students have been paddled repeatedly. The official number is still a large drop from the 163,333 reported in 2011-2012. But school districts have long underreported their use of harsh punishments like restraints and seclusion, so experts believe the number of school paddlings and other corporal punishment is far greater.

Discussing the corporal punishment of disabled students, for example, the ACLU has noted that "there is no mandated reporting for many types of corporal punishment that take place," such as "throwing children to the floor " or putting them in chokeholds. In addition, many teachers and coaches fail to report their paddlings, according to investigations by Human Rights Watch, with one Mississippi teacher telling the organization, "I know that there are paddlings that aren't reported…I'm sure if you ask teachers, they wouldn't be able to tell you how many students they paddled at the end of the day. " "Unofficial" paddlings — like the swat circles at Fitzhugh Lee when I was a child or the sadistic teachers who roam classes with a paddle, hitting kids who drop a pencil or look up from their work — are not even counted. And as I can attest, the terror of witnessing or even knowing a child is being paddled extends the impact beyond the targeted victim; you can multiply the harm done with every paddling or swat by 20 or 40, depending on how many children are in the class.

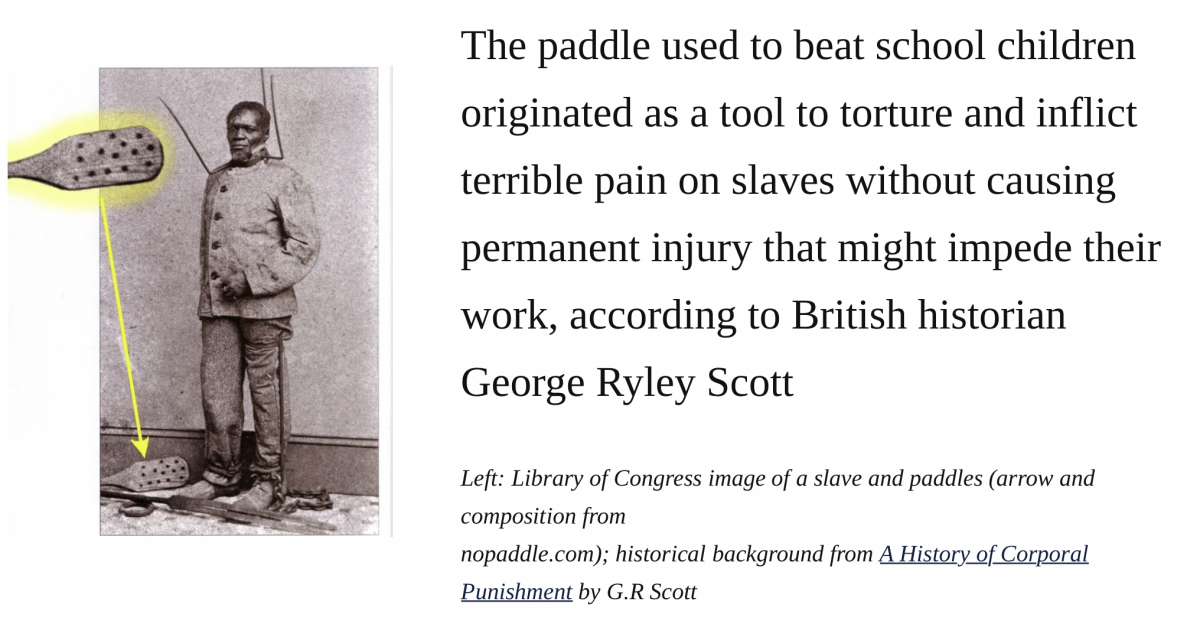

In addition, every organization concerned about racial equity should be up in arms about school paddlings. Black children are beaten more often and disproportionately to the population, according to federal data, leading some African Americans to compare the practice to the floggings inflicted on slaves. The Social Policy Report study showed that in Alabama and Mississipi, African American children are at least 51% more likely to be hit at school than white children in half the school districts, and in a fifth of the districts, they were five times more likely to receive corporal punishment. Nationwide, Black girls are three times more likely to be hit than white girls; Black boys are hit at nearly twice the rate as white boys. Disabled students are also more likely to be punished with violence, according to a 2019 report by the NAACP and the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA, which calls for a ban on "this dangerous and discriminatory practice."

Another memory floats back from the past: Several kids poking me on the Fitzhugh Lee playground in first grade while tears ran down my face. They weren't mean, really, just intensely curious: "Cain'tcha talk, huh? Cain'tcha, huh?" I didn't say anything. I had stopped talking at school on my first day there, which seemed like the safest thing to do. Plus, I had never been around children my age and didn't know how to interact with them. Suddenly a small, wiry boy charged my tormentors and scattered them, jeering "yeah, run away, ya bullies" as they raced off. "Anytime they bother you, you just call me," Ashley said, tapping himself proudly on the chest. "And hey, I bet you can talk but you don't want to, right?" I nodded and he was thrilled. "See, I knew you could! And I knew you was smart; I been watching ya. You're worried about the paddle, ain'tcha?" I nodded again, and we smiled at each other. "Okay, well, you can be my girlfriend — if you want to," he added hastily. "Yeah? Okay, great."

Fast forward 20 years or so. I had left Georgia for college and now was working as a journalist in California. I assumed school beatings had gone the way of segregation, Jim Crow laws and other vestiges of an ugly past. But then I ran across a small clip about a school paddling, like news of a distant battle when you think the war is over. To my dismay, I learned that corporal punishment at school was still legal in 40 states.

My colleague Rob Waters (now founding editor of MindSite News) and I decided to do a nationwide investigation and were sent across the country in the late 1980s by a Time Inc. magazine to cover the ramifications of school paddling. During our four-month investigation of federal and state data, hospital records, and in-person interviews in eight states, we found that hundreds of thousands of children from 5 to 18 were being whipped, spanked, beaten and paddled on the buttocks for reasons that included talking, "sassing," drawing, getting a bad grade, not turning in homework, dropping a pencil or turning around in their seat. In rare cases reported in newspapers, students were struck with baseball bats, tied to chairs or stung with electric cattle prods.

To make matters worse, the paddlings were often accompanied by verbal abuse. "The teacher told us, ‘You welfare kids, you little b's, you're gonna do battle with Mr. Paddle!'" a sweet-faced first-grader from a low-income district in Houston told me. When we asked her what "b's" meant, she looked abashed and finally whispered in my ear: "b-i-t-c-h-e-s."

Jimmy Dunne, a former teacher and anti-paddling activist in Houston, said he doubted many people knew how severe paddlings really were. "I mean, we've got teachers in East Texas who shave down baseball bats and swing with both hands," he told us. Paddlings were sometimes so severe that parents took their children to emergency rooms. (The plaintiff in the Ingraham case ended up there after being held down by school personnel and hit 20 times with a wooden board.) Hospital and medical records we gathered from around the country showed not only welts and bruises but also broken bones, gashes, sprains and concussions.

Meanwhile, the damage to children's minds and spirits was disturbingly evident. Students told us of the terror they felt in the presence of teachers and principals who had hurt them; others were haunted by the pain and guilt they felt at hearing other students scream and beg for mercy. Charlotte Ross, then the director of a youth suicide prevention center in Burlingame, California and now retired, told us, "Schools are saying they want to encourage students' self-confidence, then they undo everything with this violence."

Several parents recounted to us the damage done by school paddlings to their children, which included teens dropping out of school, long-term depression, recurring nightmares, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some were so traumatized after being hit repeatedly at school that they became severely depressed and suicidal. Among them was a Latino boy in Galveston, Texas, whose father told us his son had become despondent after being paddled repeatedly in the first through third grades. "He's talked about suicide a lot of times, about running in front of a school bus or running onto the freeway to get away from everything," he said. The parents of a third grader paddled in Crosby, Texas, told us he had made elaborate plans to shoot himself with the family rifle — "for weeks, that's all I could think about," their son agreed — but was foiled when he couldn't unlock the cabinet that held the ammunition.

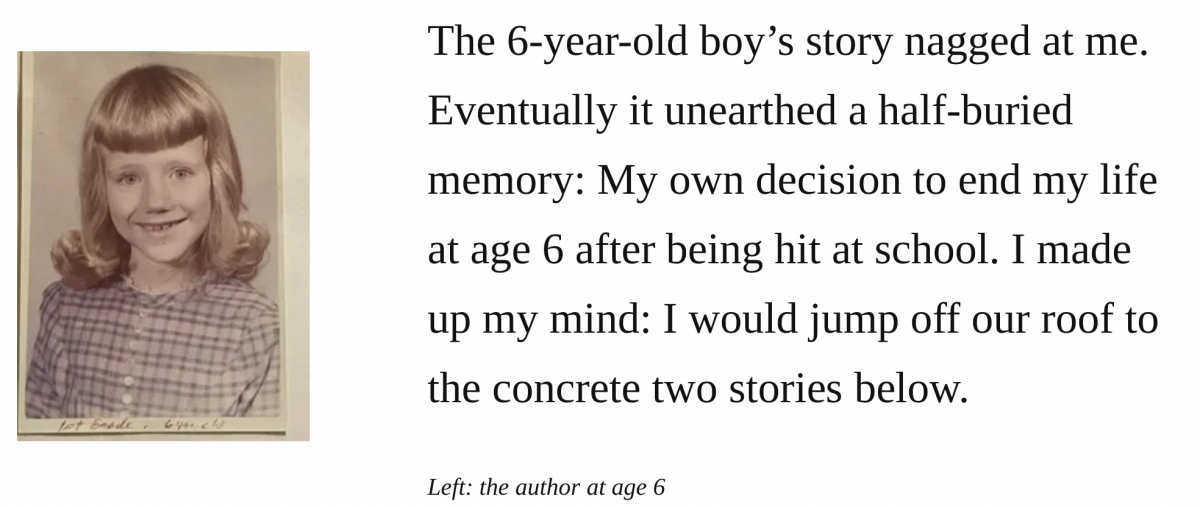

Another suicidal boy I wrote about was a six-year-old with ADHD in Madison, Tennessee, who tried to hang himself after being paddled more than 16 times for talking, "drawing at the wrong time," and other infractions. Standing on the platform of a 10-foot circular slide on the school playground, he tied a jump-rope to the top rail, knotted the rope around his neck and jumped. "I was real scared then and trying to scream for help," he told me over the phone. "The rope was smooshing all the air out of me. I could see all the kids underneath me, circling and circling like lions in a cage. My friends were trying to push me back up, and it seemed like it took forever for a teacher to get over to me." His parents were convinced he didn't want to die. "It was a cry for help," his mother said tearfully, "so we would finally listen when he talked about school."

The story, along with the Tennessee mother's words about listening, nagged at me, eventually unearthing a half-buried memory: My own decision, at age 6, to end my life. It was set in motion, ironically, when I found myself at the head of the line for our class, ready to lead everyone back in from the playground — a role so thrilling and unexpected that I was literally paralyzed with excitement. My teacher turned and gave me a hard swat to get me moving. It was the first and only time I was hit at school, but I was so stunned and mortified that I felt my life was over.

Why? It's hard to imagine from an adult perspective, but at 6 I felt being slapped at school had demoted me to the status of a "bad kid," who would now be looked upon with profound disappointment and regret by her loving and largely religious family. My father had put a ladder up to the gutter to clean out some leaves, so I decided I would climb up on the roof and dive off the back side of the house to the concrete two stories below. Fortunately, the ladder was not there when I got home from school. I decided to wait until it was back to put my plan into action, but my mother noticed something was wrong and asked me why I was so quiet and forlorn. She listened while I told her what had happened at school, then hugged me and told me not to worry about it. Immediately, an enormous weight lifted off me and my plan evaporated.

But who is listening to children now? For years, every leading child and youth welfare organization, health and medical association including the AMA, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and American psychological and psychiatric associations — have demanded that corporal punishment in the schools be abolished. Human Rights Watch and the World Health Organization report that such punishment encourages violence — including domestic violence — and may violate U.S. obligations under the UN Convention Against Torture. Yet some leaders in trauma and healing advocacy have never heard of it. Several have told me they were unaware that school paddling even exists, which makes sense; after all, there are large swatches of the country in which a teacher or principal hitting a child with a wooden board would be promptly arrested.

This awareness gap can be seen in the position statements of many organizations devoted to children's social and emotional learning and healing from adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which, in the absence of support, are linked to a higher lifetime risk of conditions such as cancer, heart and liver disease, substance use and suicide. I believe paddling and all other corporal punishment at school and home should be considered an ACE. But although these organizations exhort parents and schools to provide caring, trusting relationships and rid schools of traumatizing expulsions and active shooter drills, not one position statement I've seen refers to the continued use of school corporal punishment in 19 states — a practice that traumatizes and retraumatizes students each year.

And what accounts for the radio silence on the part of the U.S. Department of Education? In recent years the department appears to have been ignoring the issue, omitting it from its publications and outreach. A 2014 report from the department, "Nondiscriminatory Administration of School Discipline," included no data on corporal punishment. Neither did a 2015 report released by the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights (OCR). — something the authors of the Social Policy Report article found surprising, given that OCR has been collecting data on corporal punishment since 1968 with the goal of enforcing civil rights in public education.

It may seem as though I despise the perpetrators of this violence, but I don't. (Ok, maybe a certain long-departed principal in Georgia). Many of them doubtless experienced the same abuse when they were children and — without receiving any help for the pain and rage they felt — are under the unconscious compulsion to repeat what was done to them, as psychologist Alice Miller would say. Others simply need more training in effective, nonviolent discipline. I've interviewed principals and teachers in Texas and Georgia who told me they hated using the paddle but saw no other way to control their students.

Still others had no idea how destructive their brand of "discipline" is. In Houston years back, I asked one teacher who used the paddle extensively what he would like his students to remember about him. "Just that, he's a good man who taught me a lot," he said earnestly. I told him I was sorry to tell him this, but his students said they hated him, that he hurt them, and they hated school because of him. He turned white, stammering that if they needed to feel that way, so be it. He and other teachers like him need help giving up the paddle — that is, they need a federal or state law that prohibits using it, along with training in ACEs science, trauma, and better, more effective ways to discipline their students so they can become the educators they want to be.

Meanwhile, the abuse of students continues. In 2014, a federal district court refused to hear a lawsuit brought by an 8th grader in Mississippi who fainted after being paddled by a school administrator, falling head first to the floor and breaking his jaw and five of his teeth, according to court papers reviewed by Education Week.

In 2018, a school gave Wylie Greer, 17, of Greenbrier, Arkansas, two swats with a paddle for leaving class to protest a rash of deadly school shootings. Greer told CNN he was given a choice between a suspension and corporal punishment. "I felt like if I stood up and took the punishment in an honorable way it was better than doing what they wanted me to do, which was to shut up and go on with our lives," he said. "The idea that violence should be used against someone who was protesting violence as a means to discipline them is appalling."

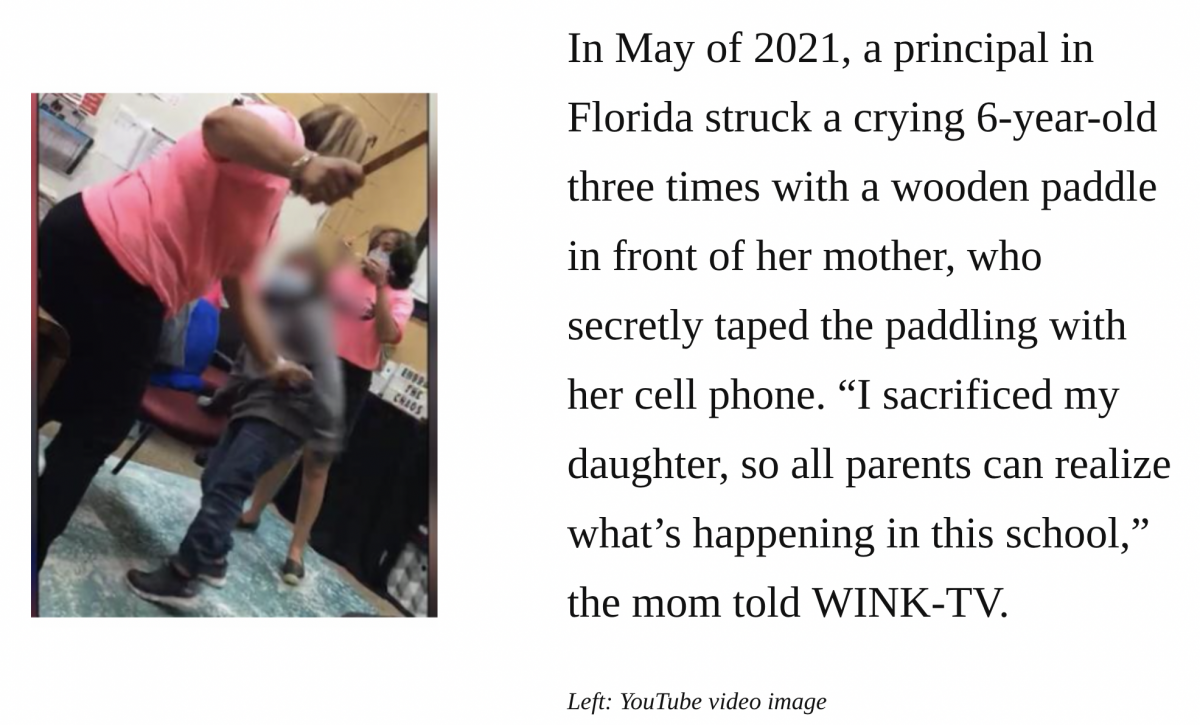

And in May of 2021, in a Florida school district that prohibits corporal punishment of students (emphasis mine), a school principal struck a 6-year-old girl three times with a wooden paddle in front of her mother, who secretly taped the paddling with her cell phone. The girl's alleged infraction: breaking a computer screen. The mother filed a police report against the school, which claimed she had asked the school for help disciplining her daughter. Responding to the outcry, Deputy Chief Assistant State Attorney Abraham R. Thornburg declared that no crime had been committed — another fatuous statement making the world safer for child abuse. (Click here to see a video of the paddling, but be aware it contains disturbing images.)

However, there is hope for change, since a group of House congressional representatives introduced a bill in June of last year, US HR3836, that would ban corporal punishment in the schools. The bill is now in committee.

I used to feel cheated that first grade hurt me and my classmates so badly that it almost ended my life. But now I realize that I have a rare privilege: I am a witness. Teachers, parents, mental health professionals, and policymakers concerned about childhood trauma and healing would do well to set their sights on ridding the United States of school paddlings, a practice better suited to the Middle Ages than any school in this millennium. For the sake of our children and future generations, the federal government should abolish this unconscionable form of child abuse.

(This story originally appeared at MindSite News.)

Tags

Diana Hembree

Diana Hembree is an award-winning health and science journalist, a former senior editor at Time Inc., and the founding co-editor of MindSiteNews, a nonprofit outlet that covers mental health. She is a native of Georgia.