From the Archives: Dumping on Warren County

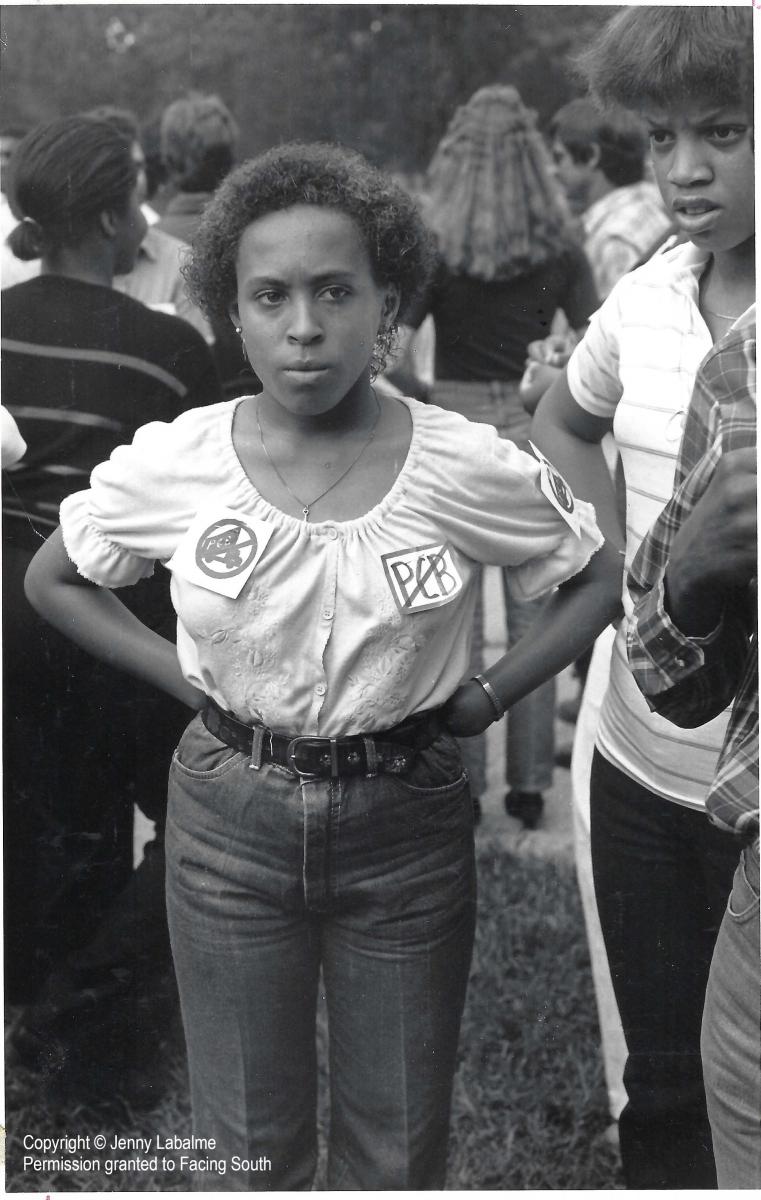

Marchers protested toxic waste dumping in Warren County, North Carolina, in 1982. (Photo copyright Jenny Labalme, used with permission. Do not reproduce.)

This month marks the 40th anniversary of a beginning of the environmental justice movement: the protests over North Carolina's plans to dump toxic waste in a majority-Black rural county in 1982.

Jenny Labalme was on the ground in Warren County as an undergraduate student at Duke, photographing and reporting on citizen organizing against the landfill. In 1988, the Institute for Southern Studies published a book, "Environmental Politics: Lessons from the Grassroots," featuring 10 case studies of environmental organizing across the state of North Carolina. Warren County's fight against the PCB dump was the book's third chapter, with text and photographs by Labalme. Her photos of the nonviolent protests have become some of their most enduring images.

"As soon as I went up to Warren County, that first day, I was moved to my core. I knew what they were doing was important. Of course, I had no journalistic chops then, but you know in your gut — it was just a gut feeling," Labalme told me.

The grassroots nature of the movement comes through in her writing about the struggle and in the images she captured.

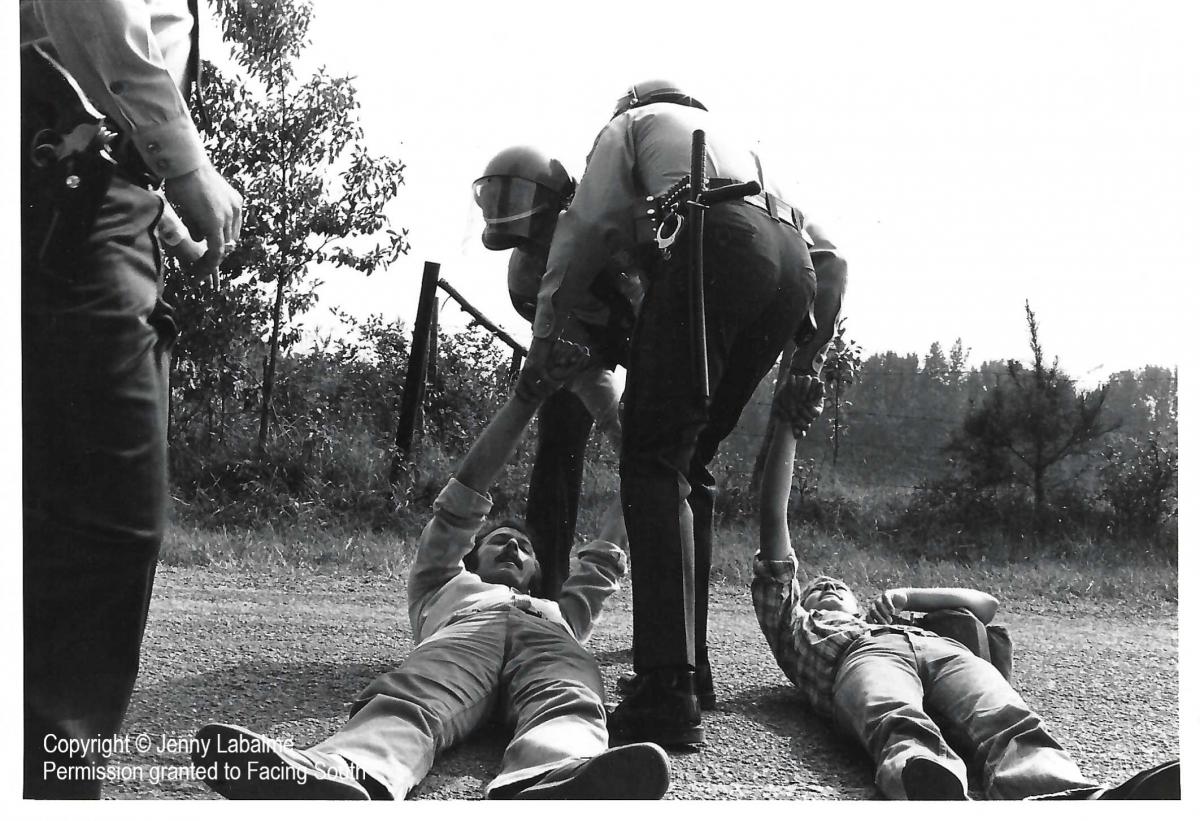

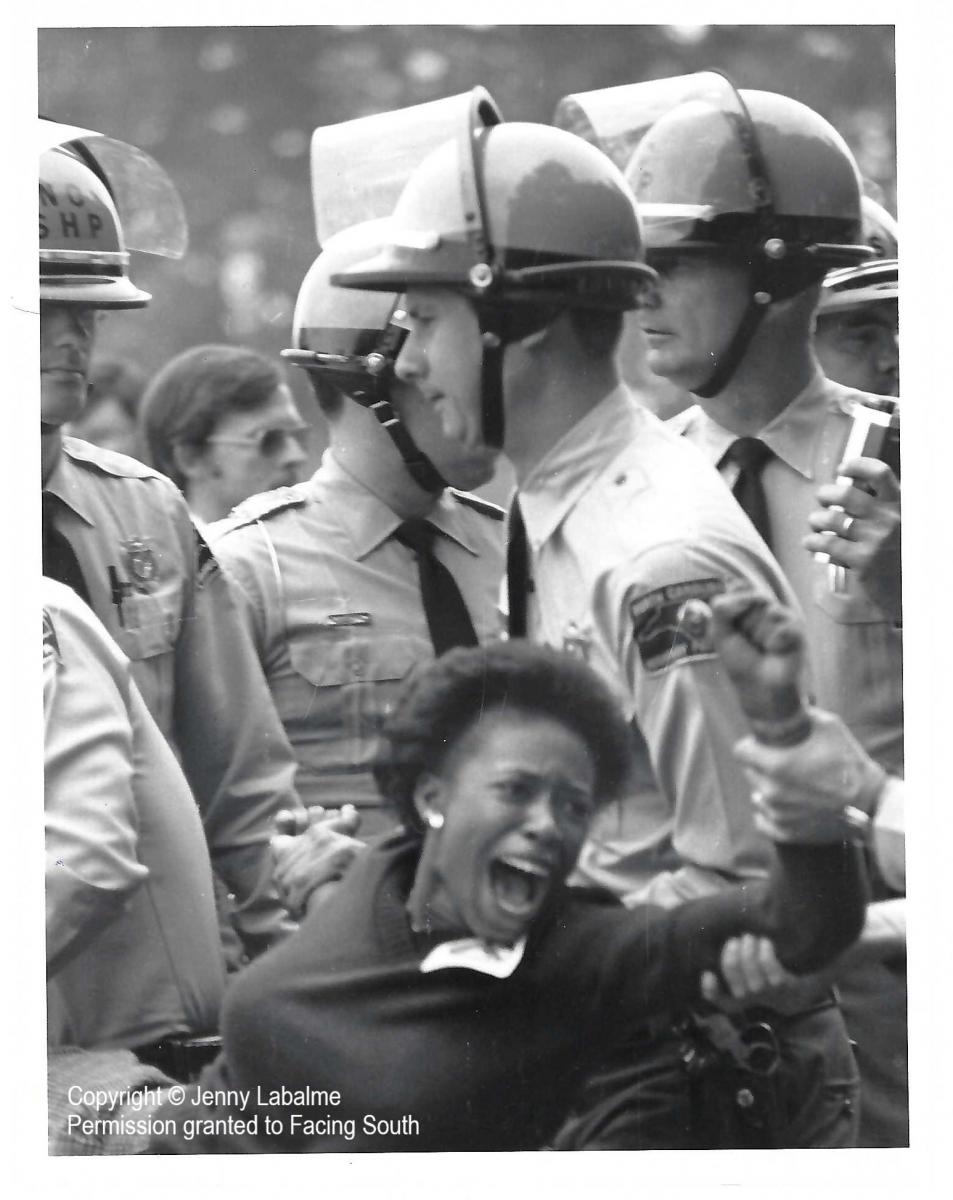

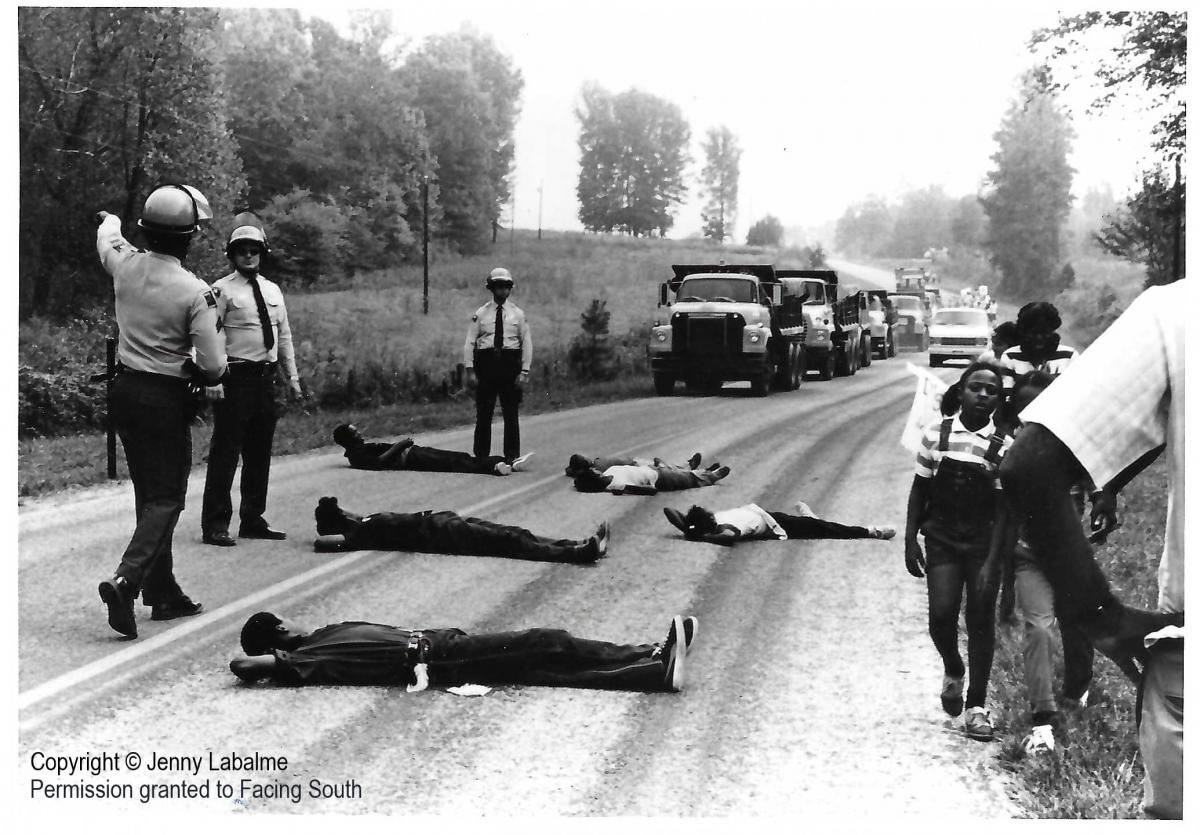

"I think in these visuals, you see the contrast between officers in their riot gear with their billy clubs and their guns and smartly pressed suits. And you have a bunch of ragtag protestors, many of whom are women and children. And then you have these enormous trucks carrying toxic-laden soil," she said. "I hope that when people look back and see what this small community did that was pretty powerless, politically, at the time — I mean, it took 40 years for the EPA to announce $3 billion for environmental justice — I just hope it gives people hope in this country and elsewhere in the world that their struggles are not in vain."

We are republishing Labalme's essay, along with her photographs, in its entirety. The piece is adapted from and builds on a booklet she published shortly after graduating from Duke titled "A Road to Walk." Labalme went on to work as a photojournalist and journalist for publications including The North Carolina Independent (now Indy Week, in North Carolina), the Mexico Journal (in Mexico City), the Anniston Star in Alabama, and the Indianapolis Star.

For more about the legacy of the Warren County struggle, read a lecture delivered by Ben Chavis, another key figure in the environmental justice movement, at Duke University earlier this month in commemoration of the uprising's anniversary. — Olivia Paschal

During the fall of 1982, headlines about a protest over the burial of dirt laced with PCB (polychlorinated biphenyl) crowded the front pages of North Carolina newspapers. Warren County, a rural, majority black county in northeastern North Carolina had been chosen as a dumping ground for toxic chemicals. Three lawsuits and a series of public hearings had failed to halt the state's plans to bury the PCB waste in their county. As a last resort, residents mounted a grassroots campaign of civil disobedience against the dump.

Ken Ferruccio, who lives four miles from the landfill, was angry. "If this isn't the major civil rights issue in the nation," he declared, "there's never going to be one." On September 15, 1982, a multiracial group of 130 people marched two miles from their rallying point at the Coley Springs Baptist Church to the site where the waste was being brought in by truck. Carrying anti-PCB signs, protestors chanted, "The people united will never be defeated." FBI agents and 100 North Carolina highway patrolmen stood watch. A national guard helicopter hovered over the march route.

Leading the march were Ken Ferruccio, a local community college teacher; Rev. Luther G. Brown, pastor of the Coley Springs Baptist Church; and Rev. Leon White, field director of the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice in Raleigh. A plethora of journalists and photographers recorded the arrests of 55 people who tried to block the yellow Department of Transportation dump trucks by laying down in the road. The protest attracted national attention that first day, receiving coverage on the CBS evening news. After six weeks of marches and arrests, Time cited the demonstration as "the most significant protest against a local government's selection of a toxic waste dump in recent memory."

Midnight Bandits

Although the civil disobedience began in 1982, the controversy really started four years earlier. During the summer of 1978, the Raleigh-based Ward Transformer Company deliberately drippled 31,000 gallons of PCB fluid along 240 miles of North Carolina roadways in 14 counties. It was a classic case of illegal midnight dumping and one of the largest PCB spills in American history. In some areas, concentrations of PCB were as high as 10,000 parts/million, 200 times above the contamination level set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). PCB - a chemical commonly used in electrical transformers - has been found to be carcinogenic in laboratory studies. In 1976, the Toxic Substances Control Act banned the manufacture of PCB.

Soon after discovering the spill, the state of North Carolina and the federal government sued the waste disposal company- eventually winning damages - but the state was still responsible for cleaning up the mess. Governor Jim Hunt and state officials considered several disposal options:

- Bury the waste somewhere in North Carolina at a cost of $2.5 million.

- Truck the tainted soil to an existing disposal site in Alabama. The state initially estimated that this plan would cost $12 million but later adjusted the figure to $6.85 million.

- Transport the PCB to an EPA-approved incinerator in New Jersey, Arkansas, or Texas. Logistics and costs made this plan prohibitive. No cost was estimated.

- Extract the PCB from the soil and detoxify the chemical. This is not an EPA-approved method.

- Treat the PCB along the roadside. Although this is not an EPA-approved method, the state petitioned to have the restriction temporarily suspended. The EPA denied this request on June 4, 1979.

State officials concluded that the best option involved scooping up an estimated 40,000 cubic yards of the contaminated soil and burying it in North Carolina. The federal government provided $2.5 million from EPA's "superfund" and the state figured its costs at $450,000. After examining 90 potential landfill sites for the waste, state officials discovered most could not meet all of EPA's requirements, especially two: that the bottom of the landfill be at least 50 feet above the groundwater; and that the site be located where there are "thick, relatively impermeable formations such as large-area clay pans."

The shallow water table in Warren County would allow only a seven-foot margin from the bottom of the landfill, and sample borings showed only small amounts of clay present within the highly permeable soil. Nevertheless, on June 4, 1979, EPA waived both these regulations and gave North Carolina final approval to construct a PCB landfill in Warren County.

State officials first announced their decision to bury the PCB-laced soil in the Shocco Township of Warren County in December 1978. No county resident had received prior notification of the plan to build a PCB dump in their community. People read the news in the paper five days before Christmas. The reaction was immediate and uniformly hostile. "It looked like Big Brother was coming down and telling us what to do," said Charles Johnson, the Warren County attorney.

The state scheduled a public hearing for January 4, 1979, but the two-week interim period gave Warren County citizens little time to organize. Ken Ferruccio criticized the timing of the state's announcement: "How could anyone form an intelligent judgment based on facts which he couldn't possibly get in a two-week period of time on an issue as complex as toxic waste disposal? And how could anyone organize opposition, even if he had a solid basis for it, during the holidays?"

Despite the short notice, within two days of the state's announcement residents organized a telephone network. Ken Ferruccio informed residents about a community meeting on December 26th, and Deborah Ferruccio began contacting educational and religious leaders in the area. Several other people began work on a PCB fact sheet to be distributed at the citizens meeting.

On December 26, 100 people formed a group called the Warren County Citizens Concerned About PCB, an organization often referred to as the Committee. A secretary and several individuals were appointed to represent the Committee, which later evolved into a more formerly structured organization.

On January 2, 1979, more than 25 people spoke at the county commissioners' meeting, appealing for their help. A representative from the local branch of the NAACP and Joseph Lennon, director of the Warren County Health Department, both shared their misgivings about the landfill and waivers the state had requested. After the two-hour meeting, the commissioners reached a unanimous 5-0 decision against the dump. Copies of their resolution opposing the PCB site were sent to Governor Hunt, the EPA, and state officials.

The Politics of Isolation

At the public hearing on January 4, over 700 residents packed the National Guard Armory and listened to people speak for nearly eight hours, until 2:30 a.m. Ninety-two people had signed up to air their concerns. Many speakers argued that the state's decision was made as much on racial and political grounds as on weak scientific evidence. Warren County's population was then 64 percent black, the highest percentage of any county in the state. Shocco Township, the site of the landfill, was 75 percent black. An unincorporated township, Shocco had neither a mayor nor a city council, and the county itself was ranked 97th in per capita income (out of 100 North Carolina counties).

These statistics reinforced residents' claims that a poor, rural area with negligible voting and economic power was consciously selected for the landfill. (A 1983 report by the U.S. General Accounting Office later confirmed that the majority of landfills in the southeastern United States are located in areas where the population is predominantly black and the mean income is below poverty level.)

State officials dismissed charges that the location of the landfill was chosen for political and racial reasons. Defending their decision, officials said the site met environmental standards, was located in a sparsely populated community, and was available for purchase. But Charles M. Mulchi, a soil scientist hired by the Warren County community, raised scientific objections about the safety of the site at the public hearing. After conducting a preliminary analysis, Mulchi said the kaolinite clay at the site could not meet the compaction criteria for a PCB landfill and the site could not be made safe through landfill engineering and design.

Heated exchanges between Warren County citizens and state officials continued for the next four years. A multiracial group of residents submitted a series of questions to Governor Hunt. The county commissioners complained that no environmental impact statement had been prepared, a procedure required by the North Carolina Environmental Policy Act State officials admitted the county commissioners were right, but 20 months passed before they released an environmental impact statement on the removal and disposal of the tainted soil. Ken Ferruccio who spearheaded much of the work on the Committee barraged Governor Hunt with letters. Numerous complaints about the dump also appeared in letters to the editor of the local paper, the Warren Record.

With the state environmental agencies solidly behind Governor Hunt and the larger issue of toxic wastes only beginning to gain public notice in the state, the committed core of Warren County activists were hard pressed to find allies for their struggle. The Committee began to fear that the landfill would become a chemical dumpsite for other hazardous wastes. State officials never publicly explained why they purchased 142 acres of land when only 20 acres were needed for the PCB landfill; and there were indications that the Hunt administration wanted to establish an area for burying toxic substances since no such facility existed in the state. On March 28, 1979, J.K. Sherron, the director of the state property office, wrote Hunt's secretary about the "overriding concern ... for a chemical dump site in North Carolina" and concluded, "Even if this [Warren County] site is not ultimately used for PCB disposal, it could be used for other chemical wastes."

In a relatively unsuccessful effort to generate more political waves, the Committee targeted the 1980 gubernatorial race, hoping to make the PCB controversy and hazardous waste disposal a campaign issue. They asked the candidates for their opinions on these environmental problems. Hunt, confident of his re-election, wrote back a short note thanking the committee for the memo, which he had read "with interest" and passed on to members of his administration for consideration and action. His chief Democratic rival, former Governor Bob Scott, responded with a three-page letter which concluded, "It is my belief that Warren County was chosen by the Hunt administration as the site for dumping the PCB problem because Warren has very few votes."

Courtroom Frustrations

Legal challenges also proved frustrating, though they bought time for other organizing activities. Prior to their 1982 direct-action protest, citizens filed three lawsuits. In August 1979, members of the Twitty family sued the state because they lost their chance to raise Perdue chickens on property adjacent to the dumpsite. Perdue officials had told them the chickens would be too close to the proposed PCB landfill. In 1980, after a superior court judge upheld a preliminary injunction against the sale of the 142 acres to the state, the county commissioners decided to file a suit to permanently block the disposal of PCB in Warren County.

On November 25, 1981, U.S. Eastern District Judge W. Earl Britt ruled against both lawsuits. Britt said he sympathized with the citizens and admitted that the state "cannot guarantee the success of the planned system." But he concluded that government officials had fulfilled their legal obligations by taking many precautions to insure the storage site would not pose an environmental threat to the community. Both plaintiffs appealed their suits to the 4th District Court of Appeals, but state officials confidently proceeded with the bidding process for the landfill's construction.

On May 26, 1982, the day after the state and EPA officials signed an agreement for financing the cleanup, the Warren County Board of Commissioners withdrew its lawsuit in exchange for an agreement that the state-owned 142 acre area would be surrounded by 123 acres of land to be owned by the county. Walter "Jack" Harris, commission chairman, said the board took the dramatic reversal for several reasons: Their attorneys suggested the commissioners could lose their court appeal and end up gaining nothing; a county-owned buffer around the site would enable them to control the dumpsite's expansion and thereby keep the area from becoming a regional waste facility; and the state agreed to add new safeguards in the landfill's construction.

Residents were furious with the county commissioners and felt betrayed. Two weeks later, 90 angry citizens gathered at the courthouse. But George Shearin, the only black county commissioner, was the only member who appeared to explain the board's decision to drop the law suit. Unconvinced, the citizens at the meeting unanimously decided to sue the state.

In July 1982, residents filed their final lawsuit in district court for an injunction to halt landfill construction. The suit listed several complaints: The planned PCB dump violated the civil rights of Warren County residents; the state violated its own laws by overriding local ordinances against the dump; the state's environmental impact statement failed to make an accurate assessment of the long-term impact of the landfill because it was based on the false premise that the dump would not leak; and the site was chosen because of the area's high proportion of black residents and relatively poor political representation.

On August 10, 1982, Judge Britt denied citizens' request for an injunction. The judge said that other people's interests were at stake, namely those who lived along the contaminated roadsides. Britt added that "there is not one shred of evidence that race has at any time been a motivating factor for any decision taken by any official - state, federal, or local - in this long saga."

Taking It to the Streets

After exhausting all legal remedies, Warren County residents decided they would have to turn to civil disobedience in a final effort to block the opening of the landfill; their lawyers had advised them that their protests could draw national attention. No one in the Community had experience in demonstrating. Committee members were also unsure if they should get arrested or if they needed a professional bondsperson. There were many questions and unknowns, not the least of which was who would coordinate and lead the movement.

The Committee authorized Rev. Luther Brown, pastor of the Coley Springs Baptist Church, to find whomever he felt was qualified to come into Warren County to give guidance to their protest Rev. Brown chose Rev. Leon White. White was not a newcomer to Warren County. Although he lived 45 miles away in Raleigh, he had been pastor of the Oak Level Baptist Church on the edge of county for 21 years. He served as the field director of the Commission for Racial Justice, a national civil rights advocacy branch of the United Church of Christ. And he had been active in organizing students in Warren County in 1970 when there were problems with school integration.

Coley Springs Baptist Church soon became the headquarters for all pre-march organizational details. Located only two miles from the dumpsite, the church was logistically the perfect spot to hold nonviolent workshops and rallies. White thought it would be a good idea to hold a "practice march" before the state began trucking in the contaminated soil. The practice demonstration would familiarize people with what marching entailed; it would deliver an ultimatum telling the governor that if he did not reconsider, protestors would establish a blockade; and it would get the press interested in the controversy. Four hundred people showed up for the practice march on September 13.

Hunt refused to comment on the PCB disposal during the few days before the landfill opened. But on the first day of the protest, when 55 people were arrested for blocking trucks, Hunt said storing the PCB waste in the Warren County landfill would protect the health of North Carolinians in the "finest manner possible.” EPA officials said the Warren County landfill was built with the most recent technology and therefore was superior to other troubled dumpsites around the nation. State officials added that the landfill in Warren County was overdesigned and hailed it as the "cadillac of landfills."

"We're not out to appease people," said Governor Hunt "We are out to get the job done and to protect our folks. In time I think they [the Warren County people] will come to believe it is relatively safe. It will take awhile."

The persistent grassroots opposition surprised state officials. Demonstrators protested every day during the six weeks the state transported 7,223 truckloads of waste to the 20-acre landfill. On some days, as many as 500 people would show up and march from Coley Springs Baptist Church to the landfill site. "They didn't expect us to organize," said Henry Rooker, a white Warren County resident. "But we're gonna fight. It's one thing to be poor, it's another to be poor and poisoned."

Strategy and image were both important for the success of the protest. As the marches continued through September and into October, they attracted a number of national environmental and civil rights leaders who forcefully linked racial and conservation issues. Lois Gibbs, a leader in the Love Canal fight in New York, and EPA official William Sanjour spoke to protestors and pledged their support. Sanjour, the chief of EPA's Hazardous Waste Implementation Branch, voiced his own skepticism about landfills: "I have watched for many years to see the EPA and landfill operators try one technology after another to make landfills work and none of them ever has."

Congressman Walter Fauntroy and SCLC president Joseph Lowery echoed residents' claims that the landfill siting was racially motivated, and they helped keep the protest in the national media by being arrested themselves. The influx of prominent civil rights leaders was crucial for the morale of local residents; but competing personalities and agendas also created new tensions over who was in charge and allowed the state to claim "outsiders" were engineering the movement in Warren County.

An ill-fated attempt to build a statewide coalition of groups fighting toxic waste facilities offered little help for Warren County. Some members of North Carolina Citizen Action on Toxic & Chemical Hazards (N.C. CATCH) were unable or unwilling to travel to Warren County to participate in civil disobedience, the tactic that came to dominate the anti-PCB campaign. CATCH members helped get the commissioners in one Piedmont county to pass a resolution that called for detoxifying their PCB-contaminated roadways in place rather than risking greater harm by digging up the soil and taking it to Warren County. But, in general, despite the statewide press coverage of the arrests, little concrete political or strategic support came from other areas, leaving the Warren County residents still largely isolated. The burst of media attention and intense involvement of civil rights veterans came too late to build enough momentum to reverse the state's determined effort to bury the PCB problem in Warren County.

There were 523 arrests during the protest, with no incidents of violence or injury. Although Hunt's image as a progressive governor was tarnished by the press coverage, he showed little interest in meeting with the protestors until October 8th. The meeting scheduled that day caused a flurry of intense debate among the protest leaders over who would attend and what they'd say. Unrealistic expectations of what the meeting with Hunt would yield, as well as conflicting goals among the delegation members, helped undercut the protestors' waning solidarity.

When the delegation returned to Coley Springs Baptist Church after talking with Hunt, citizens hoped to hear answers. But Hunt had offered no new options and had only defended his decision to the Warren County delegation. An angry group of people started shouting at the delegates in the church demanding results. Jim Ward, who first told the crowd about the meeting said, "I got crucified ... . People said, 'What I hear you saying is that you agree with the governor."' One delegate member described the scene at the church as a "mass confusion."

Meetings and protests continued after the exchange in the church, but more problems surfaced. So many people were speaking at meetings and issuing different ultimatums that demonstrators were unable to rally around a specific goal. Some people wanted to stop the trucks, others argued the soil in the landfill should be detoxified, and others wanted the dirt dug up and hauled elsewhere. The lack of a clear focus damaged the spirit of the protestors, highlighted personality conflicts, and weakened the fragile yet potent unity across race and class lines.

Negative editorials about the protest in the Warren Record fueled ambivalent feelings among the non-demonstrating citizens. Bignall Jones, the 82 year-old editor of the paper felt that the fight against the state should have ended in the courts. Jones believed that the landfill was safe and that PCBs were not as dangerous as some residents claimed.

Bubbling Sludge

While the state continued to assure residents that the landfill would not leak, state officials faced three serious problems three months after the dump was covered and "capped" in late November 1982:

- About 500,000 gallons of water had accumulated in the landfill from extremely heavy rains prior to the capping. To alleviate this problem, engineers solidified some of the water with cement dust and pumped the rest of the water out through an activated carbon filtering system.

- Serious erosion problems developed at the site, including wash-outs of cap material and soil areas surrounding the landfill. One state engineer acknowledged that one gulley was over his head when he stepped into it To repair the damage, the state regraded the area with bulldozers, built silt fences and slope drains, and heavily mulched the site.

- A build-up of non-toxic methane gas within the landfill caused the liner to balloon in a number of places. To correct this problem, state officials followed EPA orders and poked holes in the liner with pipes for the gases to escape through.

Two experts from the Washington-based Hazardous Waste Organizing Alliance examined the site and said they had never seen a landfill deteriorate so quickly. A spokesperson for the organization questioned the future security of the dump if it took only three months after capping for such drastic deterioration to occur.

Victory or Defeat

Sentiment in Warren County about the protest varies from disillusionment, to annoyance, to pride. Some people think their protest accomplished nothing because they were unable to stop the PCB dump. Other residents consider the protest a nuisance and waste of the estimated $787,000 dollars it cost the state to police the demonstrations. But others credit the protest with several accomplishments:

- Many blacks and whites united together for the first time on a controversial issue, and they built on their new relationships for political and other gains.

- Voters in November 1982 elected a black state representative and their first black sheriff, and they tipped the scales on the county commissioner board by giving blacks a three-to-two majority.

- Residents stopped the state from making Warren County a home for additional hazardous wastes. They won a commitment from Governor Hunt that no other wastes would be stored at the site.

- Governor Hunt also imposed a statewide two-year moratorium on permits for new hazardous waste landfills, while safety standards and siting criteria were clarified.

- Local activists also felt they brought national attention to the hazards involved in disposing of toxic wastes and exposed the fact that most landfills are located in predominantly poor and black communities, an issue which civil rights organizations around the country began addressing.

Four and a half years after the protest, the N.C. Division of Health Services continues to monitor the landfill on a monthly basis. According to their reports, no harmful levels of PCB have leached through the landfill or into the four groundwater monitoring wells at the site. Although no PCB leakage has been detected, residents still have many doubts about the landfill's safety. At churches, PTA meetings, and public gatherings, people still talk about the landfill and worry about its long-term health hazards.

Dollie Burwell, who lives less than four miles from the dump, has a filter on her kitchen faucet. "I don't trust any of the state's reports," she said. But she and her neighbors cannot afford to have their wells monitored independently. Burwell 's house has been on the market for three years, but no one wants to buy it when they hear how close it is to the landfill. "I feel a sense of relief, from a moral point of view, when people don't want to buy it," said Burwell. But she does not want to live near the dump either.

Tags

Jenny Labalme

Jenny Labalme photographed the 1982 Warren County protests as part of a documentary photography class she took while an undergraduate at Duke. She spent almost two decades working first as photojournalist for The North Carolina Independent (now Indy Week), and later as a journalist for the Mexico Journal, The Anniston Star, and The Indianapolis Star, and is currently the executive director of the Indianapolis Press Club Foundation.