Rural and low-income voters build power to transform the South

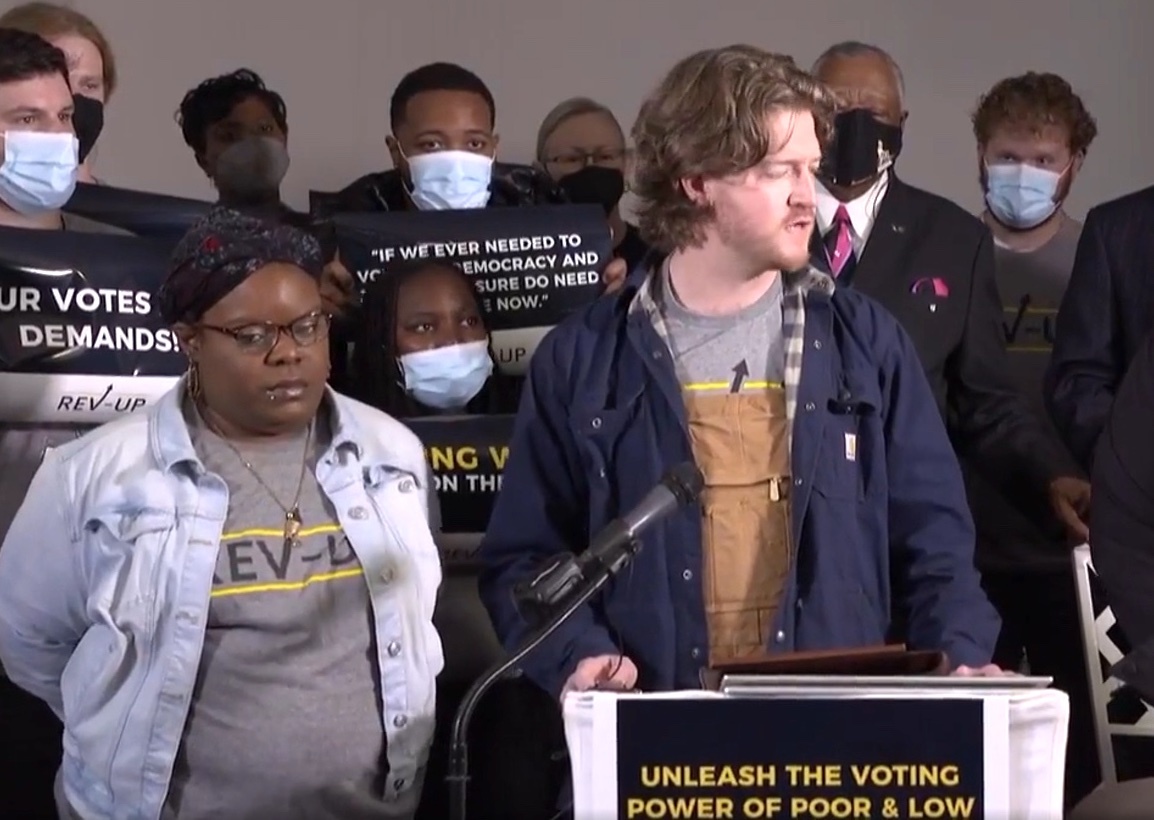

REV-UP organizers Cierra Brown of Durham (left) and Jacob Brooks of Ennis, North Carolina (at podium), spoke at a recent press conference announcing a new effort to engage low-income communities across the state and fight for anti-poverty policies. (Image is a still from this video).

Rural and low-income voters played an influential role in this year's midterm elections, giving Democrats the needed boost to maintain the U.S. Senate and defy predictions of a Republican "red wave." Observers note that this level of engagement counters common misperceptions that rural and low-income people are apathetic about politics or inconsequential to electoral outcomes.

Their participation was due in part to the work of civic engagement organizations on the ground — groups that were formed to directly target poor and rural communities.

Motivated by the impact of congressional anti-poverty measures passed during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, low-income voters emerged as a powerful voting bloc that can shape the outcome of future elections. In 2021, when these safety-net policies were in effect, the number of Americans who were poor or low-income dropped by 20%, and child poverty was nearly cut in half.

Although it is commonly believed that low-income voters are not interested in politics or elections, their turnout in recent years shows otherwise. According to a recent study by the Poor People's Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival titled "Waking the Sleeping Giant: Low-Income Voters and the 2020 Elections," these voters accounted for nearly one-third of the total voting population in both 2016 and 2020.

"We seldom hear about poverty in elections," wrote Poor People's Campaign Policy Director Shailly Gupta Barnes. "But poor people vote. In 2020, one-third of all votes were cast by poor or low-income people — a figure that rose even higher in some battleground states in the South and Midwest. In all, 50 million low-income people voted in that election."

Organizers have stressed the political power that this voting bloc could wield if it were fully engaged. For example, approximately 3.4 million poor and low-income North Carolinians were eligible to vote in 2020. However, one out of every three of those voters failed to show up to the polls that year.

Among the main reasons many eligible low-income voters don't participate in elections is because they feel as though they are ignored, and their priority issues are not being addressed. But work is underway to change that.

Ahead of this year's midterm election, the Poor People's Campaign exceeded its goal of reaching out to 5 million low-income voters nationwide. Using the theme of "If We Ever Needed to Vote for Democracy and Justice, We Sure Need to Vote Now," the campaign targeted 15 states as strategic organizing locations: Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin, and West Virginia. For instance, the campaign contacted over 718,000 North Carolinians and over 731,000 Georgians ahead of election day.

"Numbers like these can make all the difference," noted Gupta Barnes.

Now organizers with the Georgia chapter of the Poor People's Campaign have launched a statewide canvassing, text-banking, and social media campaign to reach out to low-income voters ahead of the Dec. 6 U.S. Senate runoff election between incumbent Democrat Raphael Warnock and Republican challenger Herschel Walker after neither won more than 50% of the vote on Nov. 8.

Don't write off rural voters

The results from this year's election show that Democrats performed better because of votes coming from rural communities. Advocates note that the misconception that rural communities don't participate in elections is based on stereotypes that perpetuate discriminatory patterns and deny the existence of the increasingly diverse populations that live in these areas.

Recent 2020 census data found rural areas are becoming more diverse even as their overall population declines. For example, experts note that Latinos are one of the quickest growing populations in rural, nonmetropolitan areas, and communities of color make up nearly a quarter of all residents in these areas of the country.

"When we write these communities off, we're not only writing off the rural white vote, but we're also writing off rural voters of color," George Goehl, a community organizer focusing on rural areas, told NPR. "And I think writing off either is a big mistake."

Even in rural places in North Carolina and Georgia, which in the past have been painted as Republican strongholds, Democrats were competitive, running up margins and flipping some districts. While most rural counties in North Carolina still tend to favor Republican candidates, their residents make up 15% of the state's Democratic vote share.

For example, Democrat Wiley Nickel won North Carolina's competitive congressional seat. Observers noted that voters from rural Johnston County, along with rural parts of Wake, Harnett, and Wayne counties, pushed Nickel to victory.

Rural North Carolina voters also blocked Republicans from winning a veto-proof supermajority in the state legislature. In the state House District 73 race in rural Cabarrus County, Democrat Diamond Staton-Williams defeated Republican Brian Echevarria by 629 votes out of 27,587 cast. Organizers with Down Home North Carolina, a group that advocates for residents of the state's small towns and rural communities, knocked on 35,000 doors and had nearly 8,000 conversations in the district.

"Because rural N.C. counties often 'go red' election after election, progressives often discount us as a lost cause," Dreama Caldwell, co-director of Down Home North Carolina, wrote in a recent op-ed. "This election, however, we flipped the script. Small town and rural voters saved the day."

REV-UP for power

While rural communities cannot be completely defined by poverty, it's more concentrated there compared to other parts of the country. Organizers emphasize the importance of engaging with these communities in a way that understands this reality.

For example, nearly 73% of counties with the lowest median income and 76% of those with the highest percentage of people living in poverty are located in the U.S. Southeast and Southwest. About 80 of North Carolina's 100 counties are classified as rural, and another 12 as semi-rural. In Wayne County, a rural county in Eastern North Carolina, approximately 42% of residents live under 200% of the poverty line.

A coalition of advocacy organizations is stressing the importance of long-term, concentrated, and sustained engagement in such communities.

On the first day of the early voting period in October, low-income voters from across North Carolina gathered with voting rights advocates, religious leaders, and other organizers at a press conference hosted by Repairers of the Breach, a religious-associated anti-poverty advocacy group, to announce a new program to engage low-wealth voters in the state, with efforts heavily concentrated in rural communities. The press conference also included representatives from the Poor People's Campaign, Unlock Our Vote, Advance Carolina, and Forward Justice. Speakers challenged advocacy groups and elected officials who visit their communities only during election season.

"We don't see politicians, but every two years, every four years, they show up, and they talk a lot and what they say is good," said Jacob Brooks of Ennis, North Carolina. "But nothing seems to happen."

Organizers say the Repairers Educational Voter Uplift Project ("REV-UP") will use an organizing and advocacy approach "rooted in a long-term relational model focused on elevating local leaders from within under-resourced communities where voters are increasingly overlooked and ignored." This new initiative will engage people not only during the electoral season but year-round to amplify the collective power of poor communities at the local, state, and federal levels.

"REV-UP is laser-focused on building power and elevating the quality of life among poor, low-wealth, and low-wage communities," said Executive Director Andrew Simpson. "Forged in the mold of moral fusion, this movement is bringing together diverse groups of North Carolinians who are united in their demands that elected leaders take bold action to fight poverty and restore our democracy."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.