South Carolina gerrymandering case could further erode the Voting Rights Act

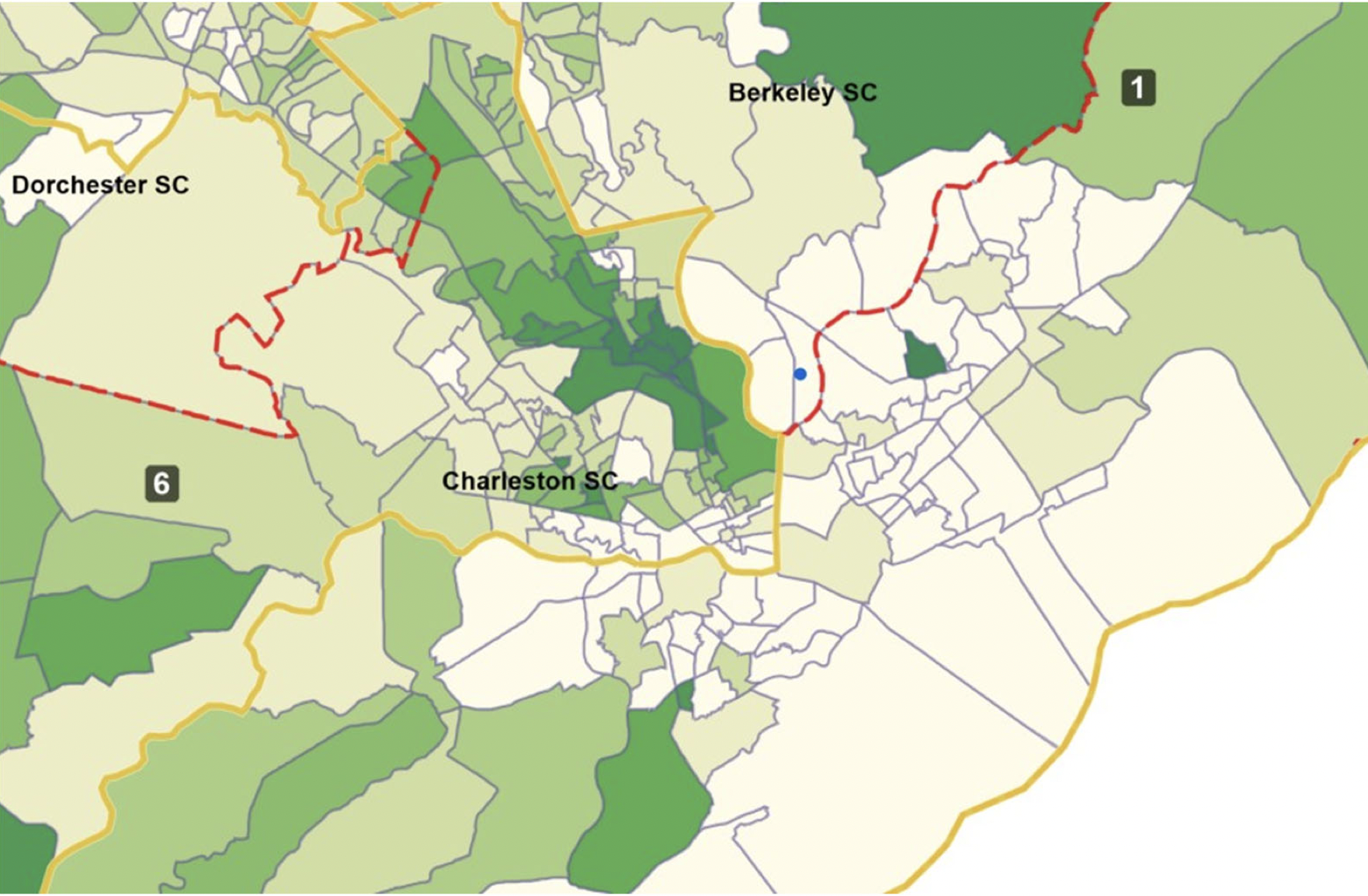

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear a racial gerrymandering case out of South Carolina in which advocates maintain that the state legislature discriminated by moving Black voters in Charleston County from the 1st to the 6th Congressional District. Advocates worry that the case could further impair Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and possibly open the door to more racial gerrymanders undermining Black communities' political influence across the South. (Map from court filing.)

In January, a three-judge federal district court panel unanimously ruled in a case originally brought by the state NAACP and an individual voter that South Carolina's 1st Congressional District was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander and had to be redrawn. The legislature has appealed that ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has agreed to hear the matter in its next term that begins in October.

Legal scholars say allowing this kind of gerrymandering would have damaging implications for voting rights nationwide and especially in the South, a region with a long and vicious history of voter discrimination. The case strikes at critical tools to protect voting rights, including a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).

"The recently adopted congressional map denies Black South Carolinians political representation at the federal level," said Brenda Murphy, president of the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, which is a plaintiff in the case. "The maps represent an attempt to prevent Black communities from electing congressional representatives who would be responsive to their needs."

South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP v. McMaster challenges the congressional redistricting plan enacted by South Carolina's Republican-led state legislature after the 2020 census. The plan preserved the GOP's 6-to-1 seat majority in the state's U.S. House delegation and gave Republicans an additional edge in the coastal 1st District, now represented by Republican Rep. Nancy Mace, a former state lawmaker and Trump campaigner.

The case brought by the state NAACP — with help from the Legal Defense Fund, American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU of South Carolina, and Arnold & Porter law firm — argues that "the Legislature sorted Black voters on the basis of race without a compelling reason and also purposely engineered the map to dilute Black voting power."

The federal judges agreed, finding that Republican lawmakers deliberately moved 62% of Black voters in Charleston County from the 1st to the 6th District, which Black Democrat Jim Clyburn has represented for over 30 years. This practice of concentrating the opposing party's voting power in one district to reduce their power in others is known as "packing." The judges concluded that the district was drawn with racially discriminatory intent in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

The case marked the first time South Carolina's voting maps had been subject to scrutiny by the courts since the U.S. Supreme Court in a 2013 case out of Alabama — Shelby County v. Holder — struck down a provision of the VRA requiring states and other jurisdictions that engaged in voter discrimination in the past to get federal approval for new district maps and other election changes. South Carolina's GOP-controlled legislature appealed the lower court's ruling, arguing that partisan advantage — not race — was the basis for their new map.

Restoring the VRA

Voting rights advocates fear the high court's ruling in the appeal could have a devastating impact on Section 2 of Voting Rights Act, paving the way for more voter discrimination ahead of the 2024 presidential election. Since Shelby, Section 2 has become the main tool for challenging discriminatory voting policies under the VRA. This provision clearly bans voting practices and policies — including redistricting maps — that discriminate on the basis of race.

The Supreme Court has already issued a ruling that weakened Section 2. In its 2021 decision in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee out of Arizona, the court limited the section by deciding that it can be used to strike down voting restrictions only when they impose substantial and disproportionate burdens on voters of color. The court is also currently considering Allen v. Milligan (formerly Merrill v. Milligan), a VRA redistricting case out of Alabama; as part of that case the court suspended the VRA's ban on racial gerrymandering ahead of the 2022 midterms, permitting Republican lawmakers across the South to draw maps that curbed Black voting power.

Meanwhile, the court is also considering Moore v. Harper out of North Carolina. That case hinges on the controversial independent state legislature theory, which holds that only state legislatures should control federal elections. If the majority embraces the theory, the precedent would further limit challenges to discriminatory maps.

With what's left of the VRA in the GOP's crosshairs, the Congressional Black Caucus is preparing for another push to pass federal legislation restoring the gutted law. At the recent National Summit on Democracy & Race, Democratic Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama announced that she plans to reintroduce the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which among other things would restore the VRA's preclearance provision for election changes in jurisdictions with a history of discrimination.

Legal experts say the South Carolina appeal case will critically define the limits of how much a legislature can consider race as it draws new maps. A ruling is expected in the run-up to the 2024 elections, when changes in just a few districts could have a major impact on the political power of Black communities — and ultimately determine who controls the House after the next presidential election.

"Changes in a handful of states between now and 2024 could shift the advantage in favor of one party or the other in the battle for a closely divided House," wrote Michael Li, senior counsel for the Brennan Center's Democracy Program. "Whether those changes make maps fairer or more gerrymandered remains to be seen."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.