Honoring John Lewis' expansive vision of American democracy on the 59th anniversary of Bloody Sunday

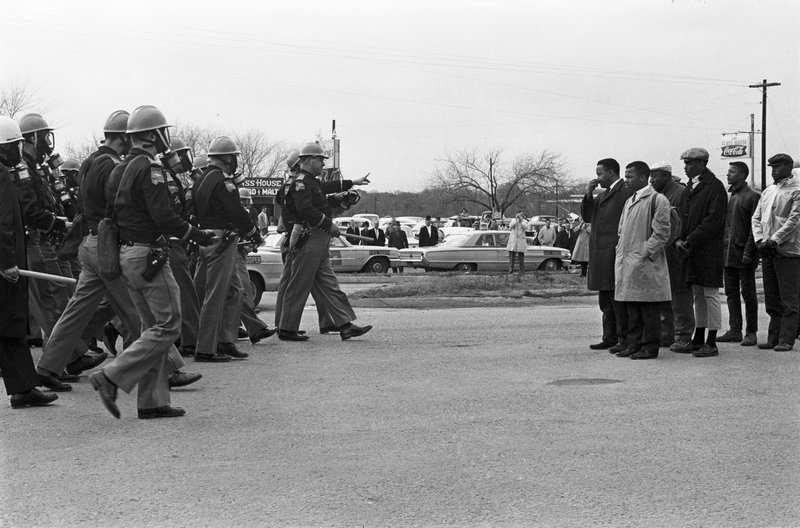

A 25-year-old John Lewis, then chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, leads hundreds of protesters on a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to draw attention to the need for voting rights for African Americans across the South. They were met by Alabama police, who assaulted the marchers with nightsticks and fractured Lewis's skull. (National Archives photo by Spider Martin via the IIIP Photo Archives Flickr account.)

Congressman John Lewis was one of democracy's most committed guardians. I met the Congressman when I was 19 years old during an Atlanta-based fellowship that was named in his honor. I had been following his life for years—recalling stories my elders told me as a child, studying the history of social movements in college, and, during a summer I spent in the Mississippi Delta, meeting Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) members who worked alongside Lewis. So when I finally met the Congressman in the bright natural lighting at Georgia State University, my reverence was accompanied by familiarity and calm. As the 59th anniversary of Bloody Sunday approaches, and in this moment of escalating American crises, I'm reflecting on the lessons he left behind for us.

John Lewis joined the Black Freedom Movement as a teenager, and his activism played a critical role in the passage of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He served as chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization that was a political home of some of the most insightful thinkers on American democracy. These included icons like Bob Moses, Ella Baker, Kwame Ture, and Fannie Lou Hamer, whose 1964 nationally televised testimony on the abuse she endured to register to vote captured the attention of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Her speech forced the Democratic Party to grapple with its own exclusionary practices that kept African Americans from fully participating in the political process.

SNCC members and other movement leaders believed that every person has a role to play in securing democracy. Every person, created equally, should have equal civic standing and the ability to shape public life. It's an expansive vision of democracy. It's a vision of democracy based on the principle that every human contains the divine, part of freedom's light. It's a vision of democracy that says politics should not belong to the wealthy and the powerful, but to the sanitation workers, nurses, seamstresses, and other ordinary people who took costly actions to realize their rights. Ms. Fannie Lou Hamer often sang, “this little light of mine,” a reminder to each person in the ranks that they had work to do, light to shine.

One legal manifestation of this democratic vision, the right to vote, was so important to John Lewis that he dedicated his life to its expansion. On March 7, 1965, a 25-year-old Lewis led hundreds of protesters on a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to draw attention to the need for voting rights for Black Americans across the South. They were met by Alabama police, who assaulted the marchers with nightsticks and fractured Lewis's skull. Broadcast on national television, the images of state troopers attacking peaceful demonstrators shifted public opinion and galvanized Congress to pass federal voting rights legislation. Approved by Congress on Aug. 6, 1965, the VRA was one of the landmark achievements of the civil rights movement. It built on the 15th Amendment that granted African Americans the right to vote by establishing a preclearance system requiring states with histories of voter discrimination to get federal approval before implementing new voting laws. But towards the end of his life, Lewis witnessed the undoing of key protections. After the US Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, a flood of voter suppression laws swept the country. In recent years, threats such as intimidation of election workers and voters, misinformation and disinformation on media platforms, and election interference continue to erode a meaningful right to vote.

The United States lost a moral center when Congressman Lewis died in 2021. On this anniversary of Bloody Sunday, one cannot help but ask: what would it take to honor his sacrifice? Honoring our ancestors and fallen angels requires more than sharing their popular quotes on Instagram. A true honoring would be to take seriously the demands democracy's guardians made of us during their lifetimes. The movement that Lewis shaped and was shaped by knew that safeguarding democracy required far more than voting. Civil rights workers recognized the importance of voters knowing about political and legal systems. They established dozens of freedom schools across the South that taught Black history and civics education. The pedagogy was practical and included everything from the importance of county commissioner and sheriffs elections, to the analysis of W.E.B. Du Bois and Harriet Tubman. They reminded Black Americans in the South that they were heirs to a powerful inheritance, despite American political and economic systems that insisted otherwise.

Today we face new barriers to creating and protecting multiracial democracy in the United States. Much responsibility lies with the President, Congress, and the Department of Justice. There are a range of policies that would move the country in the right direction, including the pending John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and Freedom to Vote Act. Many people have lost faith in these national institutions to deliver real material change. Even so, Congressman Lewis and his allies recognized we have work to do in the meantime.

I find hope in the social movements of recent years that have led millions of people to join civic organizations, mutual aid formations, and unions; plan brilliantly choreographed direct actions and rallies; write and create art to influence public opinion; run for local office in the face of slim odds; and hold officials accountable on election day and beyond. These actions don't feel glamorous but, taken a thousand times over, they're the foundation of a healthy democracy. They instill a sense of solidarity with others and remind us of our shared stake in the future we're creating – a freer one, if we make it so.

Tags

Trey Walk

Trey Walk is an organizer, strategist, and writer committed to love, Black liberation, and the freedom of all who live at the margins of society. He has worked with organizations across the country on community organizing, providing direct client services, and winning policy change. Trey is currently based in Brooklyn and he continues to call the Carolinas home.