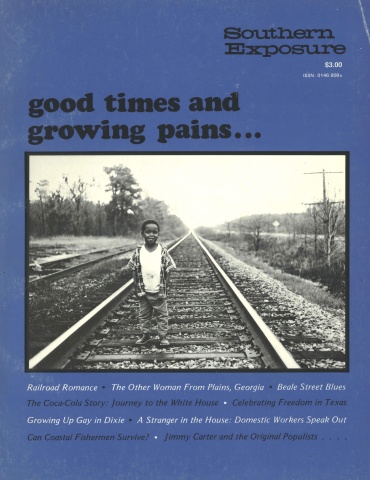

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 1 "Good Times and Growing Pains." Find more from that issue here.

Goin’ to the River,

Maybe bye and bye,

Goin’ to the River,

And there’s a reason why —

Because the River’s wet

And Beale Street’s done gone dry.

W.C. Handy, Beale Street Blues (1916)

It is like a backlot of an old movie studio. Two blocks of old brick buildings, their facades looming over an empty street, their back sides open and showing dingy wallpaper and tin ceilings. Around the abandoned street are acres of parking lots and weed-covered land. Beale Street. The most famous street in Memphis, the one place visitors always ask to see, has fallen victim to a city’s fantasies about what it ought to be.

What happened to Beale Street is the betrayal of the showplace and pride of the black community by the white community that runs Memphis. It’s as if there was a movie here, with a cast of thousands. W.C. Handy, one of its stars, remembers the scene in Pee Wee’s Saloon, where he wrote the first published blues music, Memphis Blues:

Just inside Pee Wee’s entrance door there was a cigar stand. A side room was given to billiards and pool, another to crap games and cards. In a back room there was space where violins, horns and other musical instruments were checked by free-lance musicians who got their calls there over phone number 2893. Sometimes you couldn’t step for the bull fiddles. I’ve seen a dozen or more of them in there at one time. Upstairs a policy game was operated.

Through Pee Wee’s swinging doors passed the heroic darktown figures of an age that is now becoming fabulous. They ranged from cooks to waiters to professional gamblers, jockeys and race track men of the period. Glittering young devils in silk toppers and Prince Alberts drifted in and out with insolent self-assurance. Chocolate dandies with red roses embroidered on cream waistcoats loitered at the bar. Now and again a fancy girl with shadowed eyes and a wedding-ring waist glanced through the doorway or ventured inside to ask if anybody had set eyes on the sweet good man who had temporarily strayed away.1

The world knows Beale Street because of Handy’s music, but the street’s fame pre-dated him and served as the magnet that drew him and thousands of others from the Mississippi Delta, up the Hernando Road that became Highway 51, up the Illinois Central Railroad and out of the drudgery of the rural South. Beale Street produced the first touring circuit for black actors and entertainers in this country, organized in 1907 by F. A. Barrasso and the Pacini Brothers, builders of the Palace Theater on Beale, the most famous black theater in the South.

Until it was vacated, and its roof allowed to cave in, the Palace was the scene of 50 years of vaudeville, concerts, and the famous Amateur Night shows emceed by Nat D. Williams, the first black disc jockey in the South. In the 1920s and 1930s, its Midnight Rambles brought bright and bawdy stage shows to the only theater in town where whites, instead of blacks, sat in the balcony. Beale Street was celebrated again and again by writers like Richard Wright and Langston Hughes and by lesser-known people like Gilmore Millen, who described the place he knew as a police reporter for the Commercial Appeal.

Beale Street is not a legend. Bravely as any lights in Memphis, its electric advertisements dance and twinkle gold and green and blue and red against the facades of its not too modem buildings, and the automobiles and street cars roll down asphalt paving through crowds of Negroes as varied as any in the world.

It is a street of business and love and murder and theft - an aisle where Jew merchants and pawnbrokers, country Negroes from plantations, creole prostitutes and painted fag men, sleepy gamblers and slick young chauffeurs, crooks and bootleggers and dope peddlers and rich property owners and powdered women with diamonds in their chryselephantine mouths, and labor agents and blind musicians and confidence men and hard-working Negroes from sawmills and cotton warehouses and factories and stores meet and stand on comers and slip upstairs to gambling joints and rooming hotels and barber shops and bawdy houses.

It is the main street of the Negro population of a city whose percentage of Negro population is greater than any other city in America, and whose murder rate is the highest.2

These were the scenes of the Beale Street movie. Unfortunately, by the 1950s, the city’s leaders wanted to remake the city in their own image, to falsify it, to create a Beale Street toned-down, cleaned up, and guaranteed safe for the white, middle-class tourist. If Disney could do it for Frontierland, why couldn’t Memphis do it for the home of the blues? By July 11, 1959, the city fathers had reached their decision. Mayor Edmund Orgill announced that Beale Street would be converted into a major tourist attraction for Memphis and America.

Ironically, the Memphis Housing Authority (MHA), an agency created in 1935 to provide public housing, took charge of turning Beale Street into the white man’s fantasy of black culture. By the 1960s, MHA had built thousands of housing units, but it had destroyed far more in its evolving role as the city’s principal agent for acquiring land. Under the “write-down” — the public sacrifice for private gain — MHA bought, cleared and improved huge chunks of land and then turned them over to commercial and industrial developers at a fraction of the real cost. The mandate to provide public housing was clearly overshadowed by the city’s use of the agency to remove rundown neighborhoods.

The Beale Street Urban Renewal Project became the fifth massive MHA project to follow this pattern.3 It encompassed 167 acres, or roughly a 14-block area stretching east from the Mississippi River, including 625 buildings, of which 570 were substandard. Replacement of these decaying buildings had provided the original justification for the project; however, a few years after the acquisition and land clearance had begun, a funding cut by HUD led MHA officials to lop off the eastern half of the project, and with it, the entire provision for construction of new public housing. Several hundred residential buildings (including a number of antebellum mansions) had already been bulldozed, turning the area into one more urban wasteland. MHA blunted the criticism by promising that 615,000 square feet in the western end of the project would be set aside for public housing, but to this day, only one high-rise for the elderly has been built in the area.

With plans for public housing virtually scrapped, all that remained of the Beale Street Urban Renewal Project was a scheme to redevelop the western end of Beale into an entertainment and commercial complex called the Blue Light District, surrounded by high-rise luxury apartments with a million-dollar view of the Mississippi River. But even in pursuing what Martin Anderson (author of The Federal Bulldozer) described as a “regressive program” — displacing low-income people for high-rent buildings — the Memphis Housing Authority proved all thumbs. What began as an intrusion into the heart of black Memphis quickly became a planning and urban renewal fiasco.

Paper Glitter

The first of many versions of the redevelopment dream for Beale Street appeared in the Press-Scimitar on June 26, 1963. Plans called for a “tourist mecca centering around the Memphis Light, Gas & Water Building.” Three years later, MHA announced plans for transforming “drab Beale Street into a glittering jewel complete with a revolving tower-restaurant at the Mississippi River, a riverfront freeway, high-rise apartments, a plaza along Beale and a huge covered commercial mall north of Beale.”4

The hotel and entertainment industries, led by Playboy Club and Holiday Inn, responded with enthusiasm. Even the National Park Service bestowed its official blessing on the proposed entertainment complex, designating two blocks of Beale Street as a national historic landmark. This preservation mandate complicated things considerably, however, because of one of MHA’s criteria for demolishing a building asked, “Will the continued presence of the building deter redevelopment of the area? For instance, will a house of obsolete design discourage private enterprise from erecting expensive high-rise apartments on otherwise valuable adjacent land?” Having destroyed more buildings of “obsolete design” than anyone else, MHA suddenly found its hands tied — landmark structures simply couldn’t be destroyed, not even for “expensive high-rise apartments.” Nevertheless, MHA officials were confident they could find ways to work within the constraints and still get on with building their dream.

Federal preservationists were not their only obstacle. In June, 1967, when MHA received its first $3 million check from HUD for land acquisition, Beale Street property owners woke up to the fact that MHA’s dreams were their nightmares. Beale Street had enjoyed a good mix of small black-owned businesses (including a photo studio, barber college, barber supply firm and shoe shop) and white-owned businesses (furniture stores, discount stores, dry cleaners, cafes, night clubs, liquor stores, and nine pawnshops). The merchants protested that replacing these businesses with a $6 million utility office building would rip the heart out of Beale Street. At a public hearing, Alvin Lansky, owner of Lansky Brothers, the Beale Street clothiers made famous by the patronage of Elvis Presley, B. B. King, and others, said: “You’re forgetting one thing. If you tear down all these buildings, you will no longer have Beale Street and you will defeat your purpose.” For the first time, the public realized that landmarks like the elegant old vaudeville and movie palace, Loew’s State (1912), and Memphis’ first skyscraper, the Randolph Building (1891), would have to disappear to make room for civic improvements like the plate-glass palace “squatting on its man-made knoll,” as Commercial Appeal writer Jefferson Riker put it. In spite of the vehemence of their arguments, Lansky’s and a dozen others’ protests were simply ignored.

The dissenters would not give up easily, however. By the time MHA got ready for its second-year proposal to HUD in 1968, the Beale Street Project cost had jumped from the original $20 million in 1959 to $26 million. The revised dream, drawn up by Memphis architects Walter Ewald and Mel O’Brien, called for jazzing up the facades of the existing Victorian structures along Beale Street with brick and blue-glass colonnades. Recognizing that the decorations were merely token gestures in the overall redevelopment plan, the local shopkeepers turned out in force for the second public hearing, held in August, 1968. They greeted the testimonials praising the project with a chorus of protest that lasted three hours. L. T. Barringer, head of a large cotton business at Front and Beale, wondered why his structurally sound building had been condemned. David Caywood, attorney for the 85 merchants in the ad hoc Beale Street Merchants Association, said he doubted whether new construction like the MLG & W building would be “the type of replacement that would cause W. C. Handy to write good music.” O’Neil Howell, of Ben Howell & Son, Saddlery, Second and Beale, said, “I think you’re creating a Frankenstein that some day you’ll live to regret.”

Twenty days later, the city council adopted a resolution approving MHA’s redevelopment plan. With one swing of the gavel, citizen opposition to the project was rendered obsolete. Predictably, the resolution’s strongest support came from Councilman Lewis Donelson, who later led a Beale Street redevelopment group, and Councilwoman Gwen Awsumb, head of the Office of Community Development which eventually supervised Beale Street’s redevelopment, and William Goodman, one of the largest downtown property owners and a leader of the original Beale Street redevelopment campaign. One of the few dissenting voices at the Council meeting belonged to Alvin Gordon, attorney for the Barringer Cotton Company, who said it would be “unfair to build luxury apartments in the area when additional low-income housing has been trimmed by federal spending cuts.”5 Soon afterwards, the Barringer building was officially cleared away with dynamite.

In the next two years, HUD money continued to pour into MHA for the private development features of the project, and the Authority began speculating that upwards of $100 million in private capital would be attracted into the area to complete the Blue Light District. Meanwhile, the established businesses on Beale Street received their eviction notices from MHA. Maurice Hulbert, the 73-year-old head of Hulbert Printing Company, an all-black firm located at 358 Beale, said, “We know we gotta go.” The evictees were notified that if they stayed, they would be required to remodel their buildings to conform to MHA’s plan for its renewal area. Few had the money that renovation would require. Evie Koen, owner of Koen’s Cleaners and Shoe Shop, 363 Beale, which her father had started in 1914, found that her notice read for the end of January — a mid-winter eviction for a small business. Some evictees went quietly, some went noisily, but nearly all went, firmly convinced that they couldn’t fight City Hall. With them went the real Beale Street, a street long integrated with prosperous businesses run by Italians, Jews, and Negroes, under names like Gallina, Raffanti, Gemignani, or Epstein, Koen, Karnowsky, or Hulbert, Williams, and Hooks. Only empty buildings with boarded-up windows remained, producing a rapidly decaying business environment for the few surviving merchants who found themselves renting from the city’s new slumlord, the Memphis Housing Authority. Not only did MHA fail to maintain the newly acquired property; it deliberately hastened its demise by hacking off the backs of buildings that stuck out over the new alleys that would service the businesses once the proposed Beale Street pedestrian mall was completed. The vacant buildings were soon open to vandalism, and leaking roofs damaged the plaster and structural members inside, forcing renovation costs even higher.

The Best Laid Plans....

While the Authority was clearing up the land and sponsoring studies about what might replace the gutted buildings, it was left to a private developer to seize the opportunity and actually finalize the plans, package the financing, and build the structure which would become the new Beale Street. Such is the theory of government and private enterprise working together for “urban renewal.” Needless to say, it is a partnership that often attracts opportunistic developers and often ends in legal arguments over who is reponsible for taking what risks. The Beale Street Project had its share of both problems.

The first private developer proposal came from Beale Street Blue Light, Inc., a consortium representing the financial leadership of the black community. Their proposal formed the basis for a WMC-TV documentary, Beale Street - Reclaiming the Blues, aired in September, 1971, and narrated by Art Gilliam, WMC-TV newscaster and head of the consortium. Beale Street Blue Light’s proposal differed little from its financing reflected the realities of a declining downtown, and favored “phased” rather than simultaneous development. According to BSBL, “it is economically unfeasible to place 45 businesses in downtown Memphis simultaneously with the expectation that each of them could survive in competition with each other, as well as with other downtown businesses.” Rather, it expected “to move into later phases of the project out of income generated by the initial phase.”6

No action was taken on the Beale Street Blue Light proposal while the MHA awaited completion of two feasibility studies. In January, 1973 — five years after it had begun destroying buildings — the Memphis Housing Authority formally announced that it was ready to accept proposals for the redevelopment of the three-block Blue Light area. MHA’s legal notice in the newspapers indicated that it was willing to consider any proposal, from rehabilitation of individual buildings by existing owners to the demolition of “all properties in the Blue Light area,” presumably including every building in the national historic landmark district!

By February, MHA had its eye on two groups — the black-led Beale Street Blue Light, Inc., and the whiteled Beale Street USA, Inc. The latter venture was headed by Ron Barassi, who described himself in his resume as a Vietnam veteran and a “mercenary platoon commander,” and a respectable bond salesman named Warren Creighton, whose company had handled housing authority bond issues in many cities. In contrast to Beale Street Blue Light’s program of phased development, Beale Street USA advocated a “simultaneous” approach modeled on Disney World, which would “finish the entire project and then open it to the public.”

A third group of developers brought together three leading Tennessee Republicans — white attorney and former Councilman Lewis Donelson, black attorney and businessman A.W. Willis, and US Senator Howard Baker. But Senator Baker withdrew his endorsement as he got more involved in the Watergate hearings, and the Donelson-Willis group never submitted a formal bid for redevelopment, though they were instrumental in creating the Beale Street Foundation the following year.

On April 12, 1973, Beale Street USA was chosen as redeveloper because the MHA board “felt like their management setup was better, their financial institution was better, and they wanted to do the whole thing at one time, not in a piecemeal fashion.” MHA chairman Ethyl Venson cast the sole dissenting vote, because she believed “there just really wasn’t the black involvement I think there should have been to develop Beale Street — I’m talking about people being on the investment end of the arrangement. I’m not talking about somebody just playing around or having their name used.”7 Mrs. Venson’s husband had had his dentist’s office on Beale Street for many years, so her feelings about the fate of the street were understandably stronger than the four whites who served with her on the MHA board.

Beale Street USA faced opposition from other leaders in the black community. In 1973, the Black Political Council organized “Concerned Citizens to Save Beale Street.” They vowed to fight the betrayal of their beloved street. Such organized opposition was short-lived, however, and incapable of sustaining the attention of community leaders and the media. But the ad hoc group’s campaign almost proved unnecessary because BSUSA quickly had more than enough troubles of its own.

In October, Ron Barassi talked in terms of $200 million for entertainment, conventions, tourists, and high-rise development, 1,000,000 square feet of entertainment and retail space, 600,000 square feet of office space, and a 300-room motor hotel. He promised that financing would be secured by February 1, 1974, and concluded by releasing a favorable economic feasibility study of the proposed project commissioned by his own group. A similar, yet more extensive study, done by Architecture Engineers Associates of Nashville (as required by the National Advisory Council on Historic Preservation), was much less optimistic: “Most of the buildings are in sad and deteriorated condition, and at least eight of the buildings still standing will have to be torn down, so that the ultimate cost of redevelopment will continue to rise beyond anticipated returns.”

One month after his confident announcement, Barassi cut his prediction about capital investment by half. By the following spring it looked as if he would not be getting a nickel. It was rumored that others had spoiled his credit with the banks; with no track record, and little visible evidence of financial solidity, Barassi was easily tagged as a bad risk.

On May 1, 1974, MHA asked Beale Street USA to surrender its development rights to the newly established Beale Street National Historic Foundation, chartered by the state as a non-profit corporation with quasi-public authority. In return, MHA would allow BSUSA to continue as “manager and operator” of the commercial portions of the street. This greatly reduced role was further threatened that summer, when BSUSA’s original contract neared expiration. At the urging of the Mayor’s office, MHA staff, and others, BSUSA was granted a final 60-day extension to secure financing. It failed again.

The waning of Beale Street USA accompanied the waxing of the new Foundation, conceived by the city’s chief administrative officer, Clay Huddleston, and developed by Lewis Donelson, Norman Brewer of the Downtown Council, and Ron Terry, the Chief Executive Officer of the First Tennessee Bank, Memphis’ largest financial institution. The Foundation initially consisted of a 33-member body for broad-based community participation, but was subsequently reduced to a 22-member body of 13 blacks and nine whites. Ron Terry headed the Foundation’s executive committee, and from the beginning, he and several other white committee chairmen dominated the meetings and set policy; the black board members tended to sit back and follow the leaders, no doubt awed by the head of a billion-dollar bank.

Beale Street had to sit and wait while the Foundation covered all the same ground again — plans, studies, reports, and decision-making all had to be repeated. Out came the architects’ renderings; up popped ideas for shops; back went the proposals to Washington for approval. This time, however, some of the rules had changed. First, ownership of the 12 acres in the Beale Street Historic District was conveyed to the Foundation. Second, under the rules of the Foundation, the land could no longer be sold to a redeveloper, but could only be leased from the Foundation, which was itself dependent on the City of Memphis for its operating funds.

In December, 1975, after delegating its responsibilites for development of the 12 acres of land parcels to the Foundation, MHA advertised for bids to repave Beale Street itself as a pedestrian, open-air mall. The Beale Street Mali’s design was consistent with the city’s Main Street Mall so the two could be tied together at the corner where the old streets intersected.

By this point, Beale Street’s redevelopment was being scaled down considerably, in the face of recessionary realities, to a mere $8.5 million for rehabilitation and construction of the buildings and $1.7 million to $2.5 million for a new parking garage. The project’s architect, Mel O’Brien, said that 282,000 square feet of space in the Blue Light area could cost between $25 and $35 per square feet to renovate — more than the cost of new construction.

Shortly after a low bid of $1.5 million was accepted for the construction of the Beale Street Mall, MHA announced that its design had been turned down by the National Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, which would block federal funds for the project. The Council complained that the proposed landscaping was too cluttered and lacked historicity; they said it would make Beale Street more like a suburban shopping mall than a turn-of-the-century street. News of the mall’s rejection came six years after the landscape architects’ firm of Ewald Associates received the $117,000 contract for its design.

MHA and BSNHF were understandably upset; a shopping mall design was exactly what they had in mind. They saw Beale Street with “a discotheque, a vaudeville and silent movie theater, two major theme restaurants, a book and music store featuring blues and soul music, a recreated Pantaze Drug Store, an art gallery, and an all-cotton products outlet.”8

To this day nothing has been redeveloped, though MHA has spent an estimated $23 million on the Beale Street area acquiring land, demolishing buildings, putting in new streets, curbs, gutters, sewers, and lighting, and paying the salaries of those who serve as administrators, consultants, architects, and other accomplices. But there are still monthly developments which indicate the sad tale of Beale Street isn’t finished. In the summer of 1976, for example, Beale Street USA announced it would sue the Foundation for outstanding payment due for “services rendered”; at the end of 1976, BSUSA was bought off for a mere $100,000 to release the City from its original developer’s contract, worth about $3 million. Yet another round of studies has been commissioned, including a “pre-feasibility study” by the American City Corporation.9

The land around Beale Street remains vacant. MHA has posted huge signs: “Commerical Land For Sale,”10 It has also mailed all over the country a brochure proclaiming, Remaining Urban Renewal land ready-to-develop for commercial, industrial or residential uses in Memphis, Tennessee. The 28- pages describing unsold parcels features black outlines around empty white space, representing vacant weed-grown land that was once houses, trees, small businesses, gardens, historic buildings, lots of nice people, and some of the world’s greatest music.

FOOTNOTES

1. W.C. Handy, Father of the Blues (N.Y., 1941, 1970), p. 95.

2. Gilmore Millen. Sweet Man (N.Y. 1930), pp. 150-1. See also “Amateur Night on Beale Street,” Scribner’s (May, 1937).

3. In its first urban renewal project on Railroad Ave., MHA cleared 41 acres and built three large buildings — a school, a warehouse and a bowling alley. The rest of the area is still vacant.

In the Jackson Ave. Project, also begun in 1956, MHA cleared 120 acres for use by institutions — a vocational school, a fire station, city engineering offices, and additions to two hospitals. The land was thus removed from the tax rolls. The balance of the land went for light industrial uses and right-of-way for the new 1-40 expressway.

Similarly, in the Medical Center Project, begun in 1958, 140 acres of solid 1920s apartment buidings were razed at a cost of $17 million for about $40 million in new hospital and medical school developments, also mostly tax-exempt.

The Court Ave. Project, begun in 1960, built the new Civic Center at a net cost to the MHA of $12 million.

4. Press-Scimitar (September, 26, 1966).

5. Commercial Appeal (August 28,1968).

6. Undated memo from BSBL, Inc., to Drue Birmingham, MHA Real Estate Dept.

7. Evidence that Art Gilliam’s group could have been a better choice as a redeveloper came in 1977 when he purchased the high-priced Memphis radio station WLOK, making it one of the country’s few black-owned AM stations.

8. Commercial Appeal (March 22, 1976).

9. A subsidiary of the Rouse Company that almost developed 4600 acres of Memphis’ Penal Farm. See “How to Stop the Developers,” Southern Exposure (Winter, ’76).

10. One of the few beneficiaries of the Beale Street land clearance program has been the Memphis Publishing Company, owner of the city’s only two large-circulation dailies, which bought a large chunk of land at the eastern end of Beale for its new plant and office-expansion. Perhaps this is why the newspapers in Memphis have been so soft-spoken about urban renewal.

Tags

David Bowman

David Bowman is a contributing editor on architectural and urban affairs for City of Memphis magazine, and is a member of the Beale Street Foundation’s cultural committee. This article is adapted from a chapter in his book now in preparation, Memphis and the Politics of Development. (1977)