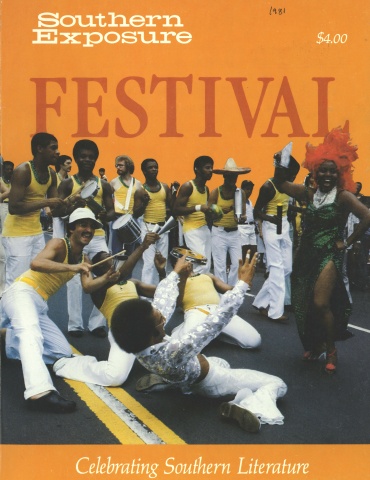

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

The awarding of the Premio Casa de las Américas to Rolando Hinojosa in 1976 for a chicano novel, Klail City y sus Alrededores, shook to awakening the U.S. literary world. The Premio is to Latin America what the Pulitzer is to the U.S., and this international literary award has never been taken lightly by those at the forefront of world literature. Chicano literature, on the other hand, has frequently been taken lightly in the U.S. literary world, and major language associations have hesitated to accept it as an appropriate area for research and attention.

This disregard did not surprise those who had for years alleged that “world literature” classes in U.S. colleges and universities reviewed to excess the literatures of England, France and Germany while ignoring the rapid succession of innovations in style and thought surging out of Latin America (and the rest of the Third World and U.S. minorities). Curiously enough, this occurred while literary critics in France and Germany were focusing on modern Latin American masterpieces and begging for more. The entire situation taken into account, it was hardly shocking that U.S. critics argued that chicano literature was not “quality literature” and that they based this finding more on what they heard than on what they read.

The Premio-winning Klail City (later released in the U.S. as Generaciones y Semblanzas) was not the first chicano obra (work) of its kind. For years, those in chicano circles had praised the sensitivity of Rivera’s And the Earth Did Not Part and the character development of the haunting protagonists of Bless Me, Ultima. For years, chicano writers and readers had admired the dramatic texture of Estela Portillo Trambley’s Rain of Scorpions and the mestizaje (blending) of worlds, languages and concepts in poetry by Alurista, Lalo Delgado, Ricardo Sanchez and Angela de Hoyos. The unforgettable poetic figures of La Jefita and El Louie in the work of Jose' Montoya epitomized cultural realities, and the chicano reader responded with a fervent “Los conozco.” (“I know these people.”) These early favorites reflected and defined the characters of the barrio, and we could all appreciate and see the pachuco-turned-soldier-turned-pool-hall-hero, “with all the paradoxes del soldado raso — heroism and the stockade.”

And on leave, jump boots

shainadas and ribbons, cocky

from the war, strutting to

early mass on Sunday morning.

“Wow, is that ol’Louie?”

“Mire, comadre, ahi va el hijo

de Lola!”

Afterward he and Fat Richard

would hock their Bronze stars for pisto en el Jardín Canales. . . .

Often for the first time in their literary lives, chicano readers would recognize characters from their cultural context — not stereotyped humble peasants and Hollywood hoods and revolutionaries, but guys from just down the street who were, after all, just “el hijo de Lola” (“Lola’s son”) hocking their war medals for something to drink. Heroic-tragic figures whose lives fell short of what society asked of them and whose dreams far outreached what society could offer them.

Amidst the everpresent criticism that the mixing of English and Spanish reflected a linguistic deficiency (of “cultur ally deprived” individuals), linguistic masterpieces continued to be woven from the beauties and strengths of both languages. Doubled possibilities for alliteration and double entendre were found in concentrated melanges of Spanish, English, “Texan,” Black English, even Mayan and Nahuatl word concepts. Imaginations exploded beyond limits, beyond conventions, beyond even our own beginnings.

Regional chauvinists continued to criticize our “Tex-Mex” and to treat it as a “language deficiency” caused by low educational or intellectual levels. And chicano writers continued to indulge in “language play” as an inventive and intriguing challenge for linguistic creativity. What had begun with reflections of our own bilingual reality — my own “me senté allí en la English class” and Delgado’s “Chicotazos of History” — turned into the formulation of totally new grammatical styles. Lexical creations sprang from an awareness of our own dually bilingual existence and from the discovery of new worlds of thought and literature — the Mayan, the Aztec, the Native American and so forth. Formerly we would, in our daily lives, hispanize English realities: “I missed” would resurrect in Spanish as “mistié;” “I flunked” would expand the traditional lexicon with “flonquié;” and the “big, old thing” ending “azo” would turn a party in an English sentence into a porazo in a Spanish conversation. Now, those same traditions of interlanguage play would apply to the newly discovered language heritage. Acutely aware of the sounds of English, we would accent our Spanish to a mock-anglicized “free wholes” (for frijoles) and then play the reverse by accenting our English with the sounds of Spanish: pino borra for “peanut butter.” Now, reading through Aztec accounts of teotl, mitotl, coatl, tomatl, we exclaimed, instead of the commonplace “Qué loco!” (“Crazy!”) “Qué locotl!” And the new mestizaje of language yielded concentrated high-impact packs, like the three-word label of the moon by Victoria Moreno — “vanilla, canela crescent.”

The juxtaposition in selection of English, Spanish or a combination of both adds to the power of each word and to the entire verbal context. Some works are, by necessity, in English, utilizing the compact, business-like high-powered impact of each short jabbing word. The following poem by Sylvia Chacon is an excellent example of this style of writing and of the visual arrangement of the words. The format, together with the words themselves, seems chopped up like little pieces of spaghetti so that the meaning comes out not only from the context of the language but also from the shape and texture of the poem itself.

I am

the jealously entangled

spaghetti

you abstained

from eating

because

I

refused

to be knifed

and forked along

in your eagerness

to get

the

meat.

The eloquence of Reyes Cardenas’ Poema Sandino was deliberately woven in an all-Spanish fabric. The profound personal sentiment, the political intent, the entire Spanish speaking world’s contemporary political context add to what is already one of the most powerful statements ever made in chicano poetry. An excerpt:

estas cosas que nos arrastran por el piso

tenemos que pararlas como un arbol seco de navidad

tenemos que echarle agua hasta que le salgan hojas

hasta que podamos hablar otra vez

hasta que podamos mover al siglo . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

pero nosotros, no so tros tenemos que resistir al tiempo

levantar la pluma aunque sea con huesos

tenemos que ofender a los que cierran los ojos

que hasta paginas vacias ahoguen sus suehos dulces

que despiertan tosiendo buscando aire.

Translation, in poetry, is a dependent and limited form of expression. But, with apologies for this sacrilege, I offer this translation of the segment quoted:

these things that drag us across the floor

we have to stand them up like a dried-up Christmas tree

we have to sprinkle water on them until they sprout

leaves

until we can speak again

until we can move the century . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

but we, we have to resist time

lift the pen, although it be with our bones

we have to offend those who close their eyes

that even empty pages drown their sweet dreams

who wake up coughing searching for air.

Language mixture is an art as surely as any other manipulation of words, as evidenced in the beautiful flow and rich image-laden texture of the first few lines of “Mis ojos hinchados”by Alurista.

Mis ojos hinchados

flooded with lagrimas

de bronce

melting on the cheek bones

of my concern

razgos indígenas

the scars of history on my face

and the veins of my body

that aches

vomito sangre

y lloro libertad

. . . . . . .

The early stages of chicano literature were full of identity assertions: “I am Joaquin, lost in a world of confusion,” or “I am a Quetzal who wakes up green with wings of gold, and cannot fly,” or “I am the Aztec Prince and the Christian Christ,” or “I do not ask for freeeom — I am freedom.” But chicano literature has gone beyond its beginnings. It no longer simply asserts and defines an identity. It now paints its context, and carries out its' visions. The identities of crazy gypsy, Aztec Angel, Mud Coyote and Crying Woman of the Night now go beyond their own definitions to live out their lives in the more fully developed mythological and social context of chicano literature.

The symbols and images have already become familiar — we speak a common mythological language. Critics such as Juan Rodriguez, Max Martinez and Jose Flores Peregrino have begun to explain and nourish the literary symbols. Flores Peregrino identifies and substantiates motifs, visions and symbols such as the mirror (symbol of self-knowledge), the creative serpent, in lak ech (Mayan principle of behavior) and, of course, the parent earth, la tierra, as birther, burier and healer. With a critical base for study, chicano literature can no longer be ignored by those unfamiliar with its symbols and settings.

The voice of the chicana poet and writer, the woman, is a strong one within this stream of expression. The powerful work of Margarita Cota-Cardenas, Evangelina Vigil, Estela Portillo Trambley and countless others provides a counterbalancing and whole image of our entire culture, not just the male perspectives of it. The chicanas remind us emphatically and eloquently of the healthy duality of indigenous cultures, in which the Creative Spirit is both a Mother God and a Father God, combining these two aspects of its reality in its power and sustaining spirit. Legendary Mexican figures, such as La Llorona, La Virgen de Guadalupe and La Adelita echo feminine voices of pain, protective power, action and valor. Real predecessors in chicana and Mexican history provide strong character bases for modern writers — women soldiers, colonels and a general in the Mexican Revolution, outspoken female intellectuals and writers, the everyday community roles of women leaders in our barrios who are curanderas (healers), political organizers and businesswomen. These images are reflected in our obras.

Yet the writings are not merely covered with roses and adulations. The awareness of sex-role oppression voiced loudly by the poet Sor Juana Unes de la Cruz in the 1600s is carried on by the modern chicana writer. A strong feminist protest of the treatment of human beings as objects to be bought and sold and owned is evident in the mischievously potent poem by Margarita Cota-Cardenas, who knowingly epic-izes one woman’s life in the not-too-subtle image of a flower.

SOLILOQUIO TRAVIESO

mucho trabajo ser flor

a veces

solitas

y en camino

concentramos muy fuerte así

arrugamos la frente

para marchitarnos antes

y al llegar al mercado ji ji

no nos pueden vender

And, again, in poor but sincere translation:

MISCHIEVOUS SOLILOQUY

it’s a lotta work being a flower

sometimes

all alone

and on the road

we concentrate real hard like this

we wrinkle our foreheads

so we can wither before we get there

and when we get to the marketplace hee hee

they can’t sell us

The unconquerable independence of the statement is but one example of the eloquence in chicana poetry. Most of these works speak not only to the oppression of human beings for reasons of gender, but also for reasons of color, culture, language, accent and philosophy. They protest the limitation of human beings’ rights to full autonomy and personal development. It is a natural connection, for racism and sexism are simply different verses of the same song.

In short, chicano literature has gone beyond beginnings in many respects — it has gone beyond a definition of our cultural origins, it has gone beyond the beginning stages of myth creation and symbol kinship, it has gone beyond its own awareness of the literary action itself, and perhaps most significantly to those who struggled for years to be read and to read — it has gone beyond the beginnings of its acceptance and recognition by the literary world as a whole.

Warning

By Carmen Tafolla

Don’t smell the smoke of a brown ghost

who keeps starving white

and dying brown.

He causes mitotes like a Texan Indian

and then goes through the winter

sucking on cactus skins and searching

for overlooked mesquite beans

gone brown.

Instead he finds Spanish missionaries too

eager to adore him, and nations too

foreign to respect him, and only one

or two

mesquite beans.

Medecine Poem

By Carmen Tafolla

March 9, 1981

Sickness lies around us like rotting feelings

splintering minds on the spears of a bored and

angry crowd

and splattering the faces of children with blood.

Sickness robs bandages to pay bombs

and build better rockets, better than those better

in a winning-game that never wins.

Sickness nabs young black children playing in

Atlanta

and lays their empty bodies, laughingly, by the

road

to match the brown notches in policemen’s guns.

Sickness leaves health hiding in a grass-roofed

shack

in a Kickapoo Indian village

under the international bridge that holds

Eagle Pass, Texas to Piedras Negras, Mexico

where native peoples between two foreign

nations

use dual citizenship

to ward off dual dangers.

And health huddles, hides, in healing huts

of cardboard and grass,

never knowing which way to go to escape

the madness.

Our hurting and our healing must run in the

right direction

and swiftly, with quick looks backwards,

carrying with it always the medecine pouch,

intact, with human bonding.

For wars

and poems

must always

have an end.

Tags

Carmen Taffolla

Carmen Tafolla is the author of To Split a Human: Mitos, Machos, y la Mujer Chicana on Chicanas, racism, and sexism, published by the Mexican American Cultural Heritage Center of the Dallas Independent School District. (1986)