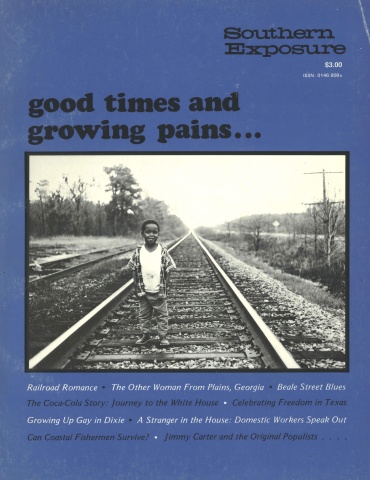

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 1 "Good Times and Growing Pains." Find more from that issue here.

Asking Jimmy Carter, as John Chancellor did recently, if his reputation wasn’t derived more from his use of symbols than his actual accomplishments is a little like asking Coca-Cola if its success isn’t more the result of its advertising than the actual merit of its product. “Well, John,” Jimmy drawled, “I don’t think you can really separate the two.”

Indeed you can’t. Or at least, Mr. Carter is in big trouble if you do. So is J. Paul Austin, the chairman of the Coca-Cola Company. No other company or President has succeeded so well solely on the ability to manipulate images. The image is the product. What you get is what you believe you get. The consequences of a Presidency controlled by a master of the art of deception is one thing (see below: “The Politician as Magician”); but understanding the workings of a corporation built on images is something else again. Presidents come and go, but Coca-Cola was built to last forever. Forever.

It didn’t start out that way, of course. For decades, Coke was in many ways the same sort of outsider that Carter was in 1976. Starting out in Atlanta in 1886, it pulled itself up by its own bootstraps, relying largely on the Southern kinship network of its founder, Asa Candler, and his first bottlers. As the fame of the drink grew, so did the fortunes of dozens of Southern families, who in turn financed ventures ranging from Delta Air Lines to Alabama’s Bellingrath Gardens to the Atlanta Roadway track; in time, the product propelled its makers into the top circles of national power, reflected today in J. Paul Austin’s positions as chairman of the Rand Corp., director of Morgan Guaranty Trust and General Electric, member of David Rockefeller’s Trilateral Commission, regent of the Smithsonian Institution, and trustee of a dozen organizations from the California Institute of Technology to the Nutrition Institute. To achieve such distinction, the men who ran the company realized even in its early years that the most important thing about their product was its good image. In the first year, they spent as much money in public relations as they earned in profits, a trend that has continued into the present when both figures hit $200 million.

Everything depended on the reputation of Coke, and like Carter’s people, the men behind Coca-Cola knew they had to make the drink respectable to the skeptical yet gullible constituent. “We can’t afford to offend the sensibilities of any group of people anywhere,” quips a senior vice-president in Atlanta. “We stand for the very highest quality Clean-cut, up-right, the family, Sunday, the girl next door. Wholesomeness.”

Selling wholesomeness is what Coca-Cola is all about. The product couldn’t be perfected; only the image could be manipulated to make the drink more and more popular. And when it comes to images, Coca-Cola literally wrote the book. A sampling from its in-house pamphlet, Philosophy of Advertising: “Only [through advertising] can we gradually ‘condition’ our customers to a point where they are favorably reminded of the product when they see a simple trademark at the point-of-sale .... If what we say is to make its impression, it must be repeated many times. One drop upon a stone leaves no impression, but many drops and the stone is worn away.... Because Coca-Cola is bought on impulse and because we have no way of telling when and where an impulse will take hold on a customer and because that impulse will be momentary in its duration, we must aspire to so arranging our advertising as to always present an appealing invitation to ‘pause for a Coke’ whenever and wherever an impulse strikes any of our customers.”

By succeeding in that task, the wizards behind Coke have transformed what is essentially colored sugar water into a fountain of wealth, gushing forth more millionaires than any other product in history. They have turned a one-man operation into a multi-billion dollar corporation that owns orange groves in South Africa, bottles wine in New York State, sells sewage systems in Canada, trains management specialists in Washington, cans protein drinks in South America, peddles bottled water in New England, makes instant coffee in Europe, and ships to 135 countries the magic ingredients of its mainstay product: the Fabulous Coca-Cola. The company and the product now have credentials that boggle the mind:

world’s largest consumer of granulated sugar

world’s largest privately-owned truck fleet

world’s most advertised product

world’s biggest retail sales force

world’s leading producer of citrus concentrate

world’s most extensive franchise system

world’s first multinational corporation of consumer products

world’s best known product

world-wide supplier of private-label coffee and tea

How the masters at Coke built their empire, and how they conquered the multitude of unbelievers, imitators, and challengers surrounding them, is a story worthy of a book (and I’m working on that now). It is a story of the power of men and money to control what you think, to generate a blend of images that captivate your imagination, that will make you think ‘Coke’ when you see a sign or feel tired or thirsty or a little depressed (“Coke adds life”). It is a story of the most incredible mobilization of human energy for trivial purposes since the construction of the pyramids. Think of it. The world’s most highly advanced team of writers, public relations experts, psychologists, lobbyists, lawyers, sales managers, and advertising executives are focusing all their creative talents on getting young kids addicted to Coke so they’ll drink it for life.

It is the story of what went wrong with the American dream.

Chapter I

Coca-Cola was born in the 1880s in a period of intense competition known today as the era of the Robber Barons. Ruthless men of wealth carved up one industry after another, hoping to acquire monopoly profits. John D. Rockefeller did it in oil, Andrew Mellon went after aluminum, Buck Duke succeeded in tobacco, Jay Gould and a few others took the railroads, Andrew Carnegie tried for steel. Coca-Cola had its strong man, too, and it typifies many giant corporations which, despite public mythology, are still led by a single strong man. The story of Coke is in many ways the story of two generations of strong men.

The first of this mighty pair was Asa Griggs Candler. Cut from the humorless, Puritan mold of a religious mother and stern, hard-driving father, Candler pushed himself and his product from the obscurity of an Atlanta drugstore basement into national prominence. The Civil War had left Candler’s prosperous parents and their sprawling west Georgia farm in disarray, but young Asa was able to use the connections of the Candler clan to secure a job as an assistant druggist in nearby Atlanta. In 1873, at the age of 21, he arrived in town with the proverbial $1.75 in his pocket — the beginning, according to Coke legend, of “the entrepreneurial spirit that makes the company strong.” But with a cousin who had served as Georgia’s governor and two brothers who went to the US Congress, Asa Candler was not about to fall on his face. In rapid succession, he “worked” his way up to chief clerk of the store, married the boss’ daughter, opened his own drugstore, and began dabbling in the booming real estate market of a rebuilt Atlanta.

It didn’t take Candler long to recognize that the real money in drugs came not from owning a store but from selling your own concoction through other people’s stores, or through the ubiquitous traveling medicine man. With his savings, Candler launched his own product called Botanic Blood Balm and plunged into the greatest merchandising circus America has ever witnessed: the amazing patent, or proprietary, medicine boom — “cure-all remedies for all that ails thee.” His appetite was just whetted when he heard of a new idea for a headache and hangover tonic called Coca-Cola.

Doc Pemberton, an obsessive creator of spirits and pharmaceutical wonders, had invented Coca- Cola one day in his back yard. He was searching for a new “lift-giving” medicine that he could add to his line of compounds distributed to Southern drugstores by his John S. Pemberton Chemical Company, compounds like Globe of Flower Cough Syrup, Indian Queen Hair Dye, and Triplex Liver Pills. On that spring day in 1886, Pemberton took his patented French Wine Coca (an “ideal nerve and tonic stimulant”) and replaced the wine with a pinch of caffeine, a little cola extract, and a mixture of a few other oils. He was delighted with the result. By the end of May, Pemberton had convinced a few Atlanta druggists to feature his creation, and he placed his first ad in the local newspaper heralding the product as “Exhilarating! Invigorating!” It wasn’t until six months later that he discovered by accident that the medicine tasted better with carbonated water than plain tap water. By the end of 1886, Pemberton had earned $50 in profits on 25 gallons of Coca-Cola syrup and had spent $46 in advertising.

Gradually, the drink picked up sales, but Pemberton’s health was rapidly declining, as were his finances. He began casting about for partners, and Coca-Cola immediately became something of a hot potato among Atlanta druggists seeking a good investment. No one quite knew what the future held for a health drink that tasted good. Soft drinks were hardly known, and the proprietary medicine field was already crowded. Nevertheless, it seemed to sell well, perhaps because of its unique combination of properties that made it a pleasant-tasting stimulant. Pemberton’s assistant, Frank Robinson, had named it Coca-Cola for its major ingredients derived from the coca nut and cola plant leaf (and his hand-written rendering of the name remains the product’s trademark). No one seemed to worry about whether or not the drink contained cocaine — it probably did. (The official company position is that “nobody knows about then, but it’s sure not in there now.”) Besides, the caffeine — equivalent to a third-of-a-cup of coffee — and the phosphoric acid’s conversion of sugar to readily digestible levulos and dextros was enough to give Coke its lift-giving kick (as well as its ability to dissolve nails). Whatever the real reason, the druggist-investors knew the product worked, and they were willing to gamble on its attractiveness in the hustling, yet melancholy days of the New South.

Since Asa Candler had personally found relief for his habitual headaches from a glass of Coke, he recognized the drink’s value. And since he was a shrewd businessman, he quickly moved into the center of the financial transaction surrounding Pemberton’s dispersal of his interests in the Coca- Cola formula. In two years, Pemberton had completely sold out, and Candler had made $300 by loaning money to various investors, then buying up their interest himself or helping another investor buy it at a higher price. By August 30, 1888, the broken Pemberton was two weeks in the grave and Asa Griggs Candler had purchased full ownership of the properties, titles, patents, formula and assets of the “proprietary elixir” Coca-Cola for the modest sum of $2,300. Rumors still abound in Atlanta that Candler as much as stole the formula from the aged Pemberton. The word “hustle” may be fairer. A more generous account is given by Candler’s son in his father’s official biography: “Dr. Pemberton was apparently a very capable druggist, but his business enterprises were never crowned with conspicuous success, and it remained for others to make his creation known all over the civilized world.”

No one would question Candler’s business ingenuity. By 1890, at age 38, the father of five children, Candler was grossing over $ 100,000 a year, chiefly from the sales of his Botanic Blood Balm, Coca-Cola, and Everlasting Cologne. Coke sales were growing so rapidly, and appeared so limitless, that Candler decided to close out his entire stock of “drugs, paints, oils, glass, varnishes, perfumery and fancy articles” in order to concentrate on one product. In the next two years, he moved to a new building, incorporated The Coca-Cola Company with himself as president and major stockholder, and devised an ambitious advertising campaign stressing the “delicious, refreshing, stimulating, invigorating” nature of his drink.

The new company’s advertising budget and gallon sales of Coke skyrocketed tenfold in each of the next two decades, from $11,000 and 35,000 gallons in 1892, to $120,000 and 360,000 gallons in 1902, to more than $1 million and 4 million gallons in 1912. That year, Coca-Cola was sold in every state in the US and several foreign countries; it had earned the distinction of being the most advertised product in America, and had made Candler a millionaire many times over.

Candler’s success had much to do with his niggardly habits (he saved used envelopes for scratch paper) and his insistence that all employees abide by “my views of what is the proper moral behavior that should be associated with Coca- Cola”; but the cornerstone of his business acumen was his stubborn concentration on perfecting the techniques of mass marketing and advertising. He tried every known gimmick, and invented a few himself, to get his product into drugstores and into the hearts of a buying public inundated by such merchandising innovators as F.W. Woolworth and J.C. Penney. Candler’s thoroughly prudish instincts balked at the use of scantily clad women in his advertisements, but he held back nothing when it came to making claims for his “wonderful nerve and brain tonic.” With the help of his nephew, Samuel C. Dobbs, who headed the company’s advertising program for decades, he let loose an avalanche of new slogans attributing extraordinary medicinal qualities to a 6V2 ounce glass of Coca-Cola: “relieves physical and mental lethargy,” “for headaches and tired feeling,” “refreshes the weary, brightens the intellect, clears the brain,” “strengthens the nerves,” “the favorite drink for ladies when thirsty, weary, and despondent,” “remarkable therapeutic agent.”

Ironically, Candler strenuously objected to the government’s right to tax Coca-Cola as a proprietary medicine during the Spanish-American War, even though Coke ads had claimed it could cure such maladies as hysteria, neuralgia, melancholy, biliousness and insomnia. With the help of his lawyer brother John — who was the company’s general counsel and an associate justice of the Georgia Supreme Court — Candler sued the federal government for $ 11,000 in back taxes. At a jury trial in 1902, Candler won back his money with $2,000 interest.

But stressing Coke’s medicinal qualities had more drawbacks than the dreaded intervention of the government taxman. Candler and Dobbs began to realize that it limited sales to those people looking for relief from some specific discomfort. While there were plenty of people feeling miserable in the early 1900s, the routines of their daily lives demanded a wholly different remedy than anything yet imagined. The rise of the assembly line, the big city and cash in the pocket were in sharp contrast to the world of the family farm that had dominated American culture only a generation earlier. The country was undergoing a revolution in life style that systematically turned self-sufficient people into wageworkers and consumers, and with the agony of that transformation came the need for new mechanisms of relief. Populism, evangelical revivals, unionization, socialism, reactionary movements fueled by racism and nativism all experienced a boom in the period from 1880 to 1920. Coca-Cola offered something different. It didn’t confront the changes; it made them easier to endure; it projected an image of the good life that came with “the pause that refreshes.” For only a nickel, it offered a pleasant escape into a fantasy world of pretty girls, warm friends and wholesome fun.

Today, we are bombarded so often with such image advertising, including Coke’s ads which associate the drink with everything from falling in love to world harmony, that we take the technique for granted; or put another way, advertisers now largely determine what we conceive of as satisfying, convenient, good, responsible, valuable and fun. But in the early 1900s, when quick things that made you feel good — especially sex and booze — were given the Victorian frown, Coke was taking a bold move to pioneer a market for itself as “a delightful surprise” (1924). Ever so cautiously, Samuel Dobbs altered the emphasis of Coke’s ad copy from pragmatic cure to fantasy delight, from “specific for headache” (1893) to “relieves the weary” (1905) to “full of vim, vigor and go” (1907) to “the drink that cheers but does not inebriate” (1908) to “when life and energy seem to be oozing out of your pores with each drop of perspiration and it just seems you can’t go a step further or do a lick more of work, step into any place and drink a Coca-Cola. You’ll wonder first what turned on the cool wave....” (1910) to “enjoy a glass of liquid laughter” (1911) to “its fun to be thirsty when you can get a Coca-Cola” (1913).

In the decades ahead, the trend escalated and soon the words became less important than the scenes of happy smiles. The astronomical growth in Coke sales proved that Candler and his associates had created a market for “the great national drink” that satisfies “the heart’s desire” (1916). They had only to get their product out to the masses and maintain their lead over any new entries in the field. The second task of keeping the upper-hand against any would-be competitors was helped by a vigorous legal campaign against upstart soft-drink companies that said things Coke now regarded as deceitful. Truth in advertising had not yet taken hold in America, but as Coke’s name became established, along with the names of Wrigley and Hershey and Camel, a new impulse for honesty in advertising arose among America’s leading merchandisers. A host of newcomers like Taka- Cola, Polo Kola, Vera Cola and Chero-Cola were capitalizing on slogans created by Coke to win a share of what Candler thought was rightfully his market. Competitors became “imitators” and John Candler and the company’s legal department sued hundreds of them, successfully setting precedent after precedent in the new field of trademark law. Pepsi-Cola’s right to use the “cola” ending finally broke Coke’s monopoly on the word.) Meanwhile, Samuel Dobbs traveled across the country preaching the virtues of honest advertising; in 1909 he was selected president of the Associated Advertising Clubs of America (predecessor of the American Advertising Federation), and in 1911 his “Ten Commandments of Advertising” became the industry’s standard for decent propaganda. From the purveyor of phony promises, Coke proudly elevated itself to “the leader in truthful advertising.”

The task of getting the product out to the masses was also handled by a Candler relative. Nephew Daniel C. Candler went on the road with a horse and buggy to peddle Coke, and in 1894 went to Dallas to open the company’s first branch office. Asa’s sons worked in the Atlanta production center, which, for the first few years, was hardly more than a large kettle in which the ingredients were mixed. One ,son supervised the operations in New York and later introduced Coca-Cola to London. Candler even imposed on his brother Warren, who became the ranking bishop in the Southern Methodist Church, to distribute coupons for free drinks to local druggists in his home base of Nashville. (Asa and Warren’s invasion of Cuba on behalf of Coca- Cola and Christ is described in the Fall, 1976, issue of Southern Exposure.)

Coupons, trays, outdoor billboards, metal signs, wall paintings, soda fountain urns, clocks, calendars, matchbooks, and all manner of decorative displays were employed by Candler’s growing sales force to entice druggists to dispense the product from their fountains. In addition, the bottling of Coke begun by a pair of Chattanooga businessmen in 1899 rapidly expanded into an elaborate, and thoroughly incestuous, franchising network.* Even though the network operated independently of his money or directives, Chandler kept his eye on the bottlers by maneuvering another nephew into a position of coordinating their internal relations 1923 magazine ad 1941 calendar through publication of The Coca-Cola Bottler. As business mushroomed, the Coca-Cola Company opened more field offices to service its expanding market, and Candler satisfied his fascination with real estate Äby generally building a “Candler Building” in each new city: New York, Baltimore, Havana, Toronto, Kansas City, Los Angeles — the list kept growing.

As one of the richest men in the South, Candler found himself increasingly involved in real estate, politics and philanthropy. In 1914, when World War I broke out and the bottom fell out of the cotton market, he single-handedly bailed out the region by establishing his own crop-support price for farmers; he built huge warehouses in Atlanta and offered to loan any farmer six cents per pound for the cotton they stored with him. Candler’s Central Bank & Trust began shelling out $100,000 per day, and promised to loan out $30 million if necessary. The farmers never fully tested this promise, however, since America’s build-up for the war soon brought cotton prices back up. Nevertheless, as a local newspaper reported, “The system under which the Atlanta Warehouse Company is operating will eventually revolutionize the marketing of cotton and will finally do away with the ruinous system of selling the entire crop at harvest time for what it will bring on a glutted market.”

The popularity of Candler’s program to help the little farmer made him a natural choice when Atlanta’s business elite began looking for one of their number to run for mayor in 1916. The city, as Candler told his son, was “financially and morally bankrupt” and needed an energetic “chief executive of this corporation.” Candler was also becoming more aggravated with “federal legislation adverse to accumulation of surplus [capital] .C Until 1915, wrote his son, “in a very real sense, the Coca-Cola Company was Asa G. Candler, and the line between his personal property purchases and those of the company was frequently faintly defined.” The new federal income statute ended all that, requiring the company to divest itself of its nonrelated real estate holdings. In late 1916, Coke distributed over $6 million in property to its stockholders, and a few months later, Asa G. Candler, Inc., was formed to hold Candler’s vast assets.

At age 64, Candler turned over the reins of the trimmed-down Coca-Cola business to his sons and, having won the mayoral race, began administering the city as though it was his personal fiefdom. He defeated a union engineer from Southern Railway who mounted a sizable campaign (winning 35 percent of the vote) against Candler’s anti-labor practices. But Candler’s belief in the wisdom of an elite was only reinforced. Shortly before his term ended, he lectured his fellow citizens on the dangers of how “a democracy runs quickly to anarchy”:

“When the world is made safe for democracy, it will still remain for us to make democracy safe for the world. A rapid, ranting democracy which has taken leave of all settled principles of right and silenced the voice of conscience is about as unsafe a force as can be imagined, and the raising of such democracies is the peculiar peril of cities without both intelligence to know what is right and virtue to do the right that is known.”

It was precisely this blend of moral and corporate rhetoric that would dominate the Trilateral Commission upon which J. Paul Austin and Jimmy Carter sat decades later.

While Candler continued a number of projects, including the development of the Druid Hills suburb and Emory University, his lackluster sons began to wonder if the Coke business had not reached its maximum potential. Competitors were successfully invading the market, the Coca-Cola trademark was still not securely protected by law, the price of sugar that had skyrocketed during the war refused to drop, and a suit filed against the company under the Pure Food and Drug Act threatened the very formula of their beloved product.

This last development was especially menacing to the Candler family. When the Pure Food and Drug Act went into effect in 1906, the man in charge of its enforcement, Dr. Harvey Wiley, began publicly calling the makers of Coca-Cola “dope peddlers” (“dope” is still slang for Coke in the South) and “poisoners.” In 1909, he had a shipment of Coke syrup seized on its way to Chattanooga. In the resulting trial, US v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, one court after another considered Wiley’s charges that the new law prohibited additions of caffeine to the product and prohibited further use of the drink’s world-famous name since it contained no coca and little cola. Company lawyers argued that caffeine was not an additive but an essential part of the drink, and that many products from pineapples to Grape- Nuts didn’t contain derivatives of the substances mentioned on their labels.* The battle raged for years, but by the time the Supreme Court ordered Coke to obey the Act, Dr. Wiley had been replaced by a less aggressive administrator, who let the company off the hook in 1918 with a small modification in their manufacturing process and a bill for legal costs of about $90,000. Nevertheless, the anxious Candler sons had already begun negotiations, and in 1919, in the largest financial transaction the South had yet known, the Coca-Cola Company was sold for $25 million to a consortium backed by three banks: Chase National and Guaranty Trust, both of New York City, and Atlanta’s Trust Company of Georgia.

Thus ended the first epoch of Coca-Cola’s history. As Asa concluded: “When I gave them [his four sons] the business, it was theirs. They sold out a big share for a fancy price. I wouldn’t have done that, but they did, and from a sales standpoint, they drove a pretty keen bargain.”

The moving spirit behind the new owners of Coca-Cola was Ernest Woodruff, a man every bit as shrewd and expansive in his operations as Asa Candler. As president of the Trust Company of Georgia, he had helped launch several businesses that continue today, including Atlantic Steel Company, Continental Gin, and the predecessor of The Mumford Company. But Coke was already well established, and when its new owners decided to get a new president in 1923, they asked for Ernest’s prime creation: his son Robert.

Robert Winship Woodruff quickly became a living legend. He had already worked his way into the presidency of Cleveland’s White Motor Company, and for a few years continued in the post while also serving as president of Coca-Cola. He was 33 in 1923, when he took charge of Coca-Cola, and he has never really given it up; at age 87, partially disabled by a stroke, he still goes into his office in Coke’s headquarters whenever he’s in Atlanta. Visited there recently, he talked about Coke chairman J. Paul Austin and president J. Lucian Smith, the business-college types who are transforming the company from a personal extension of first Candler and then Woodruff into a sophisticated, diversified, management-team-centered corporation that can better compete in the modem business world. As he looked at their pictures across his desk, Woodruff noted that “he had hired them,” and with a characteristic twinkle, added that although he doesn’t interfere in management, they keep their jobs “as long as they do what I like.” As chairman of the board’s finance committee and controller of roughly 20 percent of Coke’s stock, Woodruff is in a good position to see that the transition of power to a new generation is smoothly executed. Most of the board members of Coke have been his personal friends for decades: of the 18, only two are not Southerners or company employees; one-third are over 70 years old.

Asa Candler actively directed Coke for 24 years; Woodruff headed its growth for more than half a century. Everything Candler did, Woodruff did bigger and better. His exploits broadened the company into an international financial power and thrust Atlanta into the mainstream of America’s political economy. It was upon the base largely built by him that Jimmy Carter rose to national power. It was no accident that J. Paul Austin legitimized Carter for the Northern banking centers, or that candidate Carter used Coke’s international sales network, instead of the State Department, for his foreign trips, or that his closest advisor Charles Kirbo, and the head of the transition team, Jack Watson, and his new Attorney General, Griffin Bell, all came from King & Spalding, the law firm that has long knit its two chief clients, Trust Company of Ga. and Coca-Cola, into the dominate force in Atlanta. Changing what comes out of the White House vending machines from Pepsi to Coca-Cola is only one of the smaller ways President Carter will return the favors. But that’s another story. * Recent figures indicate that half of the 600 Coca-Cola bottlers are still controlled by only 57family dynasties (mostly Southerners). In 1971, the Federal Trade Commission issued a formal complaint against soft drink franchise systems, charging that the provision giving bottlers a territorial monopoly restricted competition and cost consumers an extra $1.5 billion per year. Coke bottlers led what then Senator Fred Harris called “the biggest lobbying effort I ever witnessed” to block the FTC with special interest legislation, and when the company president came to testify before Congress, he brought along Joseph Califano, then a skilled lobbyist frequently employed by Coca-Cola, now Jimmy Carter’s Secretary of HEW. Observers now predict that the FTC staff will lose its battle to have bottlers compete with each other across territorial lines. * With the rise of consumerism in the 1960s, the Food and Drug Administration revived its opposition to Coke feeding kids caffeine without their mothers’ knowledge. Through its adroit lobbying, Coca-Cola held out until the FDA chief could be replaced with a friend of the industry, then got what’s known as “the Coca-Cola Amendment” passed which made caffeine a mandatory ingredient for all “cola” and “pepper-type” drinks - its answer to the question, “How do we know what our kids are drinking?" The amendment left the labeling of ingredients optional, so when Coke began listing caffeine as an ingredient on the drink’s bottling caps, it proudly claimed that it “voluntarily initiated a program of ingredient labeling … that went beyond what was required . . . [and set] an example for the rest of the soft drink industry.”

Sidebar

CASE STUDY IN FLORIDA: MIGRANTS, MONDALE, CALIFANO AND COKE

What happens when the nation’s most successful boycott organizers take on the makers of the world’s best known product? Twice in the last five years, Caesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers have threatened a full-scale boycott of Coca-Cola if the company did not order its Minute Maid subsidiary to sign a union contract with Florida grove workers. Both times, the UFW won.

“We knew the thing they hate worse than anything is bad publicity,” said Mack Lyons, chief organizer for the UFW in Florida. “We threatened to bring attention to how they were dealing with their workers, and to boycott them if necessary. We knew that despite all their publicity about world harmony, they didn’t give anything unless they were pushed hard. We played to their weakness, and that’s their ‘good-guy’ image.”

The UFW won the original contract with relative ease in January, 1972, when it caught Coca-Cola reeling from the embarrassment of an NBC documentary on the inhuman treatment of migrants by citrus growers. Coca-Cola had bought Minute Maid in 1960, the same year Edward R. Murrow’s devastating “Harvest of Shame” brought a flurry of national attention to Florida’s migrants. Ten years later, the NBC Special revealed the same conditions: crowded camps, two and three families living together in tar-papered shacks without indoor plumbing, crew leaders who cheated “their” workers, arbitrary pay scales, nonexistent safety and sanitary provisions in the fields.

With 30,000 acres of Florida groves, Minute Maid is the country’s largest citrus processor, and appeared in the film to be the biggest exploiter of migrant fruit pickers. “We decided that was not the kind of image Coca- Cola wanted to be associated with,” explained William Kelly, vice-president for Coke’s grove operations. To repair the damage, the company launched a massive effort, the real purpose of which, said Lyons, was “to clean up their image.” Company chairman J. Paul Austin used his appearance before Senator Walter Mondale’s Subcommittee to proclaim Coke’s disapproval of the “deplorable” conditions in Florida and offered his help in creating a National Alliance of Agribusiness to aid minorities in agriculture. Austin was accompanied at the hearing by Coke’s Washington attorney and skillful lobbyist, Joseph Califano, who had done the necessary preliminary work to prime the Congressmen and press for Austin’s “self-effacing candor.” It mattered little that the Alliance Austin suggested never materialized; his promises won immediate praise from Senator Mondale and a blitz of priceless publicity about Coke’s concern for farmworkers.

To shore up its image further, the company poured millions of dollars into a highly publicized Agricultural Labor Program to improve living and working conditions. It also signed the first labor contract covering farmworkers in Florida history. Aware that Coke could not resist organizers in its groves without suffering public ridicule, Caesar Chavez had sent his cousin Manuel into the state to sign up Coke’s workers. Within six weeks, 76 percent had signed cards indicating they wanted to be represented by the UFW. Negotiations with the company began in earnest, spurred by a few strategic visits to Coca-Cola bottlers by UFW boycott sympathizers. By early 1972, the union got what Chavez called “the best contract farmworkers have gotten anywhere the first time around.” And instead of a boycott, the company reaped glowing press coverage of its humane treatment of farm laborers, and a fistful of awards for “good citizenship.” (As it turned out, sometimes the award-givers needed a little push. The committee of the Anti- Defamation League which honored Austin for his “humanitarianism” was actually headed by a top executive of McCann-Erikson, the advertising agency for Coca-Cola.)

With its image restored and the UFW clearly preoccupied with commitments in California, Coke felt little pressure to renew the union contract when it ran out in January, 1975. Under its Agricultural Labor Program, Coke simply phased out its use of migrant labor so it couldn’t be embarrassed again. Now its labor relations problems were more typical of giant corporations that squeeze their workers whenever possible. “When the contract expired, they just waited to see what we could do,” said Lyons. “They knew we couldn’t strike in this economy, and they felt very secure with their new image.”

“As soon as the contract went down, things got very tough,” said Watson Carter, a veteran Minute Maid fruit picker who made $9,000 in the last year covered by the UFW contract. “They’d take us in a grove and tell us the rate we’d get, and if we didn’t like it, they said they’d find others to pick it. It’s like holding a gun to your head.” Under the old contract, a committee of UFW and Coke representatives set piece rates above the standard 47^-per-box figure for groves with poor trees and high grass. “They ended all that,” said Carter. “It was take it or leave it — just like the old days before the union. Of course, they still paid us a little more than others so they could brag about being the best in the industry — but we knew they could do more.”

William Kelly claims the company voluntarily extended the expired contract “in all its terms” on a day-to-day basis, and continued the “hardship” rates for bad groves. But an examination of Carter’s pay-stubs confirms his average price rate and total income dropped 20 percent from the previous season.

“That’s just the way they do it,” says the soft-spoken Lyons. “They tell the press one thing and tell us something else. If we could just get them to do what they say they do, we figured we’d be in fine shape.”

Negotiations for a new contract continued through the winter and spring of 1975 with little result. By the summer, the farmworkers were getting restless. On July 4, they read a Declaration of Independence from Coke’s “paternalism” in front of the Minute Maid headquarters in Auburndale, and Lyons began a 16-day publicity-seeking fast. Charges and countercharges began to fly, but little word of the conflict spread beyond the state. Then in August, after the California legislature passed its Agricultural Labor Relations Act for supervised elections between the Teamsters and UFW, the union staged small demonstrations at Coke’s Atlanta and Houston offices to let the company know well-oiled boycott machinery was free to tackle a non-California target. At the national UFW convention in September, the members endorsed an international boycott of Coca-Cola “if it becomes necessary.”

“Things went much better in negotiations after that,” declared Lyons. “Everything was on the table. Coca- Cola’s Kelly agreed that “we were very close,” but when several more meetings produced no results, Lyons and a group of farmworkers drove to Atlanta to begin a three-week series of around-the-clock sit-ins inside Coke’s office building, culminating in the arrest of four union members for criminal trespassing. As the union hoped, the demonstrations brought in the national media and Coca-Cola capitulated. It sent a delegation of senior officers to La Paz, California, to meet with Chavez himself and sign a new three-year contract.

“They were playing a public relations game with us all along,” concludes Lyons. “The Atlanta actions put us over the top because they let the company see what a boycott campaign could do to their image.” Company spokesmen refused to comment on the union’s tactics.

Coca-Cola’s image is perhaps the best monitored and most carefully cultivated complex of symbols in the world — the Pope and the Presidency notwithstanding. Today, a $200 million advertising budget and a sophisticated legal and public relations team insure that nothing controversial (like pollution or discrimination or migrant labor) becomes identified with the products.

“You’d be sensitive about your image, too, if everybody knew your name,” explained a finance officer. “Can I quote you on that?” a reporter asked.

“Absolutely not,” he shot back. “The company has a very strict policy that all answers for the press must come from the public relations department. If you quote me in an article, I’ll be fired. It’s as simple as that.”

Despite such enforced carefulness, the embarrassing truth about what really goes on behind “The Real Thing” occasionally hits the headlines. When it does, the Coca-Cola team is mobilized to quell, if not co-opt, the source of opposition. For example, there was a tremendous uproar in 1966 when the Jewish community in New York City discovered that Coke had refused to award a franchise to an Israeli bottling firm because it feared losing its multimillion dollar business in the Arab countries - many of which had a higher per capita consumption of Coca-Cola than the US. In the course of a week, the Anti-Defamation League denounced Coke, the New York Times exposed it, and businesses from Mt. Sinai Hospital to Nathan’s Famous Hotdog Emporium threatened a boycott. Coke’s management was “deeply distressed over the high emotional content” of the charges, which they claimed were “unfair and unfounded.” Their first line of defense was to say that no “suitable” bottlers could be found in Israel, but by week’s end, with the controversy still raging, they miraculously found a franchiser for Israel. In retaliation, the Arabs mounted a total boycott of Coca-Cola. From the company’s perspective, it was a price worth paying in order to prevent a greater loss of reputation in America.

Florida’s farmworkers may prove to be a much more difficult constituency to co-opt. And the truth about Coke’s “model” programs for its workers may prove a recurring burden for the purveyor of world harmony — especially as long as the UFW is there to make waves — because the real story of what has happened at Minute Maid differs substantially from the glossy hand-outs distributed by Coca-Cola.

Coke began tampering with its Florida image even before it became national news in 1970. Just before NBC aired its “White Paper” on migrants, Coca-Cola President J. Lucian Smith (then president of the company’s Foods Division) engineered a meeting with NBC producer Reuven Frank which resulted in the deletion of the two segments most critical of Coke. After the broadcast, copies reproduced for distribution to libraries and schools had a special notice attached at the end of the film telling viewers that Coca-Cola had since undertaken a comprehensive program to upgrade the living standard of its workers.

The company steadfastly maintains that its Agricultural Labor Program (ALP) began well before the bad publicity. J. Lucian Smith, it says, toured the Minute Maid operations in 1968 and returned to Atlanta to report conditions so bad they “could not in good conscience be tolerated by the Coca-Cola Company.” In fact, nothing concrete was done until the NBC documentary and Senator Mondale’s Subcommittee on Migratory Labor brought Coke’s policies into the national limelight. Even then, Coke’s efforts seemed designed for their publicity value. Each new step in the ALP was announced with handsome PR materials, glossy photos, and special press tours. A journalist was hired to see if a book might be written on the project’s progress. “They obviously viewed it as a long-term goodwill investment,” the reporter recalls. But the book was soon deemed “too heavy-handed” and abandoned in favor of a 25-minute color film which the company still shows visitors. Smith sent personal letters to friendly newspapers indicating that their “editorial support means much to us.” The subsequent orgy of “promo” materials prompted Otis Wragg, then editor of the New York Times-owned Lakeland Ledger, to protest: “When I see them spending about as much for publicity as they do for actual services, then I have to question their effort.”

Despite this history, William Kelly, the man in charge of the ALP, still tells reporters, “One of our principles was that anything in connection with the project would be open, but we would not seek publicity ourselves. We didn’t want it to be a public relations tool of the company. . . .We have not attempted to generate publicity about it ourselves.”

Reality again diverges from Coke’s misleading, if not deceptive, descriptions of the Agricultural Labor Project’s three principal program areas: housing, social services and health care, and employment. Company propaganda suggests the programs were designed to “break the endless cycle of poverty” affecting farmworkers. In fact, the thrust of each program has more to do with creating a more stable and productive workforce for Coca-Cola with government subsidies and a minimum of public criticism.

Housing: Perhaps the most publicized part of the Agricultural Labor Project is the 85-home Lakeview Park development that Coca-Cola “made happen,” as Kelly puts it. Company brochures and magazine articles in publications like Reader’s Digest and the Atlanta Constitution describe the development, located in Frostproof, Florida, as a pristine delight, complete with a lakefront pavilion and community-owned orange grove. But for most Minute Maid workers the project has been quite upsetting. To begin with, Coke tore down the camps that had housed some 600 workers in the peak season. Those who couldn’t get into the relatively tiny, 85-home Lakeview Park had to move on or find quarters elsewhere. For those who could get in, the $14,500-to-$ 18,000 cost of the homes meant that monthly mortgage payments, even with FHA financing, began consuming an exorbitant portion of their payroll checks.

“There’s a lot I don’t like about this setup,” says Larry Hill, a picker for Minute Maid. “The finance company has been raising my payments since I got here. It started out at $80 a month; now it’s $151. We had a bad year here, so that makes it hard.” The pressure of constant payments forced workers to be more efficient pickers; if they couldn’t make it, the company hoped others would move in who could handle the responsibility of home' ownership — namely the more stable worker who had probably never been a migrant. Sometimes those who managed to get into Lakeview Park were forced to leave through no fault of their own. Aaron Banks was one of the first to move into the new homes, but when he fell from one of Coke’s citrus trees, and injured his back, he lost his income and eventually defaulted on his house. Ironically, he was forced to move in with friends in one of Coca-Cola’s old migrant camps, which now belongs to a local church. The case of Banks’ foreclosure is far from unique. Spokesmen for the ALP continue to describe the project as “a success story,” but today more than one-fourth of the 85 homes are empty. Because all but three of the homes have been sold at least once, Coke has gotten back nearly all its original investment in starting the development. “Our number one objective was that the company should not make any profit on Lakeview Park,” Kelly volunteered. “The number two objective was to lose as little as possible.”

Health and Social Services: Frostproof is also the site of Coke’s model health clinic. Far from being “unprecedented,” the clinic is one of 14 similar units across the state under various sponsorships. It’s not the biggest, nor does it focus on servicing migrants. In fact, in comparison with the other clinics, Coke’s Frostproof project looks more like a sophisticated company program for keeping workers healthy than the “unique self-help” program described in public relations brochures.

The West Orange Farm Workers Clinic (WOFWC) in nearby Apoka provides an illuminating contrast to Coke’s operation. A genuine, community-based project, without the financial assistance of Coca-Cola, WOFWC has had to hustle for everything it’s gotten. Even though the clinic serves many Minute Maid grove workers, the company rejected a plea for a piece of its land that the clinic originally selected as an ideal site.

“Coke had a chance to help us and they didn’t,” says Ellery Grey, WOFWC’s director. “But we got by anyway. It made us do our own work, and we’re better off for that in the end.” Grey would still like to get a chunk of Coca-Cola’s money, but he doesn’t want to be considered a part of their operation. “Two months after we opened we were serving more people than Coke’s Frostproof clinic. We provided more programs with a smaller budget. I’m not criticizing their efforts; their dentistry program is especially strong. But maybe the image they promote is more than what they’ve earned.”

Along with the Frostproof clinic, Coca-Cola has created four area Community Development Corporations which sponsor tutoring, libraries, child care, recreation, and related programs such as a comprehensive screening program of the health needs of its employees. The company has spent about $7 million for all these programs; since 1970, however, Kelly admits that over $1 million of this money went straight to outside consultants who helped launch the CDCs. About 20 percent of the funds for the CDCs comes from HEW — now headed by Coke friend Joseph Califano. Meanwhile, the Woodruff Foundation, which is controlled by the 87-year-old powerhouse behind Coke, Robert W. Woodruff, and which ranks among the top seven foundations in the country (assets: $250 million + ), gives away several million dollars each year to medical programs, primarily Emory University’s Woodruff Medical School. Why doesn’t the Woodruff Foundation help out in Florida? “We were encouraged not to ask them,” an ALP staffer replies awkwardly. “They have other concerns.”

Employment: Ironically, Robert Woodruffs old maxim, “I want everybody associated with Coca-Cola to make money,” is occasionally mentioned in connection with what the company calls “the one major goal” of the Agricultural Labor Program: “to break the endless cycle of poverty that is often the lot of the migratory worker and to give to that worker a sense of stability and opportunity to enjoy the benefits made possible in today’s economic system.”

To implement that goal, Minute Maid reorganized its labor force of 1500 into 250 hourly-paid grove workers and 950 piece-rate harvesters. The problem of the 300 migrants the company normally hired was solved by simply doing away with their jobs, and increasing the work load for the remaining employees. Within a year and a half, productivity had increased 20 percent; in three years, the turnover rate had dropped by half. Today, hiring is done through the union hall, and according to Kelly, the crews are composed of “basically the same people” from year to year. Unlike most citrus companies, Coca-Cola profits by hiring pickers year-round because it can use them to harvest its huge lemon groves in the off-season for oranges.

Those who have remained on the stabilized payroll receive the best wages in the industry and a package of vacation, sick-leave and pension benefits that is, as the company says, “unparalleled” for citrus workers. But to call the benefits “generous” — another Coke catch-word — is stretching credulity. In the first five years of giving better benefits, the program for 1200 employees cost Coke about $2 million. Minute Maid spent that much in a few weeks not too long ago to advertise a new brand of orange juice which it later recalled from the market.

According to Mack Lyons, the increased wages and benefits were the only good parts of the ALP — and the union deserves the credit for making them permanent. “The problem is not housing or social services, but economics,” says Lyons. “Coke wants to sell the problem their way so they can get the government to subsidize what should be their responsibility. If they provided decent wages, they wouldn’t need those programs. That’s why people want us here. They know they can’t trust Coke.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.