Klan Confrontations: Offensive, Defensive Tactics

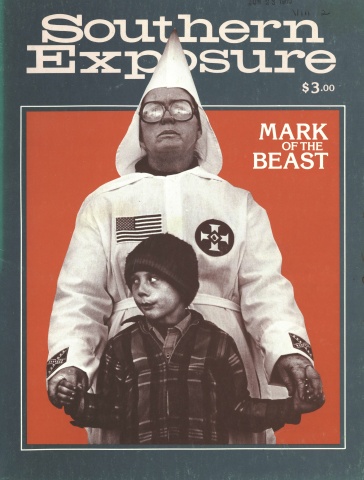

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

On November 3, 1979 — the same day five Communist Workers Party members were shot down by Klansmen and Nazis during an anti-Klan rally in Greensboro, North Carolina — Klansmen were literally being run out of town by protestors in Dallas, Texas.

About 40 Klansmen participating in the “March of the Christian Soldiers” would have actually been marching off to war if police had not whisked them away from the jeering, hostile crowd of 3,500 people chasing them.

After herding the Klansmen into the courthouse’s heavily guarded basement to disrobe, police put them on a chartered bus that took them outside the city limits and then escorted them home in police cars.

“The crowd just got bigger and bigger and more violent,” said Lieutenant Charles T. Burnley, who directed the Dallas police’s 100-member tactical unit that day. “And we did have on all our riot gear, you can believe that. I think if we had stayed on the street for another 30 minutes, we would have had a big street brawl.”

The Dallas incident is only one recent example of Southern communities reacting aggressively to the Klan. The “ignore them and they’ll go away” attitude is increasingly being rejected. And in some communities — China Grove, North Carolina, and New Orleans, for instance — the emerging attitude is “Get them before they get you.”

“Not only are blacks no longer afraid of the Klan,” says Ozell Sutton, Atlanta Regional Director of the U.S. Justice Department’s Community Relations Service, “but they are antagonistic against the Klan. And now we have situations of blacks heckling Klansmen like Klansmen used to heckle blacks.”

Sutton cited the Greensboro killings as an example of what heckling could cause. “I don’t know where the end is,” he said. “In the foreseeable future and as the economy gets worse, I see an increased antagonism between the Klan and black demonstrators. It just makes you quiver.”

Unlike the situation in Dallas, where people reacted to Klansmen coming into their community, the Greensboro killings were the result of Communist Workers Party taunts that dared the Klan to come and get them. The Greensboro November 3 rally was publicized as a “Death to the Klan” rally, and the CWP had held a press conference two weeks before in Kannapolis, North Carolina, a Klan stronghold. There, CWP member Paul Bermanzohn, later wounded in the shooting, challenged the “Ku Klux Klan cowards and two-bit punks to come out and face the wrath of the people.”

Greensboro residents, particularly those who lived in the low-income housing project where the shooting occurred, felt that their turf had been desecrated for a cause that was not their own. The rally had been scheduled for another site, but was changed to the Morningside Housing Project at the last minute for security reasons. Many residents said the CWP protestors shouted insults at carloads of whites driving slowly through the community, minutes before the shooting.

“I think if the Communists had not done all of that instigating like they did, it would never have happened,” said Charlotte Ramseur, who rushed her two children into the house when the shots rang out.

CWP members reject that reasoning, calling it “bourgeoisie propaganda.” Nelson Johnson, a Greensboro CWP organizer, said the group’s verbal attacks on the Klan were merely political statements; accepting the idea that the Communists provoked the incident, he said, “lets the Klan off the hook and turns it into a CWP issue. But it’s a Klan issue.”

There had been efforts to keep the Klan from marching in Dallas. On October 26, the Dallas City Council had approved a resolution urging the Klan not to march and ordering city staff to find some way to cancel the Klan parade permit. But Dallas Police Chief Glenn King contended he could find no legal grounds for canceling the permit.

Gerald Weatherly, a Dallas civil rights attorney for more than 20 years, filed an unsuccessful suit in federal court charging that Chief King violated federal and state law by allowing the march. Weatherly’s claim was that the Klan should not be allowed first amendment rights because it works in disguises against federal laws on desegregation.

The leader of the Dallas Klan mobilization was Addie Barlow Frazier, a 73-year-old grandmother known to most as “Dixie Leber” (that’s “rebel” spelled backwards). To anti-Klanners, she is simply “Granny Hate.”

At the hearing on Weatherly’s charge, Mrs. Frazier said the march was to “save an endangered species — the white race.” The hearing went much like a comedy routine. Mrs. Frazier held her nose and frowned as Weatherly approached her for questioning. At another point, she kicked aside and refused to sit in a chair he had sat in, declaring, “It needs to be fumigated.”

At least two factions of Klansmen participated in the march — the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan led by James Venable of Stone Mountain, Georgia, and the National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan led by David Duke of Metairie, Louisiana. Three anti-Klan protestors were arrested for disorderly conduct and one for trying to use a policeman’s nightstick on a Klansman’s head.

Despite the crowd’s vehement reaction to the Klan’s march in Dallas, a broad-based group called the Coalition for Human Decency was able to pull off a nonviolent anti-Klan rally as a response to the Klan march. But they faced opposition from local government leaders.

“From the beginning, we had trouble with city government and the status quo,” said Kwesi Williams, a Coalition leader and a former organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “They were saying, ‘If you leave them alone and don’t draw any publicity, they will go away.’ But we knew some kind of strong, mass response had to be done. At first, we had to decide to put aside our differences and petty squabbles. We crossed a whole lot of traditional political lines that were typically taboo and came up with a grassroots movement.”

The Coalition’s approach was to adopt an attitude that could be termed “anti” but not hostile or violent. “We didn’t come out just against the Klan,” said Williams. “We agreed it wasn’t just a white-black issue. We were able to pull together a very broad base of people - blacks, whites, Mexicans, rich, poor. The nuns were there in their habits and everyday people in their jeans. And they were all talking about the Klan.”

Organization was the watch word for anti-Klan protestors in China Grove, North Carolina, a town of 2,100 about 30 miles north of Charlotte. But protests there hovered dangerously on the brink of violence.

On July 8, 1979, about 100 demonstrators — armed with shotguns, pistols and billy clubs — surrounded the China Grove Community Center where Klansmen were showing The Birth of a Nation, the 1915 film glorifying the Klan. The group of protestors, which included members of the Communist Workers Party, burned two of the Klan’s Confederate flags and beat two of the center’s pillars with tire irons while Klansmen waved guns and exchanged insults with them. China Grove police pushed the Klansmen inside the center. Gorrell Pierce, grand dragon of the North Carolina Federated Knights of the Ku Klux Klan — carrying a .45 caliber automatic pistol in his belt — insists, “We were a millimeter away from violence.”

Despite the protestors’ aggressiveness, they had not planned any physical confrontation with the Klan, says Nelson Johnson, a CWP organizer who escaped with wounds from the Greensboro massacre four months later. “The plan,” Johnson says, “was to establish publicly that these racist views should be denounced forthrightly and in the presence of those propagating it.”

Believing that Klansmen were following them after the incident, protestors stationed a round-the-clock guard around the town’s black community. More than 75 armed and helmeted guards, working four-hour shifts, watched the narrow entrance to the black community for more than a week. All media and strangers were thrown out of the area; even earnest inquiries and statements of support were met with silence or ridicule.

Community organizers of the security still refuse to discuss their efforts. Some point out they have reason to be on guard — their sheriff, Rowan County Sheriff Robert Stirewalt, campaigned as a Klansman when he was elected to office in 1966.

“I think the organization of the community patrol served as a deterrent to crime,” says Johnson. “And it made a very good political statement — a group such as the Klan should not be granted permission to spread or act on its racist views. The spirit of the people to fight this and protect themselves was absolutely necessary.”

But now, since his experiences during the Greensboro slayings, Johnson feels that confrontation with the Klan actually works against the anti-Klan movement by distorting a view of the true enemy — capitalism.

“The economy is falling apart,” he says. “People have to be convinced that other people are causing their problems. It’s a scapegoat mentality that escalates a broad-based conflict between different ethnic groups. That’s the political danger of confrontation.”

In New Orleans, however, some anti-Klan protestors have accepted confrontation as the only viable strategy in dealing with the Klan.

On November 26, 1978, about 100 of David Duke’s Knights of the Ku Klux Klan marched from the French Quarter to Liberty Monument, site of a Reconstruction-era battle between white supremacists and police. The monument commemorates a September 14, 1874, battle in which the White League took over the state house. It was surrendered a week later when President Grant moved in with the Navy and more federal troops. But the monument continues to stand as a tribute to white supremacy — despite the words “Black Power” spray-painted across it, and a plaque the city added in 1974 saying that the inscriptions “are contrary to the philosophy and beliefs of present-day New Orleans.”

The Klan could hardly have picked a more explosive moment for their march. The city was packed with 75,000 blacks fans attending the football game between Grambling State University and Southern University, and with a big crowd celebrating a festival of black food and culture.

Mayor Ernest Morial, the city’s first black mayor, tried in vain to dissuade blacks who said they would hold an “educational rally” at the statue and await the Klan. “The mayor and everybody else came out and said that both groups marching to this little plot of land would cause confrontation,” says Jim Hayes, an organizer of the anti- Klan protest. “We knew that from day one. It was elementary that little plot of land could not be shared by two groups. We wanted a confrontation. You can’t deal with the Klan passively. They are men who will turn to violence and destroy a man anytime.” Hayes, vice-president of the National Tenant’s Organization, pulled eight low-income community organizations into the Black Committee for Action. Feeling certain that the city would try to stop their march, the group didn’t even apply for a parade permit.

“It wasn’t no parade,” says Hayes, chuckling over the way the group sidestepped the legal hurdles. “We just all decided we were going to meet at a certain place at a certain time and just started walking. Just 500 individuals all walking in the same direction. That’s all.”

But when the protestors approached the statue, police were already escorting the Klansmen away, having persuaded them to rally two hours earlier than publicized. A few catcalls and punches were exchanged, but a showdown was averted, and the Klan’s attempt to gain public attention as a potent organization failed.

Hayes is convinced his direct-action approach works and is accepted by the majority of black people. And he may be right. Effective direct-action strategies, like those used throughout the history of resistance to white vigilante terror, include considerable community education before a mass-based “collision” (see box) works as a defensive tactic. Anti-Klan groups in Dallas and New Orleans succeeded by focusing day-to-day organizing on the threat of the Klan and the need for united action. Their tactics stand in marked contrast to the rhetorical calls issued in Greensboro for the Klan to “face the wrath of the people.”

“I hope the Klan comes back to New Orleans,” says Hayes. “I think we would like to set an example of how we should deal with them.”

1867: Midnight Collisions

Bat. Maj. Genl. John Pope Calhoun, Georgia

Commanding 3rd Military District August 25th 1867

Georgia, Alabama and Florida

We the Colored people of the Town of Calhoun and County of Gordon, desire to call your attention to the State of Affairs that now exist in our midst.

On the 16th day of this month, the “Union Republican Party’’ held a Meeting in this Town, at which the Colored people of the County attended “En Masse”, and since that time we seem to have the particular hatred, and spite, of that class who were opposed to the principles set forth in this Meeting.

Their first act was to deprive us of the privilege to worship any longer in their Church. Since we have procured one of our own, they threaten us if we hold meetings in it.

There have been houses broken open, windows broken, and doors broken down in the dead hours of the night, men rushing in, cursing and swearing and discharging their pistols inside the house. Several times came very near shooting the occupants. Men have been knocked down, and unmercifully beaten, and yet the authorities do not notice it at all. We would open a school here, but are almost afraid to do so, not knowing that we have any protection for life, or limb. We would humbly make this our petition to you, that something be done to secure to us the protection, we so much desire.

We do not wish to complain, but we feel that our lives are no longer safe. Therefore, we feel competed to ask your protection. We wish to do right, obey the Laws, and live in peace and quietude, and will do so if we are permitted to, but when we are assailed at the Midnight hour, our lives are threatened, and the Laws fail to protect, or assist us, we can but defend ourselves, let the consequences be what they may. Yet we wish to avoid all such collisions, and if possible will do so until we hear from you.

We would respectfully ask that a few Soldiers be sent here, believing it is the only way we can live in peace, the only protection we can have, until after the Elections this fall.

Hoping you will take such action in the premises, that will conduce to the best welfare of the people, as well as to secure peace and protection to ourselves, we most respectfully submit the foregoing to your consideration.

— Signed by 24 black citizens, each affixing his mark.

Document from the Freedmen & Southern Society Collection, University of Maryland

Tags

Vanessa Gallman

Vanessa Gallman is a black writer who covers government for the Charlotte Observer and who covers Klan activity throughout the South. (1980)