This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 1, "America's Best Music and More..." Find more from that issue here.

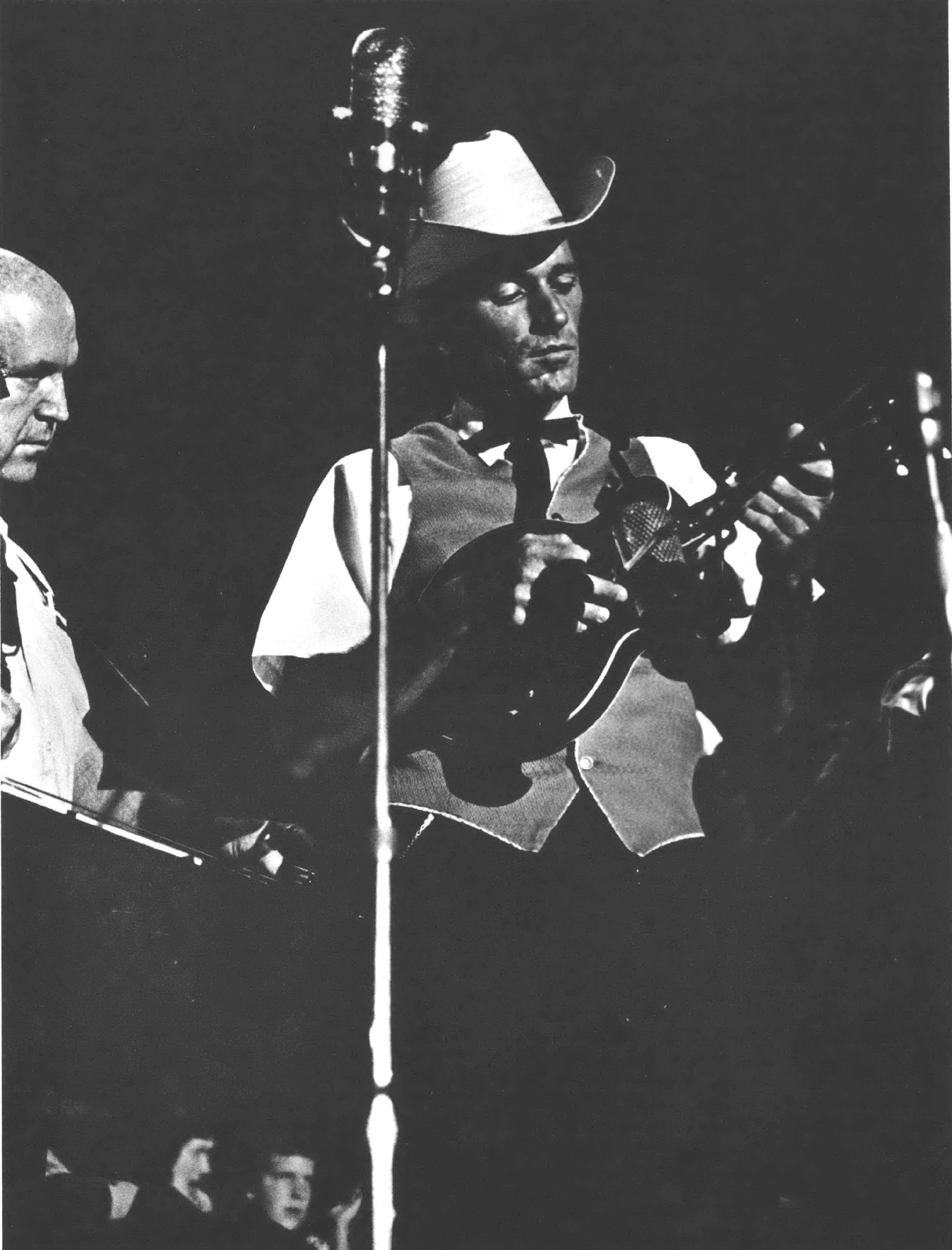

The dark ominous clouds burst into a driving thunderstorm. Long lines of people waiting for festival tickets covered themselves as best they could. Waiting for my friends, I found a niche under an old protruding stone ledge and watched the heterogeneous audience of mountaineers and tourists interact under the adversity of the elements. Within this fascinating collage of musicians and audience arriving in the pouring rain, a single car pulled into the no-parking zone in front of the Asheville, North Carolina, civic auditorium and stopped. I watched several people climb out behind their umbrellas. Then a tiny, frail man appeared in an impeccable white suit. Leaning on the arms of two of his brood, Bascom Lamar Lunsford had come to direct the Saturday night finale of the Forty-Sixth Annual Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, held in Asheville on August 4, 1973.

If this had been the first festival in 1928, when Lunsford brought his friends together at Pack Square, the instruments would have been drenched as well as the people, but the dancing would have gone on. From the first small gathering, an appendage of Asheville’s Rhododendron Festival, Lunsford had taken his festival from Pack Square to the local ball park and finally to the civic auditorium. In the process, he gained world wide acclaim as a collector and preserver of pure mountain music, serving as U.S. representative to the first International Folk Festival in Venice. But the Asheville Mountain Music Festival remained Lunsford’s greatest joy, as it did for thousands of his friends and guests.

He looked his ninety-one years as he painfully climbed from the car and negotiated the growing rain puddles. His eyes reflected some fright and confusion as scores of people approached his entourage. Lunsford must have sensed that this would be his last time to call out the numbers, signal for the doggers, and listen to pure mountain tunes from the fiddles and banjos of friends from Sandy Mush and Ivey Creek, from Weaverville and Swannanoa. One month later, on September 4, 1973, the “Minstrel of the Appalachians’’ died. The 46th Annual Festival was the last in Asheville’s old civic auditorium. A major face-lifting of the auditorium beckoned the Festival to yet another home. The rhythms of the music, the tireless right hand of the banjo picker, and the intricate movements of the doggers sounded the end of an era.

The Minstrel’s Mission

Bascom Lamar Lunsford lived a long and full life. He dabbled and searched for answers, as a school teacher, a lawyer, and a politician, but his real commitment was to mountain people and mountain music. Long before Appalachian studies or Foxfire or schools of folklore, Lunsford understood the importance of his history and the heritage of his mountain kinsmen and neighbors. As he said near the end of his life:

the key to whatever success I’ve had . . . has been in realizing the value of the fine tradition in mountain people. I’ve spent the night in more cabins between Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and Iron Mountain, Alabama, than anybody— and I know!1

A special part of mountain culture for Lunsford was the traditional music that had been handed down through the generations from the earliest Scotch, Irish, British, and German settlers. He had been playing the fiddle and singing traditional tunes since he was eight. Neither an academically trained folklorist, nor a polished recording star, Lunsford simply shared what he knew and did what he loved. He gathered songs, traveled deep into coves to record lost tunes, lectured, recorded, organized festivals, and encouraged fledgling fiddlers.

Lunsford worked at preserving the mountain music in such a variety of ways that he became known as the “Minstrel of the Appalachians.” He catalogued tunes and sought out the sources of the music, but he did more than just collect, analyze, and reflect. The music was not to be appreciated merely as a relic of the past but sung, danced, and played as a part of a vibrant living culture. John Parris, the western North Carolina folklorist and a friend of Lunsford’s since 1927, recently recalled that “Lunsford kept these people interested in keeping bows rosined and their banjos tuned.”2

Lunsford’s primary vehicle for keeping the music alive in his native mountains was the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. Despite the growing influence of radio and commercial music, his Festival transcended first the rise of honky-tonk country music and the power of Nashville’s WSM and then the commercialized bluegrass circuit and the power of slick advertising. Neither country and western nor bluegrass, the format and the music remained consistent through the years. Pure mountain music, rooted in the Scotch-Irish ballads and passed down through an oral tradition, was played by local musicians on the traditional instruments—banjo, fiddle, and dulcimer. Guitars, bass fiddles, and mandolins have been added through the years, but electric instruments were unwelcome and modern songs seemed strangely out of place. Even on Lunsford’s final night at the Festival, his influence remained strong as a feeble version of “Dueling Banjos” drew polite applause while the audience greeted “Old Grey Eagle,” a traditional tune, with rousing enthusiasm.

Lunsford’s work as a folklorist spanned a fifty-year period of complex social change in the Southern Appalachian Highlands. Outsiders were coming into the North Carolina mountains. The National Forest Service, the National Parks, and T.V.A. gained control of huge areas of land; large industries such as Champion Paper Company in Canton (fifteen miles west of Asheville) and the proliferation of small textile mills throughout the Asheville area added the industrial class distinctions of management and labor to the culture. Tourists came to view the gorgeous mountains, spawning an economic dependence on this seasonal trade, and in their wake came corporate developers with ski resorts and golf courses, condominiums and vacation homes. The tiniest mountain coves were invaded by television, antipoverty workers, and Appalachian Regional Commission bureaucrats. Roads, television, industry, and the tourist trade pushed mountain people into the American mainstream and in the process threatened mountain culture with extinction.

Lunsford was aware of some of these dangers, and revealed his perception of them to John Parris:

It was a time . . . when paved roads, electricity, and outlanders seeking sites for industrial plants were beginning to bring about great changes in the traditional life of the mountains. [As the mountain people adjusted to new ways,] they had even begun to hold the fiddle and the banjo in low esteem as crude, old-fashioned instruments. And the music which their ancestors had played and sung they thought of as a relic of the past. Only the old ones held on to their heritage with any degree of steadiness. The younger generation was growing away from the old music. It was far from dead, but it was slowing dying.3

He responded to the menace of assimilation with what he knew, the music and its impact on mountain people. His fame and legend indicates his success in preserving the traditional mountain music. His value as a “folk hero” was clear in his final Festival as person after person came to the stage to play the traditional tunes. But the threats to mountain society continue to grow stronger and more complex, revealing the limits of Lunsford’s approach to cultural survival. To understand these limits, his life must be viewed in the context of the changing political realities in the Appalachian region and especially in western North Carolina.

Growing Up in Changing Times

Lunsford was born in Madison County, North Carolina, one of the most rugged counties in the state. Bordering on Tennessee to the north, Asheville’s Buncombe County to the south, and mountainous Yancey and Haywood Counties to the east and west, Madison descends from the 5000- foot elevation of the Bald Mountains to the bottom land where the French Broad River enters

the county at the Tennessee border. The county’s population has always been small and homogeneous. The census figures reveal two important aspects of its development: the periods of growth and decline, and the racial makeup:

1860 5,908 213 Negro slaves, 17 free Negroes

1890 17,805 710 Negroes

1900 20,644 558 Negroes

1940 22,523 106 Negroes

1960 17,217 110 non-whites

1970 16,003 100 non-whites

Before the Civil War scarcely anyone except the Baptist missionaries and the famous Methodist circuit rider, Francis Asbury, took notice of this tiny population. The isolation of Madison and the paucity of slaves made the county a Union stronghold where Colonel George Washington Kirk led the Second and Third North Carolina Mounted Volunteers of the Union Army. Two factors are responsible for the extraordinary growth from 1860 to 1890: the completion of the Western North Carolina Railroad from Tennessee to Asheville in 1882 and the founding of Mars Hill College, a Baptist-supported school, in 1859. Although warm springs were discovered near the Tennessee border in 1799 and a small hotel had been built, the tourist business grew in Hot Springs only after the completion of the railroad facilitated travel. While Hot Springs attracted regional tourists and some world travelers, Mars Hill nurtured a small pocket of indigenous middle-class educators.

James Bassett Lunsford, an ex-Rebel soldier, a school teacher, and a good judge of a fiddler, came from Texas to a teaching job at Mars Hill College in 1866. In 1870, he married Luarta Leah Buckner, who was a granddaughter of one of the original trustees at Mars Hill College and who knew scores of old mountain songs herself. Bascom Lamar was born on March 21, 1882, in Mars Hill.

Exposed to the diversity of this mountain culture, Bascom and his brother started playing homemade cigar-box fiddles at an early age. They learned mountain tunes at apple peelings, tobacco curings, and house raisings. But Bascom’s daddy was not a farmer; he was not tied to the land in the same way as a subsistence farmer of the bottom-land or cove depends on the soil and the uncertainty of the elements. Bascom was the child of a school teacher, a professional, and he was pushed to be a good student; as part of an indigenous elite, he was also pushed outside the isolation of such a rural county. Yet as John Parris notes, “he never forgot where he came from .... He never lost his contacts; he grew up with these people.”5

In 1901 the family sent Bascom to Rutherford College, a preparatory school in Burke County on the eastern side of the mountains. Steeped in the times and life of Madison County, Bascom learned new songs at Rutherford from W.B. Love and Fred Moody. He returned to Madison in 1902 to teach in a county school. But in 1903, young and restless, he took a job with the East Tennessee Nursery Company of Clinton, Tennessee. For two years, Bascom traveled on horseback through the mountains peddling fruit trees. But his journeys became a mission for tunes rather than for seeds. He went from Clinch River west of Knoxville, to Big Stone Gap, Virginia, and from Pilot Mountain, N.C., to Brasstown Bald, Georgia.6 As he criss-crossed the mountains, Bascom became a welcome visitor to an isolated family living in a log cabin deep in the mountains. He often traded seedlings for his lodging, a practice not too profitable for the Nursery Company but one that gave Lunsford a chance to visit and find out what old tunes people knew. Banjos and fiddles sometimes appeared, and the family stayed up late into the night sharing songs and making music.

Lunsford was still young and eager for new ventures. After quitting the nursery business, he taught English at Rutherford College for two years and then went into business raising bees. Bascom remembers a particular day, May 28, 1906, when he checked the bees and found the honey as plentiful as he had ever seen it. The story goes that he realized he would have enough money to begin a family, and on June 2, he married Nellie Sarah Triplett, whom he had known since 1887.7 As a husband with family responsibilities that eventually grew to six daughters and one son, Lunsford had to make a living. He continued to teach off and on at Rutherford College, got a law degree from Trinity College (now Duke University), owned and edited a weekly paper for two years, was the solicitor of Burke County Recorder’s Court and an auctioneer, sold war bonds during World War I, and even chased draft dodgers for the Justice Department in New York City.

In the early 1920’s, Lunsford decided to settle down and bought a 140-acre farm on South Turkey Creek outside of Asheville where he built a house with a living room large enough for square dancing. He practiced law and made a modest living. Dabbling in politics as the campaign manager for Zeb Weaver, Democratic candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1922, and as the reading clerk in the North Carolina House, he was a traditional party Democrat with the limited political vision that such an affiliation represented. But just as his numerous earlier jobs had not satisfied him, the practice of law and politics did not capture his spirit either. Throughout the first two decades of the century, he had maintained his avid interest in mountain music but had never turned to music full-time. Cecil Sharp, the famous British collector, came to North Carolina in 1916 looking for traditional songs, especially for the Irish, Scottish, and British influences. Lunsford, then thirty-four years old and lacking confidence with such a renowned musicologist, decided his time had not yet come.8

Becoming a Collector

But Lunsford had grown older. From the stability and economic security of his South Turkey Creek farm, he now had the luxury of channeling his adventurous spirit into discovering the roots of mountain tunes. He began a wide range of musical ventures, drawing on his exposure to the mountain culture and his indefatigable energy. He recorded commercially through the twenties on Brunswick and OKeh labels and knew his contemporaries, Gid Tanner, John Carson, and Samantha Baumgarner, who were also trying their fortune with the budding industry.9 He wrote ballads and songs, often with current themes, but always in the traditional style. His most famous tune, “Mountain Dew,” described the moonshine business of those Madison County folk untouched by the labors of the Baptist preachers, Christian mission schools and the Methodist circuit riders:

There’s an old hollow tree up the way there from me

Where I lay down a dollar or two

I go away and then, when I come back again

There’s some good old mountain dew.

In 1925, Robert W. Gordon, a Harvard-trained folklorist, came seeking mountain songs for the Library of Congress. Bascom had been collecting extensively but needed the encouragement of Gordon. They traveled into the hollows together recording, and Gordon impressed upon Lunsford the importance of serious song collections. In 1929. Lunsford co-authored a small collection of original tunes, 30 and 1 Folk Songs. And in 1928, he directed the first Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville.

He launched into a new career as a folklorist because “I feared that, as the old folks passed on, they would take with them to their graves all memory of the tunes and lyrics which once the mountain people had sung with such joy and gusto.”10 He moved from being a one-man repository of the old tunes to a maturing professional. He learned folklore methodology and observed precise standards of collection. He still spoke as a folklorist at the end of his life:

. . . that’s the reason I always started the folk festival ‘‘along about sundown.” Certain expressions like that stick in a person’s memory and become strong. I always used that principle of folk tradition in my work.11

Lunsford’s pride in mountain music took him from coast-to-coast. He led a delegation to the first National Folk Festival in St. Louis in 1934. He lectured and sang at colleges throughout the country. In 1935, he recorded his personal collection of songs for the Columbia University Library in an astounding display of stamina and memory, and he sang before 16,000 people in New York’s Madison Square Garden when the National Folk Festival was held there in 1942.12

In 1949 Lunsford made recording history again with a seven-day marathon session for the Library of Congress in Washington, recording over 300 songs. This collection came from a variety of sources. In addition to childhood experiences and travels with the Nursery Company, he learned songs at parlor gatherings around the piano in such places as the sheriff’s house in Graham County, and he gave prizes for new songs written in the traditional style or the discovery of old ones when he lectured at schools on traditional music. These recordings are treasured for their authentic mountain diction and include such favorites as ‘‘Cindy,” “Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground,”, his own “Mountain Dew,” and a unique version of “Jesse James” which he learned in 1903 from Sam Sumner near Bat Cave, North Carolina.13 Other collections of Lunsford’s songs were made for the Library of Congress by Alan Lomax (1941 Asheville Festival), Frank C. Brown, and Benjamin Botkin.

Perhaps Lunsford’s finest hour came in 1939 when he took Sam Queen and his Soco Gap dance team to the White House to perform for the King and Queen of England. Lunsford leaned against the gold piano and picked his banjo while Sam Queen sang out “Walking the King’s Highway” to his cloggers. While the King smiled and the Queen patted her foot, Cordell Hull whispered to Lunsford that he could dance any figure they could.

The Asheville Festival

Lunsford became known worldwide for his music and his collections. However, the world of professionals is not the world of Madison County. Lunsford loved the Asheville Folk Festival above all else, and the Festival remains the most revealing and the most symbolic aspect of Lunsford’s career and his place in North Carolina folk tradition.

The Festival grew into the Civic Auditorium but did not “outgrow” its purpose. “Forty-six years I’ve never had a written program, never had a piece of paper in my hand. I know the fellers, knew what they played, knew how well they did it, you see.” People never wore cowboy hats or sang country and western music. Most of the performers were local and understood the tradition, but occasionally a young mis-guided initiate would arrive with an electric guitar or some yodeling numbers. Lunsford put them on first and most of the crowd came to realize that the real show did not start until about sundown, after these aberrations had come and gone. When mills came into the area and started sponsoring dance teams, Lunsford insisted that the teams continue to be called by their native region rather than by the name of any mill.

Musicians came mostly from western North Carolina and were not commercially famous. Some were well known to the supporters of the Festival and to those who lived in the area; Lunsford uncovered others and encouraged them to share their talents with the Festival audience. Wanting all of them to perform, Lunsford judiciously shied away from choosing a favorite when asked to name the best fiddle-player he had ever known:

When it comes to the best fiddle-players you have to name Marcus Martin of Swannanoa, Manco Sneed the Cherokee Indian, Dederick Harris from Whittier, Fiddlin Bill Hensley of Madison, Jesse Rogers of Henderson, and Pender Rector of Madison.16

Most of them made it to the Festival each year, some holding the fiddle against their chest in the traditional style rather than under their chin. Obray Ramsey from Madison, Red Parham from Sandy Mush, and Bill McElreath from Swannanoa were also regulars.

They would play old favorites of the highland fiddlers like “Sourwood Mountain,” “Cumberland Gap,” and ‘‘Old Gray Eagle,” and they sang traditional ballads like “Barbara Allen,” telling tales that might very well date from their European ancestors. Banjo players would add the driving rhythm of a mountain trailing or a clawhammer style to the background of the fiddle. The three-finger Scruggs style joined the other methods later so that now a banjo picker might use any of these three styles.

This strong local tradition did not discourage visitors however. They came from every state of the union, many coming year after year. In many ways the crowd at the Festival represented the same diversity of Lunsford’s native Madison County. Mountain musicians mixed with these summer tourists and local residents just as tourists frequented Hot Springs and educators built Mars Hill into a thriving college town in the midst of a rural mountainous county.

The Asheville Festival did not become another Union Grove festival, however, where thousands of young people flock to North Carolina’s foothills every Easter. Nor did the Festival become overblown as has the Grand Ole Opry, nor highly commercialized as have the burgeoning bluegrass festivals. In many ways, the Asheville Folk Festival stands somewhat apart from any other kind of mountain festival. Its closest kin is the informal music that is made on front porches throughout the region and such small festivals as those in Berea, Kentucky, and at Fiddler’s Grove, North Carolina.

Music in Mountain Culture

Lunsford came a long way from his cigar-box fiddle and his school-teacher parents but retained the ambiguities of these Madison County roots. His banjo and buck dancing reflected his lifelong contact with everyday people while his worldwide reputation as a folklorist represented the upward mobility of educated, mountain elites. This ambivalence remained unresolved, however. Lunsford defined his mission and proceeded with his goals, limiting the scope of his work to mountain music. Yet Madison County and the Appalachian region were changing rapidly, needing dynamic leaders as well as static heroes. The long verses of the English ballads lacked the contemporary poignance of protest songs from the textile and paper mills. These ballad tales reflected another era, important to be preserved, certainly, but maintained as a part of an ongoing folk tradition. And the times they were a-changing.

While Lunsford dealt exclusively with the music of the region, complex social forces were affecting the total cultural complexion of Madison County, western North Carolina, and all of Appalachia. The power of the media, the threat of assimilation, and the destructiveness of outside economic and political controls signaled real dangers. Lunsford’s responses to these perils were narrow when viewed within the context of his times.

The people of western North Carolina have traditionally shared the uniqueness of mountain culture with the rest of Appalachia. The Scotch, Irish, British, German, and Dutch settlers moved down the Blue Ridge chain from Pennsylvania and into the mountainous frontiers from the Virginia and North Carolina flatlands. This common heritage reinforced the bonds between these settlers; their struggles were against the elements of nature and the isolation of a frontier. Rooted in the commonality of this western migration, divergent economic and political forces swept into Appalachia, and North Carolina’s development took a separate course.

In the late 19th century the discovery of coal precipitated a major transformation of the mountain region. “Bloody Harlan” and Coal Creek symbolize the political struggles that ensued as mountain people reacted to the usurpations of the coal industry in Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, and southwest Virginia. From the first machinations used to steal people’s land, documented by Harry Caudill in Night Comes to the Cumberlands, to the most recent strip-mining fights, reported by “Mountain Life and Work” and “People’s Appalachia,” coal has been the focus of people’s anger and dissent.17 There have been many other struggles within the mountains, of course: abolitionists, unionists, CIO organizing efforts, and the welfare rights movement. However, the pervasive impact of the coal economy has made battles against the coal industry the dominant theme of mountain struggle.

The North Carolina mountains represent a starkly different image both in myth and reality. The myth pictures a placid and serene people unlike their Appalachian neighbors; a new history of western North Carolina opens, “Carolina mountain folk are not ‘yesterday’s people’ nor is night likely to come to them.”18 The reality is a complex history of economic exploitation and proud independence. Political and cultural struggle has lacked the dramatic focus of coal but has been no less crucial. In 1835, the treaty between the Cherokees and the United States legalized the Cherokees’ trail of tears to Oklahoma, yet a determined band remained and eventually secured reservation land in 1876 and was incorporated in North Carolina in 1889. Unionists and abolitionists were active in North Carolina although not as strongly as in Tennessee. When the National Forests and Great Smokey Mountain National Park came to the region in 1926, the independent mountaineers challenged the U.S. Government itself, refusing to leave their coves, some of them living out their lives there. The labor struggles of the late twenties and early thirties reached the North Carolina textile mill towns of Gastonia and Marion in 1929, and many people who had come from the mountains to these foothill towns were intensely involved in challenging the most powerful industry of the state. Other labor struggles of the 1940’s and 1950’s, often with strong interracial cooperation in CIO unions such as the old Fur and Leather Workers, resulted in the most heavily unionized area in this most unorganized state, with the Paperworkers in Brevard and Canton, the Rubberworkers in Waynesville, the Textile Workers in Enka, and the Meatcutters in Asheville.

More recently the Tennessee Valley Authority devised a plan to construct a series of fourteen dams on the headwaters of the scenic French Broad River, with potential flooding of 6,600 acres in Madison, Buncombe, Henderson, and Transylvania counties. The Upper French Broad Defense Association organized against the powerful TVA, using local sentiment in a public hearing in Asheville, the environmental impact statements required by the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, and organized citizen’s pressure on political leaders at all levels in the 1972 elections. In late November, 1972, the TVA announced that it was abandoning this $125 million project.

Without the natural ties to the coal economy of the rest of the region and without any continuity within its own political struggles, the mountain culture of North Carolina has evolved differently from the rest of Appalachia. Moreover, dynamics continue to pull North Carolina apart from the region. The political struggles, the folk traditions, and the “folk heroes” themselves have come to be viewed as much North Carolinian as Appalachian. The forces presently working against the people of western North Carolina are extremely subtle. The federal government (National Forest, National Park, and TVA) owns an enormous amount of land, eroding the property tax base of the six western most counties by about 50% — yet at the same time these lands are protected from developers. Interstate 40 ploughs straight through the mountains now, accentuating the mobility of the American middle class, and the tourist economy created by this travel results in low-paying, seasonal jobs, and ecological disasters, as billboards and neon signs obscure the natural beauty of the mountains. Corporate developers search frantically for new sites for chalets, resort hotels, and amusement parks. And utility companies have sighted the less populous mountain region for new projects, including the Blue Ridge power project of the New River, which will flood parts of three counties in North Carolina, and a smaller nuclear plant planned for Madison County.

These forces are at work in Lunsford’s native Madison County. The small population peaked in 1940 and has been declining since. Moreover, a larger percentage of the 16,000 people today commute to the Asheville area for industrial jobs with fewer independent farmers, and especially their children, remaining on the land. The data of the North Carolina Employment Security Commission clearly reveals the employment situation in this rural area:

Percentage of Civilian Work Force Unemployed

Year Madison Co. Buncombe Co. (Asheville) North Carolina

1970 11.1% 3.4% 3.8%

1971 12.7% 3.6% 3.9%

1972 8.7% 2.4% 3.1%

To alleviate this high unemployment, a standard formula reappears in local government and chamber of commerce publications: “One of the prime areas of potential development in western North Carolina as a whole, including Madison County, is the area of recreation and tourism industries.”20 Developers are responding to these “invitations” with such ventures as “Wolf Laurel” in the Bald Mountains area of Madison, a project with second-home plots and a luxurious golf course.

For all of its distinctiveness, however, western North Carolina’s heritage must remain within the Appalachian region or be assimilated into the growing homogeneity and rootlessness of contemporary American culture. The ethos of the Asheville Folk Festival must find a sense of kinship with labor struggles within the coal regions as well as with the expanded minds and visions of Elliot Wigginton’s students in North Georgia and with those who come through the educational work shops of Highland Center in East Tennessee. Folklorists and political activists throughout the mountains cannot afford to view one another with parochial disdain or to dismiss each other as irrelevant. The corporate enemies are too sophisticated to be fought alone. They are controlling policy makers of television networks who encourage the proliferation of the destructive stereotypes of Green Acres and Beverly Hillbillies;21 they are board members of New York holding firms controlling strip-mining decisions in Washington, in Frankfort, and in Charleston; and they are wealthy financiers looking beyond Miami Beach and the Colorado ski resorts to such land grabs as the 1973 Mead Purchase of 35,000 acres in Jackson County, North Carolina.

The limits of Bascom Lamar Lunsford as a folk hero become clear in this cultural and political context. His was not a voice of political struggle; he did not involve himself in the labor struggles of the thirties or forties, nor did he often speak out against the potential dangers of land development. In fact, he disapproved of the political music of great balladeers like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.22 Lunsford lived with integrity and purpose; he nurtured the natural bonds that an indigenous musical tradition creates between people. But his personal history, his times, and his narrow concern for music limited his perception of the complex forces eroding the social base of the very culture he wished to preserve.

Good-byes

The Forty-Sixth Annual Mountain Dance and Folk Festival was drawing to a close. The interaction of musicians and audience, local folk and visitors, had continued throughout the evening—from the rain-soaked ticket lines to the final goodnights. The hours had been full with fiddle tunes and ballads, string bands and clog teams, tributes for those who had passed away, and anticipations of what was to come with youngsters performing as well as any of the oldtimers. Lunsford introduced several opening numbers but quickly retired to a seat on the edge of the stage and turned the proceedings over to his son, Lamar.

The casual mingling on the stage of musicians, square dancers, and friends extended into the audience as the evening progressed. After the winners had been announced and people had started to leave, these interactions culminated with a community buck dance on the performing platform in front of the stage. The Festival seemed complete: distance between performers and the listeners diminished as people throughout the auditorium participated in this final number, skilled and unskilled clogger alike.

The music was over and the crowd dispersed. As we drove north to Madison County, the downpour had calmed to a drizzle, and the darkness of the night lightened the impact of Asheville’s urban sprawl. When we reached our camping spot in a cove in Little Sandy Mush, the early morning dew had added a freshness to the mist of the lingering storm, and the ring of the banjos was still with me.

The morning clearly revealed Asheville’s sprawl, however, and the ambiguities of the music’s impact on mountain culture weighed on me. We stopped in one of the numerous roadside groceries before returning home. This hiatus allowed for one more moment as an insider: I recognized the caller for the winning clog team and offered several suggestions. We shared some subtle steps on the concrete floor; he marveled at such skills, having seen our license plate. I wished for the precision of the old Hendersonville clog team, and he promised to do better. As we headed for Interstate 40, the monolithic link between Sandy Mush and the outside, I wondered about his role in the mountains—and mine.

The limitations of Lunsford as a folk hero remain with all of us, those who can clog and those who cannot, for a new section of 1-40 just opened and western North Carolina land has become some of the most sought-after resort and development real estate east of the Mississippi River. We must move beyond these limitations, insider and outsider alike. We must work to create a more substantial cultural unity between the complex political struggles of the mountains and the subtle values of folk tradition. For the dichotomies that have often separated these two traditions can move forward with the power to preserve and the power to change.

Footnotes

1. Bob Terrell, Asheville Citizen, September 5, 1973.

2. Author’s interview with John Parris, March 25, 1974.

3. John Parris, Asheville Citizen, July 26, 1965.

4. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce.

5. John Parris interview.

6. Harold Martin, Saturday Evening Post, May 22, 1948.

7. Author’s interview with Loyal Jones of Berea College, April 2, 1974. Mr. Jones has been chosen by the family to be Lunsford’s biographer.

8. Manly Wade Wellman, Kingdom of Madison, Chapel Hill: U.N.C. Press, 1973, p. 142.

9. Ann Beard, The Personal Folksong Collection of Bascom Lamar Lunsford, M.A. thesis, Miami University, 1959.

10. Obituary, Asheville Citizen, September 5, 1973.

11. Terrell, Asheville Citizen.

12. Beard and Obituary.

13. “Bascom Lamar Lunsford,” introduction to his recording, Archive of Folk Song, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

14. Beard, op. cit.

15. Obituary, op. cit.

16. John Parris, Asheville Citizen, March 24, 1974.

17. For more information on the historical and current impact of the coal industry on mountain culture see Southern Exposure, Vol. I, No. 2, and No. 3-4, and David Whisnant, “The Folk Hero in Appalachian Struggle History, New South, Vol. XXVIII, No. 4.

18. Cratis Williams, introduction to I.W. and John J. Van Noppen, Western North Carolina Since

the Civil War, Boone, N.C.: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1973, p. x.

19. Author’s interview with Charles Taylor, financial investor for Brevard, North Carolina.

20. County Facilities Plan, North Carolina Department of Local Affairs, 1971, p. 6, and numerous other similar publications, such as: Environmental Survey and Plan, N.C. Division of Community Services, 1972; Land Development Plan for Madison County, Dept, of Local Affairs, 1970; Overall Economic Development Program for Madison County, Western North Carolina Regional Planning Board, 1961.

21. David Whisnant develops this theme as a part of his multi-media presentation of folk and political heroes in Appalachia.

22. Loyal Jones interview.

Tags

Bill Finger

In 1963, the year Mississippi State faced Loyola in the NCAA, Bill Finger was playing high school basketball in Jackson. He is now a freelance writer in Raleigh, NC, and at work on a book about the players of those historic teams. (1979)

Bill Finger is a writer in Raleigh, NC. (1978)

Bill Finger is the labor editor of Southern Exposure. (1976)

Bill Finger is the Director of the Institute for Southern Studies Textiles Project. He has worked for the North Carolina AFL-CIO and the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina. (1976)