This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

Anyone involved in organizing that challenges the established order may find the battle getting tougher as those in power feel more and more threatened. The re-emergence of right-wing politicians, surveillance agencies and terrorist activities by racist organizations is a new incentive for progressive activists to study past methods of infiltration and disruption by official and quasi-official power.

The following interview with Ken Lawrence highlights the role of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission and offers important lessons for understanding how state agencies act to thwart the Movement, including the use of informants, smear tactics, internal frictions among civil-rights groups, the press and red-baiting. Documents featured here focus on the Commission’s activities to counteract the “Freedom Summer” organizing campaign of 1964, the development of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and the Meredith March Against Fear in June, 1966, during which the concept of black power first became popular. (For more on these events, see Southern Exposure’s “Stayed on Freedom,” Vol. IX, No. 1.)

The methods and effectiveness of the Sovereignty Commission parallel the FBI’s now infamous Counter- Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO). But the Sovereignty Commission began its program against the black movement several years before J. Edgar Hoover instructed his agents to “prevent the rise of a messiah” who might lead a black revolution.

Ken Lawrence has been researching the activities of the intelligence agencies in Mississippi and elsewhere for 10 years, and is a plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against the Sovereignty Commission and other agencies that conduct surveillance of political activity, filed in federal court by the ACLU of Mississippi. He is now director of the Jackson-based Anti-Repression Resource Team, and was formerly on the staffs of the Southern Conference Educational Fund and the American Friends Service Committee. He was interviewed for Southern Exposure by Ashaki M. Binta, a Mississippi-based free-lance journalist, activist and former labor organizer.

The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission was created by a 1956 act of the legislature which states that, “It shall be the duty of the commission to do and perform any and all acts and things necessary and proper to protect the sovereignty of the State of Mississippi, and her sister states, from encroachment thereon by the Federal Government or any branch, department or agency thereof; and to resist the usurpation of the rights and powers reserved to this state and our sister states by the Federal Government or any branch, department or agency thereof.”

Naturally that meant, in those days, denial of political rights to black people — one Jackson newspaper called it “counter-intelligence activities against forces seeking racial integration.” The Commission was given subpoena power and the authority to enforce its subpoena with the threat of fines or imprisonment. In that sense it was a state witch-hunting agency modeled after the House Un- American Activities Committee and the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee; nearly every other Southern state followed the Mississippi model. But the Commission was much more than that.

In the early ’60s, it was a propaganda agency. The Sovereignty Commission produced a film called “A Message from Mississippi.” Erie Johnston, Governor Ross Barnett’s top campaign aide and editor of the Scott County Times, joined the Sovereignty Commission staff as a public relations officer, even though he had condemned it editorially at the time it was created. He had the film made in his home town of Forest. Its message was that Forest was an ideal, racially segregated community, and that both black and white people loved “the Mississippi way of life.”

The Sovereignty Commission sent that film up North, and later another one, “Oxford, U.S.A.,” which blamed “outside agitators” for the violence that ensued when Governor Barnett, backed by armed white vigilantes, attempted to prevent James Meredith from enrolling at Ole Miss. The Sovereignty Commission also sent prominent speakers to the North to promote segregation: one was Alvin Binder, a leading Jewish attorney from Jackson. Another was Rubel Phillips, the state’s leading Republican, who was later sent to prison for his part in a stock swindle. The Commission prepared speeches for its representatives and written questions and answers for the press to use.

It was also a lobbying agency, and was instrumental in establishing and funding the Coordinating Committee for Fundamental American Freedoms in Washington to act as a clearinghouse for opposition to federal civil-rights legislation. The Sovereignty Commission gave $10,000 of its own appropriation and raised another quarter million toward this effort, including a $50,000 direct grant from the Mississippi legislature.

The Sovereignty Commission never claimed to be impartial. Not only did it never investigate the ultra-right, it actually contributed large sums of money — $193,500 over a four-year period — to the white Citizens Councils. Over the years a number of Citizens Council members served on the Sovereignty Commission, and one legislator who served on the Commission, Tommy A. Horne of Meridian, had been arrested in the ’60s in connection with the 1964 Ku Klux Klan murders of three civil-rights workers in Neshoba County — Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.

At its height the Sovereignty Internal documents of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, reporting infiltration of Commission claimed it had files on civil-rights groups’ planning sessions 250 organizations and 10,000 individuals. This information was disseminated to state agencies, prospective employers and newspapers, and in whatever ways would disrupt the Movement.

The Sovereignty Commission was abolished by the legislature in 1977, after we filed our lawsuit. The files were ordered sealed and deposited in the Department of Archives and History. The law makes it a crime to “willfully examine, divulge, [or] disseminate” the documents, so by publishing these documents we may be risking three years’ imprisonment and a $5,000 fine — of course, the law is ridiculous and unconstitutional.

Actually the Sovereignty Commission had ceased to function four years earlier when Governor Bill Waller vetoed its appropriation. In his veto message, Waller said the Commission’s work is now being done by the Department of Public Safety and the Attorney General’s Office. We know that’s true because we’ve seen Highway Patrol investigators spying on United League marches, and the Attorney General’s Organized Crime Intelligence Unit has reported investigating several groups in Mississippi, including the Republic of New Africa.

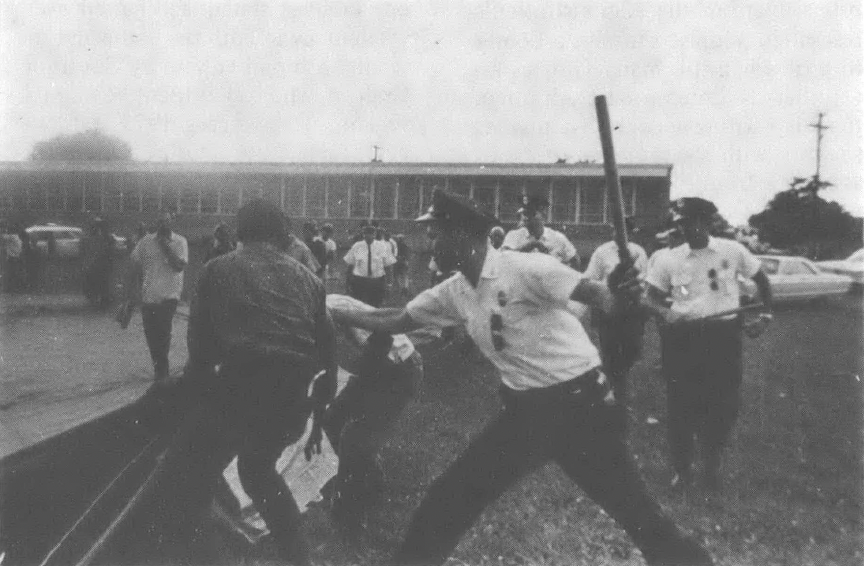

The Sovereignty Commission documents are spy reports gathered by the Movement’s enemies. They can’t be taken at face value; all secret police files are full of distortions and inaccuracies, and these are no exception. The documents for the Meredith march were gathered in the summer of 1966; a number of civil-rights activists were campaigning for public office as Freedom Democrats, and the state was trying to discredit them. While that was happening, James Meredith began his march, and while walking in the Delta was shot. The eyes of the nation were focused on Mississippi once again, as they had been two years earlier during the Mississippi Summer, and the leaders of various organizations vowed to pick up the torch from where Meredith fell and carry on to Jackson.

It was through the surveillance of Reverend Edwin King’s campaign for Congress as a Freedom Democratic Party [FDP] candidate that the Sovereignty Commission spies first learned of the plans for the march, and from there they went into action. The Commission had two spies at a relatively small campaign meeting on June 6, 1966, the day Meredith was shot. As you can see from the docu- ments, they were most concerned about finding divisions within the Movement. Both reports take the fears of older and more conservative members of the Movement about the militancy of the younger SNCC activists at face value, and report them as fact.

On June 9, the Sovereignty Commission’s spies reported that the Deacons for Defense and Justice of Bogalusa, Louisiana, planned to participate in the march as a security force. In the event that the marchers were attacked as Meredith had been, the Deacons would provide armed protection. Immediately the Commission took an interest in identifying cars bearing Louisiana tags. From then on, the file contains almost daily reports of the comings and goings of march leaders, debate over the Black Power slogan, concern with the activities of “mixed couples,” and other topics of discussion — no matter how trivial. One irony is that even Movement fliers and handouts bear the Sovereignty Commission’s RESTRICTED rubber stamp. Certainly the reports helped the state plan its public relations counterattack. Using information furnished by the Sovereignty Commission, Senator James O. Eastland made a speech charging that 11 communists participated in the Meredith March. And people were “punished” for their participation later on. This is one of the important functions of political intelligence-gathering; Frank Donner, author of The Age of Surveillance, one of the best books on the subject, calls this the doctrine of deferred retribution.

A perfect example of this is a lengthy article titled “Professional Agitator Hits All Major Trouble Spots” in the August 18, 1966, Jackson Daily News; it is a smear story, together with pictures, of Jo Freeman, who at that time was a civil-rights worker in Grenada, Mississippi. Among other things, it focuses on her participation in the Meredith march. In an internal memo, Sovereignty Commission Director Erie Johnston wrote, “We furnished the local press photos and background information on a young white woman who had been active in the agitation in Berkeley, California, Alabama, and Mississippi. The photos and stories about her were given wide publicity and eventually she left the state.” A source at the paper confirmed to me that this is a reference to the article about Jo Freeman.

During the summer of 1964, the Sovereignty Commission was trying to counterattack the Freedom Summer civil-rights workers. As usual, redbaiting was considered the most effective approach. Newspaper stories inspired by the Commission appeared in the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, including a pair of stories late that summer, headed “Freedom Group Linked to Communist Fronts.” Their appearance coincided with the Freedom Democratic Party challenge to the state’s regular delegation to the Democratic national convention in Atlantic City.

Again in 1965, when the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights was holding hearings on the denial of voting rights in the state, stories appeared in the papers red-baiting the FDP. The same thing happened in June, while the Mississippi legislature was considering proposed constitutional amendments to limit voting rights, and in October, when the national spotlight was on the House Un-American Activities Committee’s investigation of the Ku Klux Klan. Each time, the idea for the stories originated with the Sovereignty Commission.

The Sovereignty Commission also claims credit for getting the presidents of two private black colleges fired. They intervened in the election for editor of the Ole Miss student paper and smeared one of the candidates, Billy Barton, as a “liberal” — a false charge as it turned out. They covertly supported one Headstart program — Mississippi Action for Progress [MAP] — against another — the Child Development Group of Mississippi [CDGM] — because MAP was firmly in the grip of “moderate” leaders while CDGM was a grass-roots program organized by militants and run by poor people. They tried to prevent the federal government and private foundations from giving money to programs where Movement militants held influence. They worked with officials at the University of Southern Mississippi to prevent the ACLU from establishing a chapter there.

But exploiting internal differences was the main approach, just as it was for the FBI. A couple of years ago, I taped an interview with Erie Johnston, who is now in retirement, about his years with the Sovereignty Commission. He bragged to me that civil-rights groups often fought each other, and that sometimes one would involve itself with the Sovereignty Commission in the course of its factional maneuvering — “very under the table,” he said (see box).

We don’t know who the agents were who filed the reports on the Meredith march. The Sovereignty Commission had full-time staff investigators and paid informers. Erie Johnston told me they all had code names, so only he knew the identities of the infiltrators. They also used electronic surveillance.

Ralph Day, the head of Day Detectives and a member of the Citizens Council, has testified in our lawsuit that he conducted investigations for the Sovereignty Commission. Erie Johnston says Day was not really an investigator, just a conduit to pay agents so their names wouldn’t appear on any official records. That was a serious problem for them, because during the Commission’s early years enterprising reporters had learned through the records at the State Auditor’s office that the publishers of two black newspapers — Percy Greene of the Jackson Advocate and Reverend J. W. Jones, who put out a small paper in New Albany — were both on the Sovereignty Commission payroll.

Information was also shared between the Sovereignty Commission and other intelligence agencies. The best documentation I’ve seen concerns political surveillance during the Republic of New Africa trials in 1972; at that time intelligence was shared among the Jackson Police Intelligence Division, the Hinds County Sheriffs office, the FBI, the U.S. Marshal’s office, the Highway Patrol, the Attorney General’s Organized Crime Intelligence Unit, the Chicago Police Red Squad, and the Sovereignty Commission. At other times, they’ve worked with the Justice Department’s Community Relations Service and agents of the Treasury Department.

We’re not sure about contacts with the CIA, but former CIA director Allen Dulles did meet with Sovereignty Commission director Erle Johnston in 1964.

Erle Johnston claims the FBI is a “one-way street,” meaning they accept information from agencies like the Sovereignty Commission but don’t release information from their own files. I have seen evidence, however, that the FBI did open its files to the Sovereignty Commission. It was an instance where the FBI had tried to discredit a certain leading civil-rights figure by gathering evidence to show that certain minor federal regulations had been violated. When the U.S. Attorney refused to prosecute because the evidence was insufficient, the FBI then opened its files on the case to the Sovereignty Commission, which in turn passed the information on to smear the leader.

The Sovereignty Commission had other targets besides civil-rights and Black Power groups. They included the ACLU and militant organized labor. The documents we have show that the Sovereignty Commission was especially worried about the 1971 strike of the Gulfcoast Pulpwood Association [GPA], an organization of woodcutters assisted by SCEF. The spy reports on the strike are quite detailed, and we all had a good laugh when we saw what the November 19, 1971, minutes of the Commission said about SCEF’s role in the strike:

“SCEF’s primary objective is to work with both blacks and whites and get them integrated and united to work together. They have been successful in getting some of the Klansmen to say, ‘Sure, we used to be against the Negro, but we were wrong.’” You can see what really frightened them.

Shortly after the strike began, a long editorial red-baiting the GPA and SCEF appeared in the Jackson Daily News, titled “Carl Braden Stirs Strife in Laurel Pulpwood Fracas.” It was accompanied by a cartoon showing a stack of logs labeled “Laurel Pulpwood Agitation” with a hammer and sickle beneath them. The editorial had lengthy quotes from a recording of one of the strike meetings.

This may have come from the Sovereignty Commission, though in this instance my source wasn’t certain. It may also have been prompted by the FBI; there are a number of instances in which the Daily News ran smear stories as part of FBI COINTELPRO operations.

These activities are still going on, but different agencies are doing them now. A few days after we filed our lawsuit against these agencies, the head of the Highway Patrol tried to smear me to a television reporter. Unfortunately for him, the reporter was a friend of mine.

A Spymaster Speaks

Erle Johnston, Jr., was publicity director of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission from 1961 to 1963 and its director from 1963 to 1968. He was editor of the Scott County Times from 1942 until his retirement in 1979. Recently, he published a memoir of his years as a political insider with former Governor Ross Barnett, I Rolled With Ross. Ken Lawrence interviewed Johnston in his newspaper office in Forest on October 31, 1978. Here are a few excerpts from the interview.

I called myself in those days a practical segregationist.

You have got to have informants. If you are trying to fight anything you consider alien to law or alien to custom, you’ve just about got to have people who’ll tip you off about what’s going on. If you didn’t, you’d spin a lot of wheels over nothing.

Keep in mind that even among the so-called civil-rights groups that they were fighting each other a lot of times, and they would try to use us to undermine others sometimes, you know, very under the table.

The last years we were looking more for subversives as opposed to integrators. After all, integration wasn’t against the law, but subversives, the people who were on the House Un-American list or on the Senate Security list — names of people and names of organizations which were public record — and you know a lot of times some of those people would be in Mississippi, and they might try to stir up the colored race to doing something. Well, if we could find out their background, expose them for what they represented, a lot of times they lost their influence. The colored were not — in other words, if anybody looked communistic, they wouldn’t go along with him.

Sometimes there would be one person in the whole town who would be the troublemaker. And sometimes you’d have to figure out a way to get him to move somewhere else.

You know good and well that the Sovereignty Commission could not have called Washington and said, you know, “We don’t like this outfit, and this outfit.” That would be just like the kiss of death, you know. So the only thing we could do would be, through our investigative channels, try to find out if there were what we might call irregularities on one or the other, and then try to get them in our hands whichever way we could.

Tags

Ashaki M. Binta

Ashaki Binta is also a former Senior Field Representative of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and Associate Director of the Brisbane Institute/Southern Center for Labor Education and Organizing (SCLEO). Additionally, she serves as Director of Organization for the Black Workers For Justice. (1998)

Ken Lawrence

Ken Lawrence, 42, is a writer and activist living in Jackson, Mississippi. He is a long-time friend of the Institute for Southern Studies. Dick Harger, 50, teaches psychology at Jackson State University. Both have been friends of Eddie Sandifer for many years. (1985)

Ken Lawrence, formerly staff writer for the Southern Patriot, is a long-time Mississippi activist, researcher, and writer. The two italicized interviews included here originally appeared in the Southern Patriot, the old SCEF newspaper, in 1972. They were conducted by Ken Lawrence. (1983)