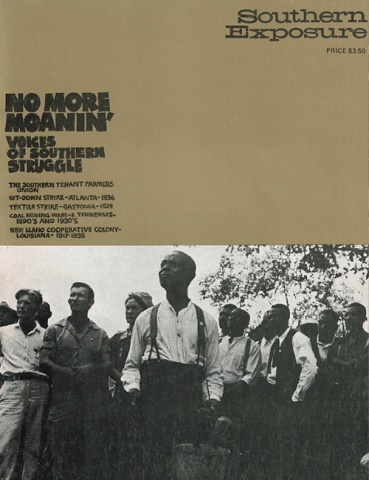

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 3/4, "No More Moanin'." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

One of the recurring themes in the genesis of racism in the United States is that contributions to American civilization and culture pioneered by black people are appropriated by white society. Often the development is further distorted by crediting individual whites with the particular gifts or discoveries.

One example of this is the case of oral history. The techniques which are today known as oral history were originally developed and refined in the late 1920’s by historians at Southern University and Fisk University in order to study the largely illiterate population of former slaves—American slavery from the viewpoint of its victims.

Their original work was further advanced and developed when a project of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration collected interviews with 250 ex-slaves in Kentucky and Indiana in 1934, and when the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Projects Administration (WPA) collected over 2,000 interviews with ex-slaves from 1936 to 1938.

Despite these massive projects by hundreds of historical workers over most of a decade, credit for the existence of today’s oral history “movement” is most frequently assigned to two white historians associated with Columbia University, even by commentators who know better, despite the fact that the Columbia project did not begin until 1948.

The record is gradually being set straight, largely due to the recent appearance of popular editions of books (including some old ones) based upon the slave narratives. These include Benjamin Botkin’s Lay My Burden Down, A Folk History of Slavery; the Georgia Writers’ Project’s Drums and Shadows, Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes; Julius Lester’s To Be a Slave; and Norman R. Yetman’s Voices From Slavery.

The most massive and complete product of these early oral history collections is The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography by George P. Rawick. So far nineteen volumes have appeared, and more are expected. Sixteen of these contain the Federal Writers’ Project Slave Narratives, and two are reprints of the Fisk University collections, Unwritten History of Slavery and God Struck Me Dead.

Rawick’s introductory volume, From Sundown to Sunup, The Making of the Black Community, has been called “the most valuable book I know of by a white man about slave life in the United States” by Eugene D. Genovese, himself a prominent historian of slavery. It is a challenge to almost all previous histories that were based primarily on accounts of slavery written by slaveholders and journalists.

Rawick says that historians have been aware of the existence of slave autobiographies and narratives for a long time. But in almost every case white historians have chosen to believe the account of white oppressors or casual observers, rather than to rely on slaves’ descriptions of their own lives.

Not only does Rawick challenge the openly racist view presented by Stanley M. Elkins in Slavery, A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life; he also uses the evidence of the narratives to repudiate the liberalism of Kenneth M. Stampp, whose book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante- Bellum South, views black people as “only white men with black skins.”

In the past, the strongest challenges to the racist histories of slavery were Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, by W.E.B. DuBois, and Herbert Aptheker’s American Negro Slave Revolts. Rawick’s work supplements these by showing that the struggles waged by slaves in their daily lives provided the groundwork for the pitched battles described by Aptheker, and the revolutionary overthrow of slavery documented by DuBois.

• • • •

During a trip to Mississippi last year, Rawick challenged audiences on several campuses to advance this work by locating the lost narratives. He pointed out that his source, the material microfilmed by the Library of Congress, provided only 174 pages of Mississippi narratives, and that there must have been a great deal more collected by the WPA. He was correct. A careful search of WPA materials by the staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History turned up nearly 2,000 additional pages, apparently unused by scholars.

In addition to the obvious value of this material as a rich new source for historians of slavery in Mississippi, the collection reveals a lot about the narrative collection as a whole, particularly the ways in which the racism of the WPA interviewers and editors (mostly white women) intervenes in the collection. For example, this particular collection includes several different versions of some narratives, making it possible to see how dialect changes were added to later versions of some, apparently to match an editor’s idea of vintage Uncle Remus. (This fact may suggest needed modifications of language studies based on the narratives. For example, J.L. Dillard’s book, Black English, Its History and Usage in the United States, relies heavily on the narrative selections in Botkin’s Lay My Burden Down.) One file even contains a note by an interviewer complaining that “my darkies” don’t say things according to “Washington’s idee.”

• • • •

Another example of this problem is deleted material. One of the narratives in Rawick’s collection (The American Slave, volume 7, Oklahoma and Mississippi Narratives) is Pet Franks’ story, told to Mrs. Richard Kolb. The Library of Congress copy, reproduced by Rawick, is similar to the version in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, but leaves out the following text:

I recollect one time when dere was snow on de groun’ and it was freezin’ cold and in de middle of de night we beared somebody a knockin’ at de door and when my pappy got up dere was a nigger man out in de cold without no shoes on and with mighty few other clothes on. He said he was freezin’ to death. My mammy got up and did all she could to help him but his feet was froze and two of his toes dropped off when dey thawed. Next mawnin’ we called de mistress out to see him and she jest natchally cried when she look at him. When she found out whar he come from she made de marster hitch up de surry and go carry him back and de marster say he was gwine turn that owner over to de law or know de reason why. But ’fore he got there de nigger had done died.

“I member ’nother time but dat was durin’ de war when I was ridin’ on my horse over to Columbus to carry some clothes to de soldiers. On de way back I beared a bell ringin’ and I think it must be a cow strayed off but when I look I sees a nigger man with his hands in a iron halter up ’bove his head and a bell strung ’tween them. He say his marster had beat him and den for two days had kept his hands and feet nailed to a board, you could see de nail holes too, and den had put his arms in dat halter and turn him loose. He say it was all cause he marster beared tell dat he say he would be glad if de Yankees won de war so's he could be free.”

In another WPA file, one editor wrote to another, “It seems that the story of the Negro uprising should give more testimony in favor of the white men—from merely reading the story it might give some damn Yankee, even to-day, a good excuse to complain of the treatment accorded to the Negroes in those days. The gory details of the execution are given but the untold horror of a possible Negro rule, as people saw it in those days, should be made clearer for the benefit of readers whose grandfathers did not take part in all this.” The note refers to a manuscript of Civil War and Reconstruction folk tales by Mississippi writer Hubert Creekmore.

• • • •

Following is the narrative of Lizzie Williams, an ex-slave interviewed by Vera Butts in Calhoun City, Mississippi, in 1937. As a selection, it is not typical of the collection as a whole. Rather, it is archetypical—that is, many of the things she speaks about are similar to selections to dozens of other narratives in the collection: her description of the slave quarters, how children were fed, the clothes worn by slaves, the duration and amount of labor, the method of whipping a pregnant woman, and so on—regarding the treatment of slaves. This is one of the many “lost” narratives in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History collection. Introductory comments are by the interviewer:

LIZZIE WILLIAMS, ex-slave. Age 88 years, height 5 feet 2 inches, weight 110 lbs., health bad; almost blind, general coloring black. Apparently an honest up-right negro who has always worked hard and once was financially able to enjoy the necessities of life but today, due to misfortunes of various kinds, is without means of actual necessities. No children able to give her sufficient support.

“I was 88 years old de furst day o’ dis past June. Was born in Grenada county, five miles dis side [east] o’ Graysport.

“My Mammy was Mary [Pass] Williams an’ I had fourteen brothers an’ sisters but deys all dead now ’cept me.

“My Mars a was Capt. Jack Williams an Capt. Jacks Mammy, Miss Lourena Williams, was my Missus. Capt. Jack, he never did marry. He owned ’bout 1400 acres land, ten or fifteen grown nigger men what was called de plowhands an’ lots o’ fifteen an’ sixteen year old boys 'sides de women an chillun.

“Back in dem days we lived in little log houses dob bed with mud an’ had dirt floors. Dey was covered with boards an’ waited down with plank to keep 'em from blowin’ off. We slept on a quilt spread on de ground fo’ our bed.

“My job back in dem days was to weave, spin thread, run de loom, an durin crop time I plowed an’ hoed in de field. My mammy was a regular field hand.

“Marsa he was good to us niggers, he never would whip us. De overseers was a Mr. Gentry, Vanvoosa an’ Hamilton an’ dey would sho get holt o’ us if we didn’t work to suit em.

“Dey didn’t give us nothin much to eat. Dey was a trough out in de yard what dey pured de mush an milk in an us chillun an de dogs would all crowd ’round it an eat together. Us chillun had homemade wooden paddles to eat with an we sho’ had to be in a hurry 'bout it cause de dogs would get it all if we didn’t. Heep o’ times we’d eat coffee grounds fo’ bread. Sometimes we’d have biscuits made out o' what was called de 2nd’s. De white folks alius got de lst's. De slaves didn’t have no gardens but ole Missus gave us onion tops out o’ her garden.

“We sho didn’t have ’nuff clothes to wear back in slavery days neither. De ole shoe maker on de place made every nigger one pair shoes a year an’ if he wore ’em out he didn’t get no more. I’s been to de field many a frosty mornin' with rags tied ’round my feet.

“De overseer sent us to de field every mornin’ by 4:00 o’clock an we stayed 'till after dark. By de time cotton was weighed up an supper cooked an et, it was midnight when we’d get to bed heep o’ times. Dese overseers saw dat every nigger got his 'mount o' cotton. De grown ones had to pick 600, 700 an 800 pounds a day an’ de 14 an 15 year old ones had to pick 400 an 500 pounds.

“Twasn’t much sickness back in slavery days 'cept when de women was confined an' ole Missus an a nigger woman on de place tended to such cases. I 'member once my Mamma had to wash standin’ in sleet an ’ snow knee deep when her baby was just three days old. It made her sick an she almost died. Dats de only time dey ever was a doctor at any us nigger houses. Ole missus generally got Jerusalem weed out o' de woods an’ made syrup out o’ it to get rid o’ de worms in de chillun. She'd give calomel in 'lasses when we needed cleanin’ out.

“I’s seen heep o’ niggers sold. De white folks would put pieces o’ quilts in de mens britches to make em look like big fine niggers an’ bring lots of money.

“I seed one woman named Nancy durin’ de war what could read an 'rite. When her master, Oliver Perry, found dis out he made her pull off naked, whipped her an den slapped hot irons to her all over. Believe me dat nigger didn’t want to read an 'rite no more.

“Peeple dese days is in Hebben now to what we was in dem times.

“I’s seen nigger women dat was fixin’ to be confined do somethin’ de white folks didn’t like. Dey would dig a hole in de ground just big ’nuff fo’ her stomach, make her lie face down an whip her on de back to keep from hurtin' de child. Lots o’ times de women in dat condition would be plowin', hit a stump, de plow jump an’ hurt de child to where dey would loose it an law me, such a whippin as dey would get!

“We went to preachin’ at de white folks church. De preacher would preach to de white folks furst den he’d call de niggers in an preach to us. He wouldn’t read de Bible he’d say: ‘Obey yo’ Missus an’ yo Master.’ One ole nigger didn’t have no better sense dan to shout on it once.

“When niggers died you could hear someone goin' on de road singin’: ‘Hark From de Tomb de Mournful Sound.’

“I’s seen de patrollers whip niggers an dey would alius put his head under de rail fence an whip him from de back. We used to sing a song like dis: ‘Run nigger run de Patrollers will catch you ’tis almost day.'

“When de war was over Marsa come told us niggers we was free but said if we’d stay on with him de cotton money would be divided out between us niggers. Shore 'nuff Marsa sold dat cotton an ’fore he could divide it out his sister, Miss Bitha, stole it. Finally he got a little o' it an’ give it to de niggers. Some o’ em took it an aint been back since. We stayed on there three years. Finally Capt. Jack give his niggers land an dey just stayed on with him.

“My furst husband was Bob Pittman an our only child died. My next one was George Jean an our only child died. Den I married Hilliard Williams an we had 14 chillun an' raised em on Capt. Jacks place. Only four livin' now. Dey is day laborers, a preacher an a farmer. Me an my ole man lived together 50 years. He died in 1927. We was de founders of de colored Methodist church at Big Creek."

Tags

Ken Lawrence

Ken Lawrence, 42, is a writer and activist living in Jackson, Mississippi. He is a long-time friend of the Institute for Southern Studies. Dick Harger, 50, teaches psychology at Jackson State University. Both have been friends of Eddie Sandifer for many years. (1985)

Ken Lawrence, formerly staff writer for the Southern Patriot, is a long-time Mississippi activist, researcher, and writer. The two italicized interviews included here originally appeared in the Southern Patriot, the old SCEF newspaper, in 1972. They were conducted by Ken Lawrence. (1983)