Our Place was Beale St.

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 3, "Passing Glances." Find more from that issue here.

Robert Henry

JUDGE HARSH BLUES

They arrest me for murder, I ain’t harmed a man,

Woman’s hollering murder, I ain’t raised my hand.

Please Judge Harsh, make it light as you possibly can,

Cause I ain’t done no work, Judge, since I don’t know when.

—Furry Lewis

Beale Street runs from the Mississippi River out into East Memphis for nearly a mile, but for most people in Memphis, Beale Street means the four blocks between Hernando and First. It is this section that used to be “the black folks’ downtown” — the trade and recreation center for the black community of Memphis, as well as for the country people who periodically traveled to the city from eastern Arkansas, northern Mississippi and western Tennessee.

Within this four block stretch were pool halls; bars and clubs; gambling and prostitution houses; movie theatres; doctors’, lawyers’ and dentists’ offices; pawnshops, dry goods stores; hotels; boarding houses, even chop suey joints. But Beale Street was most famous for the musicians who played its clubs and for the music publishing houses and recording studios which made famous such names as W. C. Handy, Furry Lewis, Booker White, B. B. King and Elvis Presley.

Today Beale Street is closed down and boarded up. Although it has been designated a national landmark, its future is uncertain. In the Spring, 1977, issue of Southern Exposure, David Bowman documented a pattern of mismanagement by the city and private developers following Memphis Mayor Edmund Orgill’s 1959 announcement that Beale Street would be converted to a major tourist attraction. Almost two decades later, buildings have been torn down and people relocated, but redevelopment has not occurred.

Beale Street, however, continues to live in the memories of the musicians, shopkeepers and street people who knew it in its heyday. The following excerpts are from interviews conducted over a seven-year period by Andy Yale, who first traveled to Memphis in 1971 to meet Booker White. The photographs of Beale Street and its residents are selected from those Yale took during his stay.

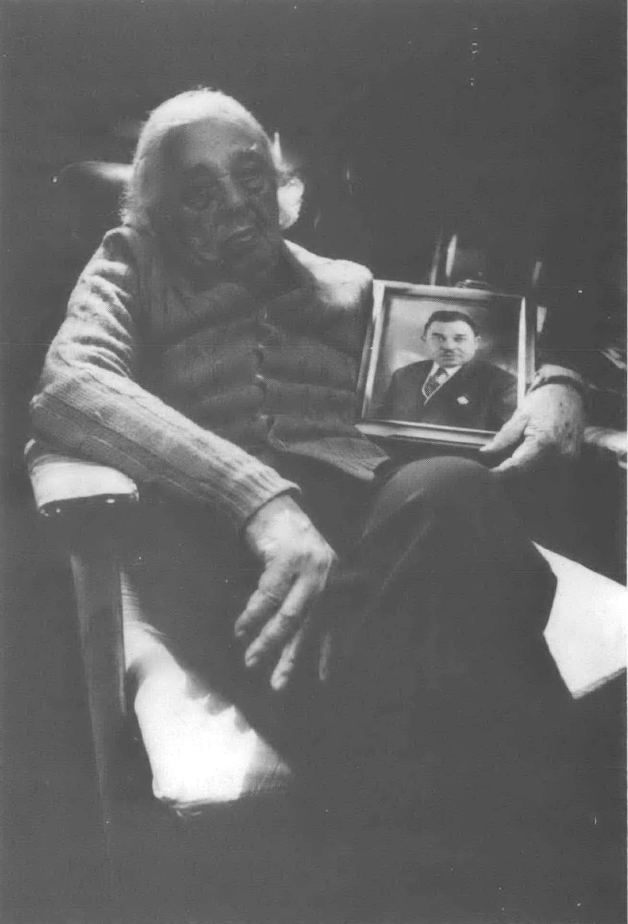

Furry Lewis

BLACK GYPSY BLUES

My woman must be a black gypsy, she knows everywhere I go,

She met me this morning with a brand new 44.

My woman got a mouth like a lighthouse in the sea,

Every time she smiles, she shines her light on me.

— Furry Lewis

Rabbit in a Thicket

Furry Lewis was born in 1894 in Greenwood, Mississippi, and came to Memphis with his mother when he was six. He grew up on Beale Street, and by the time he was fourteen, he was playing in W. C. Handy’s band. He was rediscovered in 1959 by Sam Charters, and toured widely. He has appeared in movies, on TV, and played with the Rolling Stones. Joni Mitchell wrote a song about him, “Furry Sings the Blues.”

Well, when I first started hanging around Beale Street, it was sixty some odd years ago. I’m eighty-three and been here in Memphis ever since I was six, because they brought me here from Greenwood, Mississippi, but I been around Beale Street all my life. That’s where I came up on.

Well, I first started playing down there, I was about fourteen or fifteen years old. I didn’t have a music teacher, nothing like that, but I go around people and see them play a guitar and I just watch their hands and come on back home and do the same thing. Then I joined Handy — W. C. Handy, that’s Christopher Handy — I started when I was fifteen years old. But I was a man that played with the band when one of the band people was off. But after that I got so good — I won’t say famous, now, but I’m famous now, though - I got so good until I got hired in W. C. Handy’s band.

I quit grade school and went to high school. And that was a school up on the hill - reason I call it high. Yeah. Then I hoboed and roustabout on the boats — I used to be on the Delta Queen all the time.

Yes, I hoboed. That’s the reason why 1 lose my left leg. That was in 1916. I have an artificial leg. I lose my leg in Dupont, Illinois, on the I. C. They take me to Carbondale, Illinois, to the I. C. Railroad hospital. And that’s where I stayed until my mother sent me some crutches. And then the railroad — they did send me back home - but I come mighty near going to the penitentiary cause I had no business hoboing. Had good money in my pocket at that time. I just want to save the money, just ride for free. But see what free get you — it don’t get you so much sometime, do it?

I worked for the city of Memphis forty-four years. I drive a mule and cart for the city when they didn’t have a truck. And then I pushed some little old buggies like you see pushing up and down the street, cleaning the street. I work on the city dump, you know, tell the truck drivers where to dump at, 1 work on the thresher where you wash the streets, and I nightwatched and everything. I was with the city forty-four years and they just retired me in 1966.

I can’t play the blues and live a Christian life cause I hope you heard this in your lifetime - you can’t serve God and the Devil, too. That settles that. You gotta let one of those people alone — let God alone and serve the Devil or let the Devil alone and be in prayer. You know prayer changes things. You know God above the Devil, but a whole lot of the time seem like people enjoy the Devil’s work better than they do God’s work. But they condemning their souls.

Yeah, blues ain’t nothing but the Devil’s work; you don’t hear no blues in no church. You never hear a preacher get up — a reverend or whatever name you want to call him - you never hear him get up and sing the blues. You heard him sing church songs. I know all church songs cause I study them. But if you study a thing and don’t do it, you lost. Yeah. I’m still with the Devil.

You want to come on down to the fact, I don’t call myself famous now. But I tell you what they do call me — they call me a rabbit in a thicket and it gonna take a good dog to catch me with a guitar. Every song that I sing I made it up myself. I never tried to pick up nobody else’s music. I always keep up that old tune like I always have played. Just like the church song say, “Give me that old-time religion cause it’s good enough for me.”

I’m a good bluesman but I play religious songs and I can pick a guitar. I pick near about anything anybody ask me. I can play some real good church songs and I mean play it. And I be singing and I ask my guitar to help me out and I won’t open my mouth and the guitar will sing the same song. I do that, I’m good on church.

Whole lot of people like the blues. Whole lot of Christians like to hear somebody pick a guitar and play the blues. And a whole lot of people don't like to hear it. But I can tell you this, there’s gonna be blues long as the world stands; somebody gonna play the blues. There’s gonna be blues, but a whole lot of people say they playing the blues and they be playing something else. I don’t try to follow behind them, learn them — the blues I play I been playing for many years. And I got my own style and I ain’t got a quarter now in my pocket. But I give anybody — if it ain’t too late I go to the bank and give anybody five hundred dollars — if they can beat me picking my style with the blues! I tell you that now.

I bet on Furry — and then people say don’t never praise yourself, but nobody else gonna do it quick enough. I’m a guitar picker from my heart! I am absolutely a guitar picker from my heart. I wants you to get Booker, I wants you to get any guitar picker what you know and bring ’em here and let ’em beat Furry. I run a ring around ’em. I just don’t know. You know me. Can I pick?

But I’m gonna quit picking guitar altogether and I want a younger head to pick up where I’m leaving off. I put the guitar down, I ain’t gonna play nothing, no. I let the guitar sit right there cause it cost me too much money for my guitar and my amp to just give to somebody. What I do, I take it out to the museum — art gallery — something like that, and have my name on it and everything. And just let it sit there until it rusts or busts or something. I’m really gonna quit, because I’m getting too old now to just keep this up. You need to get close to God sometime — you too. You can say this is old Furry Lewis.

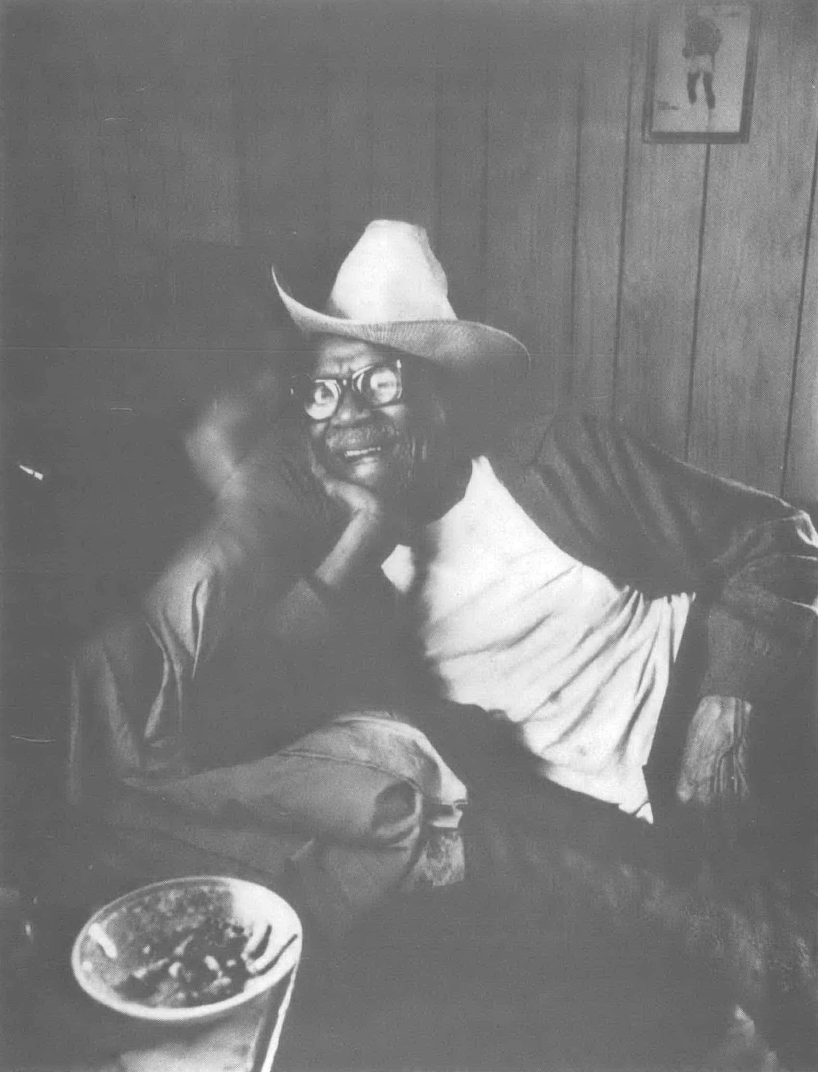

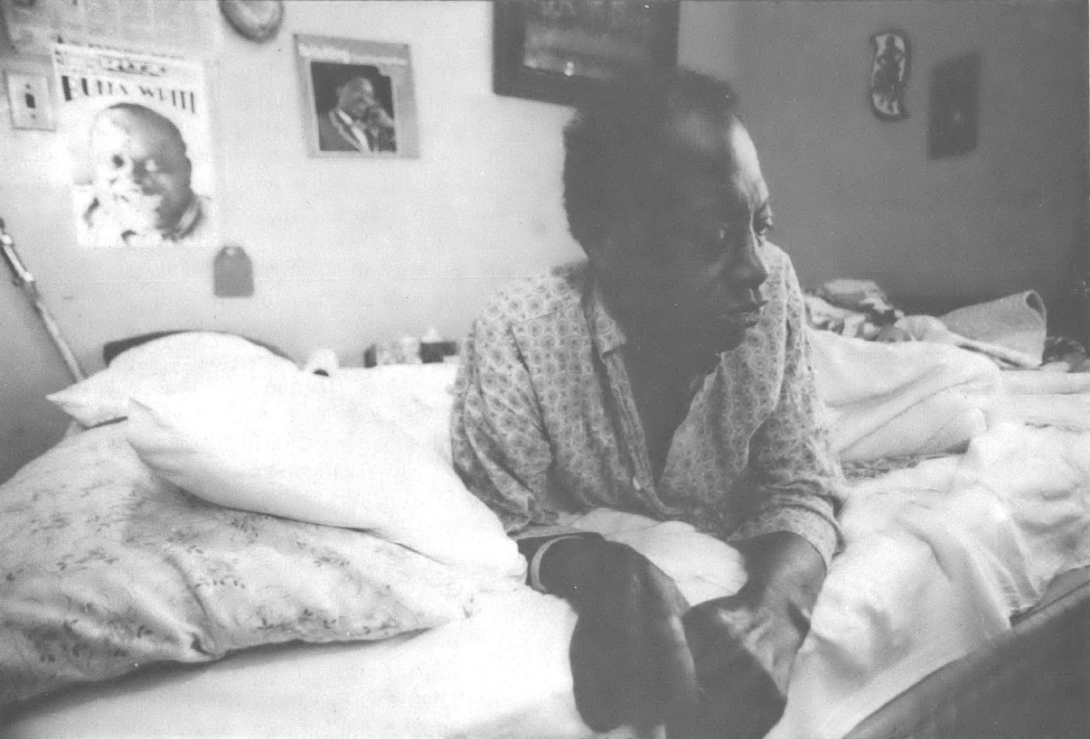

Booker White

The Smile of the Way

Booker (“Bukka”) White was born in 1909 in Houston, Mississippi, and died February 26, 1977, in Memphis. One of the great Delta bluesmen, Booker White played in a driving, original bottleneck style, and recorded in the 1930s and ’40s for Okeh and Vocalion records. He hoboed and traveled all over the South and Midwest. During the blues revival of the mid ’60s, he was rediscovered by John Fahey, and toured extensively. Besides his original recordings, Booker is also on Takoma, Arhoolie, Blue Thumb, Biograph and World Pacific labels. Columbia reissued many of his original recordings on an LP in the late ’60s.

A lot of people let money run em crazy. They be as poor as crawfish and they get some money, they change. I ain’t never been like that. I always been nice to people, knew how to meet people, if I could help em, I help em. And I been a success behind that. Yeah, I’d help somebody else that trying to go along. You see, that’s so many people’s trouble. They wants it all to themself and don’t try to help nobody else. But I tries to help people as I go along. You can’t live in this world by yourself. Rich or poor. That’s what I like about the good Lord, he don’t care no more about the rich than he do the poor. Cause he made us all.

We play for white and colored, me, my daddy and my sister. We kept pretty busy all the time, wasn’t no problem. Charlie Grice, he was a harp blower, he stayed busy. Luke Smith, he stayed busy. All back there, them old people right, I’m telling you. B. B. (King)’s grandfather, he was the king of all of them. Name Jap Pullian. That’s his grandfather. You couldn’t hardly stand to hear him play. Man, that man could play. Well, at that time I wasn’t going out. I’d be at home when Uncle Jap and them would come over there. I had an auntie, she played pretty good. But my sister was a king, man. She sing so till frogs and things hop up and listen at her. Yeah, they’d hop up and listen at her. She could go, I’m telling you the truth. But after she married we got rid of her. We wouldn’t, you know, try to take her off nowhere. So she passed, and her husband, he dead. Me and my father taken it over.

See, Papa died in ’38. That was a fiddle man from his heart. I never played with a guy could play anything in open G, he play all kinds of tunings. I don’t care what you play, he go along with you. Yeah, he was good. No problem for him to do those kind of things. So from a little boy nine years old, I come along to be an old blues player.

So many nights I would play. 1 wouldn’t have but two or three strings on my guitar — be done broke the others. But they couldn’t tell the difference. It sound good, they dance by it, and they just had a nice time. It never did throw me back — I break all my strings, down to one and two and I still be playing my guitar.

You know sometime you can be playing music and you can make a song so sad you can’t take it. I have been to places and the house man would come and tell me, now Booker, don’t play that no more — it’s upsetting too many people. And I came to find out he was telling the truth. A lot of times I be playing, I have to stop, I can’t take it. So many time. A lot of people don’t understand that. A Christian feeling and the blues — both of em will make you shout. But the blues has got more power to it than a church song. I got a lot of songs, spiritual songs. I got just as many spiritual songs as I got the blues in a way. But there’s so many people ain’t got the spirit — they got the blues, that’s what they want. They want the blues, their whiskey and wine they drink, then they feel like they can walk to heaven without dying.

I be lying here like I’m sleeping and I be having a song on my mind, turning just like the tape reel. Some of them I have to quit, cause they just make me sick. I be feeling so good even over things that I used to do. Past life. I don’t know what tomorrow gonna bring — that’s the best I can get out of life, thinking about what I done did. I can have for the future what I want to do, but I haven’t did it, and may not be here to do it. But the past — I done did that. That give me something to think about, give me something to talk about, give me something to play. There’s just something on the line moving all the time.

When you get up there and go to playing, hit that stage with that right stuff, it’s going to come out all right. That’s what I told B.B. when we went to Peoria, Illinois, going on three years ago. Well, I meant that cause I know Willie Dixon, Muddy Water. I know all them could play. But I had such a good feeling on me, I believed I could put it on them. I said, now I’m gonna tell ya’ll, when you hit that stage if you don’t play right, it’s gonna catch afire on you. And they said, alright, White, we’ll do that. I said, I ain’t gonna try to play to beat you, I’m just gonna try to play to make you feel good.

And when I hit that stage, I jumped on that stage from the depths of my heart with all kinds of feeling. And I never knowed in all my playing, the people to tote me off the stage. They tote me off that stage. I was in such a high gear and feeling so good, till they come up there and toted me off that stage. And I had them boys so, till I’m telling you, they didn’t know what to think. Muddy Waters and Old Willie Dixon — he said, well you done did it again. I said, I’m gonna do it all the time when I feel good. He said, Booker, you played tonight.

See now, where people make such a bad mistake — young folks die like old folks. You go to the cemetery, you see many short grave as you do long grave. No, it ain’t like that — cause you young, that doesn’t stop death, you still die. But we hoping we don’t die till we get to the point of the time. When we get there, we gonna die, we born to die. But while we living, we gonna try to make it a great life. And when you make it a great life and a happy life, when you die, you most have a smile. Cause you done went, the smile of the way. So, so long to all of you, I hope when I get up, I can meet ya’ll and tell it better.

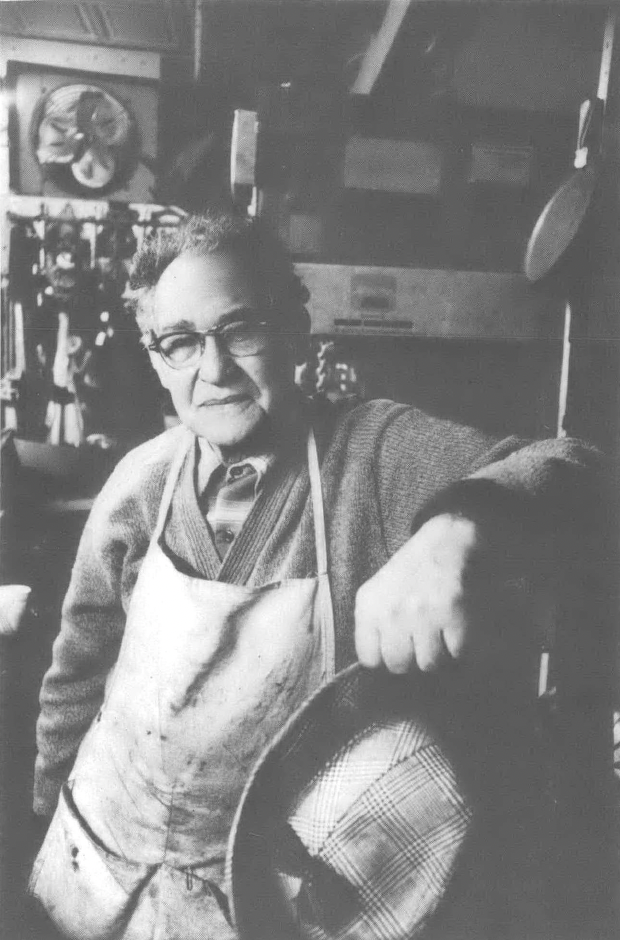

Art Hutkins

And We Did Do Business

Art Hutkins runs a hardware store on Beale Street, one of the last four stores still open. He has been on and around Beale since he was a kid, starting out as a pawnbroker’s clerk and watchmaker.

I come down here in ’35.1 worked up on the next block in a pawnshop. I was a watchmaker and clerk. In the store where I worked, we took in mostly watches and jewelry. Now, in those days the pawnshops down here took in mostly clothing. Clothing and jewelry and things like that. But the pawnshop I worked in, my boss didn’t like clothing; he liked jewelry. We used to take in diamonds and watches and things of that sort. Outboard motors, musical instruments, all that kind of stuff.

Morris Lippman was one of the old-time pawnshop operators. His daddy was an old-time pawnbroker with his mother. And after they died he took the store over and he operated under the name of Morris Lippman until he sold out to Willy Epstein.

I drifted into the hardware business. I opened up a store over at 156 Beale and that was in 1941, the same year I got married. And I opened up the store, it consisted of dry goods, jewelry and things of that sort. And all my customers came there looking for hardware. So I investigated and found out that location was a hardware store for years and years before I moved in and everybody came there looking for hardware. So I just changed to the requests of the customers, that’s all. They wanted saws, I could put em in saws. And I dropped the jewelry and dropped the clothing. So that’s how I got into the hardware business.

The fun part of Beale Street, that was mostly the other side of Hernando. They had clubs down there, had dancing and singing, nightclubs, and all that kind of stuff. Like any other city. It was just a little city but mostly black people were down here. Then they had the pawnshops and everything. They had dry goods stores and they had restaurants, they had shoe stores, they had second-hand furniture stores, bakery, all kinds of stores like that. Just like any other neighborhood. Takes all kinds of stores to make a neighborhood. It was all strictly a business street, strictly a business street.

But, hell, it dates back to an old-time street. You take years ago, the boats used to stop down at the foot of Beale Street and all the help down there used to come up to Beale Street and do their shopping. Come up here and buy clothes and buy everything, go to the show, get a good drink, get a bottle of whiskey and all that kind of stuff. In those days people didn’t worry about a pint of whiskey, half pint of whiskey — they bought a quantity of it. Gallon. Sure, whiskey was cheap in them days. This was a whiskey store, oh, long time ago. In the basement they keep barrels of whiskey — ten-year-old whiskey, eight-year-old whiskey, and you know, different kinds of whiskey — and they used to go down there, take and buy you a gallon of whiskey, and seal it up for you. Years ago country man came in and bought one hundred pounds of coffee, one hundred pounds of sugar, big cans of lard, and all that kind of stuff. And they’d do that here on Beale Street. It was noted for that. Everybody came here — boats, cotton, everybody used to come here.

You see behind all these big buildings — an ark is like a row of houses and you have people live downstairs and people live upstairs — we used to call them an ark years ago, and it was one ark after another, you know. I guess at one time we lost ten thousand people living in this area. Years ago everybody lived behind these buildings, everything. And all those people came down on Beale to do their shopping over here. We used to have two hardware stores here, had one about three blocks from here. And we always did business.

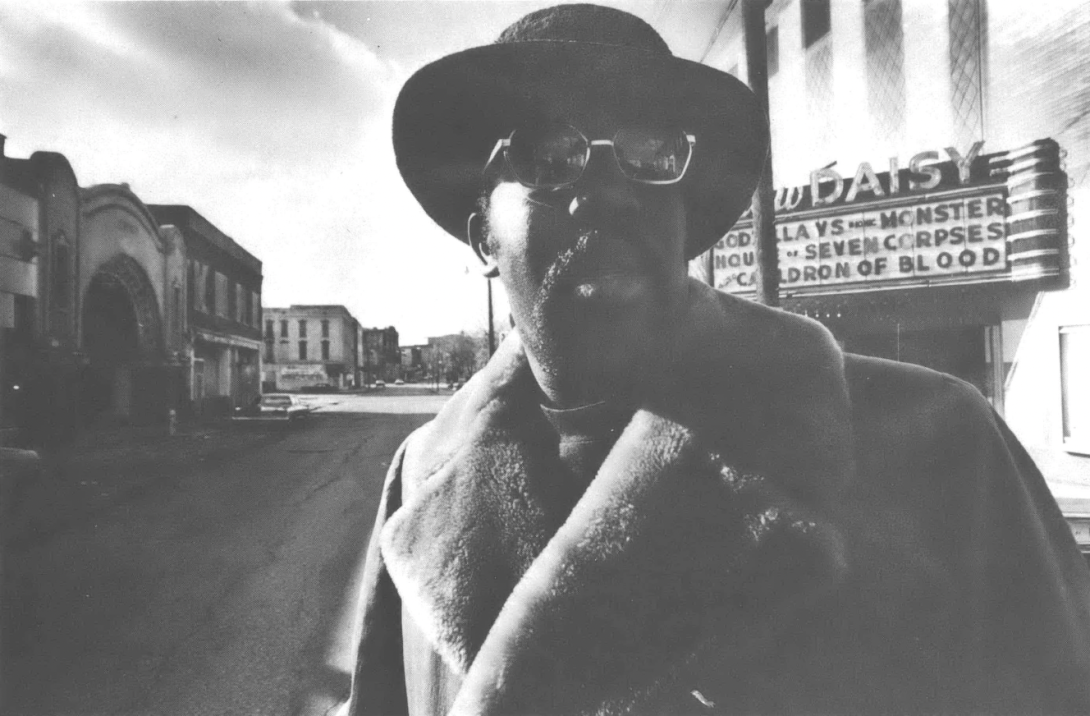

Casey Banks

A Real Live Scene

Casey Banks is a free-lance promotions man, musician, and pool player who grew up on Beale Street. His memories of Beale and its people generally relate to his childhood. His generation was the last to grow up on Beale.

Well, I think when I was real small, maybe at the age of eight or nine years old, you know, the only picture show that black kids could go to was on Beale. Like they had some other picture shows up on Main Street but you had to go in the side door. It was a segregated situation. And these movie houses were primarily for black people, you know. They didn’t have what they call black-oriented films; they were the same films that you’d see in the white theatres but maybe they had played in white theatres four or five months before they got to a black neighborhood.

And Beale Street was rather an exciting place, especially from the eyes of a kid. You got to see a lot of things — man, you know, it kind of reminds me of the pictures I’ve seen of the Roaring Twenties. You know, ladies all made all up and heavily made-up lips and big earrings and they strutting and dancing. People used to really fix themselves up, wearing the zoot suits with the big chains and the long pointed shoes and the big Stetson hats. And the girls used to wear their little fake mink coats and the funny-looking dresses — real flimsy-looking dresses, and the beads hanging all the way down here — man, you know it was a real picturesque scene. It was a fashion show constantly. On Easter and Christmas, Christmas Eve and Easter, New Year’s Eve — man, everybody dresses up, more so than they did on Fridays and Saturdays. Everybody put on their Sunday finery and go down on Beale and just hang around and look around, you know. That was the thing — just show out on Beale Street. If you got a new car, man, if a cat got a new car, first place he came was to drive up and down Beale and show off to the fellas. Hey, look at my new car.

I used to sell Jet — that’s the little black publication and magazine — and I also sold Tri-State Defender. So we used to go into these cafes to sell our merchandise to the patrons. And we got a chance to see all kinds of things, man, you know. But as a whole, the whole thing was just a fun scene. Man, it was crowded, like every night of the week there was a big crowd down there, and in the morning when the joints open up, they were crowded, and all day long it was crowded.

During certain days of the week — on Wednesdays and sometimes on Fridays — there was a theatre called the Palace Theatre and they used to have amateur hours down there. And the amateur hour consists of whoever want to be on the amateur hour — you come by and come to the side door, which was back around in the alley, and you knock on the door, and tell them you want to be on the show. Well, they had a little auditioning stuff, which consist of one guy who made up his mind whether or not you were talent-worthy. He have you sing four bars of something and then — “Okay, you can go on; can you keep time?” No uniforms or nothing. And the place was packed. They had a big band there — Phineas Newman band. If you ever heard of Phineas Newman, his son, Phineas Newman, Jr., he’s a world renowned pianist. And the Phineas Newman that I have reference to is his father.

They went on, and they ventured a little further outside of just the amateur hour; they tried to revive the ear of burlesque down on Beale. They used to have a thing down there called the “Brown Skin Follies.” And we were too young to be in there, so we used to hide up under the seats until they put out all the kids, you know. When the show started, it was easy for us little bitty cats to hide somewhere, you know, you can’t see us. We used to sit there and watch the shake dances and whatever. It was a real live trip down there.

They also used to have big band shows. You know, they brought in Tuff Greene, Bobby Bland, B.B. King, oh man, everybody that you ever thought you wanted to see was there. I remember the first time I ever saw Bobby Bland — I saw him in a sideshow in Church’s Park and that’s on Beale. Bobby Bland was singing in a little, you know, little tent-type show. And who was to think he was ever to become a big star? And B.B. King was doing the same thing. All these cats, man. Club Handy was another major attraction, a place where major black attractions came to. And quite a few white people used to come down there cause this was the real Beale Street. Beale Street started at Third Street and it went from Third back to Fourth Street — it was just that one little strip. Now maybe forty years ago it may have stretched a little further, but the era I know about it started at Third and stretched on back to Fourth Street. And that was Beale. Hernando Street was another part of Beale Street.

The old-timers kind of ran things down there, you know. They monopolized the situation. Like if you were in good with the old timers, shit, you had it made. But if you weren’t in good with the old-timers, well, you know, you just had to be on the outside, peeping through the door.

See Memphis is a hub, you know, to Mississippi, Arkansas and certain parts of Tennessee. When people call themselves coming to town, say the people who stay in Arkansas and north Mississippi, this is where the black people came to have a good time. And some of them, they were migrant workers and things, and they saved their money for two, three, four, five months just to come up and have a big blast on Beale, you know.

And there was quite a few little soul food joints down there. Miss Culpepper had a rib shack around the comer — she a big church lady, she didn’t stay on Beale none. And she never would say no to anybody. If a cat was hungry, you know, go in there and Miss Culpepper she going to feed you. And it was certain other places if you were a regular customer. Nootie’s, she was a madam, she was around on Hernando. She had a little prostitution joint around there, you know. And Nootie would feed you. And you eat all you want there; they had cooks and things, good food. Man, you know, people exhibit a hell of a lot more love and understanding and compassion during that era than they do now. It wasn’t so much of a doggish situation. Very seldom you hear about somebody getting ripped off or mugged. Well, you know, a little mugging went on, but it wasn’t as bad as it is now. No kind of way.

Because they had some real live head-cracking police down there, black police you know, and they wouldn’t hesitate to busting your brains out in any kind of situation they got you into. And they ruled Beale Street with the strong hand of the law. One of the most significant ones was a cat by the name of Shug Jones. And he was a black dude — cat couldn’t read and write — used to be a janitor in the police department. And when they first started hiring black cops they made him a police. He was the terror of Beale Street, him and another cat named Jubal, and they ruled Beale with an iron hand. Like you just didn’t get away with that shit there, man. No kind of way. They were very much on the job. Because (Mayor) Crump ran things, you know. Crump was what you call a dictator. He ruled Memphis with a strong hand. Black people had their place. Their place was Beale Street. The black cops were striving for equality under the same administration of the law. And they were trying their damnedest at being as proficient at administering the laws as white cops were. It’s just the difference was they couldn’t arrest any white people. They couldn’t go any further than a black neighborhood. It was two different cities, one black and one white. And Beale Street was the black folks’ downtown.

But white people came down on Beale. You know you had a lot of liberal whites that used to come down and frequent the Beale Street area. And what was so wierd about the whole situation was the white people that came down there, they had a good time and they got right involved in whatever was going on and it was no hassle. There may have been a little resentment, but due to the circumstances of how black people were persecuted for being black folks, they had to accept the white people for what they were, and be courteous and nice to them, even though you wanted to bust some of them in the head. But you weren’t in a position to do that. Know what I mean? So they came down, they freely enjoyed the company of black ladies, spent a lot of money drinking and shit, and had a good time.

Pawnbrokers enjoyed kind of a, well, a pretty good relationship with the black people down there, cause of the fact of the economic situation. Black people didn’t have much money, and pawnbrokers would kind of have one eye closed to certain things that you used to bring to pawn, hot or whatever. If you happened to be all right with this particular pawnbroker, you could pawn anything. They had the money. When you got the almighty buck down there, you a welcome addition to the system. And they controlled quite a bit of money down there, so they were readily accepted.

That was the part of Beale Street they call the slum area, you know. Way up across from the pawnshops. They sold a lot of notions and potions and good luck charms. That’s how they stayed in business, selling a lot of shit that’s gonna make you have good luck. And you know how superstitious our black folks was, they flocked up in there buying all that crazy shit. Some magic, super good luck powder — throw it on the floor, throw another pinch over your shoulder, you supposed to have good luck. Old people just so foolish, they bought it.

Elvis Presley used to stay up on Linden, on Linden right across from Lee School. You know, he stayed in a black neighborhood. And he had an old motorcycle, and he used to ride around on his old motorcycle. And he had a guitar, and he used to sit on the porch — real live, what you call country yokel. He sit on the porch over there on Linden, he sit over there and play his old guitar — he was mostly a country and western dude, you know. He always used to hang around Church’s Park when cats was rehearsing and singing and things. He used to come and play his little guitar and listen. He loved black music. His emergence as a star came mostly because of his association around black musicians and his interpretations of how it’s supposed to sound.

Robert Henry was the kingpin down there, he ran things, you know. When Elvis was looking for a place to start somewhere, he confronted Robert Henry to give him a helping hand. And Robert Henry, at that particular time, didn’t know nothing about managing no white boy. Robert Henry turned him over to Sun (Records), let Sam Phillips deal with him. And Sam Phillips, in turn, most of his artists were black. White stations wouldn’t even play his songs cause they say it sound too black. Well, this is where he came from, and this is the kind of music he was accustomed to, so he couldn’t do any better than to be sort of a white black entertainer.

He never forget where he started his shit from. When he first started getting big, like he’d come down to Lansky Brothers and walk up and down Beale Street, and fool around down there, hang around down there, get his picture took, you know. People had a whole lot of affection for him simply because of the type of character he had. He was a milk drinker; he’s a, excuse the expression, he’s a habitual cocaine snorter, but very few people know about that, you know. But they projected an image of him as being a sweet milk drinker, donut eater, Mister Goodfellow, you know.

Beale Street, you know, like they tried their damnedest to revive it, then they came up with this urban renewal situation. Some of the buildings is kind of condemned and things. They give them an opportunity to renovate them, to try to upgrade them — that’s how Robert Henry came into that pool hall over there. They renovated one section of Beale Street. But the other section, the Palace Theatre, there was a long controversy about tearing it down, because it has meant so much. It had launched careers, you know. Just think, that’s where B. B. King came from, that’s where Little Milton came from, that’s where Bobby Bland came from, that’s where Muddy Waters came from. All these cats started right down there, man. There was another cat named Bilbo Brown. And he had a little traveling troupe called Bilbo’s Brown Skin Follies. Man, that was a real live show to see. It was Las Vegas style on the black side. All this went on at the Palace Theatre. And when they tore the Palace down, ah, well, things just started to decay.

When the new generation ’50s children — kids born in the ’50s and early ’60s — when they started growing up, well, hey, their legacy from Beale Street is practically nonexistent. I would love to see it revived, but I doubt very seriously — because you got to capture that magic. There was kind of a magical situation down there. And, man, was it beautiful. It’s hard to explain, it’s just one of those things.

Right around when the Civil Rights Acts was passed, black people started going to other shows and they scattered around and stopped really patronizing, you know, their roots where they came from. That had a whole lot to do with the downfall of Beale. Because it would have been very easy, it would have been just as economically feasible for them to renovate the buildings as to tear it down. It cost a whole lot of money to tear down a building. So they tore down those buildings, they could have just leave them and refix them. But some Harvard brainchild thought up he’s gonna make it a blue light district, then it’s gonna be a red light district and then they done had a thousand different propositions and plans about what it’s supposed to be and what they’re gonna make out of it. And none of it came true. And from the way it looks, it’s gonna be in the planning stage for the next five or ten years before they do anything down there.

They been squabbling about it now ever since they tore the buildings down. And this has been four years now. The Federal Government allowed them some money and they bought the joints out. And they relocated all the people, gave em severance allowance and things. When the federal government stepped in and did their thing, there wasn’t shit to be said about it. What you gonna do about it, you know? You got to sit back and accept it, because that’s what time it was. Uncle Sam, they declared Beale Street a shrine, wasn’t nothing to be done about it, just keep it as a shrine.

Tags

Andrew Yale

Andrew Yale is a free-lance writer and photographer living in New York. (1982)