This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

People in Memphis were excited when, in early 1966, the Radio Corporation of America moved its color television production there from Indiana. Political and business leaders rejoiced at the prospects that new jobs, increased taxes and booming sales for local suppliers would help Memphis' economy. Workers looked forward to union wages, and many black and women laborers saw a long-promised opportunity for skilled and semiskilled jobs.

Five years later, the new plant was closed; its production had apparently been moved to Taiwan. In rapid succession, 4,000 workers had been lifted from a basically non-industrial lifestyle to assembly line jobs with union protection and then cast aside in favor of cheaper labor in a Third World country. Where poverty had been, RCA brought prosperity; yet when the dynamics of the capitalist economy commanded, RCA left and poverty returned.

The people of Memphis, concerned about these rapid changes, began to blame each other for the loss. Public opinion turned against the RCA workers, who were variously described as uncooperative, inefficient, greedy and — with their "aggressive” union — too demanding on the company. But the city was caught in more than a simple Management vs. Worker conflict. A complex set of cultural and economic forces were involved which few understood, forces far beyond the control of their principal victims — the plant's workers and their union.

For most of this century, the South in general has suffered from an imbalance in the distribution of the nation's industry. The core of America's economy is dominated by large multinational corporations — auto, oil, rubber, steel, etc. — owning most of the wealth, producing the largest share of profitable goods and services, and paying the highest wages. On the other hand, the secondary economy is populated by poorly managed companies, neglected by the government and subjected to intense competition. The workers who staff this sector face low wages, low productivity and unstable employment. Since the region is overrepresented by secondary industries — textiles, apparel, food, furniture, etc.— Southern workers have had little option but to remain in secondary jobs.

Generations of progressive Southerners have attempted to alter this situation by attracting larger and larger corporations to the region with liberal tax breaks, free services and public subsidies. For the most part, however, they have only succeeded in attracting those corporations which are most subject to severe product competition. From textiles in the 1920s to electronics in the 1960s, the large corporations have moved South and offered new opportunities to the region's workforce at precisely the point when the South provided distinct economic advantages to the companies. If those advantages are eroded (e.g., by increased labor costs or decreased consumer demand), the runaway shop in the South may look for a new site for its production — this time outside the nation's borders.

The story of the RCA plant in Memphis illustrates this problem. Largely because of rapid fluctuations in the domestic consumer demand and the international supply of televisions, the movement of RCA's production from Indiana to Tennessee to Taiwan was telescoped into five short years. Secondary workers in Memphis were hired, trained, made productive, and then replaced with cheaper labor abroad. The long-term benefits to the city of a multi-million dollar employer-taxpayer- consumer suddenly disappeared. In the end, Memphis had no control over RCA's commitment to the region or its people. When the company decided it was more economical to abandon a $20 million facility and move overseas, no one could stop them. It was just one of the possiblities the people of Memphis had to accept when they became involved with a multinational corporation.

Promised Prosperity

Historically, Memphis developed as a commercial and banking center for the highly productive agricultural region of the Mississippi Delta. Over the years, vast quantities of cotton, soybean and hardwood lumber, the major products of the region, were shipped from Memphis to national markets. Service industries, headed by a large regional medical complex and an extensive warehousing business, provided employment for a large unskilled and non-unionized working class.

The post-World War II economic miracle offered few benefits for Memphis. In fact, the city suffered a series of economic setbacks. The Ford Motor Company, employing several hundred people, moved its assembly plant elsewhere. Faced with intense competition from carpets and plastics, one of the city's strongest industries, hardwood and cabinets, slowly disappeared. And the local wholesale grocery industry, made obsolete by the rising supermarket corporations, became a shadow of its former self.

By the late 1950s, manufacturing facilities in Memphis were clearly limited. Local banking and real estate interests dominated the city and regional leadership, and the social class structure was a near duplicate of the Delta's rural counties. Members of land-owning families invested their surplus capital in Memphis commercial and banking enterprises, while the untrained and poorly educated sons and daughters of sharecroppers and tenant farmers immigrated to provide an inexhaustible surplus of manpower. Opportunity for inter-class mobility was limited as urban businesses continued a tradition of paternalism in owner-worker relations.

The arrival of RCA, a multinational conglomerate, promised a dramatic change. While known for its electronic products, especially TVs, radios and phonographs, the company also produces space and military equipment, carpets, frozen foods, furnitures and books. In addition, it owns several broadcasting stations and NBC, the radio-TV network.

Following the 1960-61 recession, RCA's profits grew rapidly, reaching a peak of 19.11 percent on net worth in 1966 (twice the level it would achieve in 1970). Net income rose from $35.1 million in 1960 on sales of $1.5 billion to $132.4 million in 1966 on sales of $2.5 billion. Much of this growth was due to the phenomenal demand for color televisions during the first half of the 1960s. RCA, the primary US developer of color and dominant seller of American television sets, commanded the lion's share of the new market. By 1965, the company had also established plants in Chile, Mexico and Taiwan to compete in the low-priced portable black and white television market.1

In late 1965, RCA announced plans to build a modern, highly-efficient plant in Memphis to replace its aging color facilities in Bloomington, Indiana, and to assemble black and white sets until the foreign plants reached full production. The move promised advantages to both RCA and the people of Memphis — for completely different reasons. RCA gained the convenience of a major transportation center, access to cheaper labor and many of the benefits — sewage treatment, service roads, etc. — offered by Southern development commissions. On the other hand, the Chamber of Commerce said, "Completion of the Radio Corporation of America's plant here will give Memphis a $27-million retail sales boost." According to the chamber, some 50 companies expressed an interest in supplying parts to the new factory.

Memphis workers were also excited by the new employer's arrival. The $2.25 per hour offered by RCA for line operatives bettered by at least 30 cents that paid by most non-union shops in the city. Women who came out of domestic service could improve their wages by more than a dollar an hour, and the company announced that its workforce would be well over half women. Black workers, who had been traditionally denied mainstream jobs, were also enthusiastic about RCA's well-publicized non-discriminatory screening and hiring practices. In addition, the company said it intended to let one of two unions (either the International Union of Electrical Workers or the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers) represent all wage-employees, thus guaranteeing a package of benefits which few workers in Memphis enjoyed. (Only 23 percent of the city's workforce is unionized.) In short, RCA offered thousands of workers, especially blacks and women, an opportunity to move from secondary jobs, characterized by unstable production patterns, arbitrary work rules and few benefits, to a primary labor market. By February 6, 1966, only six weeks after the company's move became public, the head of the Tennessee Department of Employment Security could predict that RCA would have over 15,000 applications from which to choose its workforce.

"When I hired on at RCA," one woman recalled, "it looked like it was straight from heaven. It was more money than I'd ever seen. The plant was even air-conditioned. And the best thing, it was the first time me and the family had ever had any hospitalization. I thought the world had finally opened for us."

"It was a 50-mile drive each day for me and another couple," said a worker from one of the surrounding counties. "Getting up so early was really hard, but the money was worth it. There ain't no work in this county. When I got the job I went over to my old boss and told him I didn't have to do all the part-time jobs for him no more.''2

By June, 1966, one thousand employees had started plant production. An additional 2,800 workers were hired by the end of the year, bringing total employment to just 200 below its peak level. To fill its need for foremen and line supervisors, RCA raided other local plants for experienced personnel and opened the lowerlevel management positions to women and blacks. But like the operatives, these supervisors had no actual experience on the type of modern assembly line developed for the new plant. Even the foremen, who were mostly white men, were largely unfamiliar with such an operation. Key management personnel were transferred in from other RCA installations, and the skilled electronic technicians who repaired defective sets were recruited regionally, from South Carolina to Texas.

First Problems

The first year of the plant's operation was a study in contrasts. The Memphis Commerical-Appeal boasted, "With 3,700 workers, the RCA plant now stands as Mid-South industry's biggest single employer, and still more will be employed in 1967 as the company expands the plant to produce more than one million television sets annually."3 But community pride at having attracted so large a corporation was tempered by the sudden awareness that the plant afforded the local black community a source of financial stability and independence far beyond anything previously available. Apprehension increased when the company recognized IUE as the bargaining agent for its employees, making the plant the largest union shop in the area. Meanwhile RCA workers, women in particular, developed an intense dislike for RCA's distant and authoritarian production methods, even though they found the jobs provided an opportunity for upward mobility.

By early 1967, economic problems forced a change in working conditions. The market for color television did not grow as expected during the second half of the 1960s. Sales failed to increase in 1967, remaining stable at about $2 billion for their industry. And the demand for black and white sets actually began to fall. In addition, RCA paid the price of being first. Competitors such as Zenith and Magnavox began to eat into RCA sales with higher quality, more reliable televisions. Foreign producers, like Sony, entered the market with cheaper, more compact and easily portable models. American companies, in a move to cut costs, began to transfer portions of their television production to Mexico and Taiwan, taking advantage of those countries' semi-skilled, low wage,under-employed labor force.

In March, 1967, after less than a year of operation, RCA announced it was placing 350-400 workers at the Memphis plant on furlough. Although the layoff was eventually postponed, it signaled the growing impact of low-priced, foreign made sets on US production.

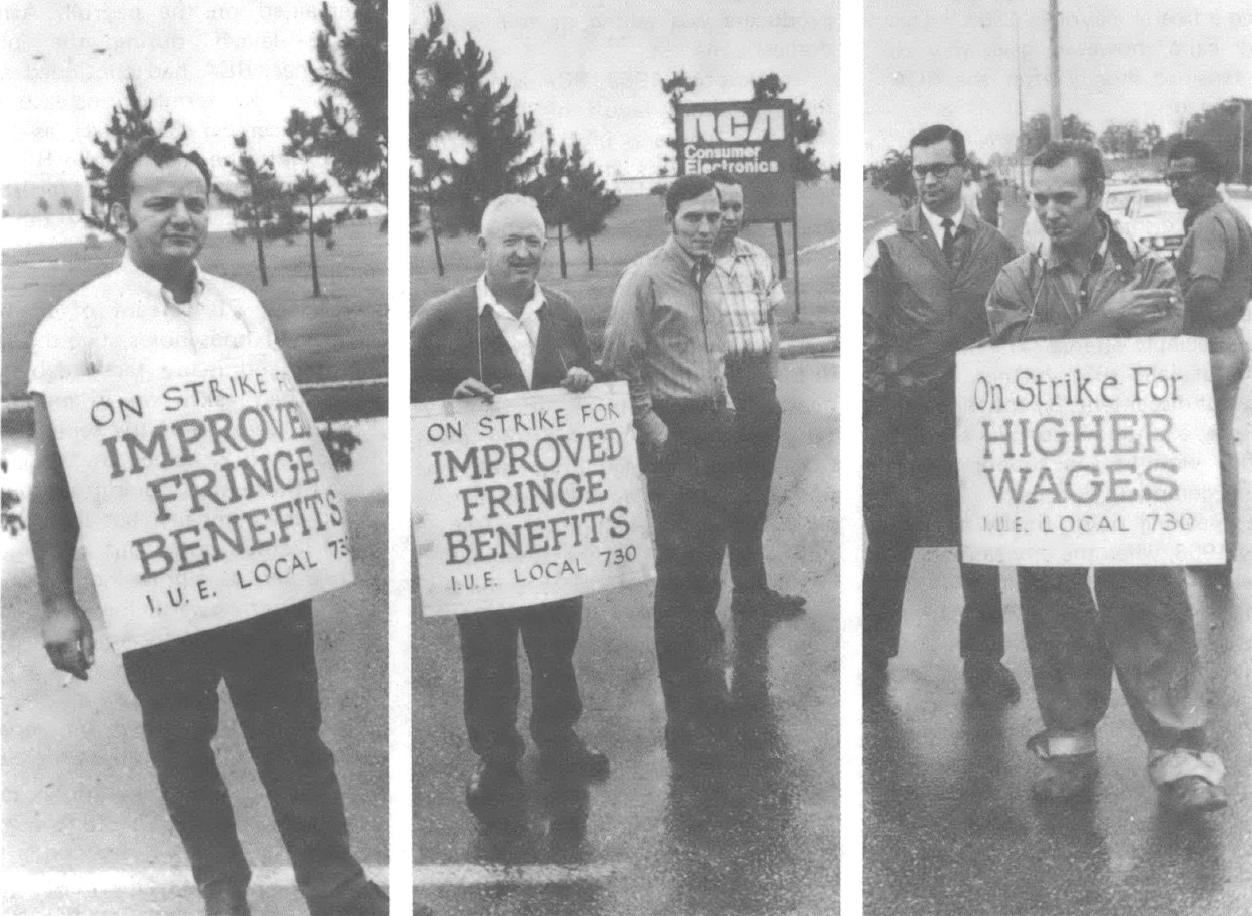

Internal labor dissatisfaction with conditions at RCA's new facility was also steadily growing. On Thursday, March 10, 1967, a minority of workers walked off the job and set up a picket line outside the plant. By early evening, all production came to a halt. One shop steward explained the complaints: "The production rate has been set so high we can't keep up. They've had a time-study man in here but they stall on negotiating grievances. On and off, they've made us sign up even to go to the restroom."

The union leadership, while sympathetic to the wildcat, officially opposed the walkout. After several arrests and much bitter debate, the strikers agreed to return to work on Monday. The union and the company agreed to name a special committee to work on a list of grievances, including the two chief issues behind the walkout: the production speed-up and the restriction of bathroom rights. But job control issues continued to plague the plant, causing a huge backlog of grievances to build up over the next two years.

On June 6, 1967, the IBEW struck several RCA plants in the US over wage increase and cost-of-living issues. In Memphis, the IUE continued its negotiations with RCA without going out on strike; however, a week later, the plant was shut down due to a shortage of parts from the IBEW plants. One week into the Memphis layoff, the IUE signed a new contract with RCA, but the IBEW continued its strike until early July.

Finally, in August, the plant turned out its millionth television set, marking a production rate of nearly 125,000 sets a month, one-third in color, the rest in black and white. The Memphis RCA plant had reached its production zenith.

Workers Complaints

From the beginning, the production schedules made by the national corporate office were unrealistic given the profile of the Memphis workforce. Most employees, lacking the skills required for television assembly, attended brief training sessions at the outset of employment. But this training did not prepare them for the mechanized rigors of modern assembly line production. Many workers had no previous industrial work experience, and those who did were used to the relatively undemanding and paternalistic work of secondary employment. In general, workers were accustomed to irregular work habits and considerable social interaction among employees. Many lived in rural areas and commuted to the plant daily.

RCA, on the other hand, demanded a tightly-disciplined workforce. It set up the assembly line for a rapid, mass production system, planning for only a small profit per set produced. Line stoppage or personal interaction could not be tolerated. As one former management official said, "Our policy was to get what it wants at all costs."

This company policy proved to be difficult, even shocking for most of the new workers. One commented, "I think of a job as a place to meet people, make good friends. In the place I worked before RCA, all the girls were always bringing in food they had cooked to share. There was always a lot of kidding going on. We would double up on our jobs so we could have more breaks and have time to talk.

"RCA had none of that. That line was so fast I could hardly do my own job. It seemed like I was always sitting in the lap of the woman next to me just trying to finish a set before another was coming at me. We got 12-minute breaks in the morning and afternoon but it took you five minutes to walk upstairs to the bathroom. I was there two years and never got to know anybody. It was tedious work. All we had to do was sit there with a pair of pliers and crimp terminals all day long."

Another woman stated, "I quit a job at sewing seat covers. Everybody was really nice there, even the boss. When I got to RCA and was put on the line, I wanted my old job back, even for less pay. The line was just too fast. The foremen really thought they were somebody. They'd come from plants and they didn't know anymore about the work than we did. I yelled at my foreman a lot. The plant manager would walk through the plant and never speak to anybody.

"I quit after nine months and worked in a grocery store. It didn't pay as much, but I had more freedom." Worker dissatisfaction showed up in high absenteeism and sloppy work performance. On some Mondays, so few people showed up for work that it was necessary to shut down entire lines. Salaried staff frequently had to fill in. Even giving workers S&H Green Stamps as an incentive for regular attendance didn't solve the problem.

Many sets came off the line defective and had to go through expensive repairs before they could be shipped out. Some workers said that they deliberately skipped units just to keep up with the speed of the line. Others damaged terminals completed by fellow workers just to hurry their own task. Conflicting reports indicate that at any one time from 20,000 to 40,000 defective sets needed reworking by highly-paid electronic technicians.

The speed of the line contributed to the constant tensions between operatives and first-line management. Frequently inexperienced foremen would not (perhaps could not) make the necessary decisions of when to discipline workers. As a result, problems which could have been resolved on the line were submitted to arbitration through the lengthy grievance procedure. "There was such a backlog of grievances," one shop steward noted, "that we were just a half step from a strike all the time."

Not surprisingly, RCA workers gained a negative image in the traditionally conservative Memphis business community. Stories circulated widely that the operatives did not possess the skills to perform even the simplest of tasks, that they used abusive language toward foremen, and that "the union had spoiled" them. Actually, local businessmen were bitter that RCA had increased wage rates in the area.

By 1968, RCA admitted its own responsibility in the production difficulties they were experiencing. Wayne Bledsoe, who had an impressive reputation in labor relations, took over as plant manager. The supervisory staff began attending sensitivity training seminars, and several foremen went, at company expense, on weekend retreats where they were drilled in handling personnel and individual counseling. At the same time, the Personnel Department took a greater voice in resolving labor disputes at the first line of management. These policy changes had a positive effect on production. In mid-1968, the Memphis plant finally began operating in the black and turning out sets at a faster rate than the older Indiana facilities.

A Bigger Picture

During RCA's tenure in Memphis, the tense social and political environment influenced plant operation. Prior to the opening, the city had escaped many of the racial confrontations experienced by other Deep South cities. Integration of parks, libraries and public accommodations had proceeded quietly without difficulties during the early 1960s. Voting rights had been extended to blacks by the Crump political machine as early as the 1930s. Thus the black community had been somewhat influential in local politics. For example, the black community had played a major role in electing a liberal mayor in 1963.4 This relative calm, however, gave way to racial tensions shortly after the RCA plant opened.

The black community grew increasingly impatient when the so-called liberal mayor elected in 1963 failed to improve the dismal black employment situation. Except for the new jobs produced through RCA, the economic picture for black workers had not been appreciably altered. The mayoral election of late 1967 further fueled the fires of discontent. By splitting the black vote, a white mayor was elected to office without any support from the black community.

The breaking point finally arrived in early 1968, when the city sanitation employees, who were mostly black, walked out on strike. The strike quickly became a focal point for the collective grievances of the black community against the new city leadership.^ And while unresponsive officials let the strike drag on for 65 days, the situation escalated into a major civil-rights conflict. Demonstrations and confrontations between young blacks and the police became almost a weekly occurrence. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in April, the focus of the national media turned to the city and stressed its negative aspects as "a decaying river town."

Relations within the RCA plant became more strained. Blacks were more militant in their stand against the company. They refused to settle issues without proceeding through the long, involved grievance process. Frequently, the disputes were over social injustices and not work rules spelled out in the contract. To gain greater power, blacks bloc-voted in union elections and elected more black local union officials and shop stewards who began successfully working through problems with RCA. By the beginning of 1969, both management and labor agreed that the production problems had been largely overcome. The plant was realizing a profit and production rates topped those in Bloomington.

Other factors, however, began to weigh against the plant's existence. Throughout the late '60s, the demand for color television failed to climb and in 1970 industry sales actually fell by $300 million. RCA profits peaked at $154 million in 1968 and began declining. The pressure from foreign producers was taking its toll on the domestic market.

In October, 1969, RCA announced the temporary layoff of 600 of its Memphis workers. In fact, it had no immediate plans to re-hire them. Wayne Bledsoe, plant manager, announced that only black and white sets would be produced in the future in Memphis as a part of the company's overall goal to "reduce inventories." But reducing the level of production in Memphis prevented the plant from operating in the black. In January, 1970, the company said the plant would begin making outdoor antennae for TVs and FM radios, but new products failed to help the situation.

By March, 1970, the combination of the recession and its loss of the television market share forced RCA to close down several plants, idling some 9,500 workers, including many in Memphis. Then one more crisis hit the company. The electrical workers' threeyear contract ended, and while the company outlook was bleak, workers had to contend with rising inflation. On June 3, 1970, the IUE went out on strike, rejecting a contract similar to the one recently accepted by the IBEW at 12 other RCA plants. The strike was long and difficult. When it finally ended in mid-August, only eight of the 12 IUE locals affected voted to accept the new contract.

On October 22, 1970, a local news paper ran the headline: "RCA Officials Recommend Closing Memphis Plant as Aftermath of Study." Tom Bradshaw, RCA public relations official, said the new labor contract had nothing to do with the study's recommendation. The corporate message read in part: "RCA has been studying ways to consolidate certain consumer production facilities in order to meet the rising costs of materials and manufacturing and to respond to increasingly competitive conditions in the industry." The decision called for closing the Memphis plant on December 9, 1970, and concentrating production in Indiana. The union, however, claimed that the plant was moving to Taiwan. Many Memphis citizens even insisted that equipment was put on a barge, sent down the Mississippi and from there shipped to Taiwan.

The Shut-Down

At the beginning of December, 1970, only about 1,200 workers remained on the payroll. After the large layoff during the previous summer, RCA had continued a series of small job terminations each month. On December 31, 1970, as the day shift left the facility, the RCA plant closed its production facilities in Memphis. Needless to say, the closing was a significant blow to the former employees.

Nearly 70 percent of them were heads of households, two-thirds were black, and many faced debts which they had taken on in more secure times. Because of the seniority rules, those who remained at the end had been those most committed to staying with the company, but the skills they had learned could not be transferred to other Memphis industries. They felt bitter toward the company for turning its back on American workers and toward the union for "going too far" in its demands in the 1970 contract. One former line operative spoke of her feelings about the closing:

"We all kinda knew for six months the plant was going to fold its operation here. There just weren't that many working anymore, the place was like a morgue. Morale was really low. When I got that final notice just before Christmas I was mad as hell. I had more bills then than when I had gone to work. Worst of all, I lost my hospitalization for my kids. All I could think, if I didn't find another job, we'd have to go back down to that City Hospital if anything happened.

"You ask me if I was bitter. Man, I can't tell you how I felt. I felt a lot worse when I tried to find another job. Who wanted a woman that could solder TV terminals? Nobody. The only thing available was a cook's helper in a nursing home paying less money than I got from unemployment."

The IUE, on behalf of its members and for its own defense, carried the case to the Federal Tariff Commission. Under the agreements in the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, the union charged the RCA management with shifting its production overseas without compensating US employees. RCA denied the charge, but the Tariff Commission ruled in favor of the union. Because of this, the government had to provide retraining benefits and extend unemployment compensation beyond the maximum time period.6 The union had made its point, but the plant was still closed. It remains empty today.7

RCA, like other major corporations that look for new industrial sites in the South, considered its profit statement more than the impact of its plant on working people. RCA was willing to deal with big unions, even to send its supervisory personnel to sensitivity training sessions. But when profits declined, product competition increased and a domestic recession ensued, RCA moved to protect its wealth by reducing the costs of production dramatically. Like other manufacturers, they found what they wanted in the cheaper labor of a Third World country. Other electronics plants were making the same decisions in 1970-71: Sarkes Tarzian closed its plants in Mississippi and Arkansas, laying off a thousand black workers, and moved to Mexico. Huge lay-offs at Warwick's plant in Forrest City, Ark., and Advance Ross Electronics in El Paso left hundreds of others unemployed. As in Memphis, the workers were simply sacrificed to the demands of a changing economy.

Ironically, rather than attack RCA's decision for the loss of local revenue and jobs it caused, Memphis leaders — unlike the corporation — blamed the workers for the plant's departure. The fluctuations of the television market were barely mentioned. Even six years after the closing, it is not uncommon to hear explanations that the employees were sloppy, lazy, lowskilled and poorly disciplined. In reality, they were as productive as most American workers and had successfully made the transition to industrial employment.

The degree of impact of these rumors can be measured by the fact that many employers refused to hire former RCA line operatives even after they had been retrained under federal programs. For several months after the closing, personnel at the state Department of Employment Security were told by employers not to send them any applicants who had worked for RCA. Workers who felt they had finally achieved mobility in the local labor market found themsleves branded as "troublemakers" or "prounion people.''

Most male hourly and salary workers eventually located new positions. However, employment at the plant had been dominated by women, and they had great difficulty finding other jobs. Most returned to a crowded secondary labor market, often to jobs similar to their pre-RCA ones. They had made a complete job cycle, and RCA had proven an agent of disruption rather than salvation. In addition, the departure of RCA meant the loss of desperately needed tax revenues for public services and improved facilities for human resource development.

The final result of the Memphis- RCA affair was not unique: the workers and their community were again victimized. Not by an individual boss. Not by a single company. The entire economic system had just moved along, trampling 4000 people in its wake.

FOOTNOTES

1. Moody's Industrial Manual: 1966,1970. New York: Moody's Investors Service, Inc., and Industrial Surveys; Electronics-Electrical: Basic Analysis. New York: Standard and Poor's, September 5, 1974.

2. The personal views presented in this article were collected over a three-month period from October through December, 1974. Interviews were obtained from 15 former RCA employees selected at random from various Divisions of the Memphis Plant (i.e., two salaried assembly line supervisors, one salaried official in labor relations, six hourly wage repairmen or "trouble shooters," six assembly line operatives). Interviews were also taken from two officials of the I.U.E. and three members of the Economic Development Division of Memphis Light, Gas and Water. All interviews were open-ended, averaging roughly one hour and 30 minutes. Each informant was assured anonymity. There were no refusals and all informants were cooperative.

3. Much of the information for this article was found in clippings from two Memphis newspapers, the Press Scimitar and the Commercial Appeal. An excellent file on the plant is maintained in the Memphis Room of the Memphis-Shelby County Public Library.

4. David M. Tucker, Memphis Since Crump (Memphis: Memphis State University, Ms.), p.38.

5. Thomas W. Collins, "An Analysis of the Memphis Garbage Strike," Public Affairs Forum, Vol. 3(6), p.4.

6. The computer output from the Tennessee Division of Employment Security and Final Report of Women and Girls Employment Enabling Service (prepared for U.S. Department of Labor under contract no. 88-47-72-02), indicates that 1,125 former RCA employees had signed up for special unemployment benefits as of February 1972. About 90 percent were women and 60-70 percent were black and had completed a high school education. During the next eighteen months about 300 completed job retraining programs. TDES data on 163 of these people gives an insight into the type of employment found by these workers. Forty-seven were trained to be cosmetologists; 29 gained employment in that area; Forty completed clerical programs; 23 had secretarial jobs thirty days later; and 29 out of 39 trained keypunch operators found jobs using their new skills. Of those who went back into production jobs as operatives, very few gained employment at unionized plants.

7. At one point, General Motors purchased the plant to produce recreational vehicles, but the energy crisis forced cancellation of those plans. Presently, Caterpillar plans to use the facility as a warehouse.

Tags

David Ciscel

David Ciscel and Tom Collins are assistant professors of economics and anthropology at Memphis State University. The research for this article was partially funded by a grant from the Center for Manpower Studies at MSU. (1976)

Tom Collins

David Ciscel and Tom Collins are assistant professors of economics and anthropology at Memphis State University. The research for this article was partially funded by a grant from the Center for Manpower Studies at MSU. (1976)